Constitutionally Protected Due Process and the Use of Criminal Intelligence Provisions 125

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice and Efficiency in Mega-Litigation

Justice and Efficiency in Mega-Litigation Anna Olijnyk Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Adelaide Law School The University of Adelaide October 2014 ii CONTENTS Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... ix Declaration .................................................................................................................................. x Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... xi Note on Referencing Conventions ......................................................................................... xii Part I: The Problem .................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 I Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 II Significance and Limits of the Study ........................................................................... 6 III Methodology and Structure ......................................................................................... 8 Chapter 2: Justice and Efficiency as Aims of Civil Procedure ....................................... 12 I Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

Ex Parte Young After Seminole Tribe

RESPONSE EX PARTE YOUNG AFIER SEMINOLE TRIBE DAVID P. CuRm* My message is one of calm placidity: Not to worry; Ex parte Young1 is alive and well and living in the Supreme Court. By way of background let me say that I am that rara avis, a law professor who thinks Hans v. Louisiana2 was rightly decided.3 For the reasons given by Justice Bradley,4 I am quite convinced that the Fed- eral Question Clause of Article III does not extend the judicial power to suits against nonconsenting states. That being so, it follows that the much lamented first half of the decision in Seminole Tribe v. Floridas is also right, for a long series of decisions makes abundantly clear that Congress cannot give the federal courts jurisdiction over matters outside Article 1l.6 Nor do I consider Ex parte Young, as Justice Souter does in his dissenting opinion in Seminole Tribe, as an obvious corollary of Hans.7 On the contrary, Ex parte Young squarely contradicts that de- cision. For even if sovereign immunity was only a matter of form in * Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law, University of Chicago. B.A., University of Chicago; LL.B., Harvard. This Comment is based upon remarks made during a panel discussion at the annual meeting of the Association of American Law Schools in January 1997. 1 209 U.S. 123 (1908). 2 134 U.S. 1 (1890) (holding that judicial power of United States does not extend to suits against state by one of its own citizens unless state consents to be sued). -

15. Judicial Review

15. Judicial Review Contents Summary 413 A common law principle 414 Judicial review in Australia 416 Protections from statutory encroachment 417 Australian Constitution 417 Principle of legality 420 International law 422 Bills of rights 422 Justifications for limits on judicial review 422 Laws that restrict access to the courts 423 Migration Act 1958 (Cth) 423 General corporate regulation 426 Taxation 427 Other issues 427 Conclusion 428 Summary 15.1 Access to the courts to challenge administrative action is an important common law right. Judicial review of administrative action is about setting the boundaries of government power.1 It is about ensuring government officials obey the law and act within their prescribed powers.2 15.2 This chapter discusses access to the courts to challenge administrative action or decision making.3 It is about judicial review, rather than merits review by administrators or tribunals. It does not focus on judicial review of primary legislation 1 ‘The position and constitution of the judicature could not be considered accidental to the institution of federalism: for upon the judicature rested the ultimate responsibility for the maintenance and enforcement of the boundaries within which government power might be exercised and upon that the whole system was constructed’: R v Kirby; Ex parte Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956) 94 CLR 254, 276 (Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Fullagar and Kitto JJ). 2 ‘The reservation to this Court by the Constitution of the jurisdiction in all matters in which the named constitutional writs or an injunction are sought against an officer of the Commonwealth is a means of assuring to all people affected that officers of the Commonwealth obey the law and neither exceed nor neglect any jurisdiction which the law confers on them’: Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth (2003) 211 CLR 476, [104] (Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ). -

Federal Ex Parte Temporary Relief

Denver Law Review Volume 61 Issue 4 Article 6 February 2021 Federal Ex Parte Temporary Relief Robert C. Dorr Mark Traphagen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Robert C. Dorr & Mark Traphagen, Federal Ex Parte Temporary Relief, 61 Denv. L.J. 767 (1984). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Denver Law Review at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. FEDERAL Ex PARTE TEMPORARY RELIEF ROBERT C. DORR* MARK TRAPHAGEN** INTRODUCTION The old equitable remedy of ex parte temporary relief has been resur- rected recently in federal law. Although known to English law since the twelfth century,' temporary relief without notice has enjoyed only periodic acceptance in America. For nearly a century after the federal courts were created, ex parte injunctions were prohibited by statute.2 More recently, their use was disfavored under procedural due process.3 During the last sev- eral years, however, the owners of intellectual property rights have redis- covered ex parte orders and, with the approval of many federal courts, have developed a formidable weapon to be used against infringers and counterfeiters. Misappropriators, infringers, pirates, and smugglers have made millions of dollars by the unauthorized use of valuable intellectual property rights such as trademarks, copyrights, patents, and trade secrets. The increasing caseload of federal courts has created delays which may outlast the brief lifespan of advanced technological products, such as software and video games. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 248/Friday, December 27, 2019

71714 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 248 / Friday, December 27, 2019 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION procedures for the review and clearance Department’s rulemaking process can be of guidance documents; and (3) a found at 49 CFR 5.5. Office of the Secretary General Counsel memorandum, This final rule reflects the existing ‘‘Procedural Requirements for DOT role of the Department’s Regulatory 14 CFR Parts 11, 300, and 302 Enforcement Actions’’ (February 15, Reform Task Force in the development 2019),3 which clarifies the procedural of the Department’s regulatory portfolio 49 CFR Parts 1, 5, 7, 106, 211, 389, 553, requirements governing enforcement and ongoing review of regulations. and 601 actions initiated by the Department, Established in response to Executive including administrative enforcement Order 13777, ‘‘Enforcing the Regulatory RIN 2105–AE84 proceedings and judicial enforcement Reform Agenda’’ (February 24, 2017), Administrative Rulemaking, Guidance, actions brought in Federal court. the Regulatory Reform Task Force is the and Enforcement Procedures This final rule removes the existing Department’s internal body, chaired by procedures on rulemaking, which are the Regulatory Reform Officer, tasked AGENCY: Office of the Secretary of outdated and inconsistent with current with evaluating proposed and existing Transportation (OST), U.S. Department departmental practice, and replaces regulations and making of Transportation (DOT). them with a comprehensive set of recommendations to the Secretary of ACTION: Final rule. procedures that will increase Transportation regarding their transparency, provide for more robust promulgation, repeal, replacement, or SUMMARY: This final rule sets forth a public participation, and strengthen the modification, consistent with applicable comprehensive revision and update of overall quality and fairness of the law. -

The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers

The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers Jared P. Cole Legislative Attorney December 23, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43834 The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers Summary Article III of the Constitution restricts the jurisdiction of federal courts to deciding actual “Cases” and “Controversies.” The Supreme Court has articulated several “justiciability” doctrines emanating from Article III that restrict when federal courts will adjudicate disputes. One justiciability concept is the political question doctrine, according to which federal courts will not adjudicate certain controversies because their resolution is more proper within the political branches. Because of the potential implications for the separation of powers when courts decline to adjudicate certain issues, application of the political question doctrine has sparked controversy. Because there is no precise test for when a court should find a political question, however, understanding exactly when the doctrine applies can be difficult. The doctrine’s origins can be traced to Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v. Madison; but its modern application stems from Baker v. Carr, which provides six independent factors that can present political questions. These factors encompass both constitutional and prudential considerations, but the Court has not clearly explained how they are to be applied. Further, commentators have disagreed about the doctrine’s foundation: some see political questions as limited to constitutional grants of authority to a coordinate branch of government, while others see the doctrine as a tool for courts to avoid adjudicating an issue best resolved outside of the judicial branch. Supreme Court case law after Baker fails to resolve the matter. -

The Nondelegation Doctrine: Alive and Well

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\93-2\NDL204.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-DEC-17 10:20 THE NONDELEGATION DOCTRINE: ALIVE AND WELL Jason Iuliano* & Keith E. Whittington** The nondelegation doctrine is dead. It is difficult to think of a more frequently repeated or widely accepted legal conclusion. For generations, scholars have maintained that the doctrine was cast aside by the New Deal Court and is now nothing more than a historical curiosity. In this Article, we argue that the conventional wisdom is mistaken in an important respect. Drawing on an original dataset of more than one thousand nondelegation challenges, we find that, although the doctrine has disappeared at the federal level, it has thrived at the state level. In fact, in the decades since the New Deal, state courts have grown more willing to invoke the nondelegation doctrine. Despite the countless declarations of its demise, the nondelegation doctrine is, in a meaningful sense, alive and well. INTRODUCTION .................................................. 619 R I. THE LIFE AND DEATH OF THE NONDELEGATION DOCTRINE . 621 R A. The Doctrine’s Life ..................................... 621 R B. The Doctrine’s Death ................................... 623 R II. THE STRUCTURE OF A CONSTITUTIONAL REVOLUTION ....... 626 R III. THE PERSISTENCE OF THE NONDELEGATION DOCTRINE ...... 634 R A. Success Rate .......................................... 635 R B. Pre– and Post–New Deal Comparison .................... 639 R C. Representative Cases.................................... 643 R CONCLUSION .................................................... 645 R INTRODUCTION The story of the nondelegation doctrine’s demise is a familiar one. Eighty years ago, the New Deal Court discarded this principle, and since then, this once-powerful check on administrative expansion has had no place in our constitutional canon. -

19-161 Department of Homeland Security V

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2019 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY ET AL. v. THURAISSIGIAM CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–161. Argued March 2, 2020—Decided June 25, 2020 The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) provides for the expedited removal of certain “applicants” seeking admission into the United States, whether at a designated port of entry or elsewhere. 8 U. S. C. §1225(a)(1). An applicant may avoid expedited removal by demonstrating to an asylum officer a “credible fear of persecution,” defined as “a significant possibility . that the alien could establish eligibility for asylum.” §1225(b)(1)(B)(v). An ap- plicant who makes this showing is entitled to “full consideration” of an asylum claim in a standard removal hearing. 8 CFR §208.30(f). An asylum officer’s rejection of a credible-fear claim is reviewed by a su- pervisor and may then be appealed to an immigration judge. §§208.30(e)(8), 1003.42(c), (d)(1). But IIRIRA limits the review that a federal court may conduct on a petition for a writ of habeas corpus. -

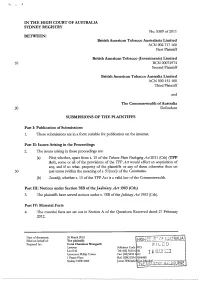

Submissions of the Plaintiffs

,, . IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA SYDNEY REGISTRY No. S389 of 2011 BETWEEN: British American Tobacco Australasia Limited ACN 002 717 160 First Plaintiff British American Tobacco (Investments) Limited 10 BCN 00074974 Second Plaintiff British American Tobacco Australia Limited ACN 000 151 100 Third Plaintiff and The Commonwealth of Australia 20 Defendant SUBMISSIONS OF THE PLAINTIFFS Part 1: Publication of Submissions 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the internet. Part II: Issues Arising in the Proceedings 2. The issues arising in these proceedings are: (a) First, whether, apart from s. 15 of the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth) (TPP Act), some or all of the provisions of the TPP Act would effect an acquisition of any, and if so what, property of the plaintiffs or any of them otherwise than on 30 just terms (within the meaning of s. 51 (xxxi) of the Constitution. (b) S econdfy, whether s. 15 of the TPP Act is a valid law of the Commonwealth. Part III: Notices under Section 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) 3. The plaintiffs have served notices under s. 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). Part IV: Material Facts 4. The material facts are set out in Section A of the Questions Reserved dated 27 February 2012. Date of document: 26 March 2012 Filed on behalf of: The plaintiffs Prepared by: Corrs Chambers Westgarth riLED Lawyers Solicitors Code 973 Level32 Tel: (02) 9210 6 00 ~ 1 "' c\ '"l , .., "2 Z 0 l';n.J\\ r_,.., I Governor Phillip Tower Fax: (02) 9210 6 11 1 Farrer Place Ref: BJW/JXM 056488 Sydney NSW 2000 JamesWhitmke -t'~r~~-~·r:Jv •,-\:' ;<()IIRNE ' 2 Part V: Plaintiffs' Argument A. -

Small Claims Standards

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS TRIAL COURT OF THE COMMONWEALTH SMALL CLAIMS STANDARDS These Standards are designed for use with Trial Court Rule III, Uniform Small Claims Rules, effective January 1, 2002, in the District Court, Boston Municipal Court, and Housing Court Departments of the Trial Court. Honorable Barbara A. Dortch-Okara Chief Justice for Administration and Management November, 2001 FOREWORD The Administrative Office of the Trial Court issues these Standards to assist judges, clerk-magistrates and other personnel of the District Court, Boston Municipal Court, and Housing Court Departments in implementing recently amended Trial Court Rule III, Uniform Small Claims Rules (effective January 1, 2002). The long delayed amendments to the Uniform Small Claims Rules were necessitated by amendments to G.L.c. 218, §§ 21-25, especially those authorizing clerk-magistrates to hear and decide small claims in the first instance, and by appellate decisions effecting procedural changes in small claims actions. The goal of the Standards is two fold: 1. To expedite, consistent with applicable statutory and decisional law and court rules, the fair and efficient disposition of small claims in all Trial Court departments having jurisdiction of such actions; and 2. To promote confidence among litigants that their small claims will be processed expeditiously and impartially by the courts according to applicable rules and statutes and recognized Standards. The Standards were carefully constructed by the Trial Court Committee on Small Claims Procedures to mesh with the amended Uniform Small Claims Rules and applicable appellate decisions. That Committee brought to its task a wealth of experience and insights gained from a variety of perspectives. -

Palmer-WA Pltf.Pdf

H I G H C O U R T O F A U S T R A L I A NOTICE OF FILING This document was filed electronically in the High Court of Australia on 23 Apr 2021 and has been accepted for filing under the High Court Rules 2004. Details of filing and important additional information are provided below. Details of Filing File Number: B52/2020 File Title: Palmer v. The State of Western Australia Registry: Brisbane Document filed: Form 27A - Appellant's submissions-Plaintiff's submissions - Revised annexure Filing party: Plaintiff Date filed: 23 Apr 2021 Important Information This Notice has been inserted as the cover page of the document which has been accepted for filing electronically. It is now taken to be part of that document for the purposes of the proceeding in the Court and contains important information for all parties to that proceeding. It must be included in the document served on each of those parties and whenever the document is reproduced for use by the Court. Plaintiff B52/2020 Page 1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA No B52 of 2020 BRISBANE REGISTRY BETWEEN: CLIVE FREDERICK PALMER Plaintiff and STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 10 Defendant PLAINTIFF’S OUTLINE OF SUBMISSIONS Clive Frederick Palmer Date of this document: 23 April 2021 Level 17, 240 Queen Street T: 07 3832 2044 Brisbane Qld 4000 E: [email protected] Plaintiff Page 2 B52/2020 -1- PART I: FORM OF SUBMISSIONS 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the Internet. PART II: ISSUES PRESENTED 2. -

Court of Australia Bill 2012 and the Military Court of Australia (Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Bill 2012

Submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs Inquiry into the Military Court of Australia Bill 2012 and the Military Court of Australia (Transitional Provisions and Consequential Amendments) Bill 2012 The purpose of this submission is to examine four key objections which have been raised to the establishment of a permanent military court in Australia in the form of the Military Court of Australia. The submission is not intended to be comprehensive, but rather seeks to consider some of the legal issues which arise in relation to these four objections.1 The authors do not consider that the first three objections are legitimate bases to reject the establishment of the Military Court of Australia, but are concerned that the fourth objection (the lack of jury trial) may give rise to a future constitutional challenge. The four objections to the establishment of a permanent military court which have been raised are as follows: 1. The establishment of a permanent court is unnecessary given that the current system is not defective This objection is based on the idea that if the system is not broken it does not need fixing. The current system of courts martial and Defence Force magistrates (reintroduced after the High Court struck down the Australian Military Court in Lane v Morrison2), has certainly survived a number of constitutional challenges in the High Court – although often with strong dissents. The strength of those dissents, the continued shifts of opinion within the High Court, and the absence of a clear and coherent consensus within that Court on the extent to which the specific constitutional powers relied upon by the Commonwealth3 can support a military justice system operating outside Chapter III of the Commonwealth Constitution, means that the validity of the current system is assumed rather than assured.