Marrying Polygamy Into Title Vii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlantic News Staff Writer EXETER | for the Average Muggle, the Activities of Friday Evening Must Have Seemed Strange

INSIDE: TV ListinGS 26,000 COPIES Please Deliver Before FRIDAY, JULY 27, 2007 Vol. 33 | No. 31 | 2 Sections |32 Pages Cyan Magenta Area witches and wizards gather for book release Yellow BY SCOTT E. KINNEY ATLANTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER EXETER | For the average Muggle, the activities of Friday evening must have seemed strange. Black Witches and wizards of all ages gathered in down- town Exeter on Friday night anxiously awaiting the arrival of the seventh and final installment of the J.K. Rowling series, “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal- lows.” Hundreds of wand-wielding magicians flooded Water Street awaiting the stroke of midnight when they would be among the first to purchase the book. Two hours prior to Water Street Bookstore opening its doors, those in attendance were treated to a variety of entertainment including “Out-Fox Mrs. Weasley,” “Divine Divinations with Professor Trelawney,” “Olli- vanders Wand Shop,” “Advanced Potion Making,” “Quidditch World Cup,” and “The Great Hogwarts Hunt.” POTTER Continued on 14A• Obama courts votes in Hampton 2002 SATURN BY LIZ PREMO as well as David O’Connor, SC2 COUPE ATLANTIC NEWS STAFF WRITER principal of Marston School Auto, Leather, Sunroof, HAMPTON | A spirited where the candidate held a 63K Mi, Mint! basketball game at Hampton town hall meeting an hour #X1511P Academy was the precursor or so later. for last Friday’s energized According to campaign ONLY campaign stop in Hampton staffers, approximately 600 $ SERVICE by Democratic presidential people were in attendance 7,995 AND SALES candidate -

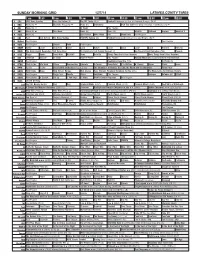

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Thesis Polygamy on the Web: an Online Community for An

THESIS POLYGAMY ON THE WEB: AN ONLINE COMMUNITY FOR AN UNCONVENTIONAL PRACTICE Submitted by Kristen Sweet-McFarling Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2014 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Lynn Kwiatkowski Cindy Griffin Barbara Hawthorne Copyright by Kristen Sweet-McFarling 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT POLYGAMY ON THE WEB: AN ONLINE COMMUNITY FOR AN UNCONVENTIONAL PRACTICE This thesis is a virtual ethnographic study of a polygamy website consisting of one chat room, several discussion boards, and polygamy related information and links. The findings of this research are based on the interactions and activities of women and men on the polygamy website. The research addressed the following questions: 1) what are individuals using the website for? 2) What are website members communicating about? 3) How are individuals using the website to search for polygamous relationships? 4) Are website members forming connections and meeting people offline through the use of the website? 5) Do members of the website perceive the Internet to be affecting the contemporary practice of polygamy in the U.S.? This research focused more on the desire to create a polygamous relationship rather than established polygamous marriages and kinship networks. This study found that since the naturalization of monogamous heterosexual marriage and the nuclear family has occurred in the U.S., due to a number of historical, social, cultural, political, and economic factors, the Internet can provide a means to denaturalize these concepts and provide a space for the expression and support of counter discourses of marriage, like polygamy. -

Center for Oral History

C O L U M B I A UNIVERSITY Center for Oral History 2013 ANNUA L REPOR T b Contents 1 Letter from the Director 2 Research 4 Biographical Interview 5 Education and Outreach 8 Rule of Law Oral History Project Public Website 9 Telling Lives: Community-Based Oral History 10 Oral History Public Workshop Series, 2012–2013 12 Contact Us [email protected] About the cover images: Alessandro Portelli, 2013 Summer Institute Scroll painting about the events of 9/11/2001 by Patachitra artists in Medinapur, West Bengal, India Summer Institute 2013, fellows’ presentation Sam Robson, Oral History Master of Arts student videographer COLUMBIACOLUMBIA CENTERCENTER FORFOR OORARALL HISTORYHISTORY : 2013 AANNUNNUALAL RREPOEPORTRT 1 Letter from the Director Oral History in Our Times The past year has been remarkably busy and productive, with Our 2013 Summer Institute, Telling the World: Indigenous two large oral history projects coming to a fruitful end and new Memories, Rights, and Narratives, brought together students, initiatives and new directions being undertaken. scholars, and activists from native and indigenous communities around the world. We were especially pleased to have as faculty We have completed a third substantial oral history of Carnegie two old friends: the first graduate of our oral history M.A. program, Corporation, documenting the tenure of Vartan Gregorian, who China Ching, now program officer at the Christensen Fund in San was inaugurated as president in 1997 following his long and Francisco, and our former summer institute fellow and former successful tenure as president at Brown University. Our project faculty member Winona Wheeler, professional oral historian and coincided with Carnegie’s celebration of its centennial, and professor at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada. -

Using Established Medical Criteria to Define Disability: a Proposal to Amend the Americans with Disabilities Act

Washington University Law Review Volume 80 Issue 1 January 2002 Using Established Medical Criteria to Define Disability: A Proposal to Amend the Americans with Disabilities Act Mark A. Rothstein University of Louisville Serge A. Martinez University of Louisville W. Paul McKinney University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Disability Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, and the Medical Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Mark A. Rothstein, Serge A. Martinez, and W. Paul McKinney, Using Established Medical Criteria to Define Disability: A Proposal to Amend the Americans with Disabilities Act, 80 WASH. U. L. Q. 243 (2002). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol80/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING ESTABLISHED MEDICAL CRITERIA TO DEFINE DISABILITY: A PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT MARK A. ROTHSTEIN* SERGE A. MARTINEZ** W. PAUL MCKINNEY*** I. INTRODUCTION The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA)1 prohibits discrimination in employment,2 public services,3 and public accommodations4 against individuals with disabilities.5 The threshold question, however, of who is an individual with a disability has proven to be more complicated, contentious, and confusing than any of the ADA’s drafters ever could have imagined. The law does not prohibit all discrimination based on disability, and it does not prohibit discrimination against all individuals with disabilities. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2008 No. 148 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. WELCOMING REV. DANNY DAVIS REPUBLICANS TO BLAME FOR Rev. Danny Davis, Mount Hermon ENERGY CRISIS The SPEAKER. Without objection, Baptist Church, Danville, Virginia, of- (Ms. RICHARDSON asked and was fered the following prayer: the gentlewoman from Virginia (Mrs. DRAKE) is recognized for 1 minute. given permission to address the House Loving God, You have shown us what for 1 minute and to revise and extend There was no objection. is good, and that is ‘‘to act justly, to her remarks.) love mercy, and to walk humbly with Mrs. DRAKE. Thank you, Madam Ms. RICHARDSON. Madam Speaker, our God.’’ Speaker. 3 years ago, Republicans passed an en- Help us, Your servants, to do exactly I am proud to recognize and welcome ergy plan that they said would lower that, to be instruments of both justice Dr. Danny Davis, the senior pastor at prices at the pump, drive economic and mercy, exercising those virtues in Mount Hermon Baptist Church in growth and job creation and promote humility. Your word requires it. Our Danville, Virginia. He is accompanied energy independence. I ask you, Amer- Nation needs it. today by his wife of 30 years, Sandy. ica, did it work? The answer is no. Forgive us when we have failed to do Dr. Davis was born in Tennessee and Now we look 3 years later and the that. -

Sister Wives: a New Beginning for United States Polygamist Families on the Eve of Polygamy Prosecution

Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 7 2012 Sister Wives: A New Beginning for United States Polygamist Families on the Eve of Polygamy Prosecution Katilin R. McGinnis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Katilin R. McGinnis, Sister Wives: A New Beginning for United States Polygamist Families on the Eve of Polygamy Prosecution, 19 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 249 (2012). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol19/iss1/7 This Casenote is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. McGinnis: Sister Wives: A New Beginning for United States Polygamist Famili SISTER WIVES: A NEW BEGINNING FOR UNITED STATES POLYGAMIST FAMILIES ON THE EVE OF POLYGAMY PROSECUTION? I. INTRODUCTION "Love should be multiplied, not divided," a statement uttered by one of today's most infamous, and candid, polygamists, Kody Brown, during the opening credits of each episode of The Learning Channel's ("TLC") hit reality television show, Sister Wives.' Kody Brown, a fundamentalist Mormon who lives in Nevada, openly prac- tices polygamy or "plural marriage" and is married in the religious sense to four women: Meri, Janelle, Christine, and Robyn. 2 The TLC website describes the show's purpose as an attempt by the Brown family to show the rest of the country (or at least those view- ers tuning into their show) how they function as a "normal" family despite the fact that their lifestyle is shunned by the rest of society.3 It is fair to say, however, that the rest of the country not only shuns their lifestyle but also criminalizes it with laws upheld against consti- tutional challenge by the Supreme Court in Reynolds v. -

January 26, 2021 Cathy Russell Director, Office of Presidential

January 26, 2021 Cathy Russell Director, Office of Presidential Personnel Gautam Raghavan Deputy Director, Office of Presidential Personnel Dear Ms. Russell and Mr. Raghavan: The co-chairs of the Consortium for Citizens with Disabilities (CCD) Rights Task Force urge the Biden Administration to appoint the following four individuals to the seats for public members of the AbilityOne Commission: Chai Feldblum, Karla Gilbride, Bryan Bashin, and Christina Brandt. CCD is the largest coalition of national organizations working together to advocate for federal public policy that ensures the self-determination, independence, empowerment, integration and inclusion of children and adults with disabilities in all aspects of society. The AbilityOne Program, created by the Javitz Wagner O’Day Act, authorizes the federal government to purchase products and services from organizations that employ individuals with significant disabilities. As the program serves more than 46,000 people with disabilities and accounts for $4 billion in federal contracts, how it operates is of great importance to the disability community. In particular, the composition of the committee that operates the program—the Committee for Purchase from People Who Are Blind or Severely Disabled, known as the AbilityOne Commission—is of concern because that committee will have to grapple with the issues about the program’s structure raised by the 2016 report of the Advisory Committee on Increasing Competitive Integrated Employment for People with Disabilities. We recommend four individuals -

DFPS Eldorado Investigation (December 22, 2008)

Eldorado Investigation A Report from The Texas Department of Family and Protective Services December 22, 2008 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary......................................................................................................................3 The Eldorado Investigation ...........................................................................................................6 Initial Removal...........................................................................................................................6 Court Actions.............................................................................................................................7 A Team Effort............................................................................................................................9 Investigative Activities .............................................................................................................11 Services for Families...............................................................................................................11 Management of the Legal Cases ............................................................................................13 Investigation Results ...............................................................................................................14 Related Events Outside the Scope of the CPS Investigation ..................................................15 Final Summary........................................................................................................................16 -

L¿Amour for Four: Polygyny, Polyamory, and the State¿S Compelling Economic Interest in Normative Monogamy

Emory Law Journal Volume 64 Issue 6 Paper Symposium — Polygamous Unions? Charting the Contours of Marriage Law's Frontier 2015 L¿Amour for Four: Polygyny, Polyamory, and the State¿s Compelling Economic Interest in Normative Monogamy Jonathan A. Porter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation Jonathan A. Porter, L¿Amour for Four: Polygyny, Polyamory, and the State¿s Compelling Economic Interest in Normative Monogamy, 64 Emory L. J. 2093 (2015). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol64/iss6/11 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PORTER GALLEYSPROOFS 5/19/2015 2:36 PM L’AMOUR FOR FOUR: POLYGYNY, POLYAMORY, AND THE STATE’S COMPELLING ECONOMIC INTEREST IN NORMATIVE MONOGAMY ABSTRACT Some Americans are changing the way they pair up, but others aren’t satisfied with pairs. In the last few years, while voters, legislatures, and judiciaries have expanded marriage in favor of same-sex couples, some are hoping for expansion in a different dimension. These Americans, instead of concerning themselves with gender restrictions, want to remove numerical restrictions on marriage currently imposed by states. These people call themselves polyamorists, and they are seeking rights for their multiple-partner relationships. Of course, polygamy is nothing new for the human species. Some scientists believe that polygamy is actually the most natural human relationship, and history is littered with a variety of approaches to polygamous relations. -

Law Clinics and Lobbying Restrictions

University of the District of Columbia School of Law Digital Commons @ UDC Law Journal Articles Publications 2013 Law Clinics and Lobbying Restrictions Marcy L. Karin Kevin Barry Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.udc.edu/fac_journal_articles Part of the Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons LAW CLINICS AND LOBBYING RESTRICTIONS KEVIN BARRY & MARCY KARIN* “Can law school clinics lobby?” This question has plagued professors for decades but has gone unanswered, until now. This Article situates law school clinics within the labyrinthine law of lobbying restrictions and concludes that clinics may indeed lobby. For ethical, pedagogical, and, ultimately, practical reasons, it is critical that professors who teach in clinics understand these restrictions. This Article offers advice to professors and students on safely navigating this complicated terrain. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 987 I. THREE QUESTIONS PROFESSORS SHOULD ASK ABOUT LOBBYING .......................................................................... 991 II. THE CODE’S RESTRICTIONS ON CHARITABLE LOBBYING ... 994 A. Brief History of the Federal Lobbying Restriction on Charities and the Substantial Part and Expenditure Tests ........................................................................... 996 1. Section 501(c)(3)’s Charitable Lobbying Restriction .......................................................... 996 2. The IRS’s “Substantial Part” and “Expenditure” Tests -

The Impact of the Obama Presidency on Civil Rights Enforcement in the United States

Indiana Law Journal Volume 87 Issue 1 Article 20 Winter 2012 The Impact of the Obama Presidency on Civil Rights Enforcement in the United States Joel Friedman Tulane University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Friedman, Joel (2012) "The Impact of the Obama Presidency on Civil Rights Enforcement in the United States," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 87 : Iss. 1 , Article 20. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol87/iss1/20 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Impact of the Obama Presidency on Civil Rights Enforcement in the United States ∗ JOEL WM. FRIEDMAN On Friday, August 4, 1961, police officers in Shreveport, Louisiana, arrested four African American freedom riders after the two men and two women refused to accede to the officers’ orders to exit the whites-only waiting room at the Continental Trailways bus terminal.1 Four thousand miles away, in the delivery room at Kapi’olani Maternity & Gynecological Hospital in Honolulu, Hawaii, Stanley Ann Dunham, a Kansas-born American anthropologist whose family had moved to the island state twenty years earlier, gave birth to the only child that she would have with her first husband, Barack Obama Sr., an ethnic Luo who had come to Hawaii from the Nyanza Province in southwest Kenya to pursue his education at the University of Hawaii.2 Just over forty-seven years later, on November 4, 2008, their son, Barak Obama II, a mixed-race man who identifies as black, was elected the 44th president of the United States.3 The election of the nation’s first African American president was hailed as an event of historic importance.