Multi-Cropping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D at a Kailash Nath Dikshit

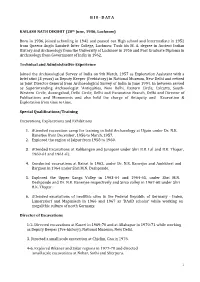

B I 0 - D AT A KAILASH NATH DIKSHIT (20th June, 1936, Lucknow) Born in 1936, joined schooling in 1942 and passed out High school and Intermediate in 1952 from Queens Anglo Sanskrit Inter College, Lucknow. Took his M. A. degree in Ancient Indian History and Archaeology from the University of Lucknow in 1956 and Post Graduate Diploma in Archaeology from Government of India in 1962. Technical and Administrative Experience Joined the Archaeological Survey of India on 9th March, 1957 as Exploration Assistant with a brief stint (3 years) as Deputy Keeper (Prehistory) in National Museum, New Delhi and retired as Joint Director General from Archaeological Survey of India in June 1994. In between served as Superintending Archaeologist 'Antiquities, New Delhi, Eastern Circle, Calcutta, South- Western Circle, Aurangabad, Delhi Circle, Delhi and Excavation Branch, Delhi and Director of Publications and Monuments and also held the charge of Antiquity and Excavation & Exploration from time to time. Special Qualifications/Training Excavations, Explorations and Exhibitions 1. Attended excavation camp for training in field Archaeology at Ujjain under Dr. N.R. Banerjee from December, 1956 to March, 1957. 2. Explored the region of Jaipur from 1958 to 1960. 3. Attended Excavations at Kalibangan and Junapani under Shri B.B. Lal and B.K. Thapar, 1960-61 and 1961-62. 4. Conducted excavations at Bairat in 1962, under Dr. N.R. Banerjee and Ambkheri and Bargaon in 1964 under Shri M.N. Deshpande. 5. Explored the Upper Ganga Valley in 1963-64 and 1964-65, under Shri M.N. Deshpande and Dr. N.R. Banerjee respectively and Sirsa valley in 1967-68 under Shri B.K. -

List of QCI Certified Professionals

List of QCI Certified Professionals S.No Name Yoga Level Address Mr Ankit Tiwari Level 2 - Yoga Teacher A-21, Type-2, Police Line, Roshanabad, Haridwar, 1 Uttarakhand-249403 Mr Amit Kashyap Level 2 - Yoga Teacher 2 29/1067, Baba Kharak Singh Marg, New Delhi-110001 Ms Aashima Malhotra Level 2 - Yoga Teacher 425, Aashirwad Enclave, Plot No. 104, I.P. Extn., Delhi- 3 110092 Mr Avinash Ghasi Level 2 - Yoga Teacher Address - C-73, Aishwaryam Apartment, Plot 17, 4 Sector-4, Dwarka, New Delhi. 110078 Mr Kiran Kumar Bhukya Level 2 - Yoga Teacher H.No. 494 Chandya b Tanda Thattpalle Kuravi - 5 Warangal,-506105 6 Ms Komal Kedia Level 2 - Yoga Teacher FG-1/92B, Vikaspuri, LIG Flats, New Delhi-110018 7 Ms Neetu Level 2 - Yoga Teacher C-64-65, Kewal Park, Azadpur, Delhi-110033 Mr Pardeep Bhardwaj Level 2 - Yoga Teacher H.No. 160, Shri Shyam Baba Chowk, VPO Khera 8 Khurd, Delhi-110082 Mr Pushp Dant Level 2 - Yoga Teacher 77, Sadbhavana Apartments, Plot 13, IP Extension, 9 Delhi - 110092 Mr S.uday Kumar Level 2 - Yoga Teacher H.No. 20-134/11, Teacher's Colony, Achampet Distt., 10 Mahabubnagar, Telangana-509375 11 Mr Saurabh Grover Level 2 - Yoga Teacher C-589, Street No. 3, Ganesh Nagar-II, Delhi-110092 Ms Smita Kumari Level 2 - Yoga Teacher B-Type, Q. No. 17, Sector-3, M.O.C.P. Colony, 12 Alakdiha, P.O. Pargha Jharia, Dhanbad, Jharkhand- 82820 13 Ms Tania Level 2 - Yoga Teacher E-296, MCD Colony, Azadpur, Delhi-110033 Ms Veenu Soni Level 2 - Yoga Teacher X/3543, St. -

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT EBSTRACT As pointed out by N. G. Majumdar in 1934, a late phase of lndus civilization is illustrated by pottery discovered at the upper levels of Jhukar and Mohenjo-daro. However, it was the excavation at Rangpur which revealed in stratification a general decline in the prosperity of the Harappan culture. The cultural gamut of the nuclear region of the lndus-Sarasvati divide, when compared internally, revealed regional variations conforming to devolutionary tendencies especially in the peripheral region of north and western lndia. A large number of sites, now loosely termed as 'Late Harappan/Post-urban', have been discovered. These sites, which formed the disrupted terminal phases of the culture, lost their status as Harappan. They no doubt yielded distinctive Harappan pottery, antiquities and remnants of some architectural forms, but neither town planning nor any economic and cultural nucleus. The script also disappeared. ln this paper, an attempt is made with the survey of some of these excavated sites and other exploratory field-data noticed in the lndo-Pak subcontinent, to understand the complex issue.of Harappan decline and its legacy. CONTENTS l.INTRODUCTION 2. FIELD DATA A. Punjab i. Ropar ii. Bara iii. Dher Majra iv. Sanghol v. Katpalon vi. Nagar vii. Dadheri viii. Rohira B. Jammu and Kashmir i. Manda C. Haryana i. Mitathal ii. Daulatpur iii. Bhagwanpura iv. Mirzapur v. Karsola vi. Muhammad Nagar D. Delhi i. Bhorgarh 125 ANCiENT INDlA,NEW SERIES,NO.1 E.Western Uttar Pradesh i.Hulas il.Alamgirpur ili.Bargaon iv.Mandi v Arnbkheri v:.Bahadarabad F.Guiarat i.Rangpur †|.Desalpur ili.Dhola宙 ra iv Kanmer v.」 uni Kuran vi.Ratanpura G.Maharashtra i.Daimabad 3.EV:DENCE OF RICE 4.BURIAL PRACTiCES 5.DiSCUSS10N 6.CLASSiFiCAT10N AND CHRONOLOGY 7.DATA FROM PAKISTAN 8.BACTRIA―MARGIANAARCHAEOLOGICAL COMPLEX AND LATE HARAPPANS 9.THE LEGACY 10.CONCLUS10N ・ I. -

Oilseeds, Spices, Fruits and Flavour in the Indus Civilisation T J

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 24 (2019) 879–887 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Oilseeds, spices, fruits and flavour in the Indus Civilisation T J. Bates Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University, United States of America ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The exploitation of plant resources was an important part of the economic and social strategies of the people of South Asia the Indus Civilisation (c. 3200–1500 BCE). Research has focused mainly on staples such as cereals and pulses, for Prehistoric agriculture understanding these strategies with regards to agricultural systems and reconstructions of diet, with some re- Archaeobotany ference to ‘weeds’ for crop processing models. Other plants that appear less frequently in the archaeobotanical Indus Civilisation record have often received variable degrees of attention and interpretation. This paper reviews the primary Cropping strategies literature and comments on the frequency with which non-staple food plants appear at Indus sites. It argues that Food this provides an avenue for Indus archaeobotany to continue its ongoing development of models that move beyond agriculture and diet to think about how people considered these plants as part of their daily life, with caveats regarding taphonomy and culturally-contextual notions of function. 1. Introduction 2. Traditions in Indus archaeobotany By 2500 BCE the largest Old World Bronze Age civilisation had There is a long tradition of Indus archaeobotany. As summarised in spread across nearly 1 million km2 in what is now Pakistan and north- Fuller (2002) it can be divided into three phases: ‘consulting palaeo- west India (Fig. -

Download Book

EXCAVATIONS AT RAKHIGARHI [1997-98 to 1999-2000] Dr. Amarendra Nath Archaeological Survey of India 1 DR. AMARENDRA NATH RAKHIGARHI EXCAVATION Former Director (Archaeology) ASI Report Writing Unit O/o Superintending Archaeologist ASI, Excavation Branch-II, Purana Qila, New Delhi, 110001 Dear Dr. Tewari, Date: 31.12.2014 Please refer to your D.O. No. 24/1/2014-EE Dated 5th June, 2014 regarding report writing on the excavations at Rakhigarhi. As desired, I am enclosing a draft report on the excavations at Rakhigarhi drawn on the lines of the “Wheeler Committee Report-1965”. The report highlights the facts of excavations, its objective, the site and its environment, site catchment analysis, cultural stratigraphy, structural remains, burials, graffiti, ceramics, terracotta, copper, other finds with two appendices. I am aware of the fact that the report under submission is incomplete in its presentation in terms modern inputs required in an archaeological report. You may be aware of the fact that the ground staff available to this section is too meagre to cope up the work of report writing. The services of only one semiskilled casual labour engaged to this section has been withdrawn vide F. No. 9/66/2014-15/EB-II496 Dated 01.12.2014. The Assistant Archaeologist who is holding the charge antiquities and records of Rakhigarhi is available only when he is free from his office duty in the Branch. The services of a darftsman accorded to this unit are hardly available. Under the circumstances it is requested to restore the services of one semiskilled casual labour earlier attached to this unit and draftsman of the Excavation Branch II Purana Quila so as to enable the unit to function smoothly with limited hands and achieve the target. -

Immigrant Identity in the Indus Civilization: a Multi-Site Isotopic Mortuary Analysis

IMMIGRANT IDENTITY IN THE INDUS CIVILIZATION: A MULTI-SITE ISOTOPIC MORTUARY ANALYSIS By BENJAMIN THOMAS VALENTINE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Benjamin Thomas Valentine 2 To Shannon 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Truly, I have stood on the shoulders of my betters to reach this point in my career. I could never have completed this dissertation without the unfailing support of my family, friends, and colleagues, both at home and abroad. I am grateful, most of all, for my wife, Shannon Chillingworth. I am humbled by the sacrifices she has made for dreams not her own. I can never repay her for the gifts she has given me, nor will she ever call my debt due. Shannon—thank you. I am likewise indebted to the scholars and institutions that have facilitated my graduate research these past eight years. Foremost among them is my faculty advisor, John Krigbaum, who took a chance on me, an aspiring researcher with little anthropological training, and welcomed me into the University of Florida (UF) Bone Chemistry Lab. I have worked hard not to fail him, as he has never failed me. Under John Krigbaum’s mentorship, I have earned my chance to succeed in academe. During my time at UF, I have benefited from the efforts of many excellent faculty members, but I am especially grateful to James Davidson, Department of Anthropology and George Kamenov and Jason Curtis, Department of Geological Sciences. -

History of Saharanpur: an Overview the Physical Features of The

History Of Saharanpur: An Overview by traveldesk The physical features of the district have proved that Saharanpur region was fit for human habitation. The archaeological survey has proved that the evidence of different cultures is available in this area. The excavations were carried out in different parts of the district, i.e Ambakheri,Bargaon,Hulas,Bhadarabad and Naseerpur etc. A number of things have been found during these excavations, on the basis of which, it is established that in Saharanpur district, the earliest habitants were found as early as 2000B.C. Traces of Indus Valley civilization and even earlier are available and now it can be definitely established that this region is connected with Indus valley civilization. Ambakheri, Bargaon, Naseerpur and Hulas were the centres of Harappa culture because many things similar to Harappan civilization were found in these areas From the days of the Aryans, the history of this region is traceable in a logical manner but it is difficult at present to trace out history and administration of the local kings without further exploration and excavations.The history of the area goes back to ages. With the passage of timeit’s name changed rapidly. During the region of Iltutmish Saharanpur became a part of the Slave Dynasty. Muhammad Tughlag reached northern doab to crush the rebellion of Shiwalik Kings in 1340. There he came to know about the presence of a Sufi saint on the banks of 'Paondhoi' river. He went to see him there and ordered that henceforth the place should be known as 'Shah-Harunpur' by the name of Saint Shah Harun Chisti. -

Bārā Culture: an Overview of Problems and Issues

International Journal of Research e-ISSN: 2348-6848 p-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 05 Issue 12 April 2018 Bārā Culture: An Overview of Problems and Issues Sukhdev Saini Abstract: Bārā culture was a culture that emerged in the eastern region of the Indus Valley Civilization around 2000 BC. It developed in the doab between the Yamunā and Sutlej rivers, this territory corresponds to modern-day Punjab, Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh in North India. Bārā culture is believed to have initially developed from Pre-Harappan traditions independently, although later on intermingled with the Harappans in locations. In the conventional timeline demarcations of the Indus Valley Tradition, the Bārā culture is usually placed in the Late Harappan period. The Bārān pottery is thickly distributed in the Sutlej and Ghaghara basins. From this hub centre of the culture it has spread on the Sarasvatī and Driśdvatī in Haryana and to the Yamunā-Gangā doab in western Uttar Pradesh. The painted designs of Bārān ware recall the Pre-Harappan designs from north Baluchistan, Bahawalpur, Sind and Ganganagar areas. So, this poses a problem among the archaeologists regarding the origin and expansion of this culture. Bārān ware plausibly is a local version or variable of 'Pre-Indus pottery', perhaps a near cognate of pre-defence Harappan ware which shows many traits with these various contemporary Chalcolithic cultures. In the Chautāng valley Bārān ware is largely comparable to Siswālian ware. Bārā- Siswālian ware is a long-lived ceramic with Early Harappan motifs carrying the entire sequence in Divide. So, it is called Bārā-Siswālian pottery tradition. -

Indian Archaeology 1980-81 a Review

INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY 1980-81 —A REVIEW EDITED BY DEBALA MITTRA Director General Archaeological Survey of India ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI 1983 Cover : rock-paintings, Bhimbetka 1983 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Prices : Rs. 65.00 PRINTED AT NABA MUDRAN PRIVATE LIMITED, CALCUTTA, 700004 PREFACE This is the twenty-eighth issue of the Review containing report on archaeological activities in various fields including certain spheres of interdisciplinary researches. Thanks to the Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmadabad, and the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Bombay, we have now been able to introduce a sub-section on the thermoluminescence dating. I hope these institutions along with the Birbal Sahani Institute of Palaeobotany, Lucknow, will continue to devote their time and attention to the cause of archaeological research in India. It is a matter of great satisfaction that the Deccan College Post-graduate and Research Institute, Pune, has stepped forward for undertaking multidisciplinary archaeological investigations. The manuscript for the Review for 1981-82 will shortly be sent to the press; it is hoped that the issue will be printed off by the end of this year. Much of the time in compilation can be saved if all the contributors follow the pattern systematized in the Review and use the spelling of place-names as given in the maps of Survey of India. Apart from the items relating to the activities of Archaeological Survey which have been supplied by my colleagues in Headquarters, Circles and Branches, the material was received as usual from various State Governments, Universities and other research organizations. -

Plant Domestication in Indus Valley Civilisation

IJHS | VOL 55.4 | DECEMBER 2020 HISTORICAL NOTES Plant Domestication in Indus Valley Civilisation R. B. Mohantya, T. Pandab,∗ a Ex-Reader in Botany, Satya Bihar, Rasulgarh, Bhubaneswar. b Department of Botany, Chandbali College, Chandbali. (Received 07 April 2019; revised 01 October 2020) Abstract The paper tries to document about 54 plant species including cereal, millets, pulses, vegetables, medicines and some other economically important species of Indus Valley civilization. The plant species discovered during the archaeo-botanical excavations not only indicate the food habit of the people inhabiting the region but also help in biological reconstruction of the past environment, ecological systems and the climatic changes that took place during the period. Key words: Archaeo-botanical excavations, Harappan civilization, Mohenjo-daro. 1 Introduction The early Harappan community had turned into large urban centers by 2600 BCE with well-developed town Indus Valley was a Bronze Age civilization extending planning, water supply and drainage system, impressive from north-east Afghanistan to Pakistan and north-west dock yards, granaries, warehouses, brick platforms and India. It is also known as Harappan civilization (McIn- protective walls. Indus civilization at its peak (2600–1900 tosh 2008; Shinde et al. 2019) which thrived from 3200 BCE) had a population of about four to six million peo- to 1900 BCE (Possehl 1992; Lal 1997; Madella and Fuller ple (Desai 2019) and Mohenjo-daro was the greatest city 2006; Agarwal 2007; Kenoyer 2008; Weber et al. 2010; in the world with around 40,000 inhabitants (Mcintosh Pokharia et al. 2014). First excavated in 1921, over 1500 2008; Nipper 2018). -

Killing the Priest-King: Addressing Egalitarianism in the Indus Civilization

Journal of Archaeological Research https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-020-09147-9 Killing the Priest‑King: Addressing Egalitarianism in the Indus Civilization Adam S. Green1 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The cities of the Indus civilization were expansive and planned with large-scale architecture and sophisticated Bronze Age technologies. Despite these hallmarks of social complexity, the Indus lacks clear evidence for elaborate tombs, individual- aggrandizing monuments, large temples, and palaces. Its frst excavators suggested that the Indus civilization was far more egalitarian than other early complex soci- eties, and after nearly a century of investigation, clear evidence for a ruling class of managerial elites has yet to materialize. The conspicuous lack of political and economic inequality noted by Mohenjo-daro’s initial excavators was basically cor- rect. This is not because the Indus civilization was not a complex society, rather, it is because there are common assumptions about distributions of wealth, hierarchies of power, specialization, and urbanism in the past that are simply incorrect. The Indus civilization reveals that a ruling class is not a prerequisite for social complexity. Keywords Inequality · Indus civilization · Urbanization · Class · Stratifcation · Collective action · Heterarchy Introduction ….there is nothing that we know of in prehistoric Egypt or Mesopotamia or anywhere else in Western Asia to compare with the well-built baths and com- modious houses of the citizens of Mohenjo-daro. In those countries, much money and thought were lavished on the building of magnifcent temples for the gods and on palaces and tombs of kings, but the rest of the people seem- ingly had to content themselves with insignifcant dwellings of mud. -

The Indus Valley Tradition of Pakistan and Western India

Journal of Worm Prehistory, Vol. 5, No. 4, 1991 The Indus Valley Tradition of Pakistan and Western India Jonathan Mark Kenoyer ~ Over the last several decades new sets of information have provided a more detailed understanding of the rise and character of the Indus Civilization as well as its decline and decentralization. This article begins with a summary of the major historical developments in the archaeology of the Indus Valley Tra- dition and a definition of terms found in the literature. A general discussion of the environmental setting and certain preconditions for the rise of urban and state-level society is followed by a summary of the major aspects of the Har- appan Phase of the Indus Valley Tradition. This summary includes discussions of settlement patterns, subsistence, architecture, trade and exchange, special- ized crafts, language, religion, and social organization. The Localization Era or decentralization of the urban centers is also addressed. KEY WORDS: Indus Valley Tradition; Integration Era; Harappan Phase; subsistence; trade; spe- cialized crafts; urbanism; belief systems; state-level organization. INTRODUCTION South Asia's earliest urban society has been the focus of scholarly debate since its discovery in the 1920s (Chakrabarti, 1984; Jacobson, 1987). Early interpretations were based primarily on data from the major urban centers. A more balanced perspective has been achieved through excavations at both urban and rural settlements in Pakistan and in western India and adjacent regions and recent studies of previously excavated materials (Bisht, 1982, 1989, 1990; Dales and Kenoyer, 1990b; Jansen and Urban, 1984, 1987; Jarrige, 1986; Mughal, 1982, 1984; Possehl and Raval, 1989).