A Structural Analysis of George Enescu's Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2014-2015

27 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, May 7, at 8:00 Friday, May 8, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, May 9, at 8:00 Cristian Măcelaru Conductor Sarah Chang Violin Ligeti Romanian Concerto I. Andantino— II. Allegro vivace— III. Adagio ma non troppo— IV. Molto vivace First Philadelphia Orchestra performances Beethoven Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21 I. Adagio molto—Allegro con brio II. Andante cantabile con moto III. Menuetto (Allegro molto e vivace)—Trio— Menuetto da capo IV. Adagio—Allegro molto e vivace Intermission Dvořák Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53 I. Allegro ma non troppo—Quasi moderato— II. Adagio ma non troppo—Più mosso—Un poco tranquillo, quasi tempo I III. Finale: Allegro giocoso ma non troppo Enescu Romanian Rhapsody in A major, Op. 11, No. 1 This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. The May 7 concert is sponsored by MedComp. The May 8 and 9 concerts are sponsored by the Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation. designates a work that is part of the 40/40 Project, which features pieces not performed on subscription concerts in at least 40 years. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 228 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world, renowned for its distinctive sound, desired for its keen ability to capture the hearts and imaginations of audiences, and admired for a legacy of imagination and innovation on and off the concert stage. -

Diatonic-Collection Disruption in the Melodic Material of Alban Berg‟S Op

Michael Schnitzius Diatonic-Collection Disruption in the Melodic Material of Alban Berg‟s Op. 5, no. 2 The pre-serial Expressionist music of the early twentieth century composed by Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils, most notably Alban Berg and Anton Webern, has famously provoked many music-analytical dilemmas that have, themselves, spawned a wide array of new analytical approaches over the last hundred years. Schoenberg‟s own published contributions to the analytical understanding of this cryptic musical style are often vague, at best, and tend to describe musical effects without clearly explaining the means used to create them. His concept of “the emancipation of the dissonance” has become a well known musical idea, and, as Schoenberg describes the pre-serial music of his school, “a style based on [the premise of „the emancipation of the dissonance‟] treats dissonances like consonances and renounces a tonal center.”1 The free treatment of dissonance and the renunciation of a tonal center are musical effects that are simple to observe in the pre-serial music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, and yet the specific means employed in this repertoire for avoiding the establishment of a perceived tonal center are difficult to describe. Both Allen Forte‟s “Pitch-Class Set Theory” and the more recent approach of Joseph Straus‟s “Atonal Voice Leading” provide excellently specific means of describing the relationships of segmented musical ideas with one another. However, the question remains: why are these segmented ideas the types of musical ideas that the composer wanted to use, and what role do they play in renouncing a tonal center? Furthermore, how does the renunciation of a tonal center contribute to the positive construction of the musical language, if at all? 1 Arnold Schoenberg, “Composition with Twelve Tones” (delivered as a lecture at the University of California at Las Angeles, March 26, 1941), in Style and Idea, ed. -

Roots & Origins

Sunday 16 December 2018 7–9.15pm Tuesday 18 December 2018 7.30–9.45pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT ROOTS & ORIGINS Brahms Violin Concerto Interval ROMANIAN Debussy Images Enescu Romanian Rhapsody No 1 Sir Simon Rattle conductor Leonidas Kavakos violin These performances of Enescu’s Romanian Rhapsody No 1 are generously RHAPSODY supported by the Romanian Cultural Institute 16 December generously supported by LSO Friends Welcome Latest News On Our Blog We are grateful to the Romanian Cultural BRITISH COMPOSER AWARDS MARIN ALSOP ON LEONARD Institute for their generous support of these BERNSTEIN’S CANDIDE concerts. Sunday’s concert is also supported Congratulations to LSO Soundhub Associate by LSO Friends, and we are delighted to have Liam Taylor-West and LSO Panufnik Composer Marin Alsop conducted Bernstein’s Candide, so many Friends with us in the audience. Cassie Kinoshi for their success in the 2018 with the LSO earlier this month. Having We extend our thanks for their loyal and British Composer Awards. Prizes were worked closely with the composer across important support of the LSO, and their awarded to Liam for his Community Project her career, Marin drew on her unique insight presence at all our concerts. The Umbrella and to Cassie for Afronaut, into Bernstein’s music, words and sense of a jazz composition for large ensemble. theatre to tell us about the production. I wish you a very happy Christmas, and hope you can join us again in the New Year. The • lso.co.uk/more/blog elcome to this evening’s LSO LSO’s 2018/19 concert season at the Barbican FELIX MILDENBERGER JOINS THE LSO concert at the Barbican. -

Citymac 2018

CityMac 2018 City, University of London, 5–7 July 2018 Sponsored by the Society for Music Analysis and Blackwell Wiley Organiser: Dr Shay Loya Programme and Abstracts SMA If you are using this booklet electronically, click on the session you want to get to for that session’s abstract. Like the SMA on Facebook: www.facebook.com/SocietyforMusicAnalysis Follow the SMA on Twitter: @SocMusAnalysis Conference Hashtag: #CityMAC Thursday, 5 July 2018 09.00 – 10.00 Registration (College reception with refreshments in Great Hall, Level 1) 10.00 – 10.30 Welcome (Performance Space); continued by 10.30 – 12.30 Panel: What is the Future of Music Analysis in Ethnomusicology? Discussant: Bryon Dueck Chloë Alaghband-Zadeh (Loughborough University), Joe Browning (University of Oxford), Sue Miller (Leeds Beckett University), Laudan Nooshin (City, University of London), Lara Pearson (Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetic) 12.30 – 14.00 Lunch (Great Hall, Level 1) 14.00 – 15.30 Session 1 Session 1a: Analysing Regional Transculturation (PS) Chair: Richard Widdess . Luis Gimenez Amoros (University of the Western Cape): Social mobility and mobilization of Shona music in Southern Rhodesia and Zimbabwe . Behrang Nikaeen (Independent): Ashiq Music in Iran and its relationship with Popular Music: A Preliminary Report . George Pioustin: Constructing the ‘Indigenous Music’: An Analysis of the Music of the Syrian Christians of Malabar Post Vernacularization Session 1b: Exploring Musical Theories (AG08) Chair: Kenneth Smith . Barry Mitchell (Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance): Do the ideas in André Pogoriloffsky's The Music of the Temporalists have any practical application? . John Muniz (University of Arizona): ‘The ear alone must judge’: Harmonic Meta-Theory in Weber’s Versuch . -

Chamberfest Cleveland Announces 2016 Season by Daniel Hathaway

ChamberFest Cleveland announces 2016 season by Daniel Hathaway ChamberFest Cleveland has announced its fifth season under the joint artistic direction of its founders, Cleveland Orchestra principal clarinet emeritus Franklin Cohen and his daughter, Diana Cohen, concertmaster of Canada’s Calgary Symphony. Eleven concerts over fourteen days will be held at venues throughout metropolitan Cleveland from June 16 through July 2. The theme for 2016 is “Tales and Legends.” Concerts will center around stories ranging from the profane to the divine, including the fantastical, mystical, and obsessive. Performers who will join Franklin and Diana Cohen include (to name just a few) pianists Orion Weiss and Roman Rabinovich, violinist/violist Yura Lee, violinist Noah BendixBalgley, and accordionist Merima Ključo, who is composing a piece to be premiered at the festival. The complete schedule is as follows (performers for each event will be announced later). For subscriptions and ticket information, visit the ChamberFest website. Wednesday, June 15 — Nosh at Noon at WCLV’s Smith Studio in Playhouse Square, featuring ChamberFest Cleveland’s 2016 Young Artists (free event). Thursday, June 16 at 8:00 pm — Schumann Fantasies at CIM’s Mixon Hall, 11021 East Blvd. (Openingnight party follows the performance at Crop Kitchen, 11460 Uptown Ave.) Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestucke, Movement from the “F.A.E” Sonata and Piano Quintet, Gyorgy Kurtág’s Hommage à Schumann, and Stephen Coxe’s A Book of Dreams. Friday, June 17 at 8:00 pm — To My Distant Beloved in Reinberger Chamber Hall at Severance Hall (sponsored by The Cleveland Orchestra). Frank Bridge’s Three Songs for MezzoSoprano, Antonín Dvořák’s Cypresses, Gyorgy Kurtág’s One More Voice from Far Away, Ludwig van Beethoven’s To My Distant Beloved, and Johannes Brahms’s Piano Quartet in c. -

The Glorious Violin David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors July 14–August 5, 2017

Music@Menlo CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE The Fifteenth Season: The Glorious Violin David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors July 14–August 5, 2017 REPERTOIRE LIST (* = Carte Blanche Concert) Joseph Achron (1886–1943) Hebrew Dance, op. 35, no. 1 (1913) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Chaconne from Partita no. 2 in d minor for Solo Violin, BWV 1004 (1720)* Prelude from Partita no. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006 (arr. Kreisler) (1720)* Double Violin Concerto in d minor, BWV 1043 (1730–1731) Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) String Quintet in C Major, op. 29 (1801) Violin Sonata no. 10 in G Major, op. 96 (1812) Heinrich Franz von Biber (1644–1704) Passacaglia in g minor for Solo Violin, The Guardian Angel, from The Mystery Sonatas (ca. 1674–1676)* Ernest Bloch (1880–1959) Violin Sonata no. 2, Poème mystique (1924)* Avodah (1929)* Bluegrass Fiddling (To be announced from the stage)* Alexander Borodin (1833–1887) String Quartet no. 2 in D Major (1881) Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) Horn Trio in E-flat Major, op. 40 (1865) String Quartet no. 3 in B-flat Major, op. 67 (1875)* Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) Concerto Grosso in g minor, op. 6, no. 8, Christmas Concerto (1714) Violin Sonata in d minor, op. 5, no. 12, La folia (arr. Kreisler) (1700)* John Corigliano (Born 1938) Red Violin Caprices (1999) Ferdinand David (1810–1873) Caprice in c minor from Six Caprices for Solo Violin, op. 9, no. 3 (1839) Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Petite suite for Piano, Four Hands (1886–1889) Ernő Dohnányi (1877–1960) Andante rubato, alla zingaresca (Gypsy Andante) from Ruralia hungarica, op. -

Lunchtime Concert Brought to Light Elizabeth Layton Violin Michael Ierace Piano Friday 31 July, 1:10Pm

Michael Ierace has been described as a ‘talent to watch’ and his playing as ‘revelatory’. Born and raised in Adelaide, he completed his university education through to Honours level studying with Stefan Ammer and Lucinda Collins. Michael has had much success in local and national Australian competitions including winning The David Galliver Award, The Geoffrey Parsons Award, The MBS Young Performers Award and was a major prize winner in the Australian National Piano Award. In 2009, he made his professional debut with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra in the presence of the Premier of South Australia and the Polish Ambassador. In 2007, he received the prestigious Elder Overseas Scholarship from the Adelaide University. This enabled him to move to London and study at the Royal College of Music (RCM) with Professor Andrew Ball. He was selected as an RCM Rising Star and was awarded the Hopkinson Silver medal in the RCM’s Chappell Competition. From 2010-12, he was on staff as a Junior Fellow in Piano Accompaniment. In the Royal Over-Seas League Annual Music Competition, he won the Keyboard Final and the Accompanist Prize – the only pianist in the competition's distinguished history to have received both awards. In the International Haverhill Sinfonia Soloists Competition, he took second place plus many specialist awards. Michael has performed extensively throughout London and the UK and twice at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Much sort after as an associate artist for national and international guests, Michael is currently a staff pianist at the Elder Conservatorium. Lunchtime Concert Brought to Light Elizabeth Layton violin Michael Ierace piano Friday 31 July, 1:10pm PROGRAM Also notable was his relationship with his young cousin, Sergei Rachmaninoff. -

Constantin Silvestri Conducts the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Hiviz Ltd

CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. 20 - 1 The RMA (Romanian Musical Adventure) With special thanks to: was formed to record outstanding works The Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra by Romanian composers, new and and the Musicians Union CONSTANTIN SILVESTRI David Lee, Wessex Film & Sound Archive lesser-known repertoire and well-known Raymond Carpenter and Kenneth Smith repertoire interpreted in a new light. Glen Gould, Audio restoration ABOURNEMOUTHLOVEAFFAIR 72 Warwick Gardens, London W14 8PP Georgina Rhodes and Richard Proctor, Design. Email: [email protected] Photograph of the sea, Richard Proctor The legendary Constantin Silvestri conducts the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra www.romanianmusicaladventure.org HiViz Ltd. Media Solutions, CD Production and print BBC The George Enescu Museum, Bucharest Constantin Silvestri’s BBC recordings are also available on BBC Legends www.mediciarts.co.uk © 2009 RMA, London. The BBC word mark and logo is a trade mark of the British Broadcasting Corporation and is used under license from BBC Worldwide. BBC logo © BBC 1996 2CD DIGITALLY RE-MASTERED CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. 2 - 19 Constantin Silvestri conducts the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Disc 1 69.93 Disc 2 75.73 George Enescu (1881–1955) George Enescu (1881–1955) Symphony No. 1 First Orchestral Suite 1 Assez vif et rythmé 11.17 1 Prélude à l’unisson 6.40 2 Lent 12.42 2 Menuet lent 11.13 3 Vif et vigoureux 8.53 3 Intermède 3.40 4 Vif 6.05 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) Second Orchestral Suite 4 The Magic Flute Overture 6.52 5 Ouverture 3.43 6 Sarabande 4.12 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 7 Gigue 2.29 Symphony No. -

Incantations Analytical Commentary Graham Waterhouse

Incantations Concerto da Camera for Piano and Ensemble (2015) The balance of traditional and progressive musical parameters through the concertante treatment of the piano Analytical Commentary Graham Waterhouse A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Birmingham City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2018 The Faculty of Arts, Design and Media, Birmingham City University (Royal Birmingham Conservatoire) Abstract The aim of this research project is to investigate concertante techniques in composition with reference both to traditional models and recent works in the genre, and to redefine a contemporary understanding of concertante writing in preparation for the principal work of this thesis, Incantations for Piano and Ensemble. Starting with the contradictory meanings of the word “concertare” (to compete and to unite), as well as with a fleeting, non-musical vision of combining disparate elements, I investigate diverse styles and means of combining soloist (mainly piano) and ensemble. My aim is to expand my compositional “vocabulary”, in order to meet the demands of writing a work for piano and ensemble. This involved composing supporting works, both of concerto-like nature (with more clearly defined functions of soloist and tutti), as well as chamber music (with material equally divided between the players). Part of the research was to ascertain to what extent these two apparent opposites could be combined to create a hybrid concerto/chamber music genre in which the element of virtuosity transcends the purely bravura, to embrace a common adaptability, where soloist and ensemble players are called upon to assume a variety of roles, from the accompanimental to the soloistic. -

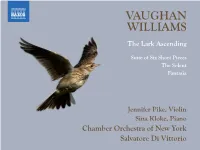

Vaughan Williams

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS The Lark Ascending Suite of Six Short Pieces The Solent Fantasia Jennifer Pike, Violin Sina Kloke, Piano Chamber Orchestra of New York Salvatore Di Vittorio Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): The Lark Ascending a flinty, tenebrous theme for the soloist is succeeded by an He rises and begins to round, The Solent · Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra · Suite of Six Short Pieces orchestral statement of a chorale-like melody. The rest of He drops the silver chain of sound, the work offers variants upon these initial ideas, which are Of many links without a break, rigorously developed. Various contrasting sections, In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake. Vaughan Williams’ earliest compositions, which date from The opening phrase of The Solent held a deep significance including a scherzo-like passage, are heralded by rhetorical 1895, when he left the Royal College of Music, to 1908, for the composer, who returned to it several times throughout statements from the soloist before the coda recalls the For singing till his heaven fills, the year he went to Paris to study with Ravel, reveal a his long creative life. Near the start of A Sea Symphony chorale-like theme in a virtuosic manner. ’Tis love of earth that he instils, young creative artist attempting to establish his own (begun in the same year The Solent was written), it appears Vaughan Williams’ mastery of the piano is evident in And ever winging up and up, personal musical language. He withdrew or destroyed imposingly to the line ‘And on its limitless, heaving breast, the this Fantasia and in the concerto he wrote for the Our valley is his golden cup many works from that period, with the notable exception ships’. -

2 1234 Couvert

CHARLES RICHARD-HAMELIN PIANO Lauréat de la médaille d’argent et du prix Krystian Originaire de la région de Lanaudière au Québec, Zimerman pour la meilleure interprétation d’une Charles Richard-Hamelin a étudié avec Paul sonate lors du Concours International de Piano Surdulescu, Sara Laimon, Boris Berman et André Frédéric-Chopin à Varsovie en 2015, Charles Laplante. Il a obtenu son diplôme de baccalauréat Richard-Hamelin se démarque aujourd’hui comme à l’Université McGill en 2011 et son diplôme de l’un des pianistes les plus importants de sa géné- maîtrise à la Yale School of Music en 2013 et a ration. Il a également obtenu le deuxième prix au reçu une bourse complète dans les deux établisse- Concours musical international de Montréal ainsi ments. Il a également obtenu un diplôme d’Artiste que le troisième prix et prix spécial pour la meil- au Conservatoire de musique et d’art dramatique leure performance d’une sonate de Beethoven au de Montréal en 2016 et a étudié auprès du pia- Seoul International Music Competition en Corée niste Jean Saulnier. Son premier album solo, du Sud. Prix d’Europe 2011 et Révélation Radio- consacré aux dernières oeuvres de Chopin, a Canada 2015-16, il fut récemment récipiendaire paru en septembre 2015 sous étiquette Analekta du prestigieux Career Development Award offert et a reçu l’éloge de critiques à travers le monde par le Women’s Musical Club of Toronto. (Diapason, BBC Music Magazine, Le Devoir). Il fut l’invité de plusieurs grands festivals tels que La Roque d’Anthéron en France, le Festival du Printemps de Prague, le Festival « Chopin et son Europe » à Varsovie et le Festival de Lanaudière (Canada). -

Ellen Rose, Viola Kristin Ditlow, Piano “There Are No Foreign Lands

AF1808 PROVIDENCE Ellen Rose, viola Kristin Ditlow, piano “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler only who is foreign.” —Robert Louis Stevenson Any listener receiving the gift of the music on this disc might assume that the musical partnership between Ellen Rose and Kristin Ditlow began somewhere in the United States, but it was quite the contrary. It began in an airport shuttle in 2011 from the Budapest Ferenc Liszt International Airport to Sárospatak, Hungary. The destination of the shuttle was the Crescendo Nyári Akademia (Crescendo Summer Institute). A conversation that began between the newly- introduced musical colleagues yielded a promise to play together on a Tune-In (informal morning chapel) service. The piece was the fifth movement of Messiaen’s Quatour pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the End of Time), and the title, Louange à l’Éternité de Jésus (Praise to the Eternity of Jesus). While this work was originally for cello and piano, it was arranged for viola by Ellen Rose. The performance took place about a week later. One of our faculty colleagues, Mari Salli (a pianist, originally from Finland, faculty member in Hungary, and working in mainland China) extended an invitation to the duo to perform during the 2012-2013 season at the National Theater in Kunming, China in the Yunnan Province. This invitation proved to be the center around which a multi-city tour was formed. From rehearsals and long-distance conversations, concerts planned, to tickets purchased, we embarked across the Pacific for a three-week tour of Beijing, Shanghai, and Kunming.