Maintenance of State Prisons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Directory

2019 Directory Page 1 Page 2 Georgia Sheriffs’ Association Annual Directory Table of Contents Georgia Sheriffs’ Association Ads - alphabetically listed Welcome .................................................................................................. 4 Brannen Motor Company .......................................outside back cover Officers ..................................................................................................... 5 Combined Public Communications .................................................. 42 Active Past Presidents ............................................................................ 6 Concerns of Police Survivors, Georgia Chapter ............................... 93 Regional Vice Presidents ....................................................................... 7 CorrectHealth ......................................................................................... 1 Regional Map .......................................................................................... 8 Correctional Resource Group ............................................................... 2 Board of Directors .................................................................................. 9 Eagle Advantage Solutions ........................................ inside back cover Ed’s Public Safety .................................................................................. 58 Georgia Sheriffs’ Youth Homes Georgia Sheriffs’ Association Chaplains Division .............................. 2 Mission .................................................................................................. -

History Today Stations

GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS |FIRE SERVICES DEPARTMENT History • Certifications: Firefighter 1 and First Aid • Serves Butts, Monroe, Lamar, Spalding and Henry The program was established by Chief Buddy Brooks in 1963 counties at the Georgia Industrial Institute, which is now Lee Arrendale State Prison. The program consisted of one fire station, eight in- DODGE STATE PRISON, Station No. 3 mate firefighters and one part-time staff person assigned to the • Established in 1985 and renamed Melvin Alfonso Stephens station. Memorial Fire Station in 2004 • Responds to an average of 125 calls per year Today • Certifications: Firefighter 1, First Aid, Hazardous Materi- als, Crash Victim Extrication, and Emergency Medical The Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) operates: Responder • 19 Fire Stations in State facilities, six in county facilities • Serves Bleckley, Dodge and Laurens counties • Seven boot camps and probation detention centers have trained wildfire teams who assist the Georgia Forestry GEORGIA STATE PRISON, Station No. 4 Commission on wildfires in the North Georgia Mountains. • Established in 1965 • Responds to an average of 115 calls per year More than 220 offenders participate in the offender firefighter • Certifications: Firefighter 1 and First Aid program. GDC fire stations respond to more than 3,000 calls • Serves Tattnall, Toombs, Long and Candler counties annually. Responses have increased over 600% since 1993. LEE STATE PRISON, Station No. 5 • Established in 1986 MISSION • Responds to an average of 230 calls per year The fire services program provides fire protection to state • Certifications: Firefighter 1, First Aid and Hazardous property and the community surrounding the prisons. Materials Awareness and Operations CAREER OPPORTUNITIES • Serves Lee county Georgia legislature amended the firefighter certification require- MONTGOMERY STATE PRISON, Station No. -

Inmate Statistical Profile

Inmate Statistical Profile Inmates Admitted During CY 2007 for Any Drug Crime Produced for General Distribution Georgia Department of Corrections Operations, Planning, and Training Division Planning and Analysis Section 01-DEC-10 Georgia Dept of Corrections Inmate Statistical Profile 01-DEC-10 Contents Inmates Admitted During Cy 2007 For Any Drug Crime Produced for General Distribution Table of Contents Demographic information 5 Race group 6 Hispanic Origin 7 Marital status, self-reported at entry to prison 8 Number of children, self-reported at entry to prison 9 Religious affiliation, self-reported at entry to prison 10 Home county - self-reported at entry to prison 15 Socioeconomic class, self-reported at entry to prison 16 Environment to age 16, self-reported at entry to prison 17 Guardian status to age 16, self-reported at entry to prison 18 Employment status before prison, self-reported at entry to prison 19 Age at admission 21 Height, measured at entry to prison 22 Weight, measured at entry to prison 24 Military service Correctional information 25 Type of admission to prison 26 Current / last security status 27 Current / last institution type 28 Institution type - transitional centers 29 Institution type - county prisons 30 Institution type - state prisons 32 Institution type - private prisons 33 Institution type - prison annexes 34 Institution type - pre-release centers 35 Institution type - inmate boot camp 36 Number of disciplinary reports 37 Number of transfers 38 Number of escapes 39 Probable future release type of still active -

Georgia Department of Corrections 2014 Annual PREA Report

Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) 2014 Annual Report Georgia Department of Corrections 2014 Annual PREA Report Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) Annual Report - 2014 Georgia Department of Corrections Introduction The Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003 (PREA) was signed into federal law with the purpose to provide for the analysis of incidence and effects of prison rape in Federal, State and local institutions and to provide information, resources, recommendations and funding to protect individuals from prison rape. In 2012, the Bureau of Prisons published standardized guidelines promulgated by the Attorney General of the United States. PREA applies to all public and private institutions that house adult or juvenile offenders. The Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) maintains a zero-tolerance policy regarding sexual abuse and harassment of offenders within the agency’s 33 state prison facilities, 13 transitional centers, 8 probation detention centers, 6 substance abuse and integrated treatment facilities, 23 county correctional institutions and 4 private prisons. All potential PREA cases are reported through notifications to the Special Agents in Charge of the Office of Professional Standards and to the Statewide PREA Coordinator. The cases are documented in the form of incident reports and are entered into an internal offender management program (SCRIBE) as well as maintained at the originating facility in which the allegation was made. Allegations can be administratively or criminally investigated depending on the nature of the alleged incident. The Statewide PREA Coordinator tracks the progress of the investigations with constant contact with the facility in which the allegation was made and with the investigator that is assigned to the case, if applicable. -

Phone Street City State Zip+4

Institution Phone Street City State Zip+4 Anchorage Correctional Complex 907-334-2381 1400 East Fourth Ave Anchorage AK 99501 Anvil Mountain Correctional Center 907-443-2241 1810 Center Creek Rd. P.O. Box 730 Nome AK 99762 Fairbanks Correctional Center 907-458-6700 1931 Eagan Avenue Fairbanks AK 99701 Goose Creek Correctional Center 907-864-8100 22301 West Alsop Road Wasilla AK 99687 Highland Mountain Correctional Center 907-694-9511 9101 Hesterberg Road Eagle River AK 99577 Ketchiken Correctional Center 907-228-7350 1201 Schoenbar Road Ketchiken AK 99901-6270 Lemon Creek Correctional Center 907-465-6200 2000 Lemon Creek Rd Jueanu AK 99801 Mat-Su Pretrial 907-745-0943 339 East Dogwood Ave Palmer AK 99645 Palmer Correctional Center 907-745-5054 P.O. Box 919 Palmer AK 99645 Pt. McKenzie Correctional Farm 907-376-2976 P.O. Box 877730 Wasilla AK 99687 Spring Creek Correctional Center 907-224-8200 3600 Bette Cato Seward AK 99664 Wildwood Correctional Complex 907-260-7200 10 Chugach Avenue Kenai AK 99611 1000 Chief Eddie Hoffman Highway, PO Yukon Kushkokwim Correctional Center 907-543-5245 Bethel AK 99559 Box 400 Bibb Correctional Facility (205) 926-5252 565 Bibb Lane Brent AL 35034 Bullock Correctional Facility (334) 738-5625 P.O. Box 5107 Union Springs AL 36089 Donaldson Correctional Facility (205) 436-3681 100 Warrior Lane Bessemer AL 34023 Draper Correctional Facility (334) 567-2221 P.O. Box 1107 Elmore AL 36025 Esterling Correctional Facility (334) 397-4471 200 Wallace Drive Clio AL 36017 Elmore Correctional Facility (334) 567-1460 3520 Marion Spillway Rd. -

Georgia DOC Food Q2 2016

Georgia DOC Food Q2 2016 QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION WEIGHT TOTAL PRICE TOTAL QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION WEIGHT TOTAL PRICE TOTAL WEIGHT PRICE WEIGHT PRICE BEANS DRINK MIXES (cont.) 5940 Sevilla 4.4 oz. HOT Chili Flavor Refried... [K C H] 4.8 oz. $1.30 80001733 Wyler's Light .63 oz. Raspberry Lemonade Singles to... 1.2 oz. $4.30 4940 Velveeta 4 oz. Spicy, Cheesy Refried Beans [K C H] 4.5 oz. $1.45 MEAT SNACKS 4941 Velveeta 4 oz. Spicy, Cheesy Refried Beans &... [K C H] 4.5 oz. $1.50 5885 Brookfield Farms 2.1 oz. Fully Cooked Hickory... 3.6 oz. $6.25 CANDY 6354 Jack Link's 4 oz. Deli Cuts Sausage Bites 4.3 oz. $5.65 6330 GoLightly 2.75 oz. Sugar Free Starlight... [K C G] 3.2 oz. $2.50 80001739 Brushy Creek 5 oz. Beef Salami Summer Sausage 5.1 oz. $3.50 6331 GoLightly 2.75 oz. Sugar Free Vanilla Caramels [K C] 3.9 oz. $2.65 80001715 Brushy Creek 1.625 oz. Regular Summer Sausage 1.6 oz. $1.65 603 Werther's 5.5 oz Candy 8.0 oz. $5.00 10721 Jack Link's 1 oz. Teriyaki Beef Steak 1.6 oz. $2.80 80002888 Cinamo Candy Stick .7 oz (10 pk.) 7.2 oz. $3.00 3257 Jack Link's 2.4 oz. Screamin' Demon HOT!... [C] 2.6 oz. $2.40 CEREAL/GRANOLA/CEREAL BARS 2781 Jack Link's 1.2 oz. Sizzled Beef & Jalapeno Cheese... 1.6 oz. $2.45 PASTRIES & SNACK CAKES 10807 Kellogg's 12.2 oz. -

Inmate Statistical Profile

Inmate Statistical Profile Active Lifers Produced for General Distribution Georgia Department of Corrections Operations, Planning, and Training Division Planning and Analysis Section 07-MAR-09 Georgia Dept of Corrections Inmate Statistical Profile 07-MAR-09 Contents Active Lifers Produced for General Distribution Table of Contents Demographic information 5 Current age, broken out in ten year age groups 6 Race group 7 Hispanic Origin 8 Marital status, self-reported at entry to prison 9 Number of children, self-reported at entry to prison 10 Religious affiliation, self-reported at entry to prison 11 Home county - self-reported at entry to prison 16 Socioeconomic class, self-reported at entry to prison 17 Environment to age 16, self-reported at entry to prison 18 Guardian status to age 16, self-reported at entry to prison 19 Employment status before prison, self-reported at entry to prison 20 Age at admission 22 Age at release 23 Height, measured at entry to prison 24 Weight, measured at entry to prison 26 Military service Correctional information 27 Type of admission to prison 28 Current / last security status 29 Current / last institution type 30 Institution type - transitional centers 31 Institution type - mental hospitals 32 Institution type - county prisons 33 Institution type - state prisons 35 Institution type - private prisons 36 Institution type - prison annexes 37 Institution type - pre-release centers 38 Institution type - inmate boot camp 39 Number of disciplinary reports 40 Number of transfers Georgia Dept of Corrections Inmate -

The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation

The Correctional Peace Offi cers Foundation Taking Care of Our Own... My name is Charleene (title) and place of employment within the Georgia Corby and I am with the Correc- DOC. This includes Central Offi ce and Paroles. We tional Peace Offi cers (CPO) Foundation. If this is will request a brief description of the catastrophic the fi rst time that you are reading and learning event that is taking place in the family. about the only national charity for those that work in the Corrections Profession – WELCOME . To become a Supporting Member of the CPO Foundation simply fi ll out the application in this The CPO Foundation was created in the early 1980s newsle er or go on line at cpof.org to download by fi ve Correctional Offi cers, four of whom worked an application. Fill it out completely and mail it at Folsom State Prison in California at that time, in. The minimum contribution to become a Sup- while the fi V h was in the California Youth Author- porting Member is only $5.00 a month. It will be ity. These fi ve Correctional Offi cers had a vision. the best $5.00 you will ever donate, ensuring that when one of your fellow Offi cers – or perhaps you In the late 70s and early 80s, 20 Correctional Offi - yourself or an immediate family member -- experi- cers and Staff were killed in the line of duty in Cali- ences an emergency or catastrophic situation, help fornia. There was NO ONE and NO ORGANIZA- is there from the CPOF Catastrophic Assistance TION to help these Offi cers’ families. -

2018 Directory

2018 Directory PLATINUMPLATINUM MEMBERMEMBER GeorgiaGeorgia Sheriffs’Sheriffs’ AssociationAssociation GeorgiaGeorgia Sheriffs’Sheriffs’ YouthYouth HomeHomes PLATINUMPLATINUM MEMBERMEMBER GeorgiaGeorgia Sheriffs’Sheriffs’ AssociationAssociation GeorgiaGeorgia Sheriffs’Sheriffs’ YouthYouth HHomeomes PAGE 1 PAGE 2 GEORGIA SHERIFFS’ ASSOCIATION ANNUAL DIRECTORY Georgia Sheriffs’ Association Officers . .5 Georgia Sheriffs’ Association Past Presidents . .6 Georgia Sheriffs’ Youth Homes Officers and Past Presidents . .7 Regional Vice Presidents . .8 Regional Map . .9 Georgia Sheriffs’ Association Board of Directors . .13 Sheriffs of Georgia . .14 Sheriffs Serving on State Boards . .40 Georgia Sheriffs’ Association and Youth Homes Staff . .49 Georgia Sheriffs’ Youth Homes Campus Information . .53 Law Enforcement Training Academies . .57 State Prisons, County Prisons and Detention Centers . .58 Georgia Police Departments . .60 Members of the General Assembly . .67 Frequently Used Addresses and Phone Numbers . .72 Georgia State Patrol and GBI Phone Numbers . .75 Sheriffs’ Offices Websites . .78 Sheriffs’ Resources and Services . .80 Sheriffs’ Offices 24/7 Phone Numbers . .82 Sheriffs’ Offices Fax Numbers . .83 Sheriffs’ Addresses and Phone Numbers . .85 Cities in Georgia by County . .88 Alphabetical Listing of Sheriffs . .90 Advertiser Listing . .92 Platinum and Corporate Members . .96 Volume 37 • 2018 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR J. Terry Norris EDITOR Kim Slack CO-EDITOR Christie Luman THE GEORGIA SHERIFFS’ ANNUAL DIRECTORY is published by the Georgia -

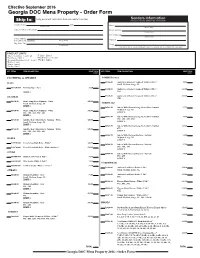

Georgia DOC Mens Property 2016 - Order Form QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE TOTAL QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE TOTAL PRICE PRICE

Effective September 2016 Georgia DOC Mens Property - Order Form PRODUCT LIMITS 1 Men's Underwear - Limit 1 pk 7 T-Shirts - Limit 4 2 Necklaces - Limit 1 8 Watch Batteries - Limit 1 3 Religious Medallions Only - Limit 1 9 Watches - Limit 1 4 Robes - Limit 1 5 Shoes - Limit 1 6 Socks - Limit 3 QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE TOTAL QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE TOTAL PRICE PRICE CLOTHING & APPAREL T-SHIRTS (cont.) 7 HATS 53185-01 Andrew Scott Select Crewneck T-Shirt (3 Pk.) $9.95 Small, Medium, Large, XL 5017201009 Stocking Cap - Navy $2.20 53185-01 Andrew Scott Select Crewneck T-Shirt (3 Pk.) 7 $13.25 LIMIT 1 2XL 7 PAJAMAS 53185-01 Andrew Scott Select Crewneck T-Shirt (3 Pk.) $13.95 3XL 50610-01 Men's Long Sleeve Pajamas - White $25.95 Small, Medium, Large, XL THERMALS LIMIT 1 50543-99 Indera Mills Thermal Long Sleeve Shirt - Natural $7.75 50610-01 Men's Long Sleeve Pajamas - White $29.95 Medium, Large, XL 2XL, 3XL, 4XL, 5XL, 6XL LIMIT 1 LIMIT 1 50543-99 Indera Mills Thermal Long Sleeve Shirt - Natural $8.95 50765-01 Innstyle Men's Short Sleeve Pajamas - White $25.95 2XL, 3XL, 4XL, 5XL Small, Medium, Large, XL LIMIT 1 LIMIT 1 50543-99 Indera Mills Thermal Long Sleeve Shirt - Natural $13.25 50765-01 Innstyle Men's Short Sleeve Pajamas - White $29.95 6XL 2XL, 3XL, 4XL, 5XL, 6XL LIMIT 1 LIMIT 1 50544-99 Indera Mills Thermal Drawers - Natural $5.50 ROBES Medium, Large, XL LIMIT 1 5199701001 Terry Velour Bath Robe - White 4 $49.95 50544-99 Indera Mills Thermal Drawers - Natural $7.95 5199702001 Terry Velour Bath Robe - White (Jumbo) 4 $52.95 -

Georgia Department of Corrections

Georgia Department of Corrections eRFP (Event) Number 46700‐GDC0000669 Additional Scored Response Document Attachment K June 9, 2015 Submitted By: Global Tel*Link Corporation 12021 Sunset Hills Road, Suite 100 Reston, VA 20190 Primary Contact: Alternate Contact: Don Eades, Account Executive Larry Eveslage , RFP Director Telephone: 770‐329‐2113 Telephone: 972‐215‐0133 Email: [email protected] Fax: 972‐506‐8783 Email: [email protected] Georgia Department of Corrections eRFP Number 46700‐GDC0000669 Inmate Telephone Service STATE OF GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS ADDITIONAL SCORED RESPONSE DOCUMENT Attachment K GDC is requesting additional information regarding potential value‐added technologies, solutions and support. Contractors are encouraged (but not required) to provide a complete written response to each of the additional scored items listed in Attachment K of the eRFP. Several of the additional scored items may require Contractor to provide exhibits and/or visual aids which clearly reference the specific eRFP section. All information contained in Contractor’s response shall be relevant to the section or specified item of the eRFP. Please note, GDC will not be a “beta test site” for any unproven technology. DO NOT INCLUDE ANY COST/PRICING/REVENUE SHARE INFORMATION IN YOUR RESPONSE TO THIS ATTACHMENT K – ADDITIONAL SCORED RESPONSE DOCUMENT. AS1: Continuous Voice Biometric Technology: Contractor shall provide an overview of its continuous voice biometric technology, detail the enrollment process and the continuous verification of the inmate’s voice. This feature must be an integrated part of the ITS and shall include analytical tools and reporting. Response: GTL understands and complies. Voice Biometric Verification GTL’s ITS includes integrated voice biometric identification. -

BOARD of CORRECTIONS April 13, 2017 Glennville, Georgia

BOARD OF CORRECTIONS April 13, 2017 Glennville, Georgia MEMBERS PRESENT: Mr. Jerry Willis, Chairman Mr. Mr. Duke Blackburn Mr. Mike Coggins Mr. Mac Collins Mr. Wayne Dasher Mr. Carl Franklin Sheriff Roger Garrison Mr. Larry Haynie Mr. Tommy M. Rouse Mr. Alton Russell Ms. Andrea Shelton Mr. W. D. Strickland Ms. Rocio D. Woody MEMBERS ABSENT: Mr. Christopher Clark Mr. Bruce Hudson Sheriff Stacy Jarrard Mr. John Mayes Ms. Rose Williams DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS: Mr. Gregory C. Dozier, Commissioner Mr. Ricky Myrick, Assistant Commissioner Mr. Scott Poitevint, Assistant Commissioner Mr. Jay Sanders, Assistant Commissioner Mr. Randy Sauls, Assistant Commissioner Mr. Timothy C. Ward, Chief of Staff Ms. Tanya Averett, LPN, Rutledge State Prison Mr. Hal Gibson, Director of Engineering & Construction Services Ms. Cassie Hargrove, Central Region Ms. Joan Heath, Director of Public Affairs Ms. Tracy Jackson, RN, Coastal State Prison Ms. Simone Juhmi, Board Liaison Mr. Keith Lank, Fugitive Unit Mr. Gary Lister, Vocational Director, Inmate Services Division Mr. Clay Nix, Assistant Director of Office of Professional Standards Ms. Amalia Nunes, LPN, Central State Prison Ms. Amy Pataluna, Interim Director, Georgia Correctional Industries Ms. Anne Pye, RN, Burruss Correctional Training Center Mr. Bryan Redfern, Correctional Officer, Montgomery State Prison Mr. Anthony Russell, Correctional Officer, Rutledge State Prison Mr. Brian White, Correctional Officer, Rogers State Prison Mr. Douglas Williams, Warden of Smith State Prison Ms. Linda Young, Correctional Officer, Emanuel Women’s Facility ATTORNEY GENERAL’S OFFICE: Mr. Rebecca Dobas, Assistant Attorney General Mr. Joseph Drolet, Senior Assistant Attorney General VISITORS: Ms. Martha Ansley, Georgia Correctional Healthcare Ms. Lynn Bill, Georgia Correctional Healthcare Mr.