The Effects of Essential Oil Mouthrinses with Or Without Alcohol on Plaque and Gingivitis: a Randomized Controlled Clinical Study Michael C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of Chlorhexidine in Maintaining Periodontal Health

International Journal of Dentistry Research 2016; 1(1): 31-33 Review Article Importance of Chlorhexidine in Maintaining Periodontal IJDR 2016; 1(1): 31-33 December Health © 2016, All rights reserved www.dentistryscience.com Dr. Manpreet Kaur*1, Dr. Krishan Kumar1 1 Department of Periodontics, Post Graduate Institute of Dental Sciences, Rohtak-124001, Haryana, India Abstract Plaque is responsible for periodontal diseases. In order to prevent occurrence and progression of periodontal disease, removal of plaque becomes important. Mechanical tooth cleaning aids such as toothbrushes, dental floss, interdental brushes are used for removal of plaque. However, in some cases, chemical agents are used as an adjunct to mechanical methods to facilitate plaque control and prevent gingivitis. Chlorhexidine (CHX) mouthwash is the most commonly used and is considered as gold standard chemical agent. In this review, mechanism of action and other properties of CHX are discussed. Keywords: Plaque, Chemical agents, Chlorhexidine (CHX). INTRODUCTION Dental plaque is primary etiologic factor responsible for gingivitis and periodontitis [1]. Mechanical plaque control using toothbrushes, interdental brushes, dental floss prevent occurrence of gingivitis. However, in majority of population, mechanical methods of plaque control are ineffective due to less time spent[2] for plaque removal and lack of consistency. These limitations necessitate use of chemical plaque control agents as an adjunct to mechanical plaque control. Among various chemical agents, chlorhexidine (CHX) is considered to be a gold standard chemical agent for plaque control. Its structural formula consists of two symmetric 4-chlorophenyl rings and two biguanide groups connected by a central hexamethylene chain. Mechanism of action for CHX CHX is bactericidal and is effective against gram-positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria and yeast organisms. -

Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters

microorganisms Article Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters Andrea Butera , Simone Gallo * , Carolina Maiorani, Domenico Molino, Alessandro Chiesa, Camilla Preda, Francesca Esposito and Andrea Scribante * Section of Dentistry–Department of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostic and Paediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (F.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) Abstract: Periodontitis consists of a progressive destruction of tooth-supporting tissues. Considering that probiotics are being proposed as a support to the gold standard treatment Scaling-and-Root- Planing (SRP), this study aims to assess two new formulations (toothpaste and chewing-gum). 60 patients were randomly assigned to three domiciliary hygiene treatments: Group 1 (SRP + chlorhexidine-based toothpaste) (control), Group 2 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste) and Group 3 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste + probiotics-based chewing-gum). At baseline (T0) and after 3 and 6 months (T1–T2), periodontal clinical parameters were recorded, along with microbiological ones by means of a commercial kit. As to the former, no significant differences were shown at T1 or T2, neither in controls for any index, nor in the experimental -

Periodontal Practice Patterns

PERIODONTAL PRACTICE PATTERNS A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Janel Kimberlay Yu, D.D.S. Graduate Program in Dentistry The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angelo Mariotti, Advisor Dr. Jed Jacobson Dr. Eric Seiber Copyright by Janel Kimberlay Yu 2010 Abstract Background: Differences in the rates of dental services between geographic regions are important since major discrepancies in practice patterns may suggest an absence of evidence-based clinical information leading to numerous treatment plans for similar dental problems and the misallocation of limited resources. Variations in dental care to patients may result from characteristics of the periodontist. Insurance claims data in this study were compared to the characteristics of periodontal providers to determine if variations in practice patterns exist. Methods: Claims data, between 2000-2009 from Delta Dental of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, New Mexico, and Tennessee, were examined to analyze the practice patterns of 351 periodontists. For each provider, the average number of select CDT periodontal codes (4000-4999), implants (6010), and extractions (7140) were calculated over two time periods in relation to provider variable, including state, urban versus rural area, gender, experience, location of training, and membership in organized dentistry. Descriptive statistics were performed to depict the data using measures of central tendency and measures of dispersion. ii Results: Differences in periodontal procedures were present across states. Although the most common surgical procedure in the study period was osseous surgery, greater increases over time were observed in regenerative procedures (bone grafts, biologics, GTR) when compared to osseous surgery. -

View This Page

14 書香人生 B O O K S & R E V I E W S SUNDAY, APRIL 18, 2010 • TAIPEI TIMES Hardcover: US CDs Taiwan BY DAVid CHen AND Andrew C.C. HuanG Have no illusions STAFF REPORTER AND CONTRIBUTING REPORTER ‘Courtesans and Opium’ is a salacious story masquerading as a cautionary tale BY BRADLEY WINTERTON CONTRIBUTING REPORTER his classic novel’s Chinese name means “romantic illusions,” PUBLICATION NOTES Tbut the academic publishers of this new translation probably hope to catch the eye of a wider public than mere scholars with their more sensational title. It was written by someone who called himself only The Fool of Yangzhou and is dated 1848. Its first known publication was in Jane Zhang (張靚穎) The Hindsight (光景消逝) The DoLittles Fire Ex (滅火器) 1883, though for all anyone knows it Believe in Jane (我相信) From Dripping Tears, He Saw Hopes Earthquakes Standing Here (海上的人) may have been published previously in Universal Music (在眼淚中看見希望) Self-released Uloud Music another, lost edition. Uloud Music It’s about the brothels of Yangzhou, their residents and their patrons. It pre-dates two other remarkable East Asian novels on the same theme, Nagai Kafu’s Rivalry: A Geisha’s Tale [reviewed in Taipei Times March 2, 2008] and The Sing-song Girls of Shanghai by Han Banqing [reviewed in Taipei Times June 22, 2008]. COURTESANS AND OPIUM The semi-anonymous author claims in a brief preface that he’d TRANSLATED BY PATRICK HANAN spent 30 years and all his money on 328 PAGES the spurious pleasures of “false love hile China’s Super Girl of a pipa (琵琶). -

Extensions of Remarks E945 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

June 1, 2012 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E945 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS RECOGNIZING THE NORTHERN PRENATAL NONDISCRIMINATION IN RECOGNITION OF EVAN R. HIGH SCHOOL PATRIOTS ACT (PRENDA) OF 2012 CORNS UPON RECEIVING THE HERMAN ‘‘RUSTY’’ SHIPPS LEAD- ERSHIP AWARD HON. STENY H. HOYER SPEECH OF OF MARYLAND HON. BETTY McCOLLUM HON. PATRICK J. TIBERI OF OHIO IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF MINNESOTA IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, June 1, 2012 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, June 1, 2012 Mr. HOYER. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Wednesday, May 30, 2012 Mr. TIBERI. Mr. Speaker, I rise in recogni- honor and congratulate an extraordinary team tion of Evan R. Corns upon him receiving the Ms. MCCOLLUM. Mr. Speaker, I rise today of young women from Maryland’s fifth con- Herman ‘‘Rusty’’ Shipps leadership award. in opposition to the Prenatal Nondiscrimination This prestigious award is named in honor of gressional district. The Northern High School Act, PRENDA, of 2012 (H.R. 3541). Rusty Shipps, Class of 1913. The Award, be- Patriots won the 3A Maryland ‘‘state softball Every Member of the House opposes the stowed by the Ohio Wesleyan Alumni Board of finals on May 26, 2012. This is their fifth con- Directors, recognizes exemplary leadership, secutive softball state championship and ninth abhorrent practice of gender selection, includ- ing me. In Minnesota, prohibiting sex-selective stewardship, dedication, and commitment to softball championship overall. This incredible the advancement of the university. abortions has passed on a bipartisan basis in achievement was made all the more signifi- Mr. Corns’ support of his alma mater is leg- cant given the caliber of their competition. -

Classification and Diagnosis of Aggressive Periodontitis

Received: 3 November 2016 Revised: 11 October 2017 Accepted: 21 October 2017 DOI: 10.1002/JPER.16-0712 2017 WORLD WORKSHOP Classification and diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis Daniel H. Fine1 Amey G. Patil1 Bruno G. Loos2 1 Department of Oral Biology, Rutgers School Abstract of Dental Medicine, Rutgers University - Newark, NJ, USA Objective: Since the initial description of aggressive periodontitis (AgP) in the early 2Department of Periodontology, Academic 1900s, classification of this disease has been in flux. The goal of this manuscript is to Center of Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), review the existing literature and to revisit definitions and diagnostic criteria for AgP. University of Amsterdam and Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Study analysis: An extensive literature search was performed that included databases Correspondence from PubMed, Medline, Cochrane, Scopus and Web of Science. Of 4930 articles Dr. Daniel H. Fine, Department of Oral reviewed, 4737 were eliminated. Criteria for elimination included; age > 30 years old, Biology, Rutgers School of Dental Medicine, Rutgers University - Newark, NJ. abstracts, review articles, absence of controls, fewer than; a) 200 subjects for genetic Email: fi[email protected] studies, and b) 20 subjects for other studies. Studies satisfying the entrance criteria The proceedings of the workshop were were included in tables developed for AgP (localized and generalized), in areas related jointly and simultaneously published in the Journal of Periodontology and Journal of to epidemiology, microbial, host and genetic analyses. The highest rank was given to Clinical Periodontology. studies that were; a) case controlled or cohort, b) assessed at more than one time-point, c) assessed for more than one factor (microbial or host), and at multiple sites. -

Thrf-2019-1-Winners-V3.Pdf

TO ALL 21,100 Congratulations WINNERS Home Lottery #M13575 JohnDion Bilske Smith (#888888) JohnGeoff SmithDawes (#888888) You’ve(#105858) won a 2019 You’ve(#018199) won a 2019 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 KymJohn Tuck Smith (#121988) (#888888) JohnGraham Smith Harrison (#888888) JohnSheree Smith Horton (#888888) You’ve won the Grand Prize Home You’ve(#133706) won a 2019 You’ve(#044489) won a 2019 in Brighton and $1 Million Cash BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 GaryJohn PeacockSmith (#888888) (#119766) JohnBethany Smith Overall (#888888) JohnChristopher Smith (#888888)Rehn You’ve won a 2019 Porsche Cayenne, You’ve(#110522) won a 2019 You’ve(#132843) won a 2019 trip for 2 to Bora Bora and $250,000 Cash! BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 BMWYou’ve X4 won a 2019 BMW X4 Holiday for Life #M13577 Cash Calendar #M13576 Richard Newson Simon Armstrong (#391397) Win(#556520) a You’ve won $200,000 in the Cash Calendar You’ve won 25 years of TICKETS Win big TICKETS holidayHolidays or $300,000 Cash STILL in$15,000 our in the Cash Cash Calendar 453321 Annette Papadulis; Dernancourt STILL every year AVAILABLE 383643 David Allan; Woodville Park 378834 Tania Seal; Wudinna AVAILABLE Calendar!373433 Graeme Blyth; Para Hills 428470 Vipul Sharma; Mawson Lakes for 25 years! 361598 Dianne Briske; Modbury Heights 307307 Peter Siatis; North Plympton 449940 Kate Brown; Hampton 409669 Victor Sigre; Henley Beach South 371447 Darryn Burdett; Hindmarsh Valley 414915 Cooper Stewart; Woodcroft 375191 Lynette Burrows; Glenelg North 450101 Filomena Tibaldi; Marden 398275 Stuart Davis; Hallett Cove 312911 Gaynor Trezona; Hallett Cove 418836 Deidre Mason; Noarlunga South 321163 Steven Vacca; Campbelltown 25 years of Holidays or $300,000 Cash $200,000 in the Cash Calendar Winner to be announced 29th March 2019 Winners to be announced 29th March 2019 Finding cures and improving care Date of Issue Home Lottery Licence #M13575 2729 FebruaryMarch 2019 2019 Cash Calendar Licence ##M13576M13576 in South Australia’s Hospitals. -

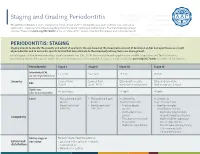

Staging and Grading Periodontitis

Staging and Grading Periodontitis The 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions resulted in a new classification of periodontitis characterized by a multidimensional staging and grading system. The charts below provide an overview. Please visit perio.org/2017wwdc for the complete suite of reviews, case definition papers, and consensus reports. PERIODONTITIS: STAGING Staging intends to classify the severity and extent of a patient’s disease based on the measurable amount of destroyed and/or damaged tissue as a result of periodontitis and to assess the specific factors that may attribute to the complexity of long-term case management. Initial stage should be determined using clinical attachment loss (CAL). If CAL is not available, radiographic bone loss (RBL) should be used. Tooth loss due to periodontitis may modify stage definition. One or more complexity factors may shift the stage to a higher level. Seeperio.org/2017wwdc for additional information. Periodontitis Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV Interdental CAL 1 – 2 mm 3 – 4 mm ≥5 mm ≥5 mm (at site of greatest loss) Severity Coronal third Coronal third Extending to middle Extending to middle RBL (<15%) (15% - 33%) third of root and beyond third of root and beyond Tooth loss No tooth loss ≤4 teeth ≥5 teeth (due to periodontitis) Local • Max. probing depth • Max. probing depth In addition to In addition to ≤4 mm ≤5 mm Stage II complexity: Stage III complexity: • Mostly horizontal • Mostly horizontal • Probing depths • Need for -

September 2013

Issue 1- September 2013 Badger Girls State Badger Boys By Rutvi Shah State By Jeremy Gartland This past summer Monika Ford Politics, leadership, sports, and I had the opportunity to represent and community. Combined, JMM at UW-Oshkosh for a program these things begin to describe the Controversal Bill... page 2 called Badger Girls State. Girls unique experience of Badger Boys The News You missed?... page 3 State is a nationwide leadership and State. A week-long government Sports... page 4 citizenship program for high school simulation sponsored by American Advice to Freshman... page 5 juniors. Delegates have the chance Legion, Badger Boys State (BBS) Entertainment... page 6 to learn about local and state govern- draws high school juniors from ments when they run for offices at across the state to participate in city, county, and state levels. The first what for many is a life-changing few days were overwhelming, but the experience was definitely worth event. it in the end! At city meetings Badger citizens decided how their cities Pulling up to Ripon College, the site of BBS since would function. Badger girls ran for various positions and they intro- its creation, I didn’t recognize duced obnoxious ordinances; for instance, the citizens of Willow Springs campaigns, law-making, and even a single face in the crowd nuclear catastrophes. After a day of made it mandatory for everyone to yell “duck and cover” when “poten- of my peers. What was also tially dangerous males” were present. getting to know my fellow citizens, clear was that no one else did I had the privilege of being elected One of the highlights of the week was attending the Badger Girls State either. -

Music-Based TV Talent Shows in China: Celebrity and Meritocracy in the Post-Reform Society

Music-Based TV Talent Shows in China: Celebrity and Meritocracy in the Post-Reform Society by Wei Huang B. A., Huaqiao University, 2013 Extended Essays Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication (Dual Degree in Global Communication) Faculty of Communication, Art & Technology © Wei Huang 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2015 Approval Name: Wei Huang Degree: Master of Arts (Communication) Title: Music-Based TV Talent Shows in China: Celebrity and Meritocracy in the Post-Reform Society Examining Committee: Program Director: Yuezhi Zhao Professor Frederik Lesage Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor School of Communication Simon Fraser University Baohua Wang Supervisor Professor School of Communication Communication University of China Date Defended/Approved: August 31, 2015 ii Abstract Meritocracy refers to the idea that whatever our social position at birth, society should offer the means for those with the right “talent” to “rise to top.” In context of celebrity culture, it could refer to the idea that society should allow all of us to have an equal chance to become celebrities. This article argues that as a result of globalization and consumerism in the post-reform market economy, the genre of music-based TV talent shows has become one of the most popular TV genres in China and has at the same time become a vehicle of a neoliberal meritocratic ideology. The rise of the ideology of meritocracy accompanied the pace of market reform in post-1980s China and is influenced by the loss of social safety nets during China’s transition from a socialist to a market economy. -

The Roots of Periodontology

THE ROOTS OF PERIODONTOLOGY NMDHA 24th Annual Scientific Session Dennis Miller DMD, MS Diplomate, American Board of Periodontology Oct 19, 2012 A word about the value of history…… Those who don’t know history are destined to repeat it. Edmond Burke (1729-1797) Those of you who don’t remember the past are condemned to repeat it. • George Santayama, 1890 The History of Dentistry • Barbers and blacksmiths were the first dentists in America • 1840 – opening of the first dental school, University of Baltimore • 1859 – ADA was founded, oldest and largest national Dental Society in the world • 1890 – Dr. John Riggs describes periodontal disease • Calls it Riggs disease or pyorrhea • Marketed Anti-Riggs mouthwash (156 proof) • 1896 – Dr. G.V. Black who is known as the father of modern dentistry, describes cavity preparations • 1906 – Dr. C. Edmund Kells exposes first dental radiograph; also the first to use female dental assistants and surgical aspirators • 1929 – Orthodontics recognized as first dental specialty History of Periodontics • 1914 – Dr. Grace Rodgers Spalding and Dr. Gillette Hayden (both physicians) formed the American Academy of Oral Prophylaxis and Periodontology • 1919 – became the American Academy of Periodontology • Circa 1941 - Periodontics recognized as a dental specialty History of Hygiene • 1867 – Lucy Hobbs Taylor graduated from Ohio College of Dental Surgery as a hygienist • 1884 – paper presented at the NY 1st District Dental Society meeting advocating teeth cleaning for prevention, done by “staff” • 1923 – formation of ADHA Historical names of periodontitis • Loculosis • Blennorrhea gingivae • Periostitis • Alveolodental periostitis • Infectious arthrodental gingivitis • Phagedenic pericementitis • Expulsive gingivitis • Symptomatic alveolar arthritis • Smutz pyorrhea • Riggs disease • Periodontoclasia • Pyorrhea alveolaris The roots of Periodontology • The roots of the dental profession including periodontics and dental hygiene were not concocted by some entrepreneur. -

Tobacco and Your Oral Health

Oral Wellness Series Tobacco and Your Oral Health We all know smoking is bad for us, but did you know that chewing tobacco is just as harmful to your oral health as cigarettes? Tobacco causes bad breath, which nobody likes, but it has far more serious risks to your oral health, including: • Mouth sores • Slow healing after oral surgery • Difficulties correcting cosmetic dental problems • Stained teeth and tongue • Dulled sense of taste and smell The Biggest Risk? Did you know tobacco Cancer. The Centers for Disease Control have linked smoking and use is a huge risk factor tobacco use to oral cancer. Oral cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the U.S., and it’s very difficult to detect. As a result, two- for gum disease? thirds of all cases are diagnosed in late stages, making treatment and survival difficult.1 Tobacco and Gum Disease Tobacco use is also a huge risk factor for gum disease, a leading cause of tooth loss. More than 41% of daily smokers over the age of 65 are toothless because of gum disease, compared to only 20% of non-smokers.2 Maintain good oral health by avoiding tobacco. It keeps your whole body healthier. The Effects of Smoking on Your Gums Smoking reduces blood flow to your gums, cutting Is Smokeless Tobacco Safer? off vital nutrients and preventing bones from healing. Smokeless tobacco—chew, dip and snuff—is not This lets bacteria from tartar infect surrounding tissue, regulated by the FDA so it’s hard to know what’s in it. 3 forming deep pockets between teeth and gums.