Volume 5 Summer 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conflict Between Liberty of Conscience and Church Authority

Reformed Theological Seminary THE CONFLICT BETWEEN LIBERTY OF CONSCIENCE AND CHURCH AUTHORITY IN TODAY’S EVANGELICAL CHURCH An Integrated Thesis Submitted to Dr. Donald Fortson In Candidacy for the Degree Of Master of Arts By Gregory W. Perry July 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………. iii 1. The Conflict between Liberty of Conscience and Church Authority Introduction…………………………………………………………………… 1 The Power Struggle…………………………………………………………… 6 2. The Bible on Liberty of Conscience and Church Authority The Liberty of the Conscience in Its Proper Place……………………………. 14 Church Authority: The Obligation to Obedience……………………………... 30 The Scope of Church Authority………………………………………………. 40 Church Discipline: The Practical Application of Church Authority………….. 54 3. The History of Liberty of Conscience and Church Authority The Reformed Conscience……………………………………………………. 69 The Puritan Conscience………………………………………………………. 81 The Evolution of the American Conscience………………………………….. 95 4. Application for Today The State of the Church Today………………………………………………. 110 The Purpose-Driven Conscience…………………………………………….. 117 Feeding the Fear of Church Authority……………………………………….. 127 Practical Implications………………………………………………………… 139 Selected Bibliography………………………………………………………………... 153 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Reverend P.G. Mathew and the elders of Grace Valley Christian Center in Davis, California for their inspiration behind this thesis topic. The first way they inspired this thesis is through their faithful preaching of God’s Word, right administration of the sacraments, and their uncompromising resolve to exercise biblical discipline. Their godly example of faithfulness in leading their flock in the manner that the Scriptures require was the best resource in formulating these ideas. The second inspiration was particularly a set of sermons that Pastor Mathew preached on Libertinism from March 28-May 2, 2004. -

ED390648.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 390 648 SE 056 959 AUTHOR Poole, Michael TITLE Beliefs and Values in Science Education. Developing Science and Technology Education. REPORT NO ISBN-0-335-15645-2 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 146p. AVAILABLE FROM Open University Press, Suite 101, 1900 Frost Road, Bristol, PA 19007 (hardcover: ISBN-0-335-15646-0; paperback: ISBN-0-335-15645-2). PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Beliefs; *Cultural Influences; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Moral Values; Science Curriculum; Science Instruction; Social Values; Student Attitudes; Technology; *Values ABSTRACT This book asserts that beliefs and values are integral to the scientific enterprise and the theory and practice of education and hence science education, and that it is desirable to explore such matters in the classroom. It aims at helping science teachers demonstrate how spiritual, moral, social, and cultural factors affect science. Chapter 1, "Everybody Needs Standards," begins by looking at ways in which beliefs and values are located within science and within education and moves on to fundamental matters about the bases of belief systems. Chapter 2, "What Science Cannot Discover, Mankind Cannot Know?" considers how beliefs about the nature of the scientific enterprise have affected popular views about the status of science, and the particular educational task this presents. The ways in which beliefs and values affect the language of science, its models, and metaphors, is the theme of chapter 3, "Every Comparison Has a Limp." Chapter 4, "Wanted! Alive or Dead," addresses issues of environmental beliefs and models. Chapcer 5, "In the Beginning," deals with teaching about the Earth in space and traces out current interest in metaphysical as well as physical questions about origin. -

Deep Carbon Science

From Crust to Core Carbon plays a fundamental role on Earth. It forms the chemical backbone for all essential organic molecules produced by living organ- isms. Carbon-based fuels supply most of society’s energy, and atmos- pheric carbon dioxide has a huge impact on Earth’s climate. This book provides a complete history of the emergence and development of the new interdisciplinary field of deep carbon science. It traces four cen- turies of history during which the inner workings of the dynamic Earth were discovered, and it documents the extraordinary scientific revolutions that changed our understanding of carbon on Earth for- ever: carbon’s origin in exploding stars; the discovery of the internal heat source driving the Earth’s carbon cycle; and the tectonic revolu- tion. Written with an engaging narrative style and covering the scien- tific endeavors of about 150 pioneers of deep geoscience, this is a fascinating book for students and researchers working in Earth system science and deep carbon research. is a life fellow at St. Edmund’s College, University of Cambridge. For more than 50 years he has passionately engaged in bringing discoveries in astronomy and cosmology to the general public. He is a fellow of the Royal Historical Society, a former vice- president of the Royal Astronomical Society and a fellow of the Geological Society. The International Astronomical Union designated asteroid 4027 as Minor Planet Mitton in recognition of his extensive outreach activity and that of Dr. Jacqueline Mitton. From Crust to Core A Chronicle of Deep Carbon Science University of Cambridge University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor, New York, NY 10006, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia 314–321, 3rd Floor, Plot 3, Splendor Forum, Jasola District Centre, New Delhi – 110025, India 79 Anson Road, #06–04/06, Singapore 079906 Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. -

The Fine-Tuning of the Universe for Intelligent Life

CSIRO PUBLISHING Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, 2012, 29, 529–564 Review http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/AS12015 The Fine-Tuning of the Universe for Intelligent Life L. A. Barnes Institute for Astronomy, ETH Zurich, Switzerland, and Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics, University of Sydney, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract: The fine-tuning of the universe for intelligent life has received a great deal of attention in recent years, both in the philosophical and scientific literature. The claim is that in the space of possible physical laws, parameters and initial conditions, the set that permits the evolution of intelligent life is very small. I present here a review of the scientific literature, outlining cases of fine-tuning in the classic works of Carter, Carr and Rees, and Barrow and Tipler, as well as more recent work. To sharpen the discussion, the role of the antagonist will be played by Victor Stenger’s recent book The Fallacy of Fine-Tuning: Why the Universe is Not Designed for Us. Stenger claims that all known fine-tuning cases can be explained without the need for a multiverse. Many of Stenger’s claims will be found to be highly problematic. We will touch on such issues as the logical necessity of the laws of nature; objectivity, invariance and symmetry; theoretical physics and possible universes; entropy in cosmology; cosmic inflation and initial conditions; galaxy formation; the cosmological constant; stars and their formation; the properties of elementary particles and their effect on chemistry and the macroscopic world; the origin of mass; grand unified theories; and the dimensionality of space and time. -

A Constructive Theology of Truth As a Divine Name with Reference to the Bible and Augustine

A Constructive Theology of Truth as a Divine Name with reference to the Bible and Augustine by Emily Sumner Kempson Murray Edwards College September 2019 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright © 2020 Emily Sumner Kempson 2 Preface This thesis is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. 3 4 A Constructive Theology of Truth as a Divine Name with Reference to the Bible and Augustine (Summary) Emily Sumner Kempson This study is a work of constructive theology that retrieves the ancient Christian understanding of God as truth for contemporary theological discourse and points to its relevance to biblical studies and philosophy of religion. The contribution is threefold: first, the thesis introduces a novel method for constructive theology, consisting of developing conceptual parameters from source material which are then combined into a theological proposal. -

Practical Objectivity: Keeping Natural Science Natural Alan G

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Faculty Publications Faculty & Staff choS larship 2012 Practical Objectivity: Keeping Natural Science Natural Alan G. Padgett Luther Seminary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/faculty_articles Part of the Christianity Commons, Philosophy of Science Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Padgett, Alan G., "Practical Objectivity: Keeping Natural Science Natural" (2012). Faculty Publications. 309. https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/faculty_articles/309 Published Citation Padgett, Alan G. “Practical Objectivity: Keeping Natural Science Natural.” In The Blackwell Companion to Science and Christianity, edited by J. B. Stump, 93–102. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty & Staff choS larship at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. st, NY: Human- 9 sily Press. Press. ress. the Science and Practical Objectivity dbnok of Religion Keeping Natural Science Natural a Feminist Cos · ckwick Publica- ALAN G. PADGETT dt!dge. A good Should natural science go natural (so to speak) or is there room in a properly natural science ieces by Code, for kinds of explanation other than natural ones? Is there room in a properly natural science for appeal to intelligent agency, for example?' This is the key question of our chapter, . Elmsford, NY: and it will take us some way into the philosophy of science and the relationship between d how biology science and Christian faith. -

When the Earth Moves Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics

This article was published in 1999 and has not been updated or revised. BEYONDBEYOND DISCOVERYDISCOVERYTM THE PATH FROM RESEARCH TO HUMAN BENEFIT WHEN THE EARTH MOVES SEAFLOOR SPREADING AND PLATE TECTONICS arly on the morning of Wednesday, April 18, the fault had moved, spanning nearly 300 miles, from 1906, people in a 700-mile stretch of the West San Juan Bautista in San Benito County to the south E Coast of the United States—from Coos Bay, of San Francisco to the Upper Mattole River in Oregon, to Los Angeles, California—were wakened by Humboldt County to the north, as well as westward the ground shaking. But in San Francisco the ground some distance out to sea. The scale of this movement did more than shake. A police officer on patrol in the was unheard of. The explanation would take some six city’s produce district heard a low rumble and saw the decades to emerge, coming only with the advent of the street undulate in front of him, “as if the waves of the theory of plate tectonics. ocean were coming toward me, billowing as they came.” One of the great achievements of modern science, Although the Richter Scale of magnitude was not plate tectonics describes the surface of Earth as being devised until 1935, scientists have since estimated that divided into huge plates whose slow movements carry the the 1906 San Francisco earthquake would have had a continents on a slow drift around the globe. Where the 7.8 Richter reading. Later that morning the disaster plates come in contact with one another, they may cause of crushed and crumbled buildings was compounded by catastrophic events, such as volcanic eruptions and earth- fires that broke out all over the shattered city. -

Download Book Reviews Section

S & CB (2009), 21, 175–192 0954–4194 Book Reviews Anna Case-Winters and allows for divine action without vio- Reconstructing a Christian Theology lation of natural laws. Other panen- of Nature: Down to Earth theisms would presumably also achieve Aldershot/Burlington VT: Ashgate, 2007. this but she sees process thought’s value 183 pp. hb. £50.00. ISBN 978-0-7546- lying within its espousal of ‘panexperi- 5476-6 mentalism’, its ‘refusal of a material-spir- itual dualism in which God and the This is an attempt, from within the human being have a monopoly of spirit Reformed tradition, to contribute and the rest of nature is simply material’ towards ‘a more viable theology of (129). It lets God off the theodical hook to nature’(1). The author considers that the some extent, and provides a non-hierar- need for such a reinterpretation of exist- chical view of reality. ing theology lies in the ‘state of the world’ (the usual ecological suspects but pre- The strength of this book is its identifi- sented within a wider canvas of econom- cation of the wider issues (not just the ics and health issues) and the ‘state of ecological crisis) facing a theology of theology’. The latter includes the obvious nature and its juxtaposition of a number accusations, from Lynn White, of dualism of different approaches to dealing with between God and World leading to the problems she identifies. If you find anthropocentrism and the desacralisa- process thought a satisfying and coher- tion of nature. However, Case-Winters ent account of the world then you may expands the challenge to include attacks find her thesis convincing. -

Plate Tectonics

Plate tectonics tive motion determines the type of boundary; convergent, divergent, or transform. Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along these plate boundaries. The lateral relative move- ment of the plates typically varies from zero to 100 mm annually.[2] Tectonic plates are composed of oceanic lithosphere and thicker continental lithosphere, each topped by its own kind of crust. Along convergent boundaries, subduction carries plates into the mantle; the material lost is roughly balanced by the formation of new (oceanic) crust along divergent margins by seafloor spreading. In this way, the total surface of the globe remains the same. This predic- The tectonic plates of the world were mapped in the second half of the 20th century. tion of plate tectonics is also referred to as the conveyor belt principle. Earlier theories (that still have some sup- porters) propose gradual shrinking (contraction) or grad- ual expansion of the globe.[3] Tectonic plates are able to move because the Earth’s lithosphere has greater strength than the underlying asthenosphere. Lateral density variations in the mantle result in convection. Plate movement is thought to be driven by a combination of the motion of the seafloor away from the spreading ridge (due to variations in topog- raphy and density of the crust, which result in differences in gravitational forces) and drag, with downward suction, at the subduction zones. Another explanation lies in the different forces generated by the rotation of the globe and the tidal forces of the Sun and Moon. The relative im- portance of each of these factors and their relationship to each other is unclear, and still the subject of much debate. -

Major Concepts That Underpin Our Current Understanding of the Earth

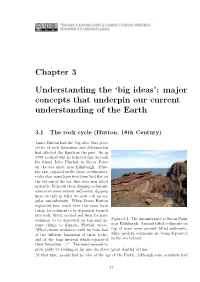

Chapter 3 Understanding the `big ideas': major concepts that underpin our current understanding of the Earth 3.1 The rock cycle (Hutton, 18th Century) James Hutton had the `big idea' that great cycles of rock formation and deformation had affected the Earth in the past. So in 1788, to show why he believed this, he took his friend John Playfair to Siccar Point on the sea shore near Edinburgh. Play- fair saw, exposed on the shore, sedimentary rocks that must have first been laid flat on the bottom of the sea, that were now tilted upwards. Beneath these dipping sediments were even more ancient sediments, dipping more steeply in what we now call an an- gular unconformity. When James Hutton explained how much time this must have taken, for sediment to be deposited, formed into rock, tilted, eroded and then for more sediment to be deposited on top and the Figure 3.1: The unconformity at Siccar Point same things to happen, Playfair wrote, near Edinburgh. Ancient tilted sediments on `What clearer evidence could we have had top of even more ancient tilted sediments, of the different formation of these rocks, while modern sediments are being deposited and of the long interval which separated in the sea behind. their formation ...?'. `The mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss [great depths] of time.' At that time, people had no idea of the age of the Earth. Although some scientists had 71 found evidence that the Earth was ancient, the general public thought that the Earth had formed only around 6000 years ago. -

Explanatory Notes for the Plate-Tectonic Map of the Circum-Pacific Region

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP SHEETS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCUM-PACIFIC PLATE-TECTONIC MAP SERIES Explanatory Notes for the Plate-Tectonic Map of the Circum-Pacific Region By GEORGE W. MOORE CIRCUM-PACIFIC COUNCIL_a t ENERGY AND MINERAL \il/ RESOURCES THE ARCTIC SHEET OF THIS SERIES IS AVAILABLE FROM U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP DISTRIBUTION BOX 25286, FEDERAL CENTER, DENVER, COLORADO 80225, USA OTHER SHEETS IN THIS SERIES AVAILABLE FROM THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF PETROLEUM GEOLOGISTS BOX 979 TULSA, OKLAHOMA 74101, USA 1992 CIRCUM-PACIFIC COUNCIL FOR ENERGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES Michel T. Halbouty, Chair CIRCUM-PACIFIC MAP PROJECT John A. Reinemund, Director George Gryc, General Chair Explanatory Notes to Supplement the PLATE-TECTONIC MAP OF THE CIRCUM-PACIFIC REGION Jose Corvalan Dv Chair, Southeast Quadrant Panel lan W.D. Dalziel, Chair, Antarctic Panel Kenneth J. Drummond, Chair, Northeast Quadrant Panel R. Wallace Johnson, Chair, Southwest Quadrant Panel George W. Moore, Chair, Arctic Panel Tomoyuki Moritani, Chair, Northwest Quadrant Panel TECTONIC ELEMENTS George W. Moore, Department of Geosciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA Nikita A. Bogdanov, Institute of the Lithosphere, Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Jose Corvalan, Servicio Nacional de Geologia y Mineria, Santiago, Chile Campbell Craddock, Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin H. Frederick Doutch, Bureau of Mineral Resources, Canberra, Australia Kenneth J. Drummond, Mobil Oil Canada, Ltd., Calgary, Alberta, Canada Chikao Nishiwaki, Institute for International Mineral Resources Development, Fujinomiya, Japan Tomotsu Nozawa, Geological Survey of Japan, Tsukuba, Japan Gordon H. Packham, Department of Geophysics, University of Sydney, Australia Solomon M. -

How Plate Tectonics Clicked

COMMENT use for understanding cells that do not NOAA communicate using electrical impulses. It is this view that has perpetuated our comparative ignorance about glia. Moreover, the exclusion of glia from the BRAIN Initiative underscores a more general problem with the project: the assumption that enough measuring of enough neurons will in itself uncover ‘emergent’ properties and, ultimately, cures for diseases1,4. Rather than simply materializing from measurements of “every spike from every neuron”1,4, better understanding and new treatments will require hypothesis-directed research. The 302 neurons and 7,000 connections that make up the nervous system of the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans were mapped in the 1970s and 80s. More than two decades later, little is understood about how the worm’s nervous system produces complex behaviours. In any major mapping expedition, the first priority should be to survey the uncharted regions. Our understanding of one half of the brain (the part comprised of astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and microglia) lags a century behind our knowledge of neurons. I believe that answers to questions about the brain and public support for a large-scale study are more likely to come from expanding the search into this unknown territory. As a first step, tools such as optogenetic meth- ods and mathematical models are needed to assess the number, distribution and properties of different kinds of glial cell The US research vessel Explorer towed a magnetometer to map fields over the sea floor in 1960. in different brain regions, and to identify how glia communicate with each other and with neurons, and what developmen- tal and physiological factors affect this.