The Published Archaeobotanical Data from the Indus Civilisation, South Asia, C.3200–1500BC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

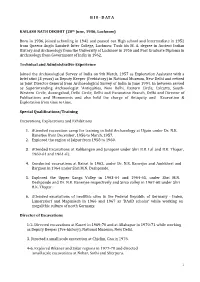

D at a Kailash Nath Dikshit

B I 0 - D AT A KAILASH NATH DIKSHIT (20th June, 1936, Lucknow) Born in 1936, joined schooling in 1942 and passed out High school and Intermediate in 1952 from Queens Anglo Sanskrit Inter College, Lucknow. Took his M. A. degree in Ancient Indian History and Archaeology from the University of Lucknow in 1956 and Post Graduate Diploma in Archaeology from Government of India in 1962. Technical and Administrative Experience Joined the Archaeological Survey of India on 9th March, 1957 as Exploration Assistant with a brief stint (3 years) as Deputy Keeper (Prehistory) in National Museum, New Delhi and retired as Joint Director General from Archaeological Survey of India in June 1994. In between served as Superintending Archaeologist 'Antiquities, New Delhi, Eastern Circle, Calcutta, South- Western Circle, Aurangabad, Delhi Circle, Delhi and Excavation Branch, Delhi and Director of Publications and Monuments and also held the charge of Antiquity and Excavation & Exploration from time to time. Special Qualifications/Training Excavations, Explorations and Exhibitions 1. Attended excavation camp for training in field Archaeology at Ujjain under Dr. N.R. Banerjee from December, 1956 to March, 1957. 2. Explored the region of Jaipur from 1958 to 1960. 3. Attended Excavations at Kalibangan and Junapani under Shri B.B. Lal and B.K. Thapar, 1960-61 and 1961-62. 4. Conducted excavations at Bairat in 1962, under Dr. N.R. Banerjee and Ambkheri and Bargaon in 1964 under Shri M.N. Deshpande. 5. Explored the Upper Ganga Valley in 1963-64 and 1964-65, under Shri M.N. Deshpande and Dr. N.R. Banerjee respectively and Sirsa valley in 1967-68 under Shri B.K. -

A Gis Tool to Demonstrate Ancient Harappan

A GIS TOOL TO DEMONSTRATE ANCIENT HARAPPAN CIVILIZATION _______________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of San Diego State University _______________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Computer Science _______________ by Kesav Srinath Surapaneni Summer 2011 iii Copyright © 2011 by Kesav Srinath Surapaneni All Rights Reserved iv DEDICATION To my father Vijaya Nageswara rao Surapaneni, my mother Padmaja Surapaneni, and my family and friends who have always given me endless support and love. v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS A GIS Tool to Demonstrate Ancient Harappan Civilization by Kesav Srinath Surapaneni Master of Science in Computer Science San Diego State University, 2011 The thesis focuses on the Harappan civilization and provides a better way to visualize the corresponding data on the map using the hotlink tool. This tool is made with the help of MOJO (Map Objects Java Objects) provided by ESRI. The MOJO coding to read in the data from CSV file, make a layer out of it, and create a new shape file is done. A suitable special marker symbol is used to show the locations that were found on a base map of India. A dot represents Harappan civilization links from where a user can navigate to corresponding web pages in response to a standard mouse click event. This thesis also discusses topics related to Indus valley civilization like its importance, occupations, society, religion and decline. This approach presents an effective learning tool for students by providing an interactive environment through features such as menus, help, map and tools like zoom in, zoom out, etc. -

List of QCI Certified Professionals

List of QCI Certified Professionals S.No Name Yoga Level Address Mr Ankit Tiwari Level 2 - Yoga Teacher A-21, Type-2, Police Line, Roshanabad, Haridwar, 1 Uttarakhand-249403 Mr Amit Kashyap Level 2 - Yoga Teacher 2 29/1067, Baba Kharak Singh Marg, New Delhi-110001 Ms Aashima Malhotra Level 2 - Yoga Teacher 425, Aashirwad Enclave, Plot No. 104, I.P. Extn., Delhi- 3 110092 Mr Avinash Ghasi Level 2 - Yoga Teacher Address - C-73, Aishwaryam Apartment, Plot 17, 4 Sector-4, Dwarka, New Delhi. 110078 Mr Kiran Kumar Bhukya Level 2 - Yoga Teacher H.No. 494 Chandya b Tanda Thattpalle Kuravi - 5 Warangal,-506105 6 Ms Komal Kedia Level 2 - Yoga Teacher FG-1/92B, Vikaspuri, LIG Flats, New Delhi-110018 7 Ms Neetu Level 2 - Yoga Teacher C-64-65, Kewal Park, Azadpur, Delhi-110033 Mr Pardeep Bhardwaj Level 2 - Yoga Teacher H.No. 160, Shri Shyam Baba Chowk, VPO Khera 8 Khurd, Delhi-110082 Mr Pushp Dant Level 2 - Yoga Teacher 77, Sadbhavana Apartments, Plot 13, IP Extension, 9 Delhi - 110092 Mr S.uday Kumar Level 2 - Yoga Teacher H.No. 20-134/11, Teacher's Colony, Achampet Distt., 10 Mahabubnagar, Telangana-509375 11 Mr Saurabh Grover Level 2 - Yoga Teacher C-589, Street No. 3, Ganesh Nagar-II, Delhi-110092 Ms Smita Kumari Level 2 - Yoga Teacher B-Type, Q. No. 17, Sector-3, M.O.C.P. Colony, 12 Alakdiha, P.O. Pargha Jharia, Dhanbad, Jharkhand- 82820 13 Ms Tania Level 2 - Yoga Teacher E-296, MCD Colony, Azadpur, Delhi-110033 Ms Veenu Soni Level 2 - Yoga Teacher X/3543, St. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: Page numbers in italics refer to figures and tables. 16R dune site, 36, 43, 440 Adittanallur, 484 Adivasi peoples see tribal peoples Abhaipur, 498 Adiyaman dynasty, 317 Achaemenid Empire, 278, 279 Afghanistan Acharyya, S.K., 81 in “Aryan invasion” hypothesis, 205 Acheulean industry see also Paleolithic era in history of agriculture, 128, 346 in Bangladesh, 406, 408 in human dispersals, 64 dating of, 33, 35, 38, 63 in isotope analysis of Harappan earliest discovery of, 72 migrants, 196 handaxes, 63, 72, 414, 441 skeletal remains found near, 483 in the Hunsgi and Baichbal valleys, 441–443 as source of raw materials, 132, 134 lack of evidence in northeastern India for, 45 Africa major sites of, 42, 62–63 cultigens from, 179, 347, 362–363, 370 in Nepal, 414 COPYRIGHTEDhominoid MATERIAL migrations to and from, 23, 24 in Pakistan, 415 Horn of, 65 related hominin finds, 73, 81, 82 human migrations from, 51–52 scholarship on, 43, 441 museums in, 471 Adam, 302, 334, 498 Paleolithic tools in, 40, 43 Adamgarh, 90, 101 research on stature in, 103 Addanki, 498 subsistence economies in, 348, 353 Adi Badri, 498 Agara Orathur, 498 Adichchanallur, 317, 498 Agartala, 407 Adilabad, 455 Agni Purana, 320 A Companion to South Asia in the Past, First Edition. Edited by Gwen Robbins Schug and Subhash R. Walimbe. © 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2016 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 0002649130.indd 534 2/17/2016 3:57:33 PM INDEX 535 Agra, 337 Ammapur, 414 agriculture see also millet; rice; sedentism; water Amreli district, 247, 325 management Amri, -

Model Test Paper-1

MODEL TEST PAPER-1 No. of Questions: 120 Time: 2 hours Codes: I II III IV (a) A B C D Instructions: (b) C A B D (c) A C D B (A) All questions carry equal marks (d) C A D B (B) Do not waste your time on any particular question 4. Where do we find the three phases, viz. Paleolithic, (C) Mark your answer clearly and if you want to change Mesolithic and Neolithic Cultures in sequence? your answer, erase your previous answer completely. (a) Kashmir Valley (b) Godavari Valley (c) Belan Valley (d) Krishna Valley 1. Pot-making, a technique of great significance 5. Excellent cave paintings of Mesolithic Age are found in human history, appeared first in a few areas at: during: (a) Bhimbetka (b) Atranjikhera (a) Early Stone Age (b) Middle Stone Age (c) Mahisadal (d) Barudih (c) Upper Stone Age (d) Late Stone Age 6. In the upper Ganga valley iron is first found associated 2. Which one of the following pairs of Palaeolithic sites with and areas is not correct? (a) Black-and-Red Ware (a) Didwana—Western Rajasthan (b) Ochre Coloured Ware (b) Sanganakallu—Karnataka (c) Painted Grey Ware (c) Uttarabaini—Jammu (d) Northern Black Polished Ware (d) Riwat—Pakistani Punjab 7. Teri sites, associated with dunes of reddened sand, 3. Match List I with List II and select the answer from are found in: the codes given below the lists: (a) Assam (b) Madhya Pradesh List I List II (c) Tamil Nadu (d) Andhra Pradesh Chalcolithic Cultures Type Sites 8. -

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT EBSTRACT As pointed out by N. G. Majumdar in 1934, a late phase of lndus civilization is illustrated by pottery discovered at the upper levels of Jhukar and Mohenjo-daro. However, it was the excavation at Rangpur which revealed in stratification a general decline in the prosperity of the Harappan culture. The cultural gamut of the nuclear region of the lndus-Sarasvati divide, when compared internally, revealed regional variations conforming to devolutionary tendencies especially in the peripheral region of north and western lndia. A large number of sites, now loosely termed as 'Late Harappan/Post-urban', have been discovered. These sites, which formed the disrupted terminal phases of the culture, lost their status as Harappan. They no doubt yielded distinctive Harappan pottery, antiquities and remnants of some architectural forms, but neither town planning nor any economic and cultural nucleus. The script also disappeared. ln this paper, an attempt is made with the survey of some of these excavated sites and other exploratory field-data noticed in the lndo-Pak subcontinent, to understand the complex issue.of Harappan decline and its legacy. CONTENTS l.INTRODUCTION 2. FIELD DATA A. Punjab i. Ropar ii. Bara iii. Dher Majra iv. Sanghol v. Katpalon vi. Nagar vii. Dadheri viii. Rohira B. Jammu and Kashmir i. Manda C. Haryana i. Mitathal ii. Daulatpur iii. Bhagwanpura iv. Mirzapur v. Karsola vi. Muhammad Nagar D. Delhi i. Bhorgarh 125 ANCiENT INDlA,NEW SERIES,NO.1 E.Western Uttar Pradesh i.Hulas il.Alamgirpur ili.Bargaon iv.Mandi v Arnbkheri v:.Bahadarabad F.Guiarat i.Rangpur †|.Desalpur ili.Dhola宙 ra iv Kanmer v.」 uni Kuran vi.Ratanpura G.Maharashtra i.Daimabad 3.EV:DENCE OF RICE 4.BURIAL PRACTiCES 5.DiSCUSS10N 6.CLASSiFiCAT10N AND CHRONOLOGY 7.DATA FROM PAKISTAN 8.BACTRIA―MARGIANAARCHAEOLOGICAL COMPLEX AND LATE HARAPPANS 9.THE LEGACY 10.CONCLUS10N ・ I. -

Kenoyer2004 Wheeled Vehicles of the Indus Valley Civilization.Pdf

1 Kenoyer, J. M. 2004 Die KalTen der InduskuItur Pakistans und Indiens (Wheeled Vehicles oftbe Indus Valley Civilization of Pakistan and India). In Bad unil Wagen: Der Ursprung einer Innovation Wagen im Vorderen Orient und Europa (Wheel and Wagon - origins ofan innovation), edited by M" Fansa and S. Burmeister, pp. 87-106. Mainz am Rhein, Verlagg Philipp von Zabem. Wheeled Vehicles of the Indus Valley Civilization of Pakistan and India. By Jonathan Mark Kenoyer University of Wisconsin- Madison Jan 7,2004 Introduction The Indus valley of northwestern South Asia has long been known as an important center for the emergence of cities and urban society during the mid third millennium Be. However, it is only in the last two decades that new and more detailed scientific excavations and analysis have begun to reveal the complex processes through which these urban centers emerged (Kenoyer 1998, 2003, Posseh12002). In this paper I will focus on the early use and gradual development of wheeled vehicles at the site of Harappa, Pakistan, in order to better understand the role of carts in this process of urban development. The earliest Neolithic communities that emerged along the edges of the Indus VaIley around 7000 Be do not reveal the use of wheeled vehicles Oarrige et al. 1995; Jarrige and Meadow 1980), but as sedentary farming communities became established out in the alluvial plain of the Indus river and its tributaries (Figure 1), more effective means of transporting heavy raw material would have been a major concern. In the alluvial plains that make up the core area of the later Indus civilization no rock is available exceptin the region around the Rohri Hills, Sindh. -

Oilseeds, Spices, Fruits and Flavour in the Indus Civilisation T J

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 24 (2019) 879–887 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Oilseeds, spices, fruits and flavour in the Indus Civilisation T J. Bates Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University, United States of America ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The exploitation of plant resources was an important part of the economic and social strategies of the people of South Asia the Indus Civilisation (c. 3200–1500 BCE). Research has focused mainly on staples such as cereals and pulses, for Prehistoric agriculture understanding these strategies with regards to agricultural systems and reconstructions of diet, with some re- Archaeobotany ference to ‘weeds’ for crop processing models. Other plants that appear less frequently in the archaeobotanical Indus Civilisation record have often received variable degrees of attention and interpretation. This paper reviews the primary Cropping strategies literature and comments on the frequency with which non-staple food plants appear at Indus sites. It argues that Food this provides an avenue for Indus archaeobotany to continue its ongoing development of models that move beyond agriculture and diet to think about how people considered these plants as part of their daily life, with caveats regarding taphonomy and culturally-contextual notions of function. 1. Introduction 2. Traditions in Indus archaeobotany By 2500 BCE the largest Old World Bronze Age civilisation had There is a long tradition of Indus archaeobotany. As summarised in spread across nearly 1 million km2 in what is now Pakistan and north- Fuller (2002) it can be divided into three phases: ‘consulting palaeo- west India (Fig. -

South Asian Archaeology 2012

South Asian Archaeology 2012 21st EASAA Conference / 21ème colloque de l’EASAA Paris, 2nd-6th July 2012 / 2-6 juillet 2012 Ecole du Louvre Organisation Avec le soutien de / with the support of et du / and of Transporteur officiel / Offical carrier President Dr. Vincent Lefèvre Comité d’organisation / Organisation committee Vincent Lefèvre, Bérénice Bellina-Pryce, Sophie Mouquin Comité de selection / Bérénice Bellina-Pryce, Laurianne Bruneau, Aurore Didier, Vincent Lefèvre, Edith Parlier-Renault, Amina Taha Hussein Okada South Asian Archaeology 2012 - Abstracts Nota: the following abstracts are reproduced in the form in which they have been submitted by the participants; no editiing work has been undertaken and we are not responsible for any inconsistencies in the spelling of proper nouns. Keynote lecture: Jean-François Jarrige Indus-Oxus Civilisations: More Thoughts Some thirty years ago excavations in the north-west of Afghanistan, in Tadjikistan and Uzbekistan (Bactria) and later on in Turkmenistan (Margiana) revealed the existence of a so far unknown extensive original cultural complex whose climax could be dated around 2100/1900 BC. Since then excavations of major sites such as Gonur, Togolok or Sappali Tepe have contributed to show the obvious economical dynamism and the great wealth what has been termed by some specialists as the Bactria-Margina Archaeological Complex (BMAC) or by others as the Oxus civilisation. So, some of the few “exotic” objects found at several sites of the Indus civilisation, could be then related to this “Oxus” civilisation and no longer to rather poorly known invaders in the context of what was assumed to be the collapsing process of the Indus cities. -

Download Book

EXCAVATIONS AT RAKHIGARHI [1997-98 to 1999-2000] Dr. Amarendra Nath Archaeological Survey of India 1 DR. AMARENDRA NATH RAKHIGARHI EXCAVATION Former Director (Archaeology) ASI Report Writing Unit O/o Superintending Archaeologist ASI, Excavation Branch-II, Purana Qila, New Delhi, 110001 Dear Dr. Tewari, Date: 31.12.2014 Please refer to your D.O. No. 24/1/2014-EE Dated 5th June, 2014 regarding report writing on the excavations at Rakhigarhi. As desired, I am enclosing a draft report on the excavations at Rakhigarhi drawn on the lines of the “Wheeler Committee Report-1965”. The report highlights the facts of excavations, its objective, the site and its environment, site catchment analysis, cultural stratigraphy, structural remains, burials, graffiti, ceramics, terracotta, copper, other finds with two appendices. I am aware of the fact that the report under submission is incomplete in its presentation in terms modern inputs required in an archaeological report. You may be aware of the fact that the ground staff available to this section is too meagre to cope up the work of report writing. The services of only one semiskilled casual labour engaged to this section has been withdrawn vide F. No. 9/66/2014-15/EB-II496 Dated 01.12.2014. The Assistant Archaeologist who is holding the charge antiquities and records of Rakhigarhi is available only when he is free from his office duty in the Branch. The services of a darftsman accorded to this unit are hardly available. Under the circumstances it is requested to restore the services of one semiskilled casual labour earlier attached to this unit and draftsman of the Excavation Branch II Purana Quila so as to enable the unit to function smoothly with limited hands and achieve the target. -

Immigrant Identity in the Indus Civilization: a Multi-Site Isotopic Mortuary Analysis

IMMIGRANT IDENTITY IN THE INDUS CIVILIZATION: A MULTI-SITE ISOTOPIC MORTUARY ANALYSIS By BENJAMIN THOMAS VALENTINE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Benjamin Thomas Valentine 2 To Shannon 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Truly, I have stood on the shoulders of my betters to reach this point in my career. I could never have completed this dissertation without the unfailing support of my family, friends, and colleagues, both at home and abroad. I am grateful, most of all, for my wife, Shannon Chillingworth. I am humbled by the sacrifices she has made for dreams not her own. I can never repay her for the gifts she has given me, nor will she ever call my debt due. Shannon—thank you. I am likewise indebted to the scholars and institutions that have facilitated my graduate research these past eight years. Foremost among them is my faculty advisor, John Krigbaum, who took a chance on me, an aspiring researcher with little anthropological training, and welcomed me into the University of Florida (UF) Bone Chemistry Lab. I have worked hard not to fail him, as he has never failed me. Under John Krigbaum’s mentorship, I have earned my chance to succeed in academe. During my time at UF, I have benefited from the efforts of many excellent faculty members, but I am especially grateful to James Davidson, Department of Anthropology and George Kamenov and Jason Curtis, Department of Geological Sciences. -

Royal “Chariot” Burials of Sanauli Near Delhi and Archaeological Correlates of Prehistoric Indo-Iranian Languages

ROYAL “CHARIOT” BURIALS OF SANAULI NEAR DELHI AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL CORRELATES OF PREHISTORIC INDO-IRANIAN LANGUAGES Asko Parpola University of Helsinki The article describes the royal cart burials excavated at the Late Harappan site of Sanauli near Delhi in the spring of 2018 on the basis of the available reports and photographs. The author then comments on these finds, dated to about 1900 BCE, with the Sanauli cart burials being the first of their kind in Bronze Age India. In his opinion, several indications suggest that the Sanauli “chariots” are actually carts yoked to bulls, as in the copper sculpture of a bull-cart from the Late Harappan site of Daimabad in Maharashtra. The antennae-hilted swords associated with the burials suggest that these bull-carts are likely to have come from the BMAC or the Bactria and Margiana Archaeological Complex (c.2300–1500 BCE) of southern Central Asia, from where there is iconographic evidence of bull-carts. The ultimate source of the Sanauli/BMAC bull-carts may be the early phase of the Sintashta culture in the Trans-Urals, where the chariot (defined as a horse-drawn light vehicle with two spoked wheels) was most probably invented around the late twenty-first century BCE. The invention presupposes an earlier experimental phase, which started with solid-wheeled carts that could only be pulled by bulls. An intermediate phase in the develop- ment is the “proto-chariot” with cross-bar wheels, attested in a BMAC-related cylinder seal from Tepe Hissar III B in northern Iran (c.2000–1900 BCE). The wooden coffins of the Sanauli royal burials provide another pointer to a possible Sintashta origin.