Thesis Polygamy on the Web: an Online Community for An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic News Staff Writer EXETER | for the Average Muggle, the Activities of Friday Evening Must Have Seemed Strange

INSIDE: TV ListinGS 26,000 COPIES Please Deliver Before FRIDAY, JULY 27, 2007 Vol. 33 | No. 31 | 2 Sections |32 Pages Cyan Magenta Area witches and wizards gather for book release Yellow BY SCOTT E. KINNEY ATLANTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER EXETER | For the average Muggle, the activities of Friday evening must have seemed strange. Black Witches and wizards of all ages gathered in down- town Exeter on Friday night anxiously awaiting the arrival of the seventh and final installment of the J.K. Rowling series, “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal- lows.” Hundreds of wand-wielding magicians flooded Water Street awaiting the stroke of midnight when they would be among the first to purchase the book. Two hours prior to Water Street Bookstore opening its doors, those in attendance were treated to a variety of entertainment including “Out-Fox Mrs. Weasley,” “Divine Divinations with Professor Trelawney,” “Olli- vanders Wand Shop,” “Advanced Potion Making,” “Quidditch World Cup,” and “The Great Hogwarts Hunt.” POTTER Continued on 14A• Obama courts votes in Hampton 2002 SATURN BY LIZ PREMO as well as David O’Connor, SC2 COUPE ATLANTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER principal of Marston School Auto, Leather, Sunroof, HAMPTON | A spirited where the candidate held a 63K Mi, Mint! basketball game at Hampton town hall meeting an hour #X1511P Academy was the precursor or so later. for last Friday’s energized According to campaign ONLY campaign stop in Hampton staffers, approximately 600 $ SERVICE by Democratic presidential people were in attendance 7,995 AND SALES candidate -

By Hélène Thibault

C A P P A P E R N O . 2 5 5 By Hélène Thibault Photo: IMDb As a soft authoritarian state whose society is considered relatively socially conservative, Kazakhstan’s regulation of sexual practices and marriage blends liberal lifestyles with patriarchal outlooks. The issue of polygyny has been well Hélène Thibault has been Assistant researched in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, often in light of Professor of Political Science and women’s economic vulnerability, the re-traditionalization of International Relations at Nazarbayev gender roles, and increasing religiosity. In contrast, this paper University, Kazakhstan, since 2016. She specializes in ethnography, gender, and the highlights the cosmopolitan, sometimes glamourous, character securitization of Islam in Central Asia. She is of polygyny in oil-rich Kazakhstan. In Kazakhstan, many the author of Transforming Tajikistan: Nation- Building and Islam in Central Asia associate polygyny with women’s economic vulnerability and (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017) and has been opportunism, others with the country’s perceived demographic published in Central Asian Survey, Ethnic problems, and still others with religious traditions and and Racial Studies, and the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, among others. patriarchal oppression. However, interviews and focus groups I Her current projects look at gender issues in conducted in 2019-2020 reveal that becoming a second wife Central Asia, including marriage, polygyny, and male sex-work. (locally referred to as tokal) represents a way for some women to retain independence in their relationships. CAP Paper No. 255 s a soft authoritarian state whose society is considered relatively socially conservative, Kazakhstan’s regulation of sexual practices and marriage blends liberal lifestyles with A patriarchal outlooks. -

Polygyny: a Study of Religious Fundamentalism Margaret L

Polygyny: A Study of Religious Fundamentalism Margaret L. Granath Submitted under the supervision of Professor Kathleen Collins to the University Honors Program at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts, magna cum laude, in political science. April 24, 2021 2 Acknowledgements: I would like to give thanks: To Prof. Kathleen Collins, for her guidance throughout the writing process of this work. She took a chance on me when I was a freshman, allowing me to work with her as a research assistant for three years of college until I wrote this thesis under her supervision. I am a better writer, a better researcher, and a better thinker due to her mentorship. To my parents, Al and Teresa. They never restricted what I read as a child (which turned out to be a good thing, because I read Under the Banner of Heaven in 7th grade, which turned into the inspiration for this thesis). Thank you for fostering my curiosity, then and now. To my siblings, Ellica and Kyle, thank you for allowing me to bore you with conversations about religion at dinner. All of my love. To Scott Romano, for delivering various fast foods to me during the writing process—I owe you many. Thank you for always reminding me of my worth (and to take a break). To Morgan McElroy, for his friendship. Editing your papers was a much-needed reprieve. Thank you for being there. To the women of Gamma Phi Beta, for listening each week as I shared the struggles and successes of this writing process. -

William Smith, Isaach Sheen, and the Melchisedek & Aaronic Herald

William Smith, Isaach Sheen, and the Melchisedek & Aaronic Herald by Connell O'Donovan William Smith (1811-1893), the youngest brother of Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith, was formally excommunicated in absentia from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on October 19, 1845.1 The charges brought against him as one of the twelve apostles and Patriarch to the church, which led to his excommunication and loss of position in the church founded by his brother, included his claiming the “right to have one-twelfth part of the tithing set off to him, to be appropriated to his own individual use,” for “publishing false and slanderous statements concerning the Church” (and in particular, Brigham Young, along with the rest of the Twelve), “and for a general looseness and recklessness of character which is ill comported with the dignity of his high calling.”2 Over the next 15 years, William founded some seven schismatic LDS churches, as well as joined the Strangite LDS Church and even was surreptitiously rebaptized into the Utah LDS church in 1860.3 What led William to believe he had the right, as an apostle and Patriarch to the Church, to succeed his brother Joseph, claiming authority to preside over the Quorum of the Twelve, and indeed the whole church? The answer proves to be incredibly, voluminously complex. In the research for my forthcoming book, tentatively titled Strange Fire: William Smith, Spiritual Wifery, and the Mormon “Clerical Delinquency” Crises of the 1840s, I theorize that William may have begun setting up his own church in the eastern states (far from his brother’s oversight) as early as 1842. -

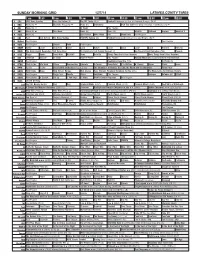

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Negotiating Polygamy in Indonesia

Negotiating Polygamy in Indonesia. Between Muslim Discourse and Women’s Lived Experiences Nina Nurmila Dra (Bandung, Indonesia), Grad.Dip.Arts (Murdoch University, Western Australia), MA (Murdoch University) Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2007 Gender Studies - Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT Unlike most of the literature on polygamy, which mainly uses theological and normative approaches, this thesis is a work of social research which explores both Indonesian Muslim discourses on polygamy and women’s lived experiences in polygamous marriages in the post-Soeharto period (after 1998). The thesis discusses the interpretations of the Qur’anic verses which became the root of Muslim controversies over polygamy. Indonesian Muslim interpretations of polygamy can be divided into three groups based on Saeed’s categorisation of the Muslim approaches to the Qur’an (2006b: 3). First, the group he refers to as the ‘Textualists’ believe that polygamy is permitted in Islam, and regard it as a male right. Second, the group he refers to as ‘Semi-textualists’ believe that Islam discourages polygamy and prefers monogamy; therefore, polygamy can only be permitted under certain circumstances such as when a wife is barren, sick and unable to fulfil her duties, including ‘serving’ her husband’s needs. Third, the group he calls ‘Contextualists’ believe that Islam implicitly prohibits polygamy because just treatment of more than one woman, the main requirement for polygamy, is impossible to achieve. This thesis argues that since the early twentieth century it was widely admitted that polygamy had caused social problems involving neglect of wives and their children. -

1 Comic Book Characters and Historical Fiction: Where Alex Beam

Comic Book Characters and Historical Fiction: Where Alex Beam Gets Joseph Smith’s Polygamy Wrong By Brian C. Hales Alex Beam addresses Joseph Smith’s polygamy in chapter 5 of American Crucifixion. From a scholarly standpoint, the chapter suffers from multiple weaknesses including the predominant use of secondary sources, quoting of problematic evidences apparently without checking their reliability, ignoring of historical data that contradicts his position, promotion of narrow and often extreme interpretations of available documents, and going beyond the evidence in constructing conclusions. I’ve been told that later chapters in American Crucifixion are generally historically accurate. Unfortunately, Beam’s treatment of the Prophet and the practice of plural marriage is so egregious and problematic, that after reading the chapter, observers will unalterably identify Joseph Smith as an adulterer, hypocrite, and fraud. When Joseph is later killed in a firestorm at Carthage, the reader may lament the injustice, but they really do not care because Beam has firmly established that Joseph was a scoundrel who probably deserved to die anyway. To me Beam’s version of Nauvoo plurality reads like historical fiction describing comic book characters who do illogical things. Beam has classified his book as “popular non-fiction,” and affirms that non-fiction works should be accurate and truthful. Accordingly, Beam’s book and his claims about its accuracy create a paradox. One of the greater weaknesses in Chapter 5 is Beam’s tendency to repeat secondary sources. There he quotes Linda King Newell and Valeen Avery eight times; Richard Van Wagoner three times; and Richard Bushman, George D. -

(Arranged) Marriage: an Autoethnographical Exploration of a Modern Practice

TCNJ JOURNAL OF STUDENT SCHOLARSHIP VOLUME XXII APRIL 2020 FIRST COMES (ARRANGED) MARRIAGE: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHICAL EXPLORATION OF A MODERN PRACTICE Author: Dian Babu Faculty Sponsor: John Landreau Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies ABSTRACT This article uses autoethnography and family interviews to analyze the modern cultural practice of arranged marriage from my standpoint as a first generation Indian-American. Borrowing from Donna Haraway’s notion of situated knowledge, Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism, and W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of double consciousness, this article presents the idea of immigrant consciousness and precedes to contend with the sociocultural circumstances, such as transnational migration, assimilation, and racism-classism, that have prompted the evolution of a modern iteration of arranged marriage. The central question that informs this paper is what does arranged marriage mean – and how can it be defended and/or criticized – in different circumstances and from different standpoints in the transnational South Asian context? INTRODUCTION Dating is foreign to me. Is that strange to hear? Let me qualify that statement: American dating is foreign to me. I am a first-generation Indian-American, Christian girl. I am the child of parents who immigrated from India to the United States and who were brought together through an arranged marriage. The practice of arranged marriage runs through most of my family history and dating is a relatively new practice to us collectively. Important to note, however, is that my family members’ individual histories, like all histories, do not run on one generalized path. I have family members who never married, who remarried, who had forced marriages, who had “love marriages,” who married young, who married non- Indian people, who divorced, and so on and so forth. -

Wednesday Morning, Jan. 27

WEDNESDAY MORNING, JAN. 27 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) 47008 AM Northwest Be a Millionaire The View Journalist E.D. Hill. (N) Live With Regis and Kelly (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) 626517 (cc) 17282 21973 (cc) (TV14) 59843 (TVG) 46379 KOIN Local 6 News 33331 The Early Show (N) (cc) 69244 Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right Contestants bid The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 Early at 6 80824 66244 for prizes. (N) (TVG) 88379 (TV14) 91843 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Gayle Haggard; Sharon Osbourne. (N) (cc) 867060 Rachael Ray (cc) (TVG) 86911 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) 44534 Lilias! (cc) (TVG) Between the Lions Curious George Sid the Science Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Tribute to Number Clifford the Big Dragon Tales WordWorld (TVY) Martha Speaks 10/KOPB 10 10 19350 (TVY) 89517 (TVY) 25824 Kid (TVY) 43701 (TVY) 27718 (TVY) 26089 Seven. (N) (cc) (TVY) 35398 Red Dog 91379 (TVY) 39553 11060 (TVY) 29089 Good Day Oregon-6 (N) 71602 Good Day Oregon (N) 16176 The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 20466 Paid 86447 Paid 24621 The Martha Stewart Show (N) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (TVG) 15447 Paid 86486 Paid 17008 Paid 49195 Paid 28602 Through the Bible Life Today 15553 Christians & Jews Paid 34176 Paid 91060 Paid 67319 Paid 78244 Paid 79973 22/KPXG 5 5 16282 67355 Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- The Word in the Inspirations Lifestyle Maga- Behind the Alternative James Robison Marilyn -

WOMEN's STUDIES a Reader

WOMEN'S STUDIES A Reader Edited by Stevi Jackson, Karen Atkinson, Deirdre Beddoe, Teh Brewer, Sue Faulkner, Anthea Hucklesby, Rose Pearson, Helen Power, Jane Prince, Michele Ryan and Pauline Young New York London Toronto Sydney Tokyo Singapore CONTENTS Introduction: About the Reader xv Feminist Social Theory I Edited and Introduced by Stevi Jackson Introduction 3 1 Shulamith Firestone The Dialectic of Sex 7 2 Juliet Mitchell Psychoanalysis and Feminism 9 3 Michele Barrett Women's Oppression Today 11 4 Heidi Hartmann The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism 13 5 Christine Delphy Sex Classes 16 6 Sylvia Walby Forms and Degrees of Patriarchy 18 7 Parveen Adams, Rosaline Coward and Elizabeth Cowie Editorial, m// 1 19 8 Jane Flax Postmodernism and Gender Relations in Feminist Theory 20 9 Luce Irigaray Women: equal or different 21 10 Monique Wittig One is not born a woman 22 I I Hazel Carby White Women Listen! 25 12 Denise Riley Am I That Name? 26 13 Tania Modleski Feminism Without Women 27 14 Liz Stanley Recovering 'Women' in History from Historical Deconstructionism 28 1.15 Avtar Brah Questions of Difference and International Feminism 29 Further Reading 34 Contents Women's Minds: psychological and psychoanalytic theory 37 Edited and Introduced by Jane Prince Introduction 39 2.1 Jean Grimshaw Autonomy and Identity in Feminist Thinking 42 2.2 Wendy Hollway Male Mind and Female Nature 45 2.3 Corinne Squire Significant Differences: feminism in psychology 50 2.4 Valerie Walkerdine Femininity as Performance 53 2.5 Nancy Chodorow Family Structure -

Pastorale Nureyev Park Appeal Dixie Union Dixieland Band

Consigned by Woodfort Stud 401 401 Gone West Zafonic Iffraaj (GB) Zaizafon BAY FILLY (IRE) Nureyev April 8th, 2011 Pastorale Park Appeal (Third Produce) Dixieland Band Dixie Union Hams (USA) She's Tops (2003) Desert Wine Desert Victress Elegant Victress E.B.F. Nominated. B.C. Nominated. 1st dam HAMS (USA): placed twice at 3; dam of 2 previous foals; 2 runners; 2 winners: Super Market (IRE) (08 f. by Refuse To Bend (IRE)): 4 wins at 2 in Italy. Dixie's Dream (IRE) (09 c. by Hawk Wing (USA)): 2 wins at 2 and 3, 2012 and placed 5 times. 2nd dam DESERT VICTRESS (USA): placed twice at 2 and 3; also winner at 3 in U.S.A. and placed 3 times; dam of 10 foals; 9 runners; 3 winners inc.: DESERT DIGGER (USA) (f. by Mining (USA)): winner at 2 in U.S.A. and £99,649 viz. Sorrento S., Gr.2, placed 5 times inc. 2nd Del Mar Debutante S., Gr.2 and 3rd Princess S., Gr.2; dam of winners inc.: SIRMIONE (USA): won HBPA H. and 2nd Ellis Park Turf S., L. Back Packer (USA): winner in U.S.A., 2nd Transylvania S., L. 3rd dam ELEGANT VICTRESS (CAN) (by Sir Ivor (USA)): 3 wins at 3 in U.S.A. and placed 5 times; dam of 12 foals; 10 runners; 7 winners inc.: EXPLICIT (USA): 6 wins in U.S.A. and £404,504 inc. True North Breeders' Cup H., Gr.2, Count Fleet Sprint H., Gr.3, Pelleteri Breeders' Cup H., L. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books.