The Woodworker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Things You Should Know About Your Chainsaw

Things You Should Know About Your Chainsaw Having a sharp blade on a chainsaw the chain link. The curve of the file should not only saves effort and wear on your fit the curve of the face of the cutting tip, Tips equipment, but makes using it more safe. and the top of the file should be nearly Here are some tips for sharpening your flush with the top of the tooth. • Buy the correct size file for your saw. own saw. Hold the file at the same angle that the • It is recommended that after a chain has been hand sharpened five times, it should be 1) Determine the size or gauge of your cutter is ground or filed to begin with. The ground by a chainsaw shop to correct any saw's chain. You will need to buy either a standard angle is about 25 degrees on variations in tooth pitch that occurred during rotary grindstone or chainsaw file/rattail most saws. Special "ripping" chains may filing. file that matches your blade. Since there • Use a chainsaw file guide to maintain have a flatter angle, and it is essential to the correct angle of your file stroke when fil- are several sizes of chainsaw teeth, the match the angle the chain is originally ing your blade. grindstone or file you choose must be the machined to. • Look for wear on the drive links, the correct diameter for your saw. Typical 7) Slide the file across the face of the blade groove, and sprocket often. Chains can break and cause serious injury or death when sizes are 3/16, 5/32 and 7/32 inches in cutter, using a moderate twisting motion operated with worn or damaged parts. -

Dualmaster 3000 Manual

DUALMASTER 3000 MANUAL DUALMASTER 3000 Precision Reel/Cylinder Spin & Relief Grinder ISSUE ONE — Serial No. 22110 – on User’s Guide & Instruction Manual Please read this manual carefully before using the Dual Master. This manual should be kept in a safe place so that it can be used for future reference. DUAL MASTER 3000 NOTES ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Lumber and Related Products; a Base Syllabus on Wood Technology. Eastern Kentucky Univ., Richmond

4-f,r ' DOCUMENT RESUME ED 031 558 VT 007 859 Lumber and Related Products; A Base Syllabus on Wood Technology. Eastern Kentucky Univ., Richmond. Pub Date Aug 68 Note-108p.; From NDEA Inst. on Wood Technology (Eastern Kentucky UM, June 10-Aug. 2, 1968). EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC-$5.50 Descriptors-*Building Materials, Curriculum Development, *Curriculum Guides, *Industrial Arts, Instructional Improvement, Lumber Industry, *Resource Materials, Summer Institutes, Teacher Developed Materials, Teacher Education, *Woodworking Identifiers-*National Defense Education Act Title XI Institute, NDEA Title XI Institute Prepared by participants in the 1%8 National Defense Education Act Institute on Wood Technology, this syllabus is one of a seriesof basic outlines designed to aid college level industrial arts instructors in improving and broadening the scope and .content of their programs. The primary objective of this course outhne is to point out the importance and the many uses of wood and wood products. Topics covered are: (1 )Lumber Grades and Sizes,(2)Plywood,(3)Veneer,(4)Fiberboard,(5) Particleboard,(6)Sheetboard,(7)InsulationBoard,(8)StructuralSandwich Construction,(9)Shingles,(10)Pulp and Paper,(11) Wood Flour,and (12) Cellulose-DerivedProducts.Mostunitscontain 'informationonmanufacturing processes, properties,types and grades, and uses of the products. Selected bibliographies are listed for each unit. The final section provides instructional aids, suggested projects and student activities, and materials and equipment needed for specific prolects. The document is &strafed with drawings, charts, and photographs. Related documents are available as VT 007 857, VT 007 858, and VT 007 861: (AW) ft; LUMBER BAS YLLABUS ON WOOD CHNOLOGY .:'Pre,pare4 by INSTITUTE. -

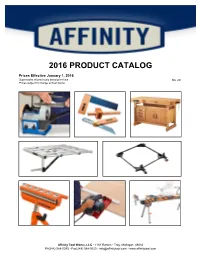

2016 Affinity Tool Works Dealer Price Book Rev 20 Xlsx

2016 PRODUCT CATALOG Prices Effective January 1, 2016 Supersedes all previously dated price lists. No. 20 Prices subject to change without notice. Affinity Tool Works, LLC • 1161 Rankin • Troy, Michigan 48083 Ph(248) 588-0395 • Fax(248) 588-0623 • [email protected] • www.affinitytool.com Pkg www.boratool.com Stock No. Description Part No. List Price Qty BORA Clamps & Vises 540445 4.5" Micro Bar Clamp (2-Pack) 6$ 10.91 540606-S 6" Midi Pistol Grip Clamp 6$ 12.64 540606 6" Midi Pistol Grip Clamp (2-Pack) 6$ 23.64 540612-S 12" Midi Pistol Grip Clamp 6$ 15.45 540612 12" Midi Pistol Grip Clamp (2-Pack) 6$ 30.00 540806 6" Pistol Grip Bar Clamp 6$ 19.09 540812 12" Pistol Grip Bar Clamp 6$ 20.91 540818 18" Pistol Grip Bar Clamp 6$ 28.18 540824 24" Pistol Grip Bar Clamp 6$ 30.00 BORA Specialized Clamps & Vises 540520 20 Piece Mini Spring Clamp Set 1$ 10.00 551025 Corner Clamp 6$ 30.00 551027 Large Vise 6$ 30.00 BORA Angle Master Miter Duplicator for Mitersaws 530301 Angle Master - Miter Duplicator 3$ 65.45 BORA Sharpening Stones 501057 Sharpening Stone-Aluminum Oxide 6" x 2" x 1" 30$ 4.47 501098 Sharpening Stone-Green Silicon Oxide 6" x 2" x 1" 30$ 8.73 501060 Sharpening Stone-Aluminum Oxide 8" x 2" x 1" 30 $ 8.90 Page 2 © 2016 Affinity Tool Works, LLC Pkg Stock No. Description List Price Qty BORA Modular Clamp Edge & Accessories 543100 100" WTX Clamp Edge (50" + 50") 6$ 99.00 543050 50" WTX Clamp Edge 6$ 53.00 543036 36" WTX Clamp Edge 6$ 46.00 543024 24" WTX Clamp Edge 6$ 40.00 Kits: 543300 3 pc Clamp Edge Set, 24, 36, 50" 4$ 134.00 543400 -

The Effects of Level of Goal Evaluation on Mood And

KEEPING YOUR EYES ON THE PRIZE VERSUS YOUR NOSE TO THE GRINDSTONE: THE EFFECTS OF LEVEL OF GOAL EVALUATION ON MOOD AND MOTIVATION ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ___________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ by LINDA HOUSER-MARKO Dr. Kennon Sheldon, Dissertation Supervisor AUGUST 2007 © Copyright by Linda Houser-Marko 2007 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate school, have examined the dissertation entitled KEEPING YOUR EYES ON THE PRIZE OR YOUR NOSE TO THE GRINDSTONE: THE EFFECTS OF LEVEL OF GOAL EVALUATION ON MOOD AND MOTIVATION presented by Linda Houser-Marko a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ___________________________________ Kennon Sheldon, PhD ___________________________________ Lynne Cooper, PhD ___________________________________ Laura King, PhD ___________________________________ Anna Bardone-Cone, PhD ___________________________________ Vicki Conn, PhD Many thanks go to my dear husband Shaun who has supported me in so many ways throughout this process. Thanks as well to my parents Bob and Betsy who always expected the best from me. And most of all, this dissertation is dedicated to my two young daughters, Claire Charlotte and Maggie Belle, who inspire me with their boundless energy. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge all those who have helped with my academic research. First I would like to thank Professor Ken Sheldon for his advice, guidance, support and patience in this long endeavor. I would also like to thank all of my committee members for their guidance, patience and support throughout the years, for both my master’s thesis project and this dissertation project. -

Wetstone Sharpener TWS S10

Wetstone Sharpener TWS S10 Fitted with a superlative, high grade diamond grindstone and leather honing wheel, the Triton Wetstone Sharpener produces a polished, razor-sharp edge on cutting and shaping tools. Used in conjunction with the supplied honing compound, the leather honing wheel delivers a finely polished finish, ideal for hand tools, knives, plane irons, chisels, and other wood carving tools. Edges won’t overheat or lose their sharpness due to the water-cooled, slow speed of the Wetstone Sharpener. Using the support arm, angle guide and jig, it is easy to shape and sharpen a blade precisely to the angle required. Pre-dressed and ready for use, the high-grade diamond grindstone can be easily and quickly re-dressed with the provided stone grader. The 120W / 1A induction motor provides long-lasting, smooth performance and rubber feet keep the machine steady and minimise vibration for a perfect finish. Large Handle for easy carrying Horizontal Mounts for Support Arm to maintain the correct angle for honing the blade High-Grade Diamond Grindstone sharpens steel edges efficiently Vertical Mounts for & reliably Support Arm for perfect positioning of the blade for sharpening Water Trough keeps the stone wet & the grinding surface cool, preventing overheating Leather Honing Wheel for a razor-sharp, polished edge Rubber Feet keep the machine steady Smooth 120W / 1A & minimise vibration Induction Motor provides quiet & efficient operation Selling Points Optional Accessories • High grade, pre-dressed diamond grindstone with stone grader -

EC702 Grinding the Farm Tools

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension Extension 4-1938 EC702 Grinding the Farm Tools L. M. Roehl Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Roehl, L. M., "EC702 Grinding the Farm Tools" (1938). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska- Lincoln Extension. 2186. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/2186 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AG'(!.J_ ~ El Extension Circular 702 April i938 w{O;;) Grinding the Farm Tools L. M. Roehl A reprint of a bull etin originall y prepared fo r and published by the NEw YoRK STATE CoLLEGE oF AGRICULTURE CORNELL N IVERSITY, I THACA, N. Y . THE :-J IVERSITY OF .'-JEBRASKA AGRICULTURAL CoLLEGE ExTENSio , SERVICE AND THE N ITED STATES D EPARTMENT OF AGR ICULT RE, COOPERATING w. H . BROKAW, D!RECT OR , L t:" CO L:'\ CORNELL EXTENSIO BULLETIN PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AT CORNELL UNIVERSITY, ITHACA, NEW YORK CARL E. LADD, DEAN OF T H E COLLEGE L. R. S IMONS, DIRECTOR OF EXTEN SION SERVICE EDITORS FOR THE COLLEGE BRISTOW ADA~I S NELL B. LEONARD GRINDING THE FARM TOOLS L. M. RoEHL UCCE~SFUL work and pleasure in the use of tools depend largely on their condition. This bulletin has been written to help those who S grind their own tools. -

Handtools for Trail Work Forest Service

United States In cooperation Department of with Agriculture Handtools for Trail Work Forest Service Technology & 2005 Edition Development Program 2300 Recreation February 2005 0523–2810P–MTDC You can order a copy of this document using the order form on the FHWA’s Recreational Trails Program Web site Notice at <http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/rectrails/trailpub .htm>. This document was produced in cooperation with the Recreational Trails Program of the U.S. Department of Fill out the order form and submit it electronically. Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government Or you may email your request to: assumes no liability for the use of information contained in [email protected] this document. Or mail your request to: The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manu- Szanca Solutions/FHWA PDC facturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in 13710 Dunnnings Highway this report only because they are considered essential to Claysburg, PA 16625 the objective of this document. Fax: 814–239–2156 The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, Produced by: who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data USDA Forest Service, MTDC presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect 5785 Hwy. 10 West the official policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. Missoula, MT 59808-9361 This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or Phone: 406–329–3978 regulation. Fax: 406–329–3719 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.fs.fed.us/eng/pubs —Cover photo: The 1924 Trail Gang in the Flume, Courtesy of the Appalachian Mountain Club. -

No. 327,758, Patented Oct. 6, 1885

(Model.) 2. Sheets-Sheet 1. J. BIRKENHEAD, MECHANISM FOR SUPPORTING AND GUIDING DRILLS WHILE BEING GROUND, No. 327,758, Patented Oct. 6, 1885, sn s N, pers. Plato-Liaographer, Washington, , . (Model.) 2 sheets-sheet 2. J. BIRKENHEAD. MECHANISM FOR SUPPORTING AND GUIDING DRILLS WHILE BEING GROUND. No. 327,758. Patented 00t, 6, 1885, Z2 (erve fres. 77vez for (2 M. C24 e/a/.7z Azréezz/eagé, N, PETERs, Photo-Lithographer, Washington, C. C. UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. JOHN B I. R. KEN HEAD, OF MANS FIELD, MASS ACHU SETTS. MECHANISM FOR SUPPORTNG AND GUIDING DRILLS WHILE BEING GROUND, S321:CIEICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 327,758, dated October 6, 1885. Application filed September 19, 1883. Serial No. 106,796. (Model.) To a 2Z Zuhon, it inval/ conce772, : prevent end wise motion of Said journal in its Be it known that I, JoHNBIRKENHEAD, of bearing. This bearing f has a journal, h, ex Mansfield in the county of Bristol, of the tending down from it into a post, i, also made Commonwealth of Massachusetts, have invent so as to be capable of being clamped to the ed a new and useful Improvement in Mech journal by a screw, k. This post extends up anism for Supporting and Guiding a Twist or ward from a base, l, having appliances for fiX Angularly Pointed Drill while in the act of ing it on the trough of a grindstone in a being Sharpened by a Grindstone; and I do manner to enable the tool-rest to be brought hereby declare the same to be described in the into a suitable position relatively to the stone following specification and represented in the for a drill to be ground or sharpened thereby. -

Get Top Results with a Real Sharpening System

NEW DESIGN CAST FRAME FOR MAXIMUM PRECISION Tormek Jig Solutions Included with the Tormek T-8 SVM-45 Knife Jig SE-77 Square Edge Jig For most knives. Jig width 45 mm For plane irons and wood chisels. (1¾"). Long knives need to be stiff. Max tool width 77 mm (3"), max tool Minimum blade length 60 mm (23/8"). Get top results with thickness 9 mm (3/8"). Safety stops prevent Also for carver’s draw knives. the tool from slipping off the stone. UPGRADED (SE-77 replaces SE-76.) For small knives see SVM-00 under Accessories a real sharpening system SVM-140 TT-50 Truing Tool Long Knife Jig Trues the grindstone exactly round and Suitable for long and flexible knives. flat. Guided by the Universal Support, The 140 mm (5½") width of the jig which also guides the jigs. Dual knobs stabilizes a thin blade. Minimum for smooth feed across the stone. blade length 160 mm (6¼"). SVX-150 SP-650 Stone Grader Scissors Jig Square The fine side grades the stone for a 1000 Universal Support For scissors of all sizes and shears. Edge Jig grit finish. The coarse side of the grader • For vertical or horizontal mount. Also suitable for portable electric Dimensions reverses the stone to normal fast grinding. • Micro adjust with scale for each 0.25 mm (0.01"). hand planer blades. Width 270 mm (105/8") Activates a glazed stone. Depth 270 mm (105/8") Height 330 mm (12") SVA-170 Axe Jig Leather Honing Wheel Weight WM-200 AngleMaster For carving and carpenter’s axes. -

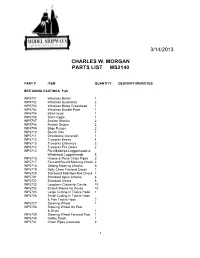

3/14/2013 Charles W. Morgan Parts List Ms2140

3/14/2013 CHARLES W. MORGAN PARTS LIST MS2140 PART # ITEM QUANTITY DESCRIPTION/NOTES BRITANNIA CASTINGS 9 pk WP5701 Windlass Barrel 1 WP5702 Windlass Quadrants 2 WP5703 Windlass Brake Crosshead 1 WP5704 Windlass Double Pawl 1 WP5705 Billet Head 1 WP5706 Stern Eagle 1 WP5707 Anchor Shanks 2 WP5708 Anchor Stocks 2 WP5709 Bilge Pumps 2 WP5710 Bench Vise 1 WP5711 Grindstone (covered) 1 WP5712 Tryworks Knees 4 WP5713 Tryworks Chimneys 2 WP5714 Tryworks Fire Doors 2 WP5715 Port Midships Loggerheads & Whaleboat Loggerheads 6 WP5716 Hawse & Fluke Chain Pipes 3 WP5717 Forward Round Mooring Chock 2 WP5718 Oblong Mooring Chocks 6 WP5719 Belly Chain Fairlead Chock 1 WP5720 Starboard Midships Rail Chock 1 WP5721 Standard Open Chocks 8 WP5722 Standard Cleats 8 WP5723 Longhorn Cleats for Davits 10 WP5724 Snatch Blocks for Davits 10 WP5725 Large Cutting-In Tackle Hook 1 WP5726 Small Cutting-In Tackle Hook & Fish Tackle Hook 2 WP5727 Steering Wheel 1 WP5728 Steering Wheel Aft Post & Drum 1 WP5729 Steering Wheel Forward Post 1 WP5730 Galley Stack 1 WP5731 Chain Pipes (covered) 2 1 WP5732 Mainmast Fife Rail Stanchions 3 WP5733 Fore & Main Lower Yard Truss 2 WP5734 Fore & Main Topsail Iron Sheet Blocks 2 WP5735 Fore & Main Upper Topsail Fixed Truss & Bands 2 WP5736 Fore & Main Lower Topsail Parrel Tub & Truss 2 WP5737 Fore & Main Spider Bands 2 WP5738 Mizzen Spider Band 1 WP5739 Large Whaleboat Line Tubs 5 WP5740 Small Whaleboat Line Tubs 5 WP5741 Tryworks Pots Male (half) 2 WP5742 Tryworks Pots Female (half) 2 WP5743 Running Lights 2 BRASS AND MISCELLANEOUS FITTINGS AND MATERIAL WP0411 Belaying Pins 150 WP0429 Small Eyebolts 200 WP0428 Large Eyebolts 30 WP0955 1/8" Split Rings 40 WP0888 1/64" x 1/16" Strip 4 ft WP40285SEC 0.010" Dia. -

Safety Sheet 11 – Grinding Machinery

Bureau de la gestion du risque | Office of Risk Management 139, Louis-Pasteur (pièce 265) | 139 Louis Pasteur (Room 265) Safety Sheet 11 – Grinding Machinery Consult the Ontario Occupational Health and Safety Act and its Regulations, more specifically the Industrial Establishments – Regulation 851, as well as the relevant CSA Standard for detailed information on grinding machinery. A grinding wheel is defined as an expendable wheel that carries an abrasive compound on its border; generally made from a matrix of coarse particles pressed and bonded together to form a solid, circular shape. A ring test (also referred to as an acoustic test) is a method to check if the wheel is in proper working order. To conduct the test, hold the grindstone by its centre and lightly tap the grindstone in four opposite corners with a non-metallic object (wooden mallet, plastic-handled screwdriver) and listen at every tap; a clear (metallic “ring”) sound indicates a solid grindstone while a muffled (dead) sound indicates the grindstone is cracked; see “How to conduct a ring test”. Any wheel that is cracked should be discarded. A competent person is defined by the Ontario Occupational Health & Safety Act as a person who (i) is qualified because of knowledge, training and experience to organize the work and its performance; (ii) is familiar with this Act and the regulations that apply to the work and (iii) has knowledge of any potential or actual danger to health & safety in the workplace. Hazard classes: Mechanical – abrasions, contusions and fractures can