Does Public Education Expansion Lead to Trickle-Down Growth?∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 16, No. 3 (2020) Music Performativity in the Album: Charles Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater David Landes This article analyzes a canonical jazz album through Nietzschean and perfor- mance studies concepts, illuminating the album as a case study of multiple per- formativities. I analyze Charles Mingus’ The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady as performing classical theater across the album’s images, texts, and music, and as a performance to be constructed in audiences’ minds as the sounds, texts, and visuals never simultaneously meet in the same space. Drawing upon Nie- tzschean aesthetics, I suggest how this performative space operates as “mental the- ater,” hybridizing diverse traditions and configuring distinct dynamics of aesthetic possibility. In this crossroads of jazz traditions, theater traditions, and the album format, Mingus exhibits an artistry between performing the album itself as im- agined drama stage and between crafting this space’s Apollonian/Dionysian in- terplay in a performative understanding of aesthetics, sound, and embodiment. This case study progresses several agendas in performance studies involving music performativity, the concept of performance complex, the Dionysian, and the album as a site of performative space. When Charlie Parker said “If you don't live it, it won't come out of your horn” (Reisner 27), he captured a performativity inherent to jazz music: one is lim- ited to what one has lived. To perform jazz is to make yourself per (through) form (semblance, image, likeness). Improvising jazz means more than choos- ing which notes to play. It means steering through an infinity of choices to craft a self made out of sound. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Gapitalism

Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Gapitalism Melissa W. Wright l) Routledoe | \ r"yror a rr.nciicroup N€wYql Lmdm Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Croup, an inlorma business Contents Acknowledgments xl 1 Introduction: Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Capitalism I Storylines 2 Disposable Daughters and Factory Fathers 23 3 Manufacturing Bodies 45 4 The Dialectics of Still Life: Murder,'il7omen, and Disposability 7l II Disruptions 5 Maquiladora Mestizas and a Feminist Border Politics 93 6 Crossing the FactorY Frontier 123 7 Paradoxes and Protests 151 Notes 171 Bibliography 177 Index r87 Acknowledgments I wrote this book in fits and starts over several years, during which time I benefited from the support of numerous people. I want to say from the outset that I dedicate this book to my parenrs, and I wish I had finished the manuscript in time for my father to see ir. My father introduced me to the Mexico-U.S. border at a young age when he took me on his many trips while working for rhe State of Texas. As we traveled by car and by train into Mexico and along the bor- der, he instilled in me an appreciation for the art of storytelling. My mother, who taught high school in Bastrop, Texas for some 30 years, has always been an inspiration. Her enthusiasm for reaching those students who want to learn and for not letting an underfunded edu- cational bureaucracy lessen her resolve set high standards for me. I am privileged to have her unyielding affection to this day. -

The Journal of the Duke Ellington Society Uk Volume 23 Number 3 Autumn 2016

THE JOURNAL OF THE DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 AUTUMN 2016 nil significat nisi pulsatur DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK http://dukeellington.org.uk DESUK COMMITTEE HONORARY MEMBERS OF DESUK Art Baron CHAIRMAN: Geoff Smith John Lamb Vincent Prudente VICE CHAIRMAN: Mike Coates Monsignor John Sanders SECRETARY: Quentin Bryar Tel: 0208 998 2761 Email: [email protected] HONORARY MEMBERS SADLY NO LONGER WITH US TREASURER: Grant Elliot Tel: 01284 753825 Bill Berry (13 October 2002) Email: [email protected] Harold Ashby (13 June 2003) Jimmy Woode (23 April 2005) MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY: Mike Coates Tel: 0114 234 8927 Humphrey Lyttelton (25 April 2008) Email: [email protected] Louie Bellson (14 February 2009) Joya Sherrill (28 June 2010) PUBLICITY: Chris Addison Tel:01642-274740 Alice Babs (11 February, 2014) Email: [email protected] Herb Jeffries (25 May 2014) MEETINGS: Antony Pepper Tel: 01342-314053 Derek Else (16 July 2014) Email: [email protected] Clark Terry (21 February 2015) Joe Temperley (11 May, 2016) COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Roger Boyes, Ian Buster Cooper (13 May 2016) Bradley, George Duncan, Frank Griffith, Frank Harvey Membership of Duke Ellington Society UK costs £25 SOCIETY NOTICES per year. Members receive quarterly a copy of the Society’s journal Blue Light. DESUK London Social Meetings: Civil Service Club, 13-15 Great Scotland Yard, London nd Payment may be made by: SW1A 2HJ; off Whitehall, Trafalgar Square end. 2 Saturday of the month, 2pm. Cheque, payable to DESUK drawn on a Sterling bank Antony Pepper, contact details as above. account and sent to The Treasurer, 55 Home Farm Lane, Bury St. -

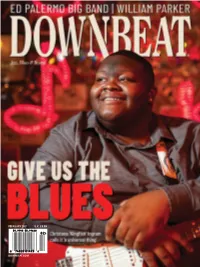

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Analysts Forum London 12 and 13 December 2007

Atos Origin Analysts Forum London 12 and 13 December 2007 Atos Origin Strategy Going Forward Phillippe Germond Chairman of the Management Board and CEO I. Welcome Good afternoon. Welcome. It is really a pleasure to have you for these two half-days. It was one of our objectives to have – for the first time as a matter of fact – this kind of meeting. Clearly it is my ambition to have this kind of meeting at least once a year so that we really have a chance to present to you what we are doing, give you some forward-looking about the company, and create – let me put it this way – some intimacy between you and the management of this company. As mentioned before, most of the management of the company is going to be with you for the two half-days. First the management board, with Wilbert Kieboom and Eric Guilhou, and probably the vast the majority of the executive committee, with the country managers and the service line managers, will be with you during these two days. So do not hesitate to listen to us answer any questions during the Q&A session later today, and really to interact with us during these two half-days. II. Two Recent Announcements Before I enter into the presentation we have been preparing for the last few weeks, I would like to make a few comments about two announcements we made yesterday night, or early this morning. I can tell you, believe it or not, it is pure coincidence that we made these two announcements. -

Primates, Monks and the Mind the Case of Empathy

Frans de Waal and Evan Thompson Interviewed by Jim Proctor Primates, Monks and the Mind The Case of Empathy Jim Proctor: It’s Monday, February 14th, Valentine’s Day, 2005. I’m pleased to welcome Evan Thompson and Frans de Waal, who have joined us as distin- guished guest scholars for a series of events in connection with a program spon- sored by UC Santa Barbara titled New Visions of Nature, Science, and Religion.1 The theme of their visit is ‘Primates, Monks, and the Mind’. What we’re going to discuss this morning — empathy — is quite appropriate to Valentine’s Day, and is one of many ways to bring primates, monks, and the mind together. I know that empathy has been important to both of you in your research. So we will explore possible overlap in the ways that someone inter- ested in the relationship between phenomenology and neuroscience — or ‘neurophenomenology’ — and someone with a background in cognitive ethol- ogy come at the question of empathy. I’d like to start by making sure we frame empathy in a common way. What would you say are the defining features of this capacity we’re calling empathy? Frans De Waal: At a very basic level, it is connecting with others, both emo- tionally and behaviourally. So, if you show a gesture or a facial expression, I may actually mimic it. There’s evidence that people unconsciously mimic the facial expression of others, so that when you smile, I smile (Dimberg et al., 2000). At the higher levels, of course, it is more of an emotional connection — I am affected by your emotions; if you’re sad, that gives me some sadness. -

Family Album

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Family Album Mary Elizabeth Bowen University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Bowen, Mary Elizabeth, "Family Album" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 909. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/909 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Album A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Mary Elizabeth (Missy) Bowen B.A., Grinnell College, 1981 May, 2009 © 2009, Mary Elizabeth (Missy) Bowen ii Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... -

Music Genre Classification Revisited: an In-Depth Examination Guided By

Music Genre Classification Revisited: An In-Depth Examination Guided by Music Experts Haukur Pálmason1, Björn Þór Jónsson1;2, Markus Schedl3, and Peter Knees4 1 Reykjavík University, Iceland 2 IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark 3 Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria 4 TU Wien, Austria [email protected] Abstract. Despite their many identified shortcomings, music genres are still often used as ground truth and as a proxy for music similarity. In this work we therefore take another in-depth look at genre classification, this time with the help of music experts. In comparison to existing work, we aim at including the viewpoint of different stakeholders to investigate whether musicians and end-user music taxonomies agree on genre ground truth, through a user study among 20 professional and semi-professional music protagonists. We then compare the results of their genre judgments with different commercial taxonomies and with that of computational genre classification experiments, and discuss individual cases in detail. Our findings coincide with existing work and provide further evidence that a simple classification taxonomy is insufficient. Keywords: music genre classification, expert study, ground truth 1 Introduction In the last 20 years, almost 500 publications have dealt with the automatic recog- nition of musical genre [21]. However, genre is a multifaceted concept, which has caused much disagreement among musicologists, music distributors, and, not least, music information retrieval (MIR) researchers [18]. Hence, MIR research has often tried to overcome the “ill-defined” concept of genre [16, 1]. Despite all the disagreement, genres are still often used as ground truth and as a proxy for music similarity and have remained important concepts in production, circula- tion, and reception of music in the last decades [4]. -

130 Charles Mingus and the Paradoxical Aspects of Race As Reflected in His Life and Music by Ernest Aaron Horton Bachelor Of

Charles Mingus and the Paradoxical Aspects of Race as Reflected in His Life and Music by Ernest Aaron Horton Bachelor of Music, University of North Texas, 1998 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 130 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Ernest Aaron Horton It was defended on March 19, 2007 and approved by Akin Euba, PhD, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Music Laurence Glasco, PhD, Associate Professor of History Mathew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor of Music Dissertation Advisor: Nathan Davis, PhD, Professor of Music ii Copyright © by Ernest Aaron Horton 2007 iii Charles Mingus and the Paradoxical Aspects of Race as Reflected in His Life and Music Ernest Aaron Horton, MA University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Charles Mingus was a jazz icon who helped to redefine the barriers that were inherent for those whose artistic expression was labeled jazz. He was a master bassist in an expressive style that was forced to fight and claw its way to respectability; he crafted challenging and emotional performances in venues where the ring of the cash register competed with his music during performances; and he developed musical techniques that had an immediate impact on American music, though he was never invited to fill any academic post. These contradictions are all brought together in light of his status as a jazz icon. The term “jazz” represents a paradox because it is the word used to represent a musical style developed in the United States and closely, but not exclusively, tied to the African-American experience. -

How Did Jazz Become a ‘High’ Art?

How did Jazz become a ‘high’ art? Adrianna Christmas-Rutledge Arts Management Senior Submitted for SPEA Undergraduate Honors Thesis Presentations Dr. Michael Rushton Director Arts Administration Program Faculty Mentor Christmas-Rutledge 2 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………3 Early Jazz: Popularity and Criticisms……………………………………………..4 The Swing Era……………………………………………………………………..8 Bebop: The Turning Point………………………………………………………...11 Jazz and Politics…………………………………………………………………..13 Jazz in Academia………………………………………………………………….16 Jazz and Governmental Funding………………………………………………….19 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………...22 Current Trends…………………………………………………………………….23 References………………………………………………………………………...25 Christmas-Rutledge 3 Abstract In American society, jazz is held in high regard as an authentic American art form. Currently, jazz programs receive a significant amount of government and private support. However in 1965, when the National Endowment for the Arts was formed, jazz was not funded. How did this popular dance music become viewed as a sophisticated, elite music? This study traces the evolution of jazz into a high art form. The study will examine three factors of this evolution: 1) societal values historically placed on jazz over the years 2) governmental funding of jazz programs and education, and 3) the reasoning behind policy decisions to fund jazz programs. The study will first examine the evolution of jazz as a popular dance medium into a recorded medium. It will also explore the value society has placed on jazz from its peak in the 1930’s, its decline in the 1950’s and 1960’s, and finally its reemergence as a high art form. Secondly, the study will examine the National Endowment for the Arts’ gradual inclusion of jazz education and performance projects. Lastly, the study will analyze data National Endowment for the Arts officials use to justify funding jazz.