Imagereal Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submissions of the Plaintiffs

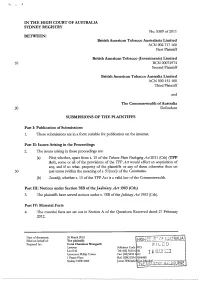

,, . IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA SYDNEY REGISTRY No. S389 of 2011 BETWEEN: British American Tobacco Australasia Limited ACN 002 717 160 First Plaintiff British American Tobacco (Investments) Limited 10 BCN 00074974 Second Plaintiff British American Tobacco Australia Limited ACN 000 151 100 Third Plaintiff and The Commonwealth of Australia 20 Defendant SUBMISSIONS OF THE PLAINTIFFS Part 1: Publication of Submissions 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the internet. Part II: Issues Arising in the Proceedings 2. The issues arising in these proceedings are: (a) First, whether, apart from s. 15 of the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth) (TPP Act), some or all of the provisions of the TPP Act would effect an acquisition of any, and if so what, property of the plaintiffs or any of them otherwise than on 30 just terms (within the meaning of s. 51 (xxxi) of the Constitution. (b) S econdfy, whether s. 15 of the TPP Act is a valid law of the Commonwealth. Part III: Notices under Section 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) 3. The plaintiffs have served notices under s. 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). Part IV: Material Facts 4. The material facts are set out in Section A of the Questions Reserved dated 27 February 2012. Date of document: 26 March 2012 Filed on behalf of: The plaintiffs Prepared by: Corrs Chambers Westgarth riLED Lawyers Solicitors Code 973 Level32 Tel: (02) 9210 6 00 ~ 1 "' c\ '"l , .., "2 Z 0 l';n.J\\ r_,.., I Governor Phillip Tower Fax: (02) 9210 6 11 1 Farrer Place Ref: BJW/JXM 056488 Sydney NSW 2000 JamesWhitmke -t'~r~~-~·r:Jv •,-\:' ;<()IIRNE ' 2 Part V: Plaintiffs' Argument A. -

Exploring the Purposes of Section 75(V) of the Constitution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Australian National University 70 UNSW Law Journal Volume 34(1) EXPLORING THE PURPOSES OF SECTION 75(V) OF THE CONSTITUTION JAMES STELLIOS* I INTRODUCTION There is a familiar story told about section 75(v) of the Constitution. The story starts with the famous United States case of Marbury v Madison,1 where the Supreme Court held that it did not have jurisdiction to grant an order of mandamus directed to the Secretary of State, James Madison, to enforce the delivery of a judicial commission to William Marbury. The story continues that when Andrew Inglis Clark, who was a delegate to the 1891 Constitutional Convention, sat down to draft a constitution to be distributed to the other delegates before the Convention started, he included a provision that was to be the forerunner of section 75(v). The insertion of that provision, it is said, was intended to rectify what he saw to be a flaw in the United States Constitution exposed by the decision in Marbury v Madison. There was little discussion about the clause during the 1891 Convention, and it formed part of the 1891 draft constitution. The provision also found a place in the drafts adopted during the Adelaide and Sydney sessions of the 1897-8 Convention. However, by the time of the Melbourne session of that Convention in 1898, with Inglis Clark not a delegate, no one could remember what the provision was there for and it was struck out. -

Palmer-WA Pltf.Pdf

H I G H C O U R T O F A U S T R A L I A NOTICE OF FILING This document was filed electronically in the High Court of Australia on 23 Apr 2021 and has been accepted for filing under the High Court Rules 2004. Details of filing and important additional information are provided below. Details of Filing File Number: B52/2020 File Title: Palmer v. The State of Western Australia Registry: Brisbane Document filed: Form 27A - Appellant's submissions-Plaintiff's submissions - Revised annexure Filing party: Plaintiff Date filed: 23 Apr 2021 Important Information This Notice has been inserted as the cover page of the document which has been accepted for filing electronically. It is now taken to be part of that document for the purposes of the proceeding in the Court and contains important information for all parties to that proceeding. It must be included in the document served on each of those parties and whenever the document is reproduced for use by the Court. Plaintiff B52/2020 Page 1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA No B52 of 2020 BRISBANE REGISTRY BETWEEN: CLIVE FREDERICK PALMER Plaintiff and STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 10 Defendant PLAINTIFF’S OUTLINE OF SUBMISSIONS Clive Frederick Palmer Date of this document: 23 April 2021 Level 17, 240 Queen Street T: 07 3832 2044 Brisbane Qld 4000 E: [email protected] Plaintiff Page 2 B52/2020 -1- PART I: FORM OF SUBMISSIONS 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the Internet. PART II: ISSUES PRESENTED 2. -

Submission to the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional

Submission to the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples By Dr A. J Wood Senior Research Fellow and Higher Degree Research Manager National Centre for Indigenous Studies Australian National University 1 Is Australia Ready to Constitutionally Recognise Indigenous Peoples as Equals? Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Peoples A Wood1 20 July 2014 I Introduction As the founding document of the nation, the Australian Constitution should at a minimum recognise Indigenous people as the first people of the continent. There also appears to be a consensus that the nation should ‘go beyond’ mere symbolic recognition. The real question is how we achieve this. To stimulate the process, the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (‘the Panel’) produced an excellent, informative and comprehensive report (‘the Panel Report’).2 The Panel Report includes several recommendations which are discussed and critiqued below. This submission, which is the written version of a paper presented at the World Indigenous Legal Conference,3 argues further that in addition to symbolic recognition that there are two main issues that should be addressed in the Constitution: first, that the entrenched constitutional powers of the Parliament to discriminate on the basis of ‘race’ should be rescinded and secondly, that inter alia, racial inequality should be redressed by the recognition of formal equality for all Australian citizens and examines and discusses the related issues. 1 The author is a Senior Research Fellow at the National Centre of Indigenous Studies and teaches at the ANU College of Law. He is a member of the ARC funded National Indigenous Research and Knowledges Network (NIRAKN). -

Court of Australia Bill 2012 and the Military Court of Australia (Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Bill 2012

Submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs Inquiry into the Military Court of Australia Bill 2012 and the Military Court of Australia (Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Bill 2012 The purpose of this submission is to examine four key objections which have been raised to the establishment of a permanent military court in Australia in the form of the Military Court of Australia. The submission is not intended to be comprehensive, but rather seeks to consider some of the legal issues which arise in relation to these four objections.1 The authors do not consider that the first three objections are legitimate bases to reject the establishment of the Military Court of Australia, but are concerned that the fourth objection (the lack of jury trial) may give rise to a future constitutional challenge. The four objections to the establishment of a permanent military court which have been raised are as follows: 1. The establishment of a permanent court is unnecessary given that the current system is not defective This objection is based on the idea that if the system is not broken it does not need fixing. The current system of courts martial and Defence Force magistrates (reintroduced after the High Court struck down the Australian Military Court in Lane v Morrison2), has certainly survived a number of constitutional challenges in the High Court – although often with strong dissents. The strength of those dissents, the continued shifts of opinion within the High Court, and the absence of a clear and coherent consensus within that Court on the extent to which the specific constitutional powers relied upon by the Commonwealth3 can support a military justice system operating outside Chapter III of the Commonwealth Constitution, means that the validity of the current system is assumed rather than assured. -

Chapter One the Seven Pillars of Centralism: Federalism and the Engineers’ Case

Chapter One The Seven Pillars of Centralism: Federalism and the Engineers’ Case Professor Geoffrey de Q Walker Holding the balance: 1903 to 1920 The High Court of Australia’s 1920 decision in the Engineers’ Case1 remains an event of capital importance in Australian history. It is crucial not so much for what it actually decided as for the way in which it switched the entire enterprise of Australian federalism onto a diverging track, that carried it to destinations far removed from those intended by the generation that had brought the Federation into being. Holistic beginnings. How constitutional doctrine developed through the Court’s decisions from 1903 to 1920 has been fully described elsewhere, including in a paper presented at the 1995 conference of this society by John Nethercote.2 Briefly, the original Court comprised Chief Justice Griffith and Justices Barton and O’Connor, who had been leaders in the federation movement and authors of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution. The starting-point of their adjudicative philosophy was the nature of the Constitution as an enduring instrument of government, not merely a British statute: “The Constitution Act is not only an Act of the Imperial legislature, but it embodies a compact entered into between the six Australian colonies which formed the Commonwealth. This is recited in the Preamble to the Act itself”.3 Noting that before Federation the Colonies had almost unlimited powers,4 the Court declared that: “In considering the respective powers of the Commonwealth and the States it is essential to bear in mind that each is, within the ambit of its authority, a sovereign State”.5 The founders had considered Canada’s constitutional structure too centralist,6 and had deliberately chosen the more decentralized distribution of powers used in the Constitution of the United States. -

Murdoch University School of Law Michael Olds This Thesis Is

Murdoch University School of Law THE STREAM CANNOT RISE ABOVE ITS SOURCE: THE PRINCIPLE OF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT INFORMING A LIMIT ON THE AMBIT OF THE EXECUTIVE POWER OF THE COMMONWEALTH Michael Olds This thesis is presented in fulfilment of the requirements of a Bachelor of Laws with Honours at Murdoch University in 2016 Word Count: 19,329 (Excluding title page, declaration, copyright acknowledgment, abstract, acknowledgments and bibliography) DECLARATION This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any other University. Further, to the best of my knowledge or belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text. _______________ Michael Olds ii COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGMENT I acknowledge that a copy of this thesis will be held at the Murdoch University Library. I understand that, under the provisions of s 51(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), all or part of this thesis may be copied without infringement of copyright where such reproduction is for the purposes of study and research. This statement does not signal any transfer of copyright away from the author. Signed: ………………………………… Full Name of Degree: Bachelor of Laws with Honours Thesis Title: The stream cannot rise above its source: The principle of Responsible Government informing a limit on the ambit of the Executive Power of the Commonwealth Author: Michael Olds Year: 2016 iii ABSTRACT The Executive Power of the Commonwealth is shrouded in mystery. Although the scope of the legislative power of the Commonwealth Parliament has been settled for some time, the development of the Executive power has not followed suit. -

Australian Law Reform Commission the Judicial Power of The

Australian Law Reform Commission Discussion Paper 64 The judicial power of the Commonwealth A review of the Judiciary Act 1903 and related legislation You are invited to make a submission or comment on this Discussion Paper DP 64 December 2000 How to make comments or submissions You are invited to make comments or submissions on the issues raised in this Paper, which should be sent to The Secretary Australian Law Reform Commission Level 10, 131 York Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 (GPO Box 3708 SYDNEY NSW 1044) Phone: (02) 9284 6333 TTY: (02) 9284 6379 Fax: (02) 9284 6363 E-mail: [email protected] ALRC homepage: http://www.alrc.gov.au Closing date: 16 March 2001 It would be helpful if comments addressed specific issues or paragraphs in the Paper. Confidentiality Unless a submission is marked confidential, it will be made available to any person or organisation on request. If you want your submission, or any part of it, to be treated as confidential, please indicate this clearly. A request for access to a submission marked ‘confidential’ will be determined in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Cth). The Commission will include in its final report on this project a list of submissions received in response to this Paper. It may also refer to those submissions in the text of the report and other Commission publications. It may decide to publish them. If you do not want your submission or any part of it to be used in any one of these ways please indicate this clearly. © Commonwealth of Australia 2000 This work is copyright. -

The Toohey Legacy: Rights and Freedoms, Compassion and Honour

57 THE TOOHEY LEGACY: RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS, COMPASSION AND HONOUR GREG MCINTYRE* I INTRODUCTION John Toohey is a person whom I have admired as a model of how to behave as a lawyer, since my first years in practice. A fundamental theme of John Toohey’s approach to life and the law, which shines through, is that he remained keenly aware of the fact that there are groups and individuals within our society who are vulnerable to the exercise of power and that the law has a role in ensuring that they are not disadvantaged by its exercise. A group who clearly fit within that category, and upon whom a lot of John’s work focussed, were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In 1987, in a speech to the Student Law Reform Society of Western Australia Toohey said: Complex though it may be, the relation between Aborigines and the law is an important issue and one that will remain with us;1 and in Western Australia v Commonwealth (Native Title Act Case)2 he reaffirmed what was said in the Tasmanian Dam Case,3 that ‘[t]he relationship between the Aboriginal people and the lands which they occupy lies at the heart of traditional Aboriginal culture and traditional Aboriginal life’. A University of Western Australia John Toohey had a long-standing relationship with the University of Western Australia, having graduated in 1950 in Law and in 1956 in Arts and winning the F E Parsons (outstanding graduate) and HCF Keall (best fourth year student) prizes. He was a Senior Lecturer at the Law School from 1957 to 1958, and a Visiting Lecturer from 1958 to 1965. -

Australian Federalism — Fathered by a Son of Wales Public Law Wales

Australian Federalism — Fathered by a Son of Wales Public Law Wales Chief Justice Robert French AC 15 September 2016, Cardiff, Wales We live in interesting times in the history of the United Kingdom. Its people have voted to leave the European Union at a time when the devolution of legislative powers by the United Kingdom Parliament to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, a process commenced in 1998, is evolving. It is not surprising to find a good deal being written about federalism in the United Kingdom and some of that coming out of Wales. It is no doubt an interest in the possibilities of federalism engendered by the changing landscape of devolution that has led to your invitation to me to speak about it, at least from an Australian perspective. Wales is a good place for an Australian to speak on that topic because one of the fathers of the Australian Federation, Samuel Griffith, was born not far from here at Merthyr Tydfil in 1845. His family migrated to Brisbane in the colony of New South Wales in 1853. In 1859 the colony of Queensland was carved out of New South Wales. Griffith rose to become the Premier of that Colony, its Chief Justice and in 1903 the first Chief Justice of Australia. Griffith was a dominant figure in the drafting of the Australian Constitution in 1891 when the first Convention of delegates from the Australian colonies met for that purpose. It is an interesting footnote to Australian constitutional history that in November 1890, a few months before that Convention, as Premier of Queensland he proposed by way of motion in the Queensland Legislative Assembly a federal constitution for that colony involving the creation of three provinces. -

The Religion Clauses and Freedom of Speech in Australia and the United States: Incidental Restrictions and Generally Applicable Laws

University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law Faculty Scholarship Francis King Carey School of Law Faculty 1997 The Religion Clauses and Freedom of Speech in Australia and the United States: Incidental Restrictions and Generally Applicable Laws David S. Bogen University of Maryland School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/fac_pubs Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Digital Commons Citation Bogen, David S., "The Religion Clauses and Freedom of Speech in Australia and the United States: Incidental Restrictions and Generally Applicable Laws" (1997). Faculty Scholarship. 684. https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/fac_pubs/684 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Francis King Carey School of Law Faculty at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RELIGION CLAUSES AND FREEDOM OF SPEECH IN AUSTRALIA AND THE UNITED STATES: INCIDENTAL RESTRICTIONS AND GENERALLY APPLICABLE LAWS DavidS. Bogen* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ....................................................................................... 54 II. Australian Constitutional Guarantees for Religion and Speech ....... 55 A. Section 116 of the Australian Constitution ................................ 57 B. The Implied Freedom of Political Discussion ............................ 63 1. The Implication of an Implied Freedom .............................. 64 2. 1997: Lange, Kruger, and Levy .......................................... 69 3. The Standards for Determining a Violation ........................ 75 a. The Legitimate Objective Test.. .................................... 75 b. Proportionality and the "Appropriate and Adapted" Test .............................................................. -

Jurisdiction, Granted Special Leave to Appeal, Refused Special Leave to Appeal and Not Proceeding Or Vacated

HIGH COURT BULLETIN Produced by the Legal Research Officer, High Court of Australia Library [2012] HCAB 08 (24 August 2012) A record of recent High Court of Australia cases: decided, reserved for judgment, awaiting hearing in the Court's original jurisdiction, granted special leave to appeal, refused special leave to appeal and not proceeding or vacated 1: Cases Handed Down ..................................... 3 2: Cases Reserved ............................................ 8 3: Original Jurisdiction .................................... 30 4: Special Leave Granted ................................. 32 5: Cases Not Proceeding or Vacated .................. 40 6: Special Leave Refused ................................. 41 SUMMARY OF NEW ENTRIES 1: Cases Handed Down Case Title Public Service Association of South Australia Administrative Law Incorporated v Industrial Relations Commission of South Australia & Anor J T International SA v Commonwealth of Constitutional Law Australia; British American Tobacco Australasia Limited & Ors v Commonwealth of Australia – Orders Only RCB as Litigation Guardian of EKV, CEV, CIV Constitutional Law and LRV v The Honourable Justice Colin James Forrest, One of the Judges of the Family Court of Australia & Ors – Orders Only Baker v The Queen Criminal Law Douglass v The Queen – Orders Only Criminal Law Patel v The Queen Criminal Law The Queen v Khazaal Criminal Law Minister for Home Affairs of the Commonwealth Extradition & Ors v Zentai & Ors [2012] HCAB 08 1 24 August 2012 Summary of New Entries Sweeney (BHNF