Ubuntu: Globalization, Accommodation, and Contestation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focused Ethnography: a Methodological Adaptation for Social Research in Emerging Contexts

Volume 16, No. 1, Art. 1 January 2015 Focused Ethnography: A Methodological Adaptation for Social Research in Emerging Contexts Sarah Wall Key words: Abstract: Ethnography is one of the oldest qualitative methods, yet increasingly, researchers from focused various disciplines are using and adapting ethnography beyond its original intents. In particular, a ethnography; form of ethnography known as "focused ethnography" has emerged. However, focused ethnography; ethnography remains underspecified methodologically, which has contributed to controversy about methodology; its essential nature and value. Nevertheless, an ever-evolving range of research settings, purposes, participant and questions require appropriate methodological innovation. Using the example of a focused observation; social ethnography conducted to study nurses' work experiences, this article will demonstrate how research particular research questions, the attributes of certain cultural groups, and the unique characteristics of specific researchers compel adaptations in ethnography that address the need for methodological evolution while still preserving the essential nature of the method. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. An Evolving Method 3. An Example of Focused Ethnography 4. Culture Revealed 4.1 Ideas, beliefs, and values 4.2 Knowledge, skills, and activities 4.3 Power and control 5. Discussion References Author Citation 1. Introduction Ethnography is one of the oldest qualitative research methods, originating in nineteenth century anthropology. Yet, researchers from various disciplines are now using and adapting ethnography beyond its origins as a result of philosophical reflections on the processes and purposes of the method. New fields of study, new kinds of questions, and new reasons for undertaking ethnographic studies have emerged, and with these, a form of ethnography known as "focused ethnography" has developed. -

Peace for Whom: Agency and Intersectionality in Post-War Bosnia and Herzegovina

Peace for Whom: Agency and Intersectionality in Post-War Bosnia and Herzegovina By Elena B. Stavrevska Submitted to Central European University Doctoral School of Political Science, Public Policy and International Relations In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Professor Michael Merlingen CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary January 2017 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis contains no materials accepted for any other degrees, in any other situation. Thesis contains no materials written and/or published by any other person, except when appropriate acknowledgement is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Elena B. Stavrevska Budapest, 09.01.2017 CEU eTD Collection i ABSTRACT Both peacebuilding practice and mainstream literature have predominantly approached the examination of post-war societies is a static and unidimensional manner, portraying events, practices, and actors as fixed in space, time, and identity. In line with that approach, peace and reconciliation have often been understood as a mirror image of the preceding war. Consequently, when the conflict is regarded as a clash between different ethnicities, peace is viewed as a state of those ethnicities coming together, which is then reflected in the decision- and policy-making processes. This understanding, using the prism of groupism whereby (ethnic) groups are analysed as the primary societal actors, ascribed with particular characteristics and agency, presupposes homogeneity of the groups in question. In so doing, it disregards the various intra-group struggles and the multiplicity of social identities beyond ethnicity. Furthermore, it also cements ethnicity as the most important, if not the only important political cleavage in the new, post-war reality. -

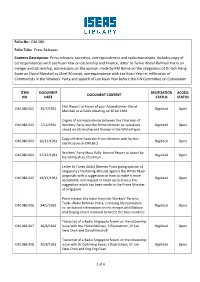

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

Economic Ascendance Is/As Moral Rightness: the New Religious Political Right in Post-Apartheid South Africa Part

Economic Ascendance is/as Moral Rightness: The New Religious Political Right in Post-apartheid South Africa Part One: The Political Introduction If one were to go by the paucity of academic scholarship on the broad New Right in the post-apartheid South African context, one would not be remiss for thinking that the country is immune from this global phenomenon. I say broad because there is some academic scholarship that deals only with the existence of right wing organisations at the end of the apartheid era (du Toit 1991, Grobbelaar et al. 1989, Schönteich 2004, Schönteich and Boshoff 2003, van Rooyen 1994, Visser 2007, Welsh 1988, 1989,1995, Zille 1988). In this older context, this work focuses on a number of white Right organisations, including their ideas of nationalism, the role of Christianity in their ideologies, as well as their opposition to reform in South Africa, especially the significance of the idea of partition in these organisations. Helen Zille’s list, for example, includes the Herstigte Nasionale Party, Conservative Party, Afrikaner People’s Guard, South African Bureau of Racial Affairs (SABRA), Society of Orange Workers, Forum for the Future, Stallard Foundation, Afrikaner Resistance Movement (AWB), and the White Liberation Movement (BBB). There is also literature that deals with New Right ideology and its impact on South African education in the transition era by drawing on the broader literature on how the New Right was using education as a primary battleground globally (Fataar 1997, Kallaway 1989). Moreover, another narrow and newer literature exists that continues the focus on primarily extreme right organisations in South Africa that have found resonance in the global context of the rise of the so-called Alternative Right that rejects mainstream conservatism. -

Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg Professor Njabulo

Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg Professor Njabulo Ndebele Honourable Former President of the Republic of South Africa and our Honorary Doctorate, Thabo Mbeki Honourable Minister of Higher Education and Training, Mrs Naledi Pandor Honourable Minister of Transport, Dr Blade Nzimande Honourable Deputy Minister of Higher Education and Training, Mr Buti Manamela Honourable Premier of Gauteng, Mr David Makhura ANC Treasurer General, Mr Paul Mashatile Former Ministers and Deputy Ministers Members of Parliament and Senior Officials from National, Provincial and Local Government Structures Former Deputy Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Professor Arthur Mutambara Honourable Ambassadors and High Commissioners Former UJ Chancellor, Ms Wendy Luhabe The Chairperson of the UJ Council, Mr Mike Teke, and current and former Members of the Council of UJ Former Vice-Chancellor, Prof Ihron Rensburg Chancellors, Chairs of Councils and Vice-Chancellors from other Universities The UJ Executive Leadership Group, Members of Senate and Distinguished Professors UJ Staff, Students and Members of the Convocation Partners from Business and Industry; Schools and Friends of UJ Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentleman Family members and friends, including my friends travelling from abroad My wife Dr. Jabulile Manana my sons Khathutshelo and Thendo as well as my daughter Denga I thank my parents who are here today Vho-Shavhani na Vho-Khathutshelo Marwala I also acknowledge the presence of my first school teacher Mrs. Netshilema who taught me in great one. I also acknowledge the presence of my high school principals and teachers Professor Matamba, Mr. Muloiwa and Mr. Lidzhade I also acknowledge the presence of my Chief Vhamusanda Vho-Ligege and her delegation It is indeed an honor for me to be leading one of the greatest and innovative universities in South Africa and beyond. -

Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee by Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S

4 Spotlight Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee By Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong declared in his eulogy at other public figures in Britain, the United States or China, the state funeral for Dr Goh Keng Swee that “Dr Goh was Dr Goh left no memoirs. However, contained within his one of our nation’s founding fathers.… A whole generation speeches and interviews are insights into how he wished of Singaporeans has grown up enjoying the fruits of growth to be remembered. and prosperity, because one of our ablest sons decided to The deepest recollections about Dr Goh must be the fight for Singapore’s independence, progress and future.” personal memories of those who had the opportunity to How do we remember a founding father of a nation? Dr interact with him. At the core of these select few are Goh Keng Swee left a lasting impression on everyone he the members of his immediate and extended family. encountered. But more importantly, he changed the lives of many who worked alongside him and in his public career initiated policies that have fundamentally shaped the destiny of Singapore. Our primary memories of Dr Goh will be through an awareness and understanding of the post-World War II anti-colonialist and nationalist struggle for independence in which Dr Goh played a key, if backstage, role until 1959. Thereafter, Dr Goh is remembered as the country’s economic and social architect as well as its defence strategist and one of Lee Kuan Yew’s ablest and most trusted lieutenants in our narrating of what has come to be recognised as “The Singapore Story”. -

31 May 1995 CONSTITUTIONAL ASSEMBLY NATIONAL

31 May 1995 CONSTITUTIONAL ASSEMBLY NATIONAL WORKSHOP AND PUBLIC HEARING FOR WOMEN - 2-4 JUNE 1995 The Council's representative at the abovementioned hearing will be Mrs Eva Mahlangu, a teacher at the Filadelfia Secondary School for children with disabilities, Eva has a disability herself. We thank you for the opportunity to comment. It is Council's opinion that many women are disabled because of neglect, abuse and violence and should be protected. Further more Women with Disabilities are one of the most marginalised groups and need to be empowered to take their rightful place in society. According to the United Nations World Programme of Action Concerning Disable Persons: "The consequences of deficiencies and disablement are particularly serious for women. There are a great many countries where women are subjected to social, cultural and economic disadvantages which impede their access to, for example, health care, education, vocational training and employment. If, in addition, they are physically or mentally disabled their chances of overcoming their disablement are diminished, which makes it all the more difficult for them to take part in community life. In families, the responsibility for caring for a disabled parent often lies with women, which considerably limits their freedom and their possibilities of taking part in other activities". The Nairobi Plan of Action for the 1990's also states: Disabled women all over the world are subject to dual discrimination: first, their gender assigns them second-class citizenship; then they are further devalued because of the negative and limited ways the world perceives people with disabilities. Legislation shall guarantee the rights of disabled women to be educated and make decisions about pregnancy, motherhood, adoption, and any medical procedure which affects their ability to reproduce. -

Critical Ethnography for School and Community

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Federation ResearchOnline CRITICAL ETHNOGRAPHY FOR SCHOOL AND COMMUNITY RENEWAL AROUND SOCIAL CLASS DIFFERENCES AFFECTING LEARNING John Smyth, Lawrence Angus, Barry Down, Peter McInerney Understanding and exploring complex and protracted social questions requires sophisticated investigative approaches. In this article we intend looking at a research approach capable of providing a better understanding of what is going on in schools, students and communities in “exceptionally challenging contexts” (Harris et al., 2006)—code for schools and communities that have as a result of wider social forces, been historically placed in situations of disadvantage. Ball (2006) summarized neatly the urgent necessity for research approaches that are theoretically tuned into being able to explore and explain what Bourdieu, Chamboredon & Passeron (1991) describe as a world that is “complicated, confused, impure [and] uncertain” (p. 259). Ball’s (2006) claim is for a research approach with the “conceptual robustness” to move us beyond the moribund situation we currently find ourselves in. As he put it: “Much of what passes for educational research is hasty, presumptive, and immodest” (p.9). What is desperately needed are theoretically adroit research approaches capable of “challenging conservative orthodoxies and closure, parsimony, and simplicity”, that retain “some sense of the obduracy and complexity of the social”, and that don’t continually “overestimate our grasp on the social world and underestimate our role in its management” (p. 9). Our particular interest here is in research orientations that are up to the task of uncovering what we know to be something extremely complex and controversial going on in schools, namely how it is that schools work in ways in which “class is achieved and maintained and enacted rather than something that just is! (Ball, 2006, p. -

The Power of Heritage to the People

How history Make the ARTS your BUSINESS becomes heritage Milestones in the national heritage programme The power of heritage to the people New poetry by Keorapetse Kgositsile, Interview with Sonwabile Mancotywa Barbara Schreiner and Frank Meintjies The Work of Art in a Changing Light: focus on Pitika Ntuli Exclusive book excerpt from Robert Sobukwe, in a class of his own ARTivist Magazine by Thami ka Plaatjie Issue 1 Vol. 1 2013 ISSN 2307-6577 01 heritage edition 9 772307 657003 Vusithemba Ndima He lectured at UNISA and joined DACST in 1997. He soon rose to Chief Director of Heritage. He was appointed DDG of Heritage and Archives in 2013 at DAC (Department of editorial Arts and Culture). Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa He studied Law at the University of Transkei elcome to the Artivist. An artivist according to and was a student activist, became the Wikipedia is a portmanteau word combining youngest MEC in Arts and Culture. He was “art” and “activist”. appointed the first CEO of the National W Heritage Council. In It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M.K. Asante. Jr Asante writes that the artivist “merges commitment to freedom and Thami Ka Plaatjie justice with the pen, the lens, the brush, the voice, the body He is a political activist and leader, an and the imagination. The artivist knows that to make an academic, a historian and a writer. He is a observation is to have an obligation.” former history lecturer and registrar at Vista University. He was deputy chairperson of the SABC Board. He heads the Pan African In the South African context this also means that we cannot Foundation. -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

4 Chapter Four: the African Ubuntu Philosophy

4 CHAPTER FOUR: THE AFRICAN UBUNTU PHILOSOPHY A person is a person through other persons. None of us comes into the world fully formed. We would not know how to think, or walk, or speak, or behave as human beings unless we learned it from other human beings. We need other human beings in order to be human. (Tutu, 2004:25). 4.1 INTRODUCTION Management practices and policies are not an entirely internal organisational matter, as various factors beyond the formal boundary of an organisation may be at least equally influential in an organisation’s survival. In this study, society, which includes the local community and its socio-cultural elements, is recognised as one of the main external stakeholders of an organisation (see the conceptual framework in Figure 1, on p. 7). Aside from society, organisations are linked to ecological systems that provide natural resources as another form of capital. As Section 3.5.13 shows, one of the most important limitations of the Balanced Scorecard model is that it does not integrate socio-cultural dimensions into its conceptual framework (Voelpel et al., 2006:51). The model’s perspectives do not explicitly address issues such as the society or the community within which an organisation operates. In an African framework, taking into account the local socio-cultural dimensions is critical for organisational performance and the ultimate success of an organisation. Hence, it is necessary to review this component of corporate performance critically before effecting any measures, such as redesigning the generic Balanced Scorecard model. This chapter examines the first set of humanist performance systems, as shown in Figure 11, overleaf. -

Famouscharacters

F A M O U S C H A R A C T E R S O R L A N D O B L O O M Orlando Jonathan Blanchard Bloom is an known celebrities. In 2002, he was chosen as English actor. He was born in Canterbury, Kent one of the Teen People "25 Hottest Stars Under on 13 January 1977. During his childhood, 25" and was named People's hottest Hollywood Bloom was told that his father was his mother's bachelor in the magazine's 2004 list. Bloom has husband, Jewish South African-born anti- also won other awards, including European Apartheid novelist Harry Saul Bloom, but when Film Awards, Hollywood Festival Award, he was thirteen (nine years after Harry's death), Empire Awards and Teen Choice Awards, and Bloom's mother revealed to him that his has been nominated for many others. biological father was actually Colin Stone, his mother's partner and family friend. Stone, the Bloom has said that he tries "not to exclude principal of the Concorde International language [himself] from real life as much as possible" .He school, was made Orlando Bloom's legal has been married to Miranda Kerr, an guardian after Harry Bloom's death. Australian model. She gave birth to a son, Flynn Christopher Blanchard Copeland Bloom, on 6 As a child, he managed to get through The January 2011 in Los Angeles. He is King's School Canterbury and St Edmund's a Manchester United fan and likes sports. School in Canterbury despite his dyslexia. He was encouraged by his mother to take art and drama classes.