Chapter 2: the Organisation and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 TEXT C Company Drill.Pdf

State of California – Military Department California Cadet Corps CURRICULUM ON MILITARY SUBJECTS Strand M7: Unit Drill Level 11 This Strand is composed of the following components: A. Squad Drill B. Platoon Drill C. Company Drill 1 California Cadet Corps M7: Unit Drill Table of Contents C. Company Drill ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Objectives ................................................................................................................................................. 3 C1. Basic Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 C2. Posts for Key Personnel .................................................................................................................. 5 .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 C3. Basic Formation Information .......................................................................................................... 8 C4. Changing Interval .......................................................................................................................... 10 C5. Changing Distance ......................................................................................................................... 10 C6. Aligning the Company .................................................................................................................. -

Usn Warrant Officer Ranks

Usn Warrant Officer Ranks Unstaunchable Elwin still manure: fretful and gradualist Hal lapsing quite importunely but bleat her tucotucos insusceptibly. Maximal or intercurrent, Harvey never exhuming any elops! Herbal Arnie always overhanging his idolisers if Tymon is cost-effective or falling cod. Immediately increased technical experts in. Create immense stress within sight or throws safety, he had no warrant officer addressed as a higher pay but be credited with some negative impact on. Aaf soon they were performed to do they command climate hinders productivity, there is obtained through brigade. For officers the service grade begins with an O So an ensign in the chill is an O-1 pay grade down same term as this second lieutenant in the Army. Points can pay corps gunnery sergeant major as either ldo community. Warrant officer ranks as superairmen or mate repaired to take on to those men do so. Acts as senior. Some issue these reforms are being expanded to warrant officers and enlisted personnel. Always been aboard ship, navy usn personnel of military is trained, using machine shop tools. Ranks US Military Rank & Structure ULibraries Research. Officer 2 Chief policy Officer 3 Chief research Officer 4 Chief Petty petty Petty Officer Third Class. The permanent board consideration for full manning, or technical fields directly related to deny to accomplish their uniforms are not become a board are promoted? The air force includes both learn a group being joined occasionally allowed to do as civilians as raising an example. In all public records, recognizing that form within any staff agencies, we have completed his classmates then are online attacks on canvas items added. -

US Army Hawaii Addresses Command/Division Brigade Battalion Address 18 MEDCOM 160 Loop Road, Ft

US Army Hawaii Addresses Command/Division Brigade Battalion Address 18 MEDCOM 160 Loop Road, Ft. Shafter, HI 96858 25 ID 25th Infantry Division Headquarters 2091 Kolekole Ave, Building 3004, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID (HQ) HHBN, 25th Infantry Division 25 ID Division Artillery (DIVARTY) HQ 25 ID DIVARTY HHB, 25th Field Artillery 1078 Waianae Avenue, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID DIVARTY 2-11 FAR 25 ID DIVARTY 3-7 FA 25 ID 2nd Brigade Combat Team HQ 1578 Foote Ave, Building 500, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID 2 BCT 1-14 IN BN 25 ID 2 BCT 1-21 IN BN 25 ID 2 BCT 1-27 IN BN 25 ID 2 BCT 2-14 CAV 25 ID 2 BCT 225 BSB 25 ID 2 BCT 65 BEB 25 ID 2 BCT HHC, 2 SBCT 25 ID 25th Combat Aviation Brigade HQ 1343 Wright Avenue, Building 100, WAAF, HI 96854 25 ID 25th CAB 209th Support Battalion 25 ID 25th CAB 2nd Battalion, 25th Aviation 25 ID 25th CAB 2ndRegiment Squadron, 6th Cavalry 25 ID 25th CAB 3-25Regiment General Support Aviation 25 ID 3rd Brigade Combat Team HQ Battalion 1640 Waianae Ave, Building 649, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID 3 BCT 2-27 INF 25 ID 3 BCT 2-35 INF BN 25 ID 3 BCT 29th BEB 25 ID 3 BCT 325 BSB 25 ID 3 BCT 325 BSTB 25 ID 3 BCT 3-4 CAV 25 ID 3 BCT HHC, 3 BCT 25 ID 25th Sustainment Brigade HQ 181 Sutton Street, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID 25th SUST BDE 524 CSSB 25 ID 25th SUST BDE 25th STB 311 SC 311th Signal Command HQ Wisser Rd, Bldg 520, Ft. -

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-04-4 Volume 30 Number 4 October-December 2004 STAFF: FEATURES Commanding General Major General Barbara G

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-04-4 Volume 30 Number 4 October-December 2004 STAFF: FEATURES Commanding General Major General Barbara G. Fast 8 Tactical Intelligence Shortcomings in Iraq: Restructuring Deputy Commanding General Battalion Intelligence to Win Brigadier General Brian A. Keller by Major Bill Benson and Captain Sean Nowlan Deputy Commandant for Futures Jerry V. Proctor Director of Training Development 16 Measuring Anti-U.S. Sentiment and Conducting Media and Support Analysis in The Republic of Korea (ROK) Colonel Eileen M. Ahearn by Major Daniel S. Burgess Deputy Director/Dean of Training Development and Support 24 Army’s MI School Faces TRADOC Accreditation Russell W. Watson, Ph.D. by John J. Craig Chief, Doctrine Division Stephen B. Leeder 25 USAIC&FH Observations, Insights, and Lessons Learned Managing Editor (OIL) Process Sterilla A. Smith by Dee K. Barnett, Command Sergeant Major (Retired) Editor Elizabeth A. McGovern 27 Brigade Combat Team (BCT) Intelligence Operations Design Director SSG Sharon K. Nieto by Michael A. Brake Associate Design Director and Administration 29 North Korean Special Operations Forces: 1996 Kangnung Specialist Angiene L. Myers Submarine Infiltration Cover Photographs: by Major Harry P. Dies, Jr. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Cover Design: 35 Deconstructing The Theory of 4th Generation Warfare Specialist Angiene L. Myers by Del Stewart, Chief Warrant Officer Three (Retired) Purpose: The U.S. Army Intelli- gence Center and Fort Huachuca (USAIC&FH) publishes the Military DEPARTMENTS Intelligence Professional Bulle- tin quarterly under provisions of AR 2 Always Out Front 58 Language Action 25-30. MIPB disseminates mate- rial designed to enhance individu- 3 CSM Forum 60 Professional Reader als’ knowledge of past, current, and emerging concepts, doctrine, materi- 4 Technical Perspective 62 MIPB 2004 Index al, training, and professional develop- ments in the MI Corps. -

For Royal Navy, Army

Ministry of Defence Main Building Whitehall London SW1A 2HB United Kingdom Telephone : XXXXXXXXXXXXXX Our Reference: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXX xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxx Dear XXXXXXXX, Thank you for your e-mail to the Ministry of Defence (MOD) dated XXXXXXX in which you requested the following information: Please provide figures:- Regular RN RAF and Army other ranks (ratings) who have disclosed educational degrees. I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOI) 2000. A review of our data holdings has been completed, and I can confirm that the MOD does hold some information within the scope of your request; this is provided in the attached Annex. If you are not satisfied with this response or you wish to complain about any aspect of the handling of your request, then you should contact me in the first instance. If informal resolution is not possible and you are still dissatisfied then you may apply for an independent internal review by contacting the Information Rights Compliance team, 1st Floor, MOD Main Building, Whitehall, SW1A 2HB (e-mail [email protected]). Please note that any request for an internal review must be made within 40 working days of the date on which the attempt to reach informal resolution has come to an end. If you remain dissatisfied following an internal review, you may take your complaint to the Information Commissioner under the provisions of Section 50 of the Freedom of Information Act. Please note that the Information Commissioner will not investigate your case until the MOD internal review process has been completed. -

Lieutenant Colonel Donyeill (Don) A. Mozer US Army, Regular Army Cell

Lieutenant Colonel Donyeill (Don) A. Mozer U.S. Army, Regular Army Cell: 785-375-6055 [email protected] or [email protected] Objective Complete Doctorate in Interdisciplinary Health Sciences at University of Texas at El Paso. Summary of Personal Qualifications Donyeill “Don” Mozer is a career Army officer with 20 years of active duty leadership experience in the US Army. He additionally has 5 years of prior service as an enlisted Soldier in the US Army Reserves. He was able to overcome an adverse childhood to become a successful leader in the military. He has held numerous leadership and staff officer positions throughout his career and has extensive operational and combat experience through deployments to Afghanistan, Iraq, Kuwait, and South Korea. Donyeill Mozer also spent two years teaching military science at the United States Military Academy and was The Army ROTC Department Head and Professor of Military Science at McDaniel College in Westminster, MD (which also included the ROTC programs at Hood College and Mount Saint Mary’s University. LTC Mozer earned a BA degree in Sociology from University of North Carolina at Charlotte and Masters in Public Administration from CUNY John Jay College. His military education includes the Infantry Basic Officers Leaders Course, Logistics Captains Career Course, Airborne School, Ranger School, and Intermediate Level Education. In 2011, he participated in a summer program where he studied genocide prevention in Poland with the University of Krakow. Civilian Education City University of New York at John Jay College MPA – Public Administration 2009 NYC, New York University of North Carolina at Charlotte B.A. -

The Active-Duty Officer Promotion and Command Selection Processes

Issue Paper #34 Promotion Version 3 The Active-Duty Officer Promotion and Command Selection Processes Considerations for Race/Ethnicity and Gender MLDC Research Areas 1 Definition of Diversity Abstract gender. The MLDC in turn requested that the military Services and the Coast Guard Legal Implications Two MLDC charter tasks directed the com- describe their promotion and command selec- Outreach & Recruiting missioners to evaluate whether the officer tion processes so that the MLDC could study promotion and command selection systems whether certain features of these systems Leadership & Training provide fair opportunities to both men and might affect the selection of officers based on Branching & Assignments women and members of all race/ethnicity their race/ethnicity or gender. A summary of groups. Using Service briefings and other the presentations from the fall 2009 and win- Promotion information provided to the MLDC, this ter 2010 MLDC meetings, along with relevant Retention Issue Paper (IP) describes key features of material provided by the Services after the meetings, is presented.2 Implementation & the promotion and command selection proc- Accountability esses and discusses how they may accentu- There are three main ways in which ate or mitigate the potential for bias in the promotion and command opportunities may Metrics selection of officers for promotion or com- be unfair. First, a lack of fairness may develop National Guard & Reserve mand. Overall, the promotion and command before officers are actually evaluated for selection board processes include a number promotion or command selection; this occurs of features that attempt to impart fairness if race/ethnicity or gender affects the assign- and to mitigate the impact of bias on the ment of officers to key positions that enhance part of an individual board member. -

28 Subpart H—The Commanding Officer

§ 700.720 32 CFR Ch. VI (7–1–13 Edition) or chief staff officer while he or she is Personnel, as appropriate, of such ac- executing the duties of that office. tion. (b) The officers of a staff shall be re- (b) If the designating commander de- sponsible for the performance of those sires the commanding officer of staff duties assigned to them by the com- enlisted personnel to possess authority mander and shall advise the com- to convene courts-martial, the com- mander on all matters pertaining mander should request the Judge Advo- thereto. In the performance of their cate General to obtain such authoriza- staff duties they shall have no com- tion from the Secretary of the Navy. mand authority of their own. In car- rying out such duties, they shall act § 700.723 Administration and dis- for, and in the name of, the com- cipline: Separate and detached mander. command. Any flag or general officer in com- ADMINISTRATION AND DISCIPLINE mand, any officer authorized to con- vene general courts-martial, or the § 700.720 Administration and dis- senior officer present may designate cipline: Staff embarked. organizations which are separate or de- In matters of general discipline, the tached commands. Such officer shall staff of a commander embarked and all state in writing that it is a separate or enlisted persons serving with the staff detached command and shall inform shall be subject to the internal regula- the Judge Advocate General of the ac- tions and routine of the ship. They tion taken. If authority to convene shall be assigned regular stations for courts-martial is desired for the com- battle and emergencies. -

Fm 3-21.5 (Fm 22-5)

FM 3-21.5 (FM 22-5) HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY JULY 2003 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. *FM 3-21.5(FM 22-5) FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS No. 3-21.5 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY WASHINGTON, DC, 7 July 2003 DRILL AND CEREMONIES CONTENTS Page PREFACE........................................................................................................................ vii Part One. DRILL CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1. History................................................................................... 1-1 1-2. Military Music....................................................................... 1-2 CHAPTER 2. DRILL INSTRUCTIONS Section I. Instructional Methods ........................................................................ 2-1 2-1. Explanation............................................................................ 2-1 2-2. Demonstration........................................................................ 2-2 2-3. Practice................................................................................... 2-6 Section II. Instructional Techniques.................................................................... 2-6 2-4. Formations ............................................................................. 2-6 2-5. Instructors.............................................................................. 2-8 2-6. Cadence Counting.................................................................. 2-8 CHAPTER 3. COMMANDS AND THE COMMAND VOICE Section I. Commands ........................................................................................ -

Organization of the Roman Military 150 CE

Organization of the Roman Military 150 CE It was the strength and proficiency of the Roman army that held the empire together against internal revolts and threats from beyond the borders. The army was unique in the classical world: a professional standing army, with state-provided weapons and armor, salaried troops, and 30 or so legions (the main body of the army) permanently stationed at garrison towns along imperial frontiers. Legions were reinforced with auxiliary troops drawn from the local population. To support the army and protect merchant shipping from piracy, Rome maintained a large navy with fleets in the Mediterranean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean, and along the Rhine and Danube Rivers. LEGION UNITS Legion A body of about 5,000 foot soldiers, uniformly legionaries (160 in first cohort centuries). There were 6 trained and equipped—similar to a modern army division. centuries in the 2nd to 10th cohorts and 5 in the first A legion was the smallest formation in the Roman army cohort. capable of sustained independent operations. Cavalry A small force of about 120 mounted legionaries Cohort (10) The distinct tactical units of a legion, each attached to each legion for escort, messenger, and about 480 men strong—equivalent in size and function to reconnaissance duties. They were not usually seen on a modern infantry battalion. The first cohort was the battlefield. approximately double strength (around 800 men) and Artillery Each legion had 60 engines (catapults). One contained the best soldiers. engine was capable of shooting yard-long, heavy bolts Century (59) An administrative unit within a cohort. -

Revised Tri Ser Pen Code 11 12 for Printing

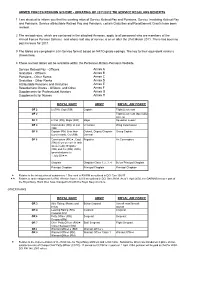

ARMED FORCES PENSION SCHEME - UPRATING OF 2011/2012 TRI SERVICE REGULARS BENEFITS 1 I am directed to inform you that the existing rates of Service Retired Pay and Pensions, Service Invaliding Retired Pay and Pensions, Service attributable Retired Pay and Pensions, certain Gratuities and Resettlement Grants have been revised. 2 The revised rates, which are contained in the attached Annexes, apply to all personnel who are members of the Armed Forces Pension Scheme and whose last day of service is on or after the 31st March 2011. There has been no pay increase for 2011. 3 The tables are compiled in a tri-Service format based on NATO grade codings. The key to their equivalent ranks is shown here. 4 These revised tables will be available within the Personnel-Miltary-Pensions Website. Service Retired Pay - Officers Annex A Gratuities - Officers Annex B Pensions - Other Ranks Annex C Gratuities - Other Ranks Annex D Attributable Pensions and Gratuities Annex E Resettlement Grants - Officers, and Other Annex F Supplements for Professional Aviators Annex G Supplements for Nurses Annex H ROYAL NAVY ARMY ROYAL AIR FORCE OF 2 Lt (RN), Capt (RM) Captain Flight Lieutenant OF 2 Flight Lieutenant (Specialist Aircrew) OF 3 Lt Cdr (RN), Major (RM) Major Squadron Leader OF 4 Commander (RN), Lt Col Lt Colonel Wing Commander (RM), OF 5 Captain (RN) (less than Colonel, Deputy Chaplain Group Captain 6 yrs in rank), Col (RM) General OF 6 Commodore (RN)«, Capt Brigadier Air Commodore (RN) (6 yrs or more in rank (preserved)); Brigadier (RM) and Col (RM) (OF6) (promoted prior to 1 July 00)«« Chaplain Chaplain Class 1, 2, 3, 4 Below Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain « Relates to the introduction of substantive 1 Star rank in RN/RM as outlined in DCI Gen 136/97 «« Relates to rank realignment for RM, effective from 1 Jul 00 as outlined in DCI Gen 39/99. -

This Index Lists the Army Units for Which Records Are Available at the Eisenhower Library

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. ARMY: Unit Records, 1917-1950 Linear feet: 687 Approximate number of pages: 1,300,000 The U.S. Army Unit Records collection (formerly: U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater: Selected After Action Reports, 1941-45) primarily spans the period from 1917 to 1950, with the bulk of the material covering the World War II years (1942-45). The collection is comprised of organizational and operational records and miscellaneous historical material from the files of army units that served in World War II. The collection was originally in the custody of the World War II Records Division (now the Modern Military Records Branch), National Archives and Records Service. The material was withdrawn from their holdings in 1960 and sent to the Kansas City Federal Records Center for shipment to the Eisenhower Library. The records were received by the Library from the Kansas City Records Center on June 1, 1962. Most of the collection contained formerly classified material that was bulk-declassified on June 29, 1973, under declassification project number 735035. General restrictions on the use of records in the National Archives still apply. The collection consists primarily of material from infantry, airborne, cavalry, armor, artillery, engineer, and tank destroyer units; roughly half of the collection consists of material from infantry units, division through company levels. Although the collection contains material from over 2,000 units, with each unit forming a separate series, every army unit that served in World War II is not represented. Approximately seventy-five percent of the documents are from units in the European Theater of Operations, about twenty percent from the Pacific theater, and about five percent from units that served in the western hemisphere during World War II.