Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage

Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage Renata Grossi Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Grossi, Renata, author. Title: Looking for love in the legal discourse of marriage / Renata Grossi. ISBN: 9781925021790 (paperback) 9781925021820 (ebook) Subjects: Marriage. Love. Marriage law. Husband and wife. Same-sex marriage. Dewey Number: 306.872 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Nic Welbourn and layout by ANU Press Cover image: Ali and David asleep 12.01am-12.31 from the Journey to Morning Series by Blaide Lallemand and Hilary Cuerden-Clifford. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction . 1 Framing the Questions of the Book . 3 The Importance of Law and Emotion Scholarship . 3 The Meaning of Love . 9 Outline of the Book . 15 1. Love and Marriage . 17 Introduction . 17 The Common Law of Marriage . 17 Nineteenth-Century Reform . 21 Twentieth-Century Reform . 23 The Meanings of Marriage: Holy Estate, Oppressive Patriarchy, Equal Love . 26 Consequences of the Love Marriage (The Feminist Critique of Love) . 31 Conclusion . 37 2. The Diminishing Significance of Sexual Intercourse . 39 Introduction . 39 The Old Discourse of Sex and Marriage . -

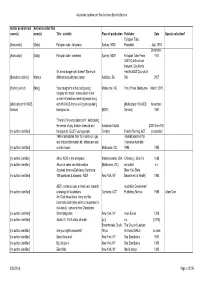

Books at 2016 05 05 for Website.Xlsx

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Book Collection Author or editor last Author or editor first name(s) name(s) Title : sub-title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection? Fallopian Tube [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : fallopiana Sydney, NSW Pamphlet July, 1974 December, [Antolovich] [Gaby] Fallopian tube : madness Sydney, NSW Fallopian Tube Press 1974 GLBTIQ with cancer Network, Gay Men's It's a real bugger isn't it dear? Stories of Health (AIDS Council of [Beresford (editor)] Marcus different sexuality and cancer Adelaide, SA SA) 2007 [Hutton] (editor) [Marg] Your daughter's at the door [poetry] Melbourne, VIC Panic Press, Melbourne March, 1975 Inequity and hope : a discussion of the current information needs of people living [Multicultural HIV/AIDS with HIV/AIDS from non-English speaking [Multicultural HIV/AIDS November, Service] backgrounds [NSW] Service] 1997 "There's 2 in every classroom" : Addressing the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual and Australian Capital [2001 from 100 [no author identified] transgender (GLBT) young people Territory Family Planning, ACT yr calendar] 1995 International Year for Tolerance : gay International Year for and lesbian information kit : milestones and Tolerance Australia [no author identified] current issues Melbourne, VIC 1995 1995 [no author identified] About AIDS in the workplace Massachusetts, USA Channing L Bete Co 1988 [no author identified] Abuse in same sex relationships [Melbourne, VIC] not stated n.d. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome : [New York State [no author identified] 100 questions & answers : AIDS New York, NY Department of Health] 1985 AIDS : a time to care, a time to act, towards Australian Government [no author identified] a strategy for Australians Canberra, ACT Publishing Service 1988 Adam Carr And God bless Uncle Harry and his roommate Jack (who we're not supposed to talk about) : cartoons from Christopher [no author identified] Street Magazine New York, NY Avon Books 1978 [no author identified] Apollo 75 : Pix & story, all male [s.l.] s.n. -

APRIL 2010 Enjoyed Nationally & Internationally!

Made in Melbourne! APRIL 2010 Enjoyed Nationally & Internationally! APRIL 2010 q comment: BIRTHDAY TIME Issue 67 It delights me to announce that Q Magazine’s first issue was way back in April 2004 and that this issue Publisher & Editor Brett Hayhoe marks the beginning of our seventh year. +61 (0) 422 632 690 [email protected] I want to again thank those people (writers, contributors, advertisers, publicists and the like) who Editorial have made the ride a truly enjoyable one. Without [email protected] these incredibly generous people and YOU our loyal Sales and Marketing readers Q Magazine could not do it. [email protected] The support we have had from people throughout Design Melbourne, Australia and the world has been amazing Uncle Brett Designs & Graphics and humbling. Contributing Writers Pete Dillon, Addam Stobbs, Brett Hayhoe, I look forward to continuing to bring you Q Magazine Evan Davis, Alan Mayberry, Tasman Anderson, on a monthly basis and hope that you continue to Paul Panayi, Nathan Miller, Barrie Mahoney, enjoy the articles, information, news and special Ben Angel, Ash Hogan, George Alexander, Thomas Kenneth Jones, Chris Gregoriou features presented on a monthly basis. Cover picture Please enjoy your April Issue of Q Magazine. Todd McKenny as Peter Allen Photographic Contributions In other news, ABSOLUT VODKA is proud to introduce Q Photos, Benjamin Ashe (Peel), ‘ABSOLUT NO LABEL’, a bold and innovative project Alan Mayberry (Greyhound), Leigh where the brand is challenging labels and prejudice Klooger (Doug’s Birthday & Pokeys) about sexual identity. This limited edition ABSOLUT [email protected] bottle - with no label and no logo - has launched in Distribution Australia as a visionary manifestation of a world where [email protected] no labels exist. -

Author Title Place of Publication Publisher Date Special Collection Wet Leather New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 up Cain

Books Author Title Place of publication Publisher Date Special collection Wet leather New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 Up Cain London, United Kingdom Cain of London 197? Up and coming [USA] [s.n.] 197? Welcome to the circus shirkus [Townsville, Qld, Australia] [Student Union, Townsville College of [1978] Advanced Education] A zine about safer spaces, conflict resolution & community [Sydney, NSW, Australia] Cunt Attack and Scumsystemspice 2007 Wimmins TAFE handbook [Melbourne, Vic, Australia] [s.n.] [1993] A woman's historical & feminist tour of Perth [Perth, WA, Australia] [s.n.] nd We are all lesbians : a poetry anthology New York, NY, USA Violet Press 1973 What everyone should know about AIDS South Deerfield, MA, USA Scriptographic Publications Pty Ltd 1992 Victorian State Election 29 November 2014 : HIV/AIDS : What [Melbourne, Vic, Australia] Victorian AIDS Council/Living Positive 2014 your government can do Victoria Feedback : Dixon Hardy, Jerry Davis [USA] [s.n.] c. 1980s Colin Simpson How to increase the size of your penis Sydney, NSW, Australia Venus Publications Pty.Ltd 197? HRC Bulletin, No 72 Canberra, ACT, Australia Humanities Research Centre ANU 1993 It was a riot : Sydney's First Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras Sydney, NSW, Australia 78ers Festival Events Group 1998 Biker brutes New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1983 Colin Simpson HIV tests and treatments Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia AIDS Council of NSW (ACON) 1997 Fast track New York, NY, USA Star Distributors 1980 Colin Simpson Denver University Law Review Denver, CO, -

Keynotes, Abstracts and Biographies

Beyond the Culture Wars LGBTIQ History Now Keynotes Jagose, Annamarie, ‘Our Bodies, Our Archives Given that the term “culture wars” is a distinctively American import, when we come to thinking about how it might resonate in our Australian contexts, it is worth keeping in mind the materiality of place. After some consideration of my own embroilment in cultural contestation regarding my queer research program, I return to this notion of the materiality of place to suggest that the archive offers us capacious opportunities for engagement that move beyond the agonistic stand-offs associated with what Janice Irvine describes as the “recursive, unyielding civic arguments popularly known as culture wars.” Bio: Annamarie Jagose is internationally known as a scholar in feminist studies, lesbian/gay studies and queer theory. She is the author of four monographs, most recently Orgasmology, which takes orgasm as its scholarly object in order to think queerly about questions of politics and pleasure; practice and subjectivity; agency and ethics. She is also an award-winning novelist and short story writer. Wilcox, Melissa, ‘Apocrypha and Sacred Stories: Queer Worldmaking, Historical “Truth,” and the Ethics of Research in Living Communities’ While historical research may always have contemporary consequences, in that the tales one tells of the past are rarely inert or disinterested in the present day, the epistemological and ethical challenges of historical research within living communities are particularly marked. The field of religious studies offers one framework for thinking through such challenges in its long-standing attention to the potency of sacred story, whether specifically religious or not, for the enterprise of worldmaking. -

Printed Guide

-)$35--! #%,%"2!4).' 15%%2#5,452% -)$35--! #%,%"2!4).' 15%%2#5,452% -)$35--! #%,%"2!4).' 15%%2#5,452% 17 Jan —7 Feb 2010 -)$35--! #%,%"2!4).' 15%%2#5,452% -)$35--! #%,%"2!4).' 15%%2#5,452% -)$35--! #%,%"2!4).' 15%%2#5,452% Chair’s Welcome Contents & Key Chair’s WELCOME CONTENTS Midsumma celebrates queer culture. Messages of Support 4 Ticketing Information 5 Queer culture is about inclusion and PREMIER EVENTS acceptance, regardless of difference. MIDSUMMA CARNIVAL 6 TDANCE 7 Midsumma is for anyone who doesn’t PINK SHORTS 9 need a label to describe their sexuality or PRIDE MARCH 11 Nex•Us 13 gender, as well as those who do. That’s why GeNtlemeN Prefer Blokes 13 Midsumma is a festival that keeps getting GAYME 15 more interesting. VEILED IN PLAIN SIGHT 15 VISUAL ARTS This year’s program is a ripper, and we know you’ll find some gems amongst it. Queer City 16 Yarra Arts 22 Darebin Arts 24 Huge thanks and congratulations to the Visual Arts 26 Adam Lowe Group, the rest of the Board, all our volunteers, fantastic sponsors & FESTIVAL HUBS government supporters. The Butterfly Club 28 -)$35--! Gasworks Arts Park 32 The Midsumma#%,%"2!4 )community.' is fantastically the Glasshouse Hotel 34 diverse,1 5so%% 2let’s#5 ,all45 2celebrate% that in 2010. the Northcote town Hall 36 COMMUNITY EVENTS LISA WATTS – CHAIR, Midsumma Festival Inc. Performing Arts 38 Live Music 44 -)$35--! Film 48 #%,%"2!4).' Literature & Spoken Word 50 15%%2#5,452% Social & Community 54 Sports 60 Parties & Nightlife 66 FESTIVAL DETAILS -)$35--! Festival Planner 76 #%,%"2!4).' Maps 80 15%%2#5,452% Venue Listings 82 Credits & Involvement 84 TICKETING FESTIVAL ICONS Head to midsumma.org.au Your Key to the symbols in for all your festival tickets! the Midsumma guide For further information regarding ticketing please turn to page 5. -

![Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 29 November 2012] P9042b-9045A Hon Lynn Maclaren [1] MARRIAGE EQUALITY BILL 2012](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6936/extract-from-hansard-council-thursday-29-november-2012-p9042b-9045a-hon-lynn-maclaren-1-marriage-equality-bill-2012-3526936.webp)

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 29 November 2012] P9042b-9045A Hon Lynn Maclaren [1] MARRIAGE EQUALITY BILL 2012

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 29 November 2012] p9042b-9045a Hon Lynn MacLaren MARRIAGE EQUALITY BILL 2012 Introduction Bill introduced by Hon Lynn MacLaren. Point of Order Hon NICK GOIRAN: Mr President, I seek your ruling on whether the motion moved by the honourable member contravenes section 51 of the Constitution when read with section 109 of the Constitution and sections 5, 6 and 46 of the Marriage Act. In brief, I just draw to your attention that section 51(xxi) of the Constitution confers the issue of legislating in terms of marriage specifically to the federal Parliament. I also draw to your attention, Mr President, that section 109 of the Constitution provides that where there is going to be an inconsistency between a commonwealth law and a state law, it will be found to be invalid. I also draw to your attention, Mr President, that section 6 of the Marriage Act, which is of course a commonwealth act which this motion would seek to contravene—as you would be aware, Mr President, the honourable member seeks to include the registration of same-sex marriages— explicitly preserves the validity of state and territories relating only to the registration of marriage. Mr President, in my view it is important for you to take into account the current definition of marriage, as found in section 5 of that same commonwealth act. Mr President, you would be aware that “marriage” has been defined by the commonwealth in section 5(1) of that commonwealth act, and I draw to your attention that it defines marriage as — … the union of a man and a woman to the exclusion of all others, voluntarily entered into for life. -

T-Shirts Place of Box Id No

T-shirts Place of Box Id No. Title Creator Date publication Publisher Description Subjects TXT001 1 The quilt : Australian AIDS Memorial 1994 Sydney, NSW, AIDS Memorial Quilt Singlet. Words superimposed on rectangular design. Additional HIV/AIDS Quilt Project Australia Project text: "Sydney Display - Darling Harbour - 22nd-23rd January 1994". Cotton, mauve and black lettering on a white background. TXT001 2 1996 AIDS Awareness Week Tour 1996 Sydney, NSW, Outline sketch of two human figures (brown) wrapped together HIV/AIDS Australia by a red ribbon. Additional text: "Proudly sponsored by Fitpack, Needle Syringe Transportation Solutions : Sydney and Metropolitan Areas, Tamworth, Gunnedah, Narrabri, Moree, Bingara, Tenterfield, Inverell, Glen Innes, Armidale, Wollongong, Nowra, Grafton, Maclean, Lismore, Murwillumbah, Tweed Heads, Goulburn, Queanbeyan Cooma, Bega, Narooma, Mouruya, Young, The Entrance, Terrigal, Tuggerah, Woy Woy, Nepean, Penrith, Blue Mountains, Albury, Wagga, Wagga, Orange, Broken Hill, Wilcannia. World AIDS Day, Australia, December 1st 1996". Cotton, brown and red lettering on a fawn background. TXT001 3 [Red ribbon with rainbow patch] Red ribbon with rainbow patch, cotton on a black background. HIV/AIDS TXT001 4 Mars Bar 1993 Adelaide, SA, Mars Bar Hotel Cross of male and female figures, cotton, black lettering on a Venues Australia white background. TXT001 5 2001 Pride March Victoria : Embrace S., Antonia 2001 Melbourne, Vic, Pride March River and banks with two trees. Additional text: "Primus", cotton, Pride diversity Australia black and white lettering on a white background. TXT001 8 ICAAP Volunteer 2001 Melbourne, Vic, International Circles of stylised people around a ribbon, logo on sleeves. Cotton, HIV/AIDS; Australia Congress on AIDS in white lettering on a red background. -

Australian Christian Lobby Submission

Submission 021 0 ael australian christian lobby -~- i Submission to the Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs Concerning the Marriage Amendment Bill 2012 and the Marriage Equality Amendment Bill 2012 April 2012 ACL National Office 4 Campion St Deakin ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6259 0431 Fax: (02) 6259 0462 Email: [email protected] Website: www.acl.org.au ABN 40 075 120 517 Submission 021 1 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Marriage as a public good ....................................................................................................................... 5 Children do best with married, biological parents ............................................................................. 6 Evidence from the social sciences................................................................................................... 6 The importance of fathers .............................................................................................................. 8 The importance of fathers for girls ................................................................................................. 8 Flaws in methodology of studies favouring same-sex parenting ................................................... 9 Marriage as a social good - Conclusion -

Intimacy and Power: Approaching Agency and Marriage Equality in Australia

Intimacy and Power: Approaching Agency and Marriage Equality in Australia Rhys Herden University of Sydney Abstract At its most fundamental, ‘making a mark’ describes a particular mode of human agency. For LGBTIQA* Australians, the struggle for the recognition of this agency has long been a feature of living in Australia, and its political landscape. In recent years, marriage equality has become the focus of this struggle for recognition, but marriage equality also provides an opportunity to examine the internal mechanics of how power operates in Australian society. This paper argues that the concept of intimacy is at the centre of the operation of power in this context, and will examine this under the framework of intimate citizenship. It will examine the history of the LGBT+ rights movement in Australia, alongside the historical development of the marriage equality movement. Moreover, it will demonstrate that the agency of LGBT+ Australians in this political struggle is only further indication that intimacy provides a unique channel through which power is experienced and enacted. Keywords marriage equality; same-sex marriage; intimacy; sexuality; citizenship; intimate citizenship; sexual citizenship; queer theory; Australia The movement toward marriage equality for same-sex couples in Australia has often been viewed as having contradictory achievements. On the one hand, advocates for marriage equality stressed the potential windfall of entitlement, mostly in symbolic terms, for LGBT+ Australians and their families. In a review of the documentary film Growing up Gayby by Maya Newell in the Sydney Morning Herald, readers are encouraged to view families of same-sex couples as “just a normal family” (Kalina 2013). -

Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage

Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage Looking for Love in the Legal Discourse of Marriage Renata Grossi Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Grossi, Renata, author. Title: Looking for love in the legal discourse of marriage / Renata Grossi. ISBN: 9781925021790 (paperback) 9781925021820 (ebook) Subjects: Marriage. Love. Marriage law. Husband and wife. Same-sex marriage. Dewey Number: 306.872 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Nic Welbourn and layout by ANU Press Cover image: Ali and David asleep 12.01am-12.31 from the Journey to Morning Series by Blaide Lallemand and Hilary Cuerden-Clifford. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction . 1 Framing the Questions of the Book . 3 The Importance of Law and Emotion Scholarship . 3 The Meaning of Love . 9 Outline of the Book . 15 1. Love and Marriage . 17 Introduction . 17 The Common Law of Marriage . 17 Nineteenth-Century Reform . 21 Twentieth-Century Reform . 23 The Meanings of Marriage: Holy Estate, Oppressive Patriarchy, Equal Love . 26 Consequences of the Love Marriage (The Feminist Critique of Love) . 31 Conclusion . 37 2. The Diminishing Significance of Sexual Intercourse . 39 Introduction . 39 The Old Discourse of Sex and Marriage . -

Archival Collections

Archival Collections Box Id Title Author Date Description Extent Finding aid ARS006 Nation Review Press Clippings c.1972- Press clippings, mainly from Nation Review pasted into a scrapbook with 40cm (1 scrapbook) No Collection c.1974 newsprint quality pages, approx 32 x 40 cm. Source not known. ARS012 Records of Gay and Lesbian Gay and Lesbian Archives of 2015 Papers compiled by Graham Willett relating to discussions about the 2cm (1 file) No Archives of Western Australia Western Australia (GALAWA) future of GALAWA (GALAWA) ARS007 Papers of Arthur Groves [Groves, Arthur] 1906-1920 The Papers of Arthur Groves contains a single volume of hHandwritten 1cm (1 folder) Excel poems, bound, addressed to Stuart Hunter, Box 19, Lakes Entrance, inscribed 'To my friend from his friend/the author of these verses/London/July 1920, with a photo accompanied by signature 'Arthur R Groves' on the following page. The poems are dated 1906 to 1919 (see caption list). ARC011 Papers of Kevin A A, Kevin, ?- 1950s-2000s Mostly clippings from 70s to 2001. 45cm (1 box) No ARS003 Records of ACT UP Canberra ACT UP Canberra 1990-1991 The Records of ACT UP Canberra include: agenda, minutes, financial 3cm (1 folder) No documents, correspondence, media releases, contact list, demonstration flyers, notes, newspaper clippings, and badge and sticker designs . Also includes documents relating to ACT UP North Coast and ACT UP Sydney. Folder of records donated by the AIDS Council of the ACT in 2015. ARC159 Records of the Adelaide Adelaide Directory Collective 1984-1989 The Records of the Adelaide Directory Collective relate to the governance 8cm (1 box) No Directory Collective of the Collective.