Racial Discrimination, Genocide and Reparations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional Recognition Relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Submission 394 - Attachment 1

Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Submission 394 - Attachment 1 Attachment 1 - Timeline and Overview of findings Australian Human Rights Commission Submission to the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples – July 2018 Event Summary of event / response of Social Justice Commissioner 1991 The Royal Commission Both reports state an ongoing historical connection between past racist into Aboriginal Deaths in policies and legislation and current systemic discrimination and intersecting Custody (RCIADIC) issues of disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal and Torre Strait Islander releases its report peoples. Human Rights and Equal NIRV states that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience an Opportunity Commission's endemic racism, causing serious racial violence associated with structural (HREOC) National Inquiry discrimination across Australian society. into Racist Violence (NIRV) releases its report The RCIADIC puts forward 339 recommendations. This includes developing pathways to achieving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander self- determination, and the critical need to progress reconciliation to achieve the systemic changes recommended in the report.1 The Council of Aboriginal The Act states that CAR has been established because: Reconciliation (CAR) is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples occupied Australia before established under the British settlement at Sydney Cove -

Native Title Act 1993

Legal Compliance Education and Awareness Native Title Act 1993 (Commonwealth) Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) How does the Act apply to the University? • On occasion, the University assists with Native Title claims, by undertaking research & producing reports • Work is undertaken in conjunction with ARI, Native Title representative bodies & claims groups • Representative bodies define the University’s obligations & responsibilities with respect to Intellectual Property, ethics, confidentiality & cultural respect • While these obligations are contractual, as opposed to legislative, the University would be prudent to have an understanding of the Native Title Act, how a determination of Native Title is made & the role that the Federal Court has in the management of all applications made under the Act University of Adelaide 2 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) A brief history of Native Title: Pre -colonisation • Aboriginal people & Torres Strait Islanders occupied Australia for at least 40,000 to 60,000 years before the first British colony was established in Australia • Traditional laws & customs were characterised by a strong spiritual connection to 'country' & covered things like: – caring for the natural environment and for places of significance – performing ceremonies & rituals – collecting food by hunting, fishing & gathering – providing education & passing on law & custom through stories, art, song & dance • In 1788 the British claimed sovereignty over part of Australia & established a colony University of Adelaide 3 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) A brief history of Native Title: Post-colonisation • In 1889, the British courts applied the doctrine of terra nullius to Australia, finding that as a territory that was “practically unoccupied” • In 1979, the High Court of Australia determined that Australia was indeed a territory which, “by European standards, had no civilised inhabitants or settled law” 1992 – The Mabo decision • The Mabo v Queensland (No. -

From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 19 Access to Justice: The Social Responsibility of Lawyers | Contemporary and Comparative Perspectives on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples January 2005 From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia Lisa Strelein Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa Strelein, From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia, 19 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 225 (2005), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol19/iss1/14 This Rights of Indigenous Peoples - Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Mabo to Yorta Yorta: Native Title Law in Australia Dr. Lisa Strelein* INTRODUCTION In more than a decade since Mabo v. Queensland II’s1 recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights to their traditional lands, the jurisprudence of native title has undergone significant development. The High Court of Australia decisions in Ward2 and Yorta Yorta3 in 2002 sought to clarify the nature of native title and its place within Australian property law, and within the legal system more generally. Since these decisions, lower courts have had time to apply them to native title issues across the country. This Article briefly examines the history of the doctrine of discovery in Australia as a background to the delayed recognition of Indigenous rights in lands and resources. -

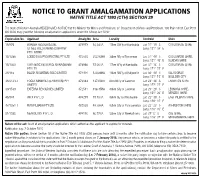

Notice to Grant Amalgamation Applications 5

attendance and improve peer relationships • Engage with families of young people involved in workshops • Maintain statistical records and data on service delivery Applications can be lodged online at • Program runs for up to 12 months Applications Now Open liveandworkhnehealth.com.au/work/ POSITION VACANT Desirable Criteria: Apply now to be part of the exciting first NSW Public opportunities-for-aboriginal-torres-strait-islander-people/ • Ability to connect and engage with young Application Information Packages are available Aboriginal and Torres Strait Service Talent Pools. people at this web address or by contacting Islander Workshop Successfully applying for a talent pool is a great way to the application kit line on (02) 4985 3150. • Experience in conducting workshops namely in be considered for a large number of roles across the Facilitator school settings • Recognised tertiary qualifications in working NSW Public Service by submitting only one application. Ward Clerk Part-Time (3 days a week, 6 hours a day) The role: with young people Administrative Support Officer Muswellbrook • Skills in delivering innovative and artistic • To provide cultural workshops with one other – Open 16 to 29 September 2015 Enquires: Dianne Prangley, (02) 6542 2042 workshops through diverse cultural and artistic Policy Officer facilitator in local schools (Mt Druitt) expression Reference ID: 279881 • Workshops aim are to engage with students – Open 28 September to 12 October 2015 To apply please send your resume by Sunday 20th Applications may close early should 500 applications and improve identification with Aboriginal Closing Date: 14 October 2015 September to: [email protected] phone Julie be received culture; involve young people in NAIDOC week celebrations, increase school retention Dubuc on 0404 087 416. -

Review of the Native Title Act 1993

Review of the Native Title Act 1993 DISCUSSION PAPER You are invited to provide a submission or comment on this Discussion Paper Discussion Paper 82 (DP 82) October 2014 This Discussion Paper reflects the law as at 1st October 2014 The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) was established on 1 January 1975 by the Law Reform Commission Act 1973 (Cth) and reconstituted by the Australian Law Reform Commission Act 1996 (Cth). The office of the ALRC is at Level 40 MLC Centre, 19 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000 Australia. Postal Address: GPO Box 3708 Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone: within Australia (02) 8238 6333 International: +61 2 8238 6333 Facsimile: within Australia (02) 8238 6363 International: +61 2 8238 6363 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.alrc.gov.au ALRC publications are available to view or download free of charge on the ALRC website: www.alrc.gov.au/publications. If you require assistance, please contact the ALRC. ISBN: 978-0-9924069-6-7 Commission Reference: ALRC Discussion Paper 82, 2014 © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in whole or part, subject to acknowledgement of the source, for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation. Requests for further authorisation should be directed to the ALRC. Making a submission Any public contribution to an inquiry is called a submission. The Australian Law Reform Commission seeks submissions from a broad cross-section of the community, as well as from those with a special interest in a particular inquiry. -

SCOTUS and the Origins of Australia's Scabrous Constitutional Signature Benjamen Franklen Guss

Br. J. Am. Leg. Studies 10(1) (2021), DOI: 10.2478/bjals-2021-0001 The Engineers Case Centenary: SCOTUS and the Origins of Australia’s Scabrous Constitutional Signature Benjamen Franklen Gussen* Sahar Araghi** ABSTRACT Since the Engineers Case decision in 1920, the role of the United States Constitution in interpreting the Australian Constitution has been diminished, leading to inefficiencies in High Court of Australia (HCA) dealing with constitutional issues. To explain this thesis, the article looks at the 7,657 cases decided by the HCA, from the first case in 1903, to the 31st of August 2020, the centenary of the Engineers Case. The analysis identifies outliers that have much higher complexity (in terms of word- length) than the other judgments. This complexity has one common denominator: comparative analysis with the United States Constitution. The article explains why this common denominator has resulted in such complexity, and concludes with possible research extensions on the roles of the Australian judiciary in embracing SCOTUS jurisprudence when interpreting the Australian Constitution. KEYWORDS High Court of Australia (HCA), Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), The Engineers Case, Constitutional Signature, Complexity CONTENTS I. Introduction ....................................................................................... 29 II. Overview of High Court Cases 1903-2020 ...................................... 31 III. First Tier Outliers .......................................................................... 33 1 -

A Regional Approach to Managing Aboriginal Land Title on Cape York1

Chapter Thirteen A Regional Approach to Managing Aboriginal Land Title on Cape York1 Paul Memmott, Peter Blackwood and Scott McDougall In 1992 the High Court of Australia for the first time gave legal recognition to the common law native title land rights of the continent's indigenous people.2 The following year the Commonwealth Government of Australia passed the Native Title Act 1993 (NTA), which introduced a statutory scheme for the recognition of native title in those areas where Aboriginal groups have been able to maintain a traditional connection to land and where the actions of governments have not otherwise extinguished their prior title. Native title as it is codified in the NTA differs from Western forms of title in three significant ways. Firstly, it is premised on the group or communal ownership of land, rather than on private property rights; secondly, it is a recognition and registration of rights and interests in relation to areas of land which pre-date British sovereignty, rather than a formal grant of title by government (QDNRM 2005: 3); thirdly, it may coexist with forms of granted statutory title, such as pastoral leases, over the same tracts of land. While native title is a formal recognition of indigenous landownership and sets up a process of registration for such interests, it remains a codification within the Western legal framework, and as such is distinct from, though related to, Aboriginal systems of land tenure as perceived by Aboriginal groups themselves. This distinction is exemplified in the sentiment often expressed by Aboriginal people that their connection to country, and the rules and responsibilities attaching to this connection, continue to apply, irrespective of the legal title of the land under `whitefellow law'. -

Exploring the Purposes of Section 75(V) of the Constitution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Australian National University 70 UNSW Law Journal Volume 34(1) EXPLORING THE PURPOSES OF SECTION 75(V) OF THE CONSTITUTION JAMES STELLIOS* I INTRODUCTION There is a familiar story told about section 75(v) of the Constitution. The story starts with the famous United States case of Marbury v Madison,1 where the Supreme Court held that it did not have jurisdiction to grant an order of mandamus directed to the Secretary of State, James Madison, to enforce the delivery of a judicial commission to William Marbury. The story continues that when Andrew Inglis Clark, who was a delegate to the 1891 Constitutional Convention, sat down to draft a constitution to be distributed to the other delegates before the Convention started, he included a provision that was to be the forerunner of section 75(v). The insertion of that provision, it is said, was intended to rectify what he saw to be a flaw in the United States Constitution exposed by the decision in Marbury v Madison. There was little discussion about the clause during the 1891 Convention, and it formed part of the 1891 draft constitution. The provision also found a place in the drafts adopted during the Adelaide and Sydney sessions of the 1897-8 Convention. However, by the time of the Melbourne session of that Convention in 1898, with Inglis Clark not a delegate, no one could remember what the provision was there for and it was struck out. -

Seeing Visions and Dreaming Dreams Judicial Conference of Australia

Seeing Visions and Dreaming Dreams Judicial Conference of Australia Colloquium Chief Justice Robert French AC 7 October 2016, Canberra Thank you for inviting me to deliver the opening address at this Colloquium. It is the first and last time I will do so as Chief Justice. The soft pink tones of the constitutional sunset are deepening and the dusk of impending judicial irrelevance is advancing upon me. In a few weeks' time, on 25 November, it will have been thirty years to the day since I was commissioned as a Judge of the Federal Court of Australia. The great Australian legal figures who sat on the Bench at my official welcome on 10 December 1986 have all gone from our midst — Sir Ronald Wilson, John Toohey, Sir Nigel Bowen and Sir Francis Burt. Two of my articled clerks from the 1970s are now on the Supreme Court of Western Australia. One of them has recently been appointed President of the Court of Appeal. They say you know you are getting old when policemen start looking young — a fortiori when the President of a Court of Appeal looks to you as though he has just emerged from Law School. The same trick of perspective leads me to see the Judicial Conference of Australia ('JCA') as a relatively recent innovation. Six years into my judicial career, in 1992, I attended a Supreme and Federal Courts Judges' Conference at which Justices Richard McGarvie and Ian Sheppard were talking about the establishment of a body to represent the common interests and concerns of judges, to defend the judiciary as an institution and, where appropriate, to defend individual judges who were the target of unfair and unwarranted criticisms. -

Of the Barrister Class by the Hon Michael Mchugh AC, Introduction

THE RISE (AND FALL?) OF THE BARRISTER CLASS BY THE HON MICHAEL McHUGH AC INTRODUCTION* The Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG As barristers go, Michael McHugh's career was unusual. There was little about it that was privileged - except his intellect and drive. Born in Newcastle, he moved with his family to North Queensland at the age of seven because his father was seeking wartime work in the mines. On his return to Newcastle, at the age of thirteen, he attended the Marist Brothers' school. There, and from his father Jim, he learned two Irish Catholic lessons that were to remain with him throughout his life in the law. First, that there are rules to be obeyed. And secondly, that civil liberties matter. To the disappointment of Jim McHugh, the young Michael left school at age fifteen. He took odd jobs, including that of the proverbial telegram boy. But his questioning intellect soon took him back to the * Notes on which were based remarks in the Common Room of the New South Wales Bar Association on 20 August 2007 on the delivery by the Hon Michael McHugh AC of a Lecture in the series on Rhetoric. 2. Hamilton High School at night. He gained his matriculation. In 1958 he commenced studies for the Barristers' Admission Board, working during the day as a clerk for the Broken Hill Proprietary Co. Michael McHugh was admitted to the New South Wales Bar in 1961. He read with two fine advocates who once frequented this common room: John Wiliams QC, himself from Newcastle, and John Kearney QC. -

Surviving Common Law: Silence and the Violence Internal to the Legal Sign

SURVIVING COMMON LAW: SILENCE AND THE VIOLENCE INTERNAL TO THE LEGAL SIGN Peter D. Rush* It is a not uncommon situation nowadays: an indigenous person comes before the common law courts in Australia and asks for a response to the demands of injustice suffered. She is a member of the stolen generations and asks for relief.1 Another is accused of a crime and questions the jurisdiction of the court to hear and determine his claim. He appears before the High Court of Australia as “Denis Bruce Walker, Bejam, Kunminarra, Jarlow, Nanaka Kabool, of Moongalba, via Goompie, Minjerribah, Quandamooka. I am the son of Oodgeroo of the tribe Noonuccal, custodian of the land Minjerribah.” He wants to be adjudged not only by the judges of the common law but also by the council of the Noonuccal. “I suspect you and your friends are trifling with me,” interjects the judge.2 Another tells the court that current as well as past and future governments are the heirs-at-law of the dispossession and death of the Wiradjuri people. Declarations recognizing aboriginal sovereignty and granting reparation for the appropriation of land and for the genocide of the Wiradjuri are requested. The High Court judge directly rejects the idea that any * Professor of Law, Law School, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia. This article was presented at the Derrida/America conference held at the Benajmin N. Cardozo School of Law, New York, February 20-21, 2005. Thank you to Nasser Hussain for extensively discussing the thesis of the article and making sure that it did not get lost in the writing, and to Tom Dumm. -

Report of the Select Committee on Native Title Rights in Western Australia

REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON NATIVE TITLE RIGHTS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA Presented by the Hon Tom Stephens MLC (Chairman) Report SELECT COMMITTEE ON NATIVE TITLE RIGHTS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA Date first appointed: 17 September 1997 Terms of Reference: (1) A Select Committee of five members is hereby appointed. Three members of the committee shall be appointed from among those members supporting the Government. (2) The mover be the Chairperson of the Committee. (3) The Committee be appointed to inquire into and report on — (a) the Federal Government’s proposed 10 Point Plan on native title rights and interests, and its impact and effect on land management in Western Australia; (b) the efficacy of current processes by which conflicts or disputes over access or use of land are resolved or determined; (c) alternative and improved methods by which these conflicts or disputes can be resolved, with particular reference to the relevance of the regional and local agreement model as a method for the resolution of conflict; and (d) the role that the Western Australian Government should play in resolution of conflict between parties over disputes in relation to access or use of land. (4) The Committee have the power to send for persons, papers and records and to move from place to place. (5) The Committee report to the House not later than November 27, 1997, and if the House do then stand adjourned the Committee do deliver its report to the President who shall cause the same to be printed by authority of this order. (6) Subject to the right of the Committee to hear evidence in private session where the nature of the evidence or the identity of the witness renders it desirable, the proceedings of the Committee during the hearing of evidence are open to accredited news media representatives and the public.