Bārā Culture: an Overview of Problems and Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D at a Kailash Nath Dikshit

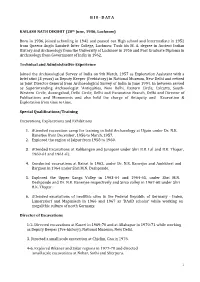

B I 0 - D AT A KAILASH NATH DIKSHIT (20th June, 1936, Lucknow) Born in 1936, joined schooling in 1942 and passed out High school and Intermediate in 1952 from Queens Anglo Sanskrit Inter College, Lucknow. Took his M. A. degree in Ancient Indian History and Archaeology from the University of Lucknow in 1956 and Post Graduate Diploma in Archaeology from Government of India in 1962. Technical and Administrative Experience Joined the Archaeological Survey of India on 9th March, 1957 as Exploration Assistant with a brief stint (3 years) as Deputy Keeper (Prehistory) in National Museum, New Delhi and retired as Joint Director General from Archaeological Survey of India in June 1994. In between served as Superintending Archaeologist 'Antiquities, New Delhi, Eastern Circle, Calcutta, South- Western Circle, Aurangabad, Delhi Circle, Delhi and Excavation Branch, Delhi and Director of Publications and Monuments and also held the charge of Antiquity and Excavation & Exploration from time to time. Special Qualifications/Training Excavations, Explorations and Exhibitions 1. Attended excavation camp for training in field Archaeology at Ujjain under Dr. N.R. Banerjee from December, 1956 to March, 1957. 2. Explored the region of Jaipur from 1958 to 1960. 3. Attended Excavations at Kalibangan and Junapani under Shri B.B. Lal and B.K. Thapar, 1960-61 and 1961-62. 4. Conducted excavations at Bairat in 1962, under Dr. N.R. Banerjee and Ambkheri and Bargaon in 1964 under Shri M.N. Deshpande. 5. Explored the Upper Ganga Valley in 1963-64 and 1964-65, under Shri M.N. Deshpande and Dr. N.R. Banerjee respectively and Sirsa valley in 1967-68 under Shri B.K. -

Sr. No District Block Name of GP Payee Co De Accounts Number

Page 1 Release of Grant Ist Installment to Gram Panchayats under the Surcharge on VAT (Normal Plan) Scheme during the Year 2017-18 Sr. District Block Name of GP Payee_co Accounts Number IFSC Name of Bank Amount in ` No de 1 Ambala AMBALA I ADHO MAJRA 8K0N5Y 163001000004021 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City 54556 2 Ambala AMBALA I AEHMA 8Q0N60 163001000004028 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City 30284 3 Ambala AMBALA I AMIPUR 8P0N61 06541450001902 HDFC0000654 HDFC, Bank Amb. City 44776 4 Ambala AMBALA I ANANDPUR JALBERA 8O0N62 163001000004012 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City136032 5 Ambala AMBALA I BABAHERI 8N0N63 163001000004037 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City 30239 6 Ambala AMBALA I BAKNOUR 8K0N66 163001000004026 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City 95025 7 Ambala AMBALA I BALAPUR 8R0N68 06541450001850 HDFC0000654 HDFC, Bank Amb. City 51775 8 Ambala AMBALA I BALLANA 8J0N67 163001000004020 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City186236 9 Ambala AMBALA I BAROULA 8P0N6A 06541450001548 HDFC0000654 HDFC, Bank Amb. City 37104 10 Ambala AMBALA I BAROULI 8O0N6B 163001000004008 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City 52403 11 Ambala AMBALA I BARRA 8Q0N69 163001000004004 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City 88474 12 Ambala AMBALA I BATROHAN 8N0N6C 06541450002021 HDFC0000654 HDFC, Bank Amb. City 65010 13 Ambala AMBALA I BEDSAN 8L0N6E 163001000004024 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City 14043 14 Ambala AMBALA I BEGO MAJRA 8M0N6D 06541450001651 HDFC0000654 HDFC, Bank Amb. City 17587 15 Ambala AMBALA I BEHBALPUR 8M0N64 06541450001452 HDFC0000654 HDFC, Bank Amb. City 32168 16 Ambala AMBALA I BHANOKHERI 8K0N6F 163001000004011 IOBA0001630 Indian Overseas Bank, Ambala City121585 17 Ambala AMBALA I BHANPUR NAKATPUR 8L0N65 06541450002014 HDFC0000654 HDFC, Bank Amb. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A&B VILLAGE, & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DIST.RICT BHIWANI Director of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana, 1995 , . '. HARYANA C.D. BLOCKS DISTRICT BHIWANI A BAWAN I KHERA R Km 5 0 5 10 15 20 Km \ 5 A hAd k--------d \1 ~~ BH IWANI t-------------d Po B ." '0 ~3 C T :3 C DADRI-I R 0 DADRI - Il \ E BADHRA ... LOHARU ('l TOSHAM H 51WANI A_ RF"~"o ''''' • .)' Igorf) •• ,. RS Western Yamuna Cana L . WY. c. ·......,··L -<I C.D. BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUtORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1 ,1. 1990 BOUNDARY , STAT E ... -,"p_-,,_.. _" Km 10 0 10 11m DI';,T RI CT .. L_..j__.J TAHSIL ... C. D . BLOCK ... .. ~ . _r" ~ V-..J" HEADQUARTERS : DISTRICT : TAHSIL: C D.BLOCK .. @:© : 0 \ t, TAH SIL ~ NHIO .Y'-"\ {~ .'?!';W A N I KHERA\ NATIONAL HIGHWAY .. (' ."C'........ 1 ...-'~ ....... SH20 STATE HIGHWAY ., t TAHSil '1 TAH SIL l ,~( l "1 S,WANI ~ T05HAM ·" TAH S~L j".... IMPORTANT METALLED ROAD .. '\ <' .i j BH IWAN I I '-. • r-...... ~ " (' .J' ( RAILWAY LINE WIT H STA110N, BROAD GAUGE . , \ (/ .-At"'..!' \.., METRE GAUGE · . · l )TAHSIL ".l.._../ ' . '1 1,,1"11,: '(LOHARU/ TAH SIL OAORI r "\;') CANAL .. · .. ....... .. '" . .. Pur '\ I...... .( VILLAGE HAVING 5000AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME ..,." y., • " '- . ~ :"''_'';.q URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE- CLASS l.ltI.IV&V ._.; ~ , POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICE ... .. .....PTO " [iii [I] DEGREE COLLE GE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION.. '" BOUNDARY . STATE REST HOuSE .TRAVELLERS BUNGALOW AND CANAL: BUNGALOW RH.TB .CB DISTRICT Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/CB elc. -

Haryana Agro Industries Corporation Limited

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) FOR SELECTION OF LOGISTICS SERVICE PROVIDER FOR SETTING UP FACILITIES IN WAREHOUSES/DELIVERY CENTRES AND PROVIDING TECH DRIVEN LOGISTICS SERVICES WITH IT IMPLEMENTATION FOR HARYANA AGRO INDUSTRIES CORPORATION LIMITED Ref No. HAICL/19-01-2021/Logistics-1 19-01-2021 E- TENDER HARYANA AGRO INDUSTRIES CORPORATION LIMITED CIN No.U51219HR1967SGC041080 Registered office EPABX: 0172-2561317, 2560920 Bays No.15-20, Sector-4 FAX: 0172-2561310, 2561313 Panchkula Website:www. haic.co.in Email: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Chapter Particulars Page No. Disclaimer 4 1 DEATIL NOTICE INVITING TENDER 5 2 KEY DATES 6 IMPORTANT NOTE 6 INSTRUCTION TO THE BIDDER IN ELECTRONIC 3 TENDERING SYSTEM 7 REGISTRATION OF THE BIDDER ON E- 3.1 PROCUREMENT PORTAL 7 3.2 OBTAINING A DISGITAL CERTIFICATE 7 3.3 PREREQUISITE FOR ONLINE BIDDING 8 ONLINE VIEWING OF DETAILED NOTICE INVITING 3.4 TENDER 8 3.5 DOWLOAD THE TNEDER DOCUMENT 8 3.6 KEY DATES 8 3.7 ONLINE PAYMENT OF TENDER FEE ETC 8 3.8 ASSISTANCE TO BIDDER 9 3.9 ONLINE PAYMENT GUIDELINES 9 4 DO AND DON’T FOR BIDDER 12 5 INTRODUCTION 14 6 TERM AND CONDITION 14 7 TERM OF REFERENCES TOR 18 7.1 PENTALY 18 7.2 VENDOR EMPLOYEE 18 7.3 IT AND IT ENABLES EQUIPMENT 18 7.4 EQUIPMENT 18 7.5 TIMELINE 18 7.6 PAYMENT SCHEDULE 18 7.7 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHT 18 7.8 FORCE MAJEURE 19 7.9 CONFIDENTIALITY 19 7.10 GOVERNING LAWS 19 7.11 INDEMNITY 19 7.12 DURATION OF CONTRACT 19 7.13 TERM AND TERMINATION 20 7.14 CONSEQUENCES OF TERMINATION 20 7.15 DISPUTE RESOLUTION 21 2 7.16 INSURANCE 21 8 OBJECTIVE -

List of QCI Certified Professionals

List of QCI Certified Professionals S.No Name Yoga Level Address Mr Ankit Tiwari Level 2 - Yoga Teacher A-21, Type-2, Police Line, Roshanabad, Haridwar, 1 Uttarakhand-249403 Mr Amit Kashyap Level 2 - Yoga Teacher 2 29/1067, Baba Kharak Singh Marg, New Delhi-110001 Ms Aashima Malhotra Level 2 - Yoga Teacher 425, Aashirwad Enclave, Plot No. 104, I.P. Extn., Delhi- 3 110092 Mr Avinash Ghasi Level 2 - Yoga Teacher Address - C-73, Aishwaryam Apartment, Plot 17, 4 Sector-4, Dwarka, New Delhi. 110078 Mr Kiran Kumar Bhukya Level 2 - Yoga Teacher H.No. 494 Chandya b Tanda Thattpalle Kuravi - 5 Warangal,-506105 6 Ms Komal Kedia Level 2 - Yoga Teacher FG-1/92B, Vikaspuri, LIG Flats, New Delhi-110018 7 Ms Neetu Level 2 - Yoga Teacher C-64-65, Kewal Park, Azadpur, Delhi-110033 Mr Pardeep Bhardwaj Level 2 - Yoga Teacher H.No. 160, Shri Shyam Baba Chowk, VPO Khera 8 Khurd, Delhi-110082 Mr Pushp Dant Level 2 - Yoga Teacher 77, Sadbhavana Apartments, Plot 13, IP Extension, 9 Delhi - 110092 Mr S.uday Kumar Level 2 - Yoga Teacher H.No. 20-134/11, Teacher's Colony, Achampet Distt., 10 Mahabubnagar, Telangana-509375 11 Mr Saurabh Grover Level 2 - Yoga Teacher C-589, Street No. 3, Ganesh Nagar-II, Delhi-110092 Ms Smita Kumari Level 2 - Yoga Teacher B-Type, Q. No. 17, Sector-3, M.O.C.P. Colony, 12 Alakdiha, P.O. Pargha Jharia, Dhanbad, Jharkhand- 82820 13 Ms Tania Level 2 - Yoga Teacher E-296, MCD Colony, Azadpur, Delhi-110033 Ms Veenu Soni Level 2 - Yoga Teacher X/3543, St. -

Unit 10 Chalcolithic and Early Iron Age-I

UNIT 10 CHALCOLITHIC AND EARLY IRON AGE-I Structure 10.0 Objectives 10.1 Introduction 10.2 Ochre Coloured Pottery Culture 10.3 The Problems of Copper Hoards 10.4 Black and Red Ware Culture 10.5 Painted Grey Ware Culture 10.6 Northern Black Polished Ware Culture 10.6.1 Structures 10.6.2 Pottery 10.6.3 Other Objects 10.6.4 Ornaments 10.6.5 Terracotta Figurines 10.6.6 Subsistence Economy and Trade 10.7 Chalcolithic Cultures of Western, Central and Eastern India 10.7.1 Pottery: Diagnostic Features 10.7.2 Economy 10.7.3 Houses and Habitations 10.7.4 Other 'characteristics 10.7.5 Religion/Belief Systems 10.7.6 Social Organization 10.8 Let Us Sum Up 10.9 Key Words 10.10 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 10.0 OBJECTIVES In Block 2, you have learnt about'the antecedent stages and various aspects of Harappan culture and society. You have also read about its geographical spread and the reasons for its decline and diffusion. In this unit we shall learn about the post-Harappan, Chalcolithic, and early Iron Age Cultures of northern, western, central and eastern India. After reading this unit you will be able to know about: a the geographical location and the adaptation of the people to local conditions, a the kind of houses they lived in, the varieties of food they grew and the kinds of tools and implements they used, a the varietie of potteries wed by them, a the kinds of religious beliefs they had, and a the change occurring during the early Iron age. -

A New Study on the Food System of Indus Valley Civilization

A new study on the food system of Indus Valley civilization December 10, 2020 In news A new study finds that Indus Valley Civilization diet had the dominance of meat Key findings of the study A new study, titled “Lipid residues in pottery from the Indus Civilisation in northwest India’’ looks at the food habit of the people of that era on the basis of lipid residue analysis found in pottery from Harappan sites in Haryana. It finds that the diet of the people of Harappan civilization had a dominance of meat, including extensive eating of beef The study also finds dominance of animal products such as meat of pigs, cattle, buffalo, sheep and goat, as well as dairy products, used in ancient ceramic vessels from rural and urban settlements of Indus Valley civilization in northwest India The study says that out of domestic animals, cattle/buffalo are the most abundant, averaging between 50% and 60% of the animal bones found, with sheep/goat accounting for 10% of animal remains. It says that the high proportions of cattle bones may suggest a cultural preference for beef consumption across Indus populations, supplemented by consumption of mutton/lamb As per the study at Harappa, 90% of the cattle were kept alive until they were three or three-and-a-half years, suggesting that females were used for dairying production, whereas male animals were used for traction. The study states that wild animal species like deer, antelope, gazelle, hares, birds, and riverine/marine resources are also found in small proportions in the faunal assemblages of both -

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT EBSTRACT As pointed out by N. G. Majumdar in 1934, a late phase of lndus civilization is illustrated by pottery discovered at the upper levels of Jhukar and Mohenjo-daro. However, it was the excavation at Rangpur which revealed in stratification a general decline in the prosperity of the Harappan culture. The cultural gamut of the nuclear region of the lndus-Sarasvati divide, when compared internally, revealed regional variations conforming to devolutionary tendencies especially in the peripheral region of north and western lndia. A large number of sites, now loosely termed as 'Late Harappan/Post-urban', have been discovered. These sites, which formed the disrupted terminal phases of the culture, lost their status as Harappan. They no doubt yielded distinctive Harappan pottery, antiquities and remnants of some architectural forms, but neither town planning nor any economic and cultural nucleus. The script also disappeared. ln this paper, an attempt is made with the survey of some of these excavated sites and other exploratory field-data noticed in the lndo-Pak subcontinent, to understand the complex issue.of Harappan decline and its legacy. CONTENTS l.INTRODUCTION 2. FIELD DATA A. Punjab i. Ropar ii. Bara iii. Dher Majra iv. Sanghol v. Katpalon vi. Nagar vii. Dadheri viii. Rohira B. Jammu and Kashmir i. Manda C. Haryana i. Mitathal ii. Daulatpur iii. Bhagwanpura iv. Mirzapur v. Karsola vi. Muhammad Nagar D. Delhi i. Bhorgarh 125 ANCiENT INDlA,NEW SERIES,NO.1 E.Western Uttar Pradesh i.Hulas il.Alamgirpur ili.Bargaon iv.Mandi v Arnbkheri v:.Bahadarabad F.Guiarat i.Rangpur †|.Desalpur ili.Dhola宙 ra iv Kanmer v.」 uni Kuran vi.Ratanpura G.Maharashtra i.Daimabad 3.EV:DENCE OF RICE 4.BURIAL PRACTiCES 5.DiSCUSS10N 6.CLASSiFiCAT10N AND CHRONOLOGY 7.DATA FROM PAKISTAN 8.BACTRIA―MARGIANAARCHAEOLOGICAL COMPLEX AND LATE HARAPPANS 9.THE LEGACY 10.CONCLUS10N ・ I. -

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia Jonathan Mark Kenoyer Felicitation Volume Edited by Dennys Frenez, Gregg M. Jamison, Randall W. Law, Massimo Vidale and Richard H. Meadow Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 917 7 ISBN 978 1 78491 918 4 (e-Pdf) © ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente, Archaeopress and the authors 2018 Front cover: SEM microphotograph of Indus unicorn seal H95-2491 from Harappa (photograph by J. Mark Kenoyer © Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Back cover, background: Pot from the Cemetery H Culture levels of Harappa with a hoard of beads and decorative objects (photograph by Toshihiko Kakima © Prof. Hideo Kondo and NHK promotions). Back cover, box: Jonathan Mark Kenoyer excavating a unicorn seal found at Harappa (© Harappa Archaeological Research Project). ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 244 Palazzo Baleani Roma, RM 00186 www.ismeo.eu Serie Orientale Roma, 15 This volume was published with the financial assistance of a grant from the Progetto MIUR 'Studi e ricerche sulle culture dell’Asia e dell’Africa: tradizione e continuità, rivitalizzazione e divulgazione' All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by The Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Jonathan Mark Kenoyer and ISMEO – Occasions in Continuum ....................................................................................v Adriano V. -

The Copper Hoards of the Indian Subcontinent: Preliminaries for an Interpretation“1

Addenda to „The Copper Hoards of the Indian Subcontinent: Preliminaries for an Interpretation“1 Paul Yule authors‘ recognition of the close relation of the Orissa Research Project 2 (DFG) hoard finds from South Haryana/North Rajasthan Chair for Asian History with the artefacts of the so-called Ganeshwar University of Kiel culture in Rajasthan (p. 83) which are related Leibnitzstr. 8 morphologically. Excavated in the early 1980s, the 24118 Kiel, Germany finds from Ganeshwar and nearby associated sites unfortunately have never been properly The above-cited study on the copper hoards and documentated and the appearance of the the archaeometallurgy of the Subcontinent went to constituent finds is still hardly known. The four press in 1987, is dated 1989, and appeared in 1992 regional/ typological groupings of hoard finds (1 abroad. It builds on my book of 1985 regarding North Rajasthan/South Haryana, 2 Doab, 3 Chota this same thematic area. Thus, I completed the Nagpur, 4 Madhya Pradesh) remain viable (M. Lal catalogue of finds and of sites (particularly those of 1983, 65-77). Worthy of discussion and research is Orissa), mapped the findspots, including those of Chakrabarti and Lahiri‘s possible connection (p. the culturally related Ochre Coloured Pottery, and 86) of the eastern hoards with the iron age Asura those of copper ore deposits, listed for the first horizon for chronological purposes. A further time the spectroscopic analyses of large numbers study attempts to integrate the eastern hoards into of hoard artefacts, and provided new interpretative a more general archaeological cultural matrix models to explain the importance and origin of the (D.K. -

Indus Valley Civilization

Indus Valley Civilization From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Extent of the Indus Valley Civilization Bronze Age This box: • view • talk • edit ↑ Chalcolithic Near East (3300-1200 BCE) Caucasus, Anatolia, Levant, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Elam, Jiroft Bronze Age collapse Europe (3200-600 BCE) Aegean (Minoan) Caucasus Basarabi culture Coț ofeni culture Pecica culture Otomani culture Wietenberg culture Catacomb culture Srubna culture Beaker culture Unetice culture Tumulus culture Urnfield culture Hallstatt culture Atlantic Bronze Age Bronze Age Britain Nordic Bronze Age Italian Bronze Age Indian Subcon tinent (3300- 1200 BCE) China (3000- 700 BCE) Korea (800- 300 BCE) arsenic al bronze writing , literatu re sword, chariot ↓ Iron Age The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) was a Bronze Age civilization (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE) that was located in the northwestern region[1] of the Indian subcontinent,[2][3] consisting of what is now mainly modern-day Pakistan and northwest India. Flourishing around the Indus River basin, the civilization[n 1] primarily centred along the Indus and the Punjab region, extending into the Ghaggar- Hakra River valley[7] and the Ganges-Yamuna Doab.[8][9] Geographically, the civilization was spread over an area of some 1,260,000 km², making it the largest ancient civilization in the world. The Indus Valley is one of the world's earliest urban civilizations, along with its contemporaries, Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. At its peak, the Indus Civilization may have had a population of well over five million. Inhabitants of the ancient Indus river valley developed new techniques in metallurgy and handicraft (carneol products, seal carving) and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin. -

Oilseeds, Spices, Fruits and Flavour in the Indus Civilisation T J

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 24 (2019) 879–887 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Oilseeds, spices, fruits and flavour in the Indus Civilisation T J. Bates Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University, United States of America ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The exploitation of plant resources was an important part of the economic and social strategies of the people of South Asia the Indus Civilisation (c. 3200–1500 BCE). Research has focused mainly on staples such as cereals and pulses, for Prehistoric agriculture understanding these strategies with regards to agricultural systems and reconstructions of diet, with some re- Archaeobotany ference to ‘weeds’ for crop processing models. Other plants that appear less frequently in the archaeobotanical Indus Civilisation record have often received variable degrees of attention and interpretation. This paper reviews the primary Cropping strategies literature and comments on the frequency with which non-staple food plants appear at Indus sites. It argues that Food this provides an avenue for Indus archaeobotany to continue its ongoing development of models that move beyond agriculture and diet to think about how people considered these plants as part of their daily life, with caveats regarding taphonomy and culturally-contextual notions of function. 1. Introduction 2. Traditions in Indus archaeobotany By 2500 BCE the largest Old World Bronze Age civilisation had There is a long tradition of Indus archaeobotany. As summarised in spread across nearly 1 million km2 in what is now Pakistan and north- Fuller (2002) it can be divided into three phases: ‘consulting palaeo- west India (Fig.