Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

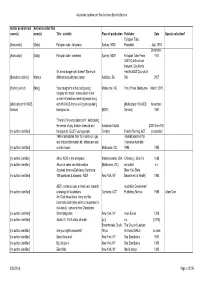

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

AM-05-Sheetmusic.Pdf

SHEET music SHEET MUSIC 27 America the Beautiful At Last (from Cadillac Records) SHEET MUSIC Words by Katherine Lee Bates, music by Samuel A. Ward Music by Harry Warren, lyric by Mack Gordon / recorded by Beyoncé Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............................$3.95 00-PVM01132____ Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............................$3.95 00-32178____ Numeric American Honey Arr. Dan Coates Words and music by Cary Barlowe, Shane Stevens, and Hillary Easy Piano ..............................................$3.95 00-32552____ 8th of November Lindsey / recorded by Lady Antebellum August Rush (Piano Suite) (from August Rush) Recorded by Big & Rich Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............................$3.99 00-34678____ Composed by Mark Mancina / arr. Dave Metzger Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............................$3.95 00-26211____ An American in Paris Advanced Piano Solo .............................$3.95 00-29201____ 21 Guns By George Gershwin / paraphrased by Maurice C. Whitney Auld Lang Syne Sheet Music Lyrics by Billie Joe, music by Green Day / recorded by Green Day / Advanced Piano Solo .............................$4.95 00-PS0004____ (from the motion picture Sex and the City) arr. Carol Matz Transcr. William Daly Traditional / arr. Mairi Campbell and Dave Francis / Easy Piano ..............................................$3.95 00-34018____ Advanced Piano Solo ...........................$14.95 00-0092B____ as recorded by Mairi Campbell and Dave Francis 10,000 Reasons (Bless the Lord) An American in Paris (Blues Theme) Piano/Vocal/Chords ...............................$3.95 00-31853____ Words and music by Matt Redman and Jonas Myrin / By George Gershwin / performance miniature transcr. and arr. Ave Maria and Prelude No. 1 recorded by Matt Redman Jan Thomas Ave Maria by Johann Sebastian Bach / Charles François Gounod, Piano/Vocal/Guitar ................................$3.99 00-39445____ Easy Piano Solo ......................................$3.50 00-PS0350____ Prelude No. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Death, Travel and Pocahontas the Imagery on Neil Young's Album

Hugvísindasvið Death, Travel and Pocahontas The imagery on Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Hans Orri Kristjánsson September 2008 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskuskor Death, Travel and Pocahontas The imagery on Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Hans Orri Kristjánsson Kt.: 260180-2909 Leiðbeinandi: Sveinn Yngvi Egilsson September 2008 Abstract The following essay, “Death, Travel and Pocahontas,” seeks to interpret the imagery on Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps. The album was released in July 1979 and with it Young was venturing into a dialogue of folk music and rock music. On side one of the album the sound is acoustic and simple, reminiscent of the folk genre whereas on side two Young is accompanied by his band, The Crazy Horse, and the sound is electric, reminiscent of the rock genre. By doing this, Young is establishing the music and questions of genre and the interconnectivity between folk music and rock music as one of the theme’s of the album. Young explores these ideas even further in the imagery of the lyrics on the album by using popular culture icons. The title of the album alone symbolizes the idea of both death and mortality, declaring that originality is transitory. Furthermore he uses recurring images, such as death, to portray his criticism on the music business and lack of originality in contemporary musicians. Ideas of artistic freedom are portrayed through images such as nature and travel using both ships and road to symbolize the importance of re-invention. -

Thesis Polygamy on the Web: an Online Community for An

THESIS POLYGAMY ON THE WEB: AN ONLINE COMMUNITY FOR AN UNCONVENTIONAL PRACTICE Submitted by Kristen Sweet-McFarling Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2014 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Lynn Kwiatkowski Cindy Griffin Barbara Hawthorne Copyright by Kristen Sweet-McFarling 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT POLYGAMY ON THE WEB: AN ONLINE COMMUNITY FOR AN UNCONVENTIONAL PRACTICE This thesis is a virtual ethnographic study of a polygamy website consisting of one chat room, several discussion boards, and polygamy related information and links. The findings of this research are based on the interactions and activities of women and men on the polygamy website. The research addressed the following questions: 1) what are individuals using the website for? 2) What are website members communicating about? 3) How are individuals using the website to search for polygamous relationships? 4) Are website members forming connections and meeting people offline through the use of the website? 5) Do members of the website perceive the Internet to be affecting the contemporary practice of polygamy in the U.S.? This research focused more on the desire to create a polygamous relationship rather than established polygamous marriages and kinship networks. This study found that since the naturalization of monogamous heterosexual marriage and the nuclear family has occurred in the U.S., due to a number of historical, social, cultural, political, and economic factors, the Internet can provide a means to denaturalize these concepts and provide a space for the expression and support of counter discourses of marriage, like polygamy. -

(Arranged) Marriage: an Autoethnographical Exploration of a Modern Practice

TCNJ JOURNAL OF STUDENT SCHOLARSHIP VOLUME XXII APRIL 2020 FIRST COMES (ARRANGED) MARRIAGE: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHICAL EXPLORATION OF A MODERN PRACTICE Author: Dian Babu Faculty Sponsor: John Landreau Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies ABSTRACT This article uses autoethnography and family interviews to analyze the modern cultural practice of arranged marriage from my standpoint as a first generation Indian-American. Borrowing from Donna Haraway’s notion of situated knowledge, Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism, and W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of double consciousness, this article presents the idea of immigrant consciousness and precedes to contend with the sociocultural circumstances, such as transnational migration, assimilation, and racism-classism, that have prompted the evolution of a modern iteration of arranged marriage. The central question that informs this paper is what does arranged marriage mean – and how can it be defended and/or criticized – in different circumstances and from different standpoints in the transnational South Asian context? INTRODUCTION Dating is foreign to me. Is that strange to hear? Let me qualify that statement: American dating is foreign to me. I am a first-generation Indian-American, Christian girl. I am the child of parents who immigrated from India to the United States and who were brought together through an arranged marriage. The practice of arranged marriage runs through most of my family history and dating is a relatively new practice to us collectively. Important to note, however, is that my family members’ individual histories, like all histories, do not run on one generalized path. I have family members who never married, who remarried, who had forced marriages, who had “love marriages,” who married young, who married non- Indian people, who divorced, and so on and so forth. -

Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage

Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage Renata Grossi Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Grossi, Renata, author. Title: Looking for love in the legal discourse of marriage / Renata Grossi. ISBN: 9781925021790 (paperback) 9781925021820 (ebook) Subjects: Marriage. Love. Marriage law. Husband and wife. Same-sex marriage. Dewey Number: 306.872 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Nic Welbourn and layout by ANU Press Cover image: Ali and David asleep 12.01am-12.31 from the Journey to Morning Series by Blaide Lallemand and Hilary Cuerden-Clifford. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction . 1 Framing the Questions of the Book . 3 The Importance of Law and Emotion Scholarship . 3 The Meaning of Love . 9 Outline of the Book . 15 1. Love and Marriage . 17 Introduction . 17 The Common Law of Marriage . 17 Nineteenth-Century Reform . 21 Twentieth-Century Reform . 23 The Meanings of Marriage: Holy Estate, Oppressive Patriarchy, Equal Love . 26 Consequences of the Love Marriage (The Feminist Critique of Love) . 31 Conclusion . 37 2. The Diminishing Significance of Sexual Intercourse . 39 Introduction . 39 The Old Discourse of Sex and Marriage . -

Saudi Sensibilities and Muslim Women's Fiction

Pakistan Journal of Women‟s Studies: Alam-e-Niswan Vol. 26, No.2, 2019, pp.19-30, ISSN: 1024-1256 LOVE, MATRIMONY AND SEXUALITY: SAUDI SENSIBILITIES AND MUSLIM WOMEN’S FICTION Muhammad Abdullah Forman Christian College University, Lahore Abstract All those desires, discriminations, success stories, and confrontations that otherwise might not have seeped into mainstream discourses are subtly said through the stories that mirror Arab women‟s lives. Girls of Riyadh is a postmodern cyber-fiction that delineates subjects we usually do not get to hear much about, i.e. the quest of heterosexual love and matrimony of young Arab women from the less women-friendly geography of Saudi Arabia. Though in the last two decades the scholarship on alternative discourses produced by Muslim women have been multitudinous, there is a scarcity of critical investigations dealing with creative constructions of postfeminist, empowered Muslim woman, not battling with patriarchal power structures, but negotiating aspects that matter most in real life: human associations and familial formations. This paper engages with the categories of love, marriage, and sexuality, drawing upon the lives of four educated, successful, „velvet class‟ Saudi women. The significance of this study is linked with carefully challenging some of the stereotypes about Arab women as victims of forced marriages and their commonly perceived discomfort with love at large. The study reveals that it is men who need to “man up” against cultural conventions since women are increasingly expressive in their choices and brave enough to face the consequences audaciously. Keywords Saudi women, Anglophone fiction, love, marriage, sexuality 20 Muhammad Abdullah Introduction Love before marriage or after? Acceding to Salafis1in some Islamic states, love is scandalized, lovers are demonized, and their associations banned. -

Understanding Child Marriage in Viet Nam Understanding Child Marriage in Viet Nam

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE empowering girls © UNICEF VIET NAM\2015\TRUONG VIET HUNG VIET NAM\2015\TRUONG VIET UNICEF © UNDERSTANDING CHILD MARRIAGE IN VIET NAM UNDERSTANDING CHILD MARRIAGE IN VIET NAM In Viet Nam, child marriage continues to be a persistent Nations held a multi-stakeholder National Conference on issue. One-in-10 Vietnamese women aged 20-24 years in Child Marriage to review gaps in policy and interventions. 2014 was found to be married or in union before their 18th In June 2017, a follow-up multi-stakeholder conference was birthday. There has been no substantial decrease in the held on “Preventing and Ending Child and Early Marriage: prevalence of child marriage. While its prevalence varies Learning from Promising Strategies and Good Practices”. across geographic areas, girls from all regions of Viet Nam and all layers of society are vulnerable to becoming a child This discussion paper builds on the outcomes of these bride. In Viet Nam, child marriage assumes different forms conferences and research on child marriage and early union and is undertaken for different reasons. To successfully in Viet Nam. It presents unique insights into the prevalence end this harmful practice, interventions must be carefully and the girls most at risk as well as the unique features tailored to local reality. and driving factors of child marriage and early union. The paper also suggests entry points for the development of In line with the UNFPA-UNICEF Global Programme to holistic and targeted interventions to prevent child mar- Accelerate Action to End Child Marriage, UNFPA and riage and early union in Viet Nam. -

Attitudes Toward Marriage and the Family Among the Unmarried Japanese Youth

Journal of Population and Social Security (Population) Vol.1 No.1 The Eleventh Japanese National Fertility Survey in 1997 Attitudes toward Marriage and the Family among the Unmarried Japanese Youth Shigesato Takahashi, Ryuichi Kaneko, Ryuzaburo Sato, Masako Ikenoue, Fusami Mita, Tsukasa Sasai, Miho Iwasawa and Yuriko Shintani (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research) Ⅰ. Overview of the Survey 1. The Purpose and History of the Survey 2. Survey Procedures and Collecting of Questionnaires Ⅱ. Marriage, a Choice - Investigating the trend among the young to avoid marriage 1. The will to marry 2. The merits of marriage and of remaining single 3. Relationships with the opposite sex 4. Why do they not marry? Ⅲ. Desirable Marriage - What kind of marriages are people looking for? 1. Desired age of marriage 2. Desirable forms of marriage 3. The attributes of the desired marriage partner 4. Desirable life course 5. The desired number of children Ⅳ. The life-style and desires of unmarried persons - Current youth profile 1. The life-style of the unmarried 2. Views related to marriage and family 1 Journal of Population and Social Security (Population) Vol.1 No.1 I. Overview of the Survey 1. The Purpose and History of the Survey The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research carried out the 11th Basic Survey on Birth Trends (a national survey on marriage and birth trends) in June 1997 (the 9th year of the Heisei era). The survey is intended to determine the actual situations and backgrounds, which cannot be found from other public statistics, of marriage and/or fertility of married couples, and to obtain the data necessary for any related measures and future population projections. -

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

APRIL 2010 Enjoyed Nationally & Internationally!

Made in Melbourne! APRIL 2010 Enjoyed Nationally & Internationally! APRIL 2010 q comment: BIRTHDAY TIME Issue 67 It delights me to announce that Q Magazine’s first issue was way back in April 2004 and that this issue Publisher & Editor Brett Hayhoe marks the beginning of our seventh year. +61 (0) 422 632 690 [email protected] I want to again thank those people (writers, contributors, advertisers, publicists and the like) who Editorial have made the ride a truly enjoyable one. Without [email protected] these incredibly generous people and YOU our loyal Sales and Marketing readers Q Magazine could not do it. [email protected] The support we have had from people throughout Design Melbourne, Australia and the world has been amazing Uncle Brett Designs & Graphics and humbling. Contributing Writers Pete Dillon, Addam Stobbs, Brett Hayhoe, I look forward to continuing to bring you Q Magazine Evan Davis, Alan Mayberry, Tasman Anderson, on a monthly basis and hope that you continue to Paul Panayi, Nathan Miller, Barrie Mahoney, enjoy the articles, information, news and special Ben Angel, Ash Hogan, George Alexander, Thomas Kenneth Jones, Chris Gregoriou features presented on a monthly basis. Cover picture Please enjoy your April Issue of Q Magazine. Todd McKenny as Peter Allen Photographic Contributions In other news, ABSOLUT VODKA is proud to introduce Q Photos, Benjamin Ashe (Peel), ‘ABSOLUT NO LABEL’, a bold and innovative project Alan Mayberry (Greyhound), Leigh where the brand is challenging labels and prejudice Klooger (Doug’s Birthday & Pokeys) about sexual identity. This limited edition ABSOLUT [email protected] bottle - with no label and no logo - has launched in Distribution Australia as a visionary manifestation of a world where [email protected] no labels exist.