Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda 0945 Welcome Explaining the Rule of Law and Its Elements Using the Rule of Session 1: Law Pyramid

17/09/2017 WELCOME TO THE “RULE OF LAW EXPOSED” PROFESSIONAL LEARNING SEMINAR Agenda 0945 Welcome Explaining the rule of law and its elements using the rule of Session 1: law pyramid. 1015 Session 2: Explore contemporary examples, especially Racial Discrimination and Freedom of Speech. 1100 Session 3: Promoting student engagement in Years 7-10 RoLI resources and Q&A. 1125 Session 4: Teaching & Learning approaches to help understand rule of law in contexts suitable to students of both Civics & Citizenship and Politics & Law ATAR. 1145 Conclusion Q&A or WACE Student Revision Seminar for Politics & Law 1 17/09/2017 RULE OF LAW EXPOSED BY JACKIE CHARLES Please see the separate document which contains the presentation 2 17/09/2017 TEACHING & LEARNING STRATEGIES FOR CIVICS & CITIZENSHIP AS WELL AS POLITICS & LAW CIVICS & CITIZENSHIP CURRICULUM Year 7 Civics & Citizenship: the purpose and value of the Australian Constitution; the concept of the separation of powers between the legislature, executive and judiciary and how it seeks to prevent the excessive concentration of power; how Australia’s legal system aims to provide justice, including through the rule of law, presumption of innocence, burden of proof, right to a fair trial, and right to legal representation; Year 9 Civics & Citizenship: the key principles of Australia’s justice system, including equality before the law, independent judiciary, and right of appeal; Year 10 Civics & Citizenship: the role of the High Court, including interpreting the Constitution; the international agreements -

BUDGET OVERVIEW Delivering Results for South Australia

2006 07 BUDGET OVERVIEW Delivering results for South Australia BUDGET PAPER 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2006‑07 Budget at a glance _________________________________________________________ 1 Focussing on services and building communities _________________________________________ 3 Delivering infrastructure for our future __________________________________________________ 4 Public Private Partnership projects ____________________________________________________ 5 Funding our infrastructure needs ______________________________________________________ 7 Savings measures _________________________________________________________________ 8 Expenses by function and revenue by source ___________________________________________ 10 Delivering against South Australia’s Strategic Plan Improving wellbeing ____________________________________________________________ 11 Expanding opportunity __________________________________________________________ 13 Building communities ___________________________________________________________ 14 Growing prosperity ____________________________________________________________ 15 Attaining sustainability __________________________________________________________ 16 Fostering creativity ____________________________________________________________ 17 Regions ________________________________________________________________________ 18 Revenue measures _______________________________________________________________ 19 Economic highlights _______________________________________________________________ 20 Risks to fiscal outlook -

2018/05: the Barnaby Joyce Scandal: Should Ministers Be Banned From

2018/05: The Barnaby Joyce scandal: should ministers be banned from... file:///C:/dpfinal/schools/doca2018/2018sexban/2018sexban.html 2018/05: The Barnaby Joyce scandal: should ministers be banned from having affairs with parliamentary staffers? What they said... 'I certainly felt that the values I expressed and the action I took would have the overwhelming endorsement of Australians' Malcolm Turnbull, Prime Minister of Australia, commenting on his ban on sexual relations between ministers and staffers 'It's a basic principle of human rights that people can have relationships with whom they like' Ronnie Fox, a British employment law specialist from Fox and Partners The issue at a glance On February 15, 2018, the Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, made an addition to the Australian Government's 'Statement of Ministerial Standards'. The addition states, 'Ministers must not engage in sexual relations with their staff. Doing so will constitute a breach of this code.' https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/statement-ministerial-standards.pdf The addition to the Ministerial Standards came after the Daily Telegraph revealed that the Deputy Prime Minister, Barnaby Joyce, had been having a sexual relationship with his former media adviser, Vikki Campion. On February 7, 2018, the Daily Telegraph published a front page story reporting that Mr Joyce and Ms Campion were expecting a child together. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw /deputy-pm-barnaby-joyce-and-exstaffer-and-journalist-vikki-campion-expecting-a-baby/news- story/affccfbe8df768e5b9ddc9920154be6b Debate has since raged as to whether Mr Joyce had used his position to find alternative employment for Ms Campion on other ministers' staff. -

Policy Life Cycle Analysis of Three Australian State-Level Public

Article Journal of Development Policy Life Cycle Policy and Practice 6(1) 9–35, 2021 Analysis of Three © 2021 Aequitas Consulting Pvt. Ltd. and SAGE Australian State-level Reprints and permissions: in.sagepub.com/journals-permissions-india Public Policies: DOI: 10.1177/2455133321998805 Exploring the journals.sagepub.com/home/jdp Political Dimension of Sustainable Development Kuntal Goswami1,2 and Rolf Gerritsen1 Abstract This article analyses the life cycle of three Australian public policies (Tasmania Together [TT], South Australia’s Strategic Plan [SASP,] and Western Australia’s State Sustainability Strategy [WA’s SSS]). These policies were formulated at the state level and were structured around sustainable development concepts (the environmental, economic, and social dimensions). This study highlights contexts that led to the making of these public policies, as well as factors that led to their discontinuation. The case studies are based on analysis of parliamentary debates, state governments’ budget reports, public agencies’ annual reports, government media releases, and stakeholders’ feedback. The empirical findings highlight the importance of understanding the political dimension of sustainable development. This fact highlights the need to look beyond the traditional three-dimensional view of sustainability when assessing the success (or lack thereof) of sustainable development policies. Equally important, the analysis indicates that despite these policies’ limited success (and even one of these policies not being implemented at all), sustainability policies can have a legacy beyond their life cycle. Hence, the evaluation of these policies is likely to provide insight into the process of policymaking. 1 Charles Darwin University (CDU), Alice Springs, Northern Territory, Australia. 2 Australian Centre for Sustainable Development Research & Innovation (ACSDRI), Adelaide, South Australia, Australia. -

South Australia

14. South Australia Dean Jaensch South Australia was not expected to loom large in the federal election, with only 11 of the 150 seats. Of the 11, only four were marginal—requiring a swing of less than 5 per cent to be lost. Three were Liberal: Sturt (held by Christopher Pyne since 1993, 1 per cent margin), Boothby (Andrew Southcott since 1996, 3 per cent) and Grey (4.5 per cent). Of the Labor seats, only Kingston (4.5 per cent) was marginal. Table 14.1 Pre-Election Pendulum (per cent) ALP Liberal Party Electorate FP TPP Electorate FP TPP Kingston 46 .7 54 .4 Sturt 47 .2 50 .9 Hindmarsh 47 .2 55 .1 Boothby 46 .3 52 .9 Wakefield 48 .7 56 .6 Grey 47 .3 54 .4 Makin 51 .4 57 .7 Mayo 51 .1 57 .1 Adelaide 48 .2 58 .5 Barker 46 .8 59 .5 Port Adelaide 58 .2 69 .8 FP = first preference TPP = two-party preferred Labor won Kingston, Wakefield and Makin from the Liberal Party in 2007. The Liberal Party could win all three back. But, in early 2010, it was expected that if there was any change in South Australia, it would involve Liberal losses. The State election in March 2010, however, produced some shock results. The Rann Labor Government was returned to office, despite massive swings in its safe seats. In the last two weeks of the campaign, the polls showed Labor in trouble. The Rann Government—after four years of hubris, arrogance and spin—was in danger of defeat. -

Talking to Judges About the Art of Judging: an Annotated Performance Text

TALKING TO JUDGES ABOUT THE ART OF JUDGING: AN ANNOTATED PERFORMANCE TEXT Greta Bird and Nicole Rogers* [We performed this paper at the Judicial Reasoning: Art or Science? conference held at the Australian National University in February 2009. We were performing on at least two levels: as academics and editors of a collection of judicially-authored essays on the art of judging but also, as we proclaimed at the outset, as Jester and Fool. We did not appear in costume as jesters or fools. We did not even appear as fairies, although one of us is well-known at Southern Cross University for donning fairy wings and fairy tales featured in this performance (as did sheep, land rights and playfulness). But then, our audience of judges had also left their costumes behind; there were no wigs or robes. They were in civilian clothes, recognisable only as judges through name tags. They were, in fact, unmasked. Greta began by acknowledging the traditional custodians of the land. Nicole then spoke. The accompanying slide portrays a fool, colourfully clad, balanced lightly and without any apparent concern at the edge of a precipice, and a jester in classic costume.] Our focus is on judging as performance and judging as playfulness. We write as outsiders, in the guise of the Jester and the Fool: playful figures who are outside the law. Brian Sutton-Smith argues that the Fool ‘live[s] in the place where the “writ does not run”’.1 We are also influenced, however, by our role as editors of a recent collection of articles on the art of judging. -

Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Parliament in the Periphery: Sixteen Years of Labor Government in South Australia, 2002-2018* Mark Dean Research Associate, Australian Industrial Transformation Institute, Flinders University of South Australia * Double-blind reviewed article. Abstract This article examines the sixteen years of Labor government in South Australia from 2002 to 2018. With reference to industry policy and strategy in the context of deindustrialisation, it analyses the impact and implications of policy choices made under Premiers Mike Rann and Jay Weatherill in attempts to progress South Australia beyond its growing status as a ‘rustbelt state’. Previous research has shown how, despite half of Labor’s term in office as a minority government and Rann’s apparent disregard for the Parliament, the executive’s ‘third way’ brand of policymaking was a powerful force in shaping the State’s development. This article approaches this contention from a new perspective to suggest that although this approach produced innovative policy outcomes, these were a vehicle for neo-liberal transformations to the State’s institutions. In strategically avoiding much legislative scrutiny, the Rann and Weatherill governments’ brand of policymaking was arguably unable to produce a coordinated response to South Australia’s deindustrialisation in a State historically shaped by more interventionist government and a clear role for the legislature. In undermining public services and hollowing out policy, the Rann and Wethearill governments reflected the path dependency of responses to earlier neo-liberal reforms, further entrenching neo-liberal responses to social and economic crisis and aiding a smooth transition to Liberal government in 2018. INTRODUCTION For sixteen years, from March 2002 to March 2018, South Australia was governed by the Labor Party. -

Department of the Premier and Cabinet Annual Report Chief

ANNUAL REPORT 2012-2013 Department of the Premier and Cabinet State Administration Centre 200 Victoria Square Adelaide SA 5000 GPO Box 2343 Adelaide SA 5001 ISSN 0816-0813 For copies of this report please contact Finance and Business Performance Corporate Operations and Governance Division Telephone: 61 8 8226 5944 Department of the Premier and Cabinet Annual Report 2012-13 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................ 1 Chief Executive’s Review ........................................................................................................ 3 Our Organisation .............................................................................................................. 6 Achievements in 2012-13 ........................................................................................................ 9 State Government’s Seven Strategic Priorities ................................................................ 9 Three approaches to how government does business .................................................. 12 Program 1. Cabinet Office .............................................................................................. 12 Program 2. State Development ...................................................................................... 15 Program 3: Integrated Design Commission .................................................................... 17 Program 4: Capital City .................................................................................................. -

Australian Law Conference

>'-1 ·~·1;': ...::.,1·.. ', .. 't··'··lj.·' ! i ·'.c<'""r;,., ...•-F"I"R:=.s-'-'r--""=~===""""''''''=''''-====~'- ':':C-~-~;~E:~~RA; . :A-;:-~-i'?~:t9 a~ II I. I I I : I I I i I , ; ,~ > • FIRST CANADA-AUSTRALASIAN LAW CONFERENCE CANBERRA APRIL 1988 f I It is timely to note an important law conference which took place in Canberra, Australia in April 1988. The First Canada-Australasia Law Conference was held at the Australian National University in that city. organised by the Canadian , Institute for Advanced Legal Studies, the convenors of the conference were Chief Justice Nathan Nemetz of British Columbia and Justice Michael Kirby, President of the New South Wales I The conference attracted a number of leading Court of Appeal. 1 judges and practitioners from Canada, Australia, New Zealand I and the Pacific region. It was opened on 5 April 1988 by the Governor General of Australia (Sir Ninian Stephen). During the 1 conference, the Governor General hosted a dinner at Government House, Canberra, which was attended uniquely by all of the Chief Justices of Australia, who were meeting in Canberra at I the same time, all of the Chief Justices of the Superior Courtscourts f of Canada (except for the supreme court of ontario), the Chief Justices of New Zealand and Singapore and other distinguished guests. I In his opening remarks to the conference, the Chief f Justice of Canada (the Rt Han RGR G Brian Dickson PC) spoke of the need to further the links between Australian and Canadian - 1 - \ I jurisprudence. The same theme was echoed by the Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia (Sir Anthony Mason). -

Download File

SOWCmech2 12/9/99 5:29 PM Page 1 THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 e yne THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) © The Library of Congress has catalogued this serial publication as follows: Any part of THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 The state of the world’s children 2000 may be freely reproduced with the appropriate acknowledgement. UNICEF, UNICEF House, 3 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA. ISBN 92-806-3532-8 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.unicef.org UNICEF, Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland Cover photo UNICEF/92-702/Lemoyne Back cover photo UNICEF/91-0906/Lemoyne THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 Carol Bellamy, Executive Director, United Nations Children’s Fund Contents Foreword by Kofi A. Annan, Secretary-General of the United Nations 4 The State of the World’s Children 2000 Reporting on the lives of children at the end of the 20th century, The State of the World’s Children 5 2000 calls on the international community to undertake the urgent actions that are necessary to realize the rights of every child, everywhere – without exception. An urgent call to leadership: This section of The State of the World’s Children 2000 appeals to 7 governments, agencies of the United Nations system, civil society, the private sector and children and families to come together in a new international coalition on behalf of children. It summarizes the progress made over the last decade in meeting the goals established at the 1990 World Summit for Children and in keeping faith with the ideals of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. -

Submissions of the Plaintiffs

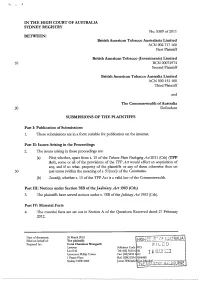

,, . IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA SYDNEY REGISTRY No. S389 of 2011 BETWEEN: British American Tobacco Australasia Limited ACN 002 717 160 First Plaintiff British American Tobacco (Investments) Limited 10 BCN 00074974 Second Plaintiff British American Tobacco Australia Limited ACN 000 151 100 Third Plaintiff and The Commonwealth of Australia 20 Defendant SUBMISSIONS OF THE PLAINTIFFS Part 1: Publication of Submissions 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the internet. Part II: Issues Arising in the Proceedings 2. The issues arising in these proceedings are: (a) First, whether, apart from s. 15 of the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth) (TPP Act), some or all of the provisions of the TPP Act would effect an acquisition of any, and if so what, property of the plaintiffs or any of them otherwise than on 30 just terms (within the meaning of s. 51 (xxxi) of the Constitution. (b) S econdfy, whether s. 15 of the TPP Act is a valid law of the Commonwealth. Part III: Notices under Section 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) 3. The plaintiffs have served notices under s. 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). Part IV: Material Facts 4. The material facts are set out in Section A of the Questions Reserved dated 27 February 2012. Date of document: 26 March 2012 Filed on behalf of: The plaintiffs Prepared by: Corrs Chambers Westgarth riLED Lawyers Solicitors Code 973 Level32 Tel: (02) 9210 6 00 ~ 1 "' c\ '"l , .., "2 Z 0 l';n.J\\ r_,.., I Governor Phillip Tower Fax: (02) 9210 6 11 1 Farrer Place Ref: BJW/JXM 056488 Sydney NSW 2000 JamesWhitmke -t'~r~~-~·r:Jv •,-\:' ;<()IIRNE ' 2 Part V: Plaintiffs' Argument A. -

Sceptical Climate Part 2: CLIMATE SCIENCE in AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPERS

October 2013 Sceptical Climate Part 2: CLIMATE SCIENCE IN AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPERS Professor Wendy Bacon Australian Centre for Independent Journalism Sceptical Climate Part 2: Climate Science in Australian Newspapers ISBN: 978-0-9870682-4-8 Release date: 30th October 2013 REPORT AUTHOR & DIRECTOR OF PROJECT: Professor Wendy Bacon (Australian Centre for Independent Journalism, University of Technology, Sydney) PROJECT MANAGER & RESEARCH SUPERVISOR: Arunn Jegan (Australian Centre for Independent Journalism) PROJECT & RESEARCH ADVISOR: Professor Chris Nash (Monash University) DESIGN AND WEB DEVELOPMENT Collagraph (http://collagraph.com.au) RESEARCHERS: Nicole Gooch, Katherine Cuttriss, Matthew Johnson, Rachel Sibley, Katerina Lebedev, Joel Rosenveig Holland, Federica Gasparini, Sophia Adams, Marcus Synott, Julia Wylie, Simon Phan & Emma Bacon ACIJ DIRECTOR: Associate Professor Tom Morton (Australian Centre for Independent Journalism, University of Technology, Sydney) ACIJ MANAGER: Jan McClelland (Australian Centre for Independent Journalism) THE AUSTRALIAN CENTRE FOR INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM The Sceptical Climate Report is a project by The Australian Centre for Independent Journalism, a critical voice on media politics, media policy, and the practice and theory of journalism. Follow ACIJ investigations, news and events at Investigate.org.au. This report is available for your use under a creative commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) license, unless specifically noted. Feel free to quote, republish, backup, and move it to whatever platform works for you. Cover graphic: Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change, 1880 - 2012. Source: NASA GISS 2 Table of Contents 1. Preface . 5 2. Key Findings. 10 3. Background Issues . 28 4. Findings 4.1 Research design and methodology. 41 4.2 Quantity of climate science coverage .