About Satara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vitthal- Rukmini Temple at Deur, Satara

Vaishnavism in South‐Western Maharashtra: Vitthal‐ Rukmini Temple at Deur, Satara Ganesh D. Bhongale1 1. Department of A.I.H.C. and Archaeology, Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute, Pune – 411 006, Maharashtra, India (Email: ganeshbhongale333@ gmail.com) Received: 29 August 2018; Revised: 03 October 2018; Accepted: 12 November 2018 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 6 (2018): 720‐738 Abstract: The present paper highlights a temple which is not discussed in the realm of the Vaishnavite tradition of Early Medieval South‐Western Maharashtra. If we delve further in the nature of Brahmanism during this period, Shaivism was in its fully developed form in that region as compared to rare occurrence of Viṣṇu temples. The temple discussed here stands on high platform pertaining exterior and interior plain walls and decorative pillars with diverse iconography. This temple is perhaps a rare example where the iconographic combination of Hayagriva and Surya is depicted, hinting at the possibility of prevalence of joint worship of Hayagriva and Surya. The prominent nature of Vaishnavite iconography suggests that this temple is associated with Viṣṇu. It is rare to find independent Viṣnụ temple during this period, hence this temple is probably the only temple of Visṇ ̣u in South‐Western Maharashtra. Keywords: Vaishnavism, Vitthal‐Rukmini Temple, Satara, Maharashtra, Surya, Hayagriva, Krishna Introduction The region of south‐western Maharashtra forms an important geographical entity of western Deccan. This region has witnessed a political presence of all important Early Medieval dynasties. Their presence can be testified through their written records and monumental activities. The period onwards, 10th century CE observed to be the period of large‐scale building activity of the temples in this region and elsewhere in Maharashtra. -

Rural Satara Transaction Wise Details.Xlsx

Final List Of AAPLE SARKAR SEVA KENDRA Applied For Computer Sr.NO Name OF Applicant Taluka CSC Y/N CSC ID Education Status Remark Village Certificate SATARA TALUKA RURAL ( Total Application Received 36 *Qualified 18 Disqualified 18 * ) 1 Amit Shivdas Dalavi Aasangav Satara Yes 253134330010 12th MSCIT Qualified 2 Rupesh Vilas Shitole Ambewadi Satara Yes 744765710016 BE Comp BE Comp Qualified 3 Suvarna (Swati) Sandip Kumbhar Bhondawade Satara Yes 645452570013 12th MSCIT Qualified 4 Rajesh Vijay Jadhav Bhondawade Satara Yes 277244450011 BA MSCIT Qualified 5 Rahul Anantrao Sawant Degaon Satara Yes 331275360018 12th MSCIT Qualified 6 Akshay Laxman Khedkar Jaitapur Satara No 10 th MSCIT Qualified Khed(Sangamnag 7 Rachana Rajendra Supekar Satara Yes 563234520017 BCA MSCIT Qualified er) Kodoli(Dattanaga 8 Rohit Shrikrushna Chavan Satara Yes 143623170013 Mcom MSCIT Qualified r) 9 Aarati Hemant Dalavi Ramnagar Satara Yes 216611210017 BA MSCIT Qualified 10 Sudan Dattatray Bhosale Sambhajinagar Satara No 12 th MSCIT Qualified 11 Shivprasad Mayappa Vaghmode Shahupuri Satara No Law MSCIT Qualified 12 Gitanjali Shirish Anekar Kshetra Mahuli Satara No BA MSCIT Qualified 13 Santosh Ramchandra Phalake Nigadi Tarf Satara Satara No Bsc MSCIT Qualified 14 Prashant Prakash Pawar Kodoli Satara No BA MSCIT Qualified 15 Suhas Rajendra Sabale Vaduth Satara Yes 634114270011 12th MSCIT Qualified 16 Ganesh Anandrao Dhane Vechale Satara No BA.Ded MSCIT Qualified 17 Vikram Umakant Borate Shahupuri Satara No BE Comp BE Comp Qualified 18 Shweta Hari Jadhav Shahupuri -

Chapter - II GEOGRAPHICAL SETTING of the STUDY REGION

Chapter - II GEOGRAPHICAL SETTING OF THE STUDY REGION 2.1 introduction 2.2 Location 2.3 Boundaries 2,4 Physiography 2.5 Drainage 2.6 Climate 2.7 Forest 2.8 Soils 2.9 Landuse Pattern 2.10 Agriculture 2.11 Irrigation 2.12 Population Characteristics 2.13 Occupational Structure 2.14 Transport And Communication 2.15 Economic status of Koregaon Taluka v______________________________________________________ y 6 Chapter - O 'Geographical Setting of The Study Region' 2.1 INTRODUCTION - The geographical setting of any region is an important aspect, which plays a significant role not in influencing its past history but also the climate, landuse, means of transportation, distribution of settlements and distribution of population etc. Therefore, the study of geographical setting in relation to man and his needs are vital. (Gopal Singh, 1983). Although the study of Physical elements deal with natural Phenomena, People are always involved as evaluators, users and modifiers. When people till soil, irrigate a crop, extract a mineral deposite or foul streams, starve from drought, clear the forests from half of continent, Pour toxious gases into the air, introduce new crops into the region or avoid huge sections of the earth as being to costly or too trying to handle, they are living with and are a part of the Physical elements of the earth. (Raman-1994). 2.2 LOCATION - The region under study lies between 17°40' North to 18° North latitude and 74° east to 74°10 east longitude. Koregaon Taluka covers an area about 921.80 sq. kms and has a total population of 2,25,002 persons, according to 1991 census, residing into 110 rural inhabitants and three towns. -

GI Journal No. 77 1 November 30, 2015

GI Journal No. 77 1 November 30, 2015 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO.77 NOVEMBER 30, 2015 / AGRAHAYANA 09, SAKA 1936 GI Journal No. 77 2 November 30, 2015 INDEX S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Official Notices 4 2 New G.I Application Details 5 3 Public Notice 6 4 GI Applications Guledgudd Khana - GI Application No.210 7 Udupi Sarees - GI Application No.224 16 Rajkot Patola - GI Application No.380 26 Kuthampally Dhoties & Set Mundu - GI Application No.402 37 Waghya Ghevada - GI Application No.476 47 Navapur Tur Dal - GI Application No.477 53 Vengurla Cashew - GI Application No.489 59 Lasalgaon Onion - GI Application No.491 68 Maddalam of Palakkad (Logo) - GI Application No.516 76 Brass Broidered Coconut Shell Craft of Kerala (Logo) - GI 81 Application No.517 Screw Pine Craft of Kerala (Logo) - GI Application No.518 89 6 General Information 94 7 Registration Process 96 GI Journal No. 77 3 November 30, 2015 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 77 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 30th November 2015 / Agrahayana 09th, Saka 1936 has been made available to the public from 30th November 2015. GI Journal No. 77 4 November 30, 2015 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS App.No. Geographical Indications Class Goods 530 Tulaipanji Rice 31 Agricultural 531 Gobindobhog Rice 31 Agricultural 532 Mysore Silk 24, 25 and 26 Handicraft 533 Banglar Rasogolla 30 Food Stuffs 534 Lamphun Brocade Thai Silk 24 Textiles GI Journal No. -

DENA BANK.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE South ANDAMAN Andaman,Village &P.O AND -BambooFlat(Near bambooflat NICOBAR Rehmania Masjid) BAMBOO @denaban ISLAND ANDAMAN Bambooflat ,Andaman-744103 FLAT BKDN0911514 k.co.in 03192-2521512 non-MICR Port Blair,Village &P.O- ANDAMAN Garacharma(Near AND Susan garacharm NICOBAR Roses,Opp.PHC)Port GARACHAR a@denaba ISLAND ANDAMAN Garacharma Blair-744103 AMA BKDN0911513 nk.co.in (03192)252050 non-MICR Boddapalem, Boddapalem Village, Anandapuram Mandal, ANDHRA Vishakapatnam ANANTAPU 888642344 PRADESH ANANTAPUR BODDAPALEM District.PIN 531163 R BKDN0631686 7 D.NO. 9/246, DMM GATE ANDHRA ROAD,GUNTAKAL – 08552- guntak@denaba PRADESH ANANTAPUR GUNTAKAL 515801 GUNTAKAL BKDN0611479 220552 nk.co.in 515018302 Door No. 18 slash 991 and 992, Prakasam ANDHRA High Road,Chittoor 888642344 PRADESH CHITTOOR Chittoor 517001, Chittoor Dist CHITTOOR BKDN0631683 2 ANDHRA 66, G.CAR STREET, 0877- TIRUPA@DENA PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATHI TIRUPATHI - 517 501 TIRUPATI BKDN0610604 2220146 BANK.CO.IN 25-6-35, OPP LALITA PHARMA,GANJAMVA ANDHRA EAST RI STREET,ANDHRA 939474722 KAKINA@DENA PRADESH GODAVARI KAKINADA PRADESH-533001, KAKINADA BKDN0611302 2 BANK.CO.IN 1ST FLOOR, DOOR- 46-12-21-B, TTD ROAD, DANVAIPET, RAJAHMUNDR ANDHRA EAST RAJAMUNDRY- RAJAHMUN 0883- Y@DENABANK. PRADESH GODAVARI RAJAHMUNDRY 533103 DRY BKDN0611174 2433866 CO.IN D.NO. 4-322, GAIGOLUPADU CENTER,SARPAVAR AM ROAD,RAMANAYYA ANDHRA EAST RAMANAYYAPE PETA,KAKINADA- 0884- ramanai@denab PRADESH GODAVARI TA 533005 KAKINADA BKDN0611480 2355455 ank.co.in 533018003 D.NO.7-18, CHOWTRA CENTRE,GABBITAVA RI STREET, HERO HONDA SHOWROOM LINE, ANDHRA CHILAKALURIPE CHILAKALURIPET – CHILAKALU 08647- chilak@denaban PRADESH GUNTUR TA 522616, RIPET BKDN0611460 258444 k.co.in 522018402 23/5/34 SHIVAJI BLDG., PATNAM 0836- ANDHRA BAZAR, P.B. -

MINING PLAN (To Comply Rule 31 of MMRD, 2013) (Notification Dated 18Th July 2013)

MINING PLAN (To comply Rule 31 of MMRD, 2013) (Notification dated 18th July 2013) With PROGRESSIVE MINE CLOSURE PLAN (To comply Rule 26 of MMRD, 2013) (Notification dated 18th July 2013) OF STONE QUARRY OF SOU SHANTA DADASO GAIKWAD Survey No 565/1 Part VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT STATE AREA HA Wathar Koregaon Satara Maharashtra 0.35 Ha PREPARED BY VIVEK P. NAVARE SANKALPANA OPP. SYNDICATE BANK DHAVALIMAL, PONDA GOA 403 401. 1 CERTIFICATE This to certify that the Mining Plan of Stone Quarry for an area of 0.35 Ha. in Village- Wathar , Taluka-Koregaon , District- Satara, State – Maharashtra of Sou Shanta Dadaso Gaikwad has been prepared in full consultation with me and I have understood its contents and agree to implement the same in accordance with law. Place: Date: 2 CERTIFICATE This to certify that the Progressive Mine Closure Plan of Stone Quarry for an area of 0.35 Ha. in Village- Wathar , Taluka-Koregaon , District- Koregaon, State –Maharashtra of Sou Shanta Dadaso Gaikwad has taken into consideration all statutory rules, regulation, order, made by the Central and State Government, Statutory Organization, Court etc. and wherever any specific permissions are required, the applicant will approach the concern authorities I also given an undertaking to the effect that all measures proposed in the Quarrying Plan will be implemented in a time bound manner as proposed. Place: Date: 3 INDEX Sr No. PARTICULARS PART I 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1..1 Location & Accessibility 1.1.2 Details of the area 1.1.3 Whether the area is n forest? 1.1.4 Existence of Public road/ Railway line 1.2 Topography and Drainage 1.3 Particulars of land and Title of the property 1.4 Climate and Rainfall 2.0 GENERAL 2.1 Name and address of the lessee 2.2 Status of the applicant 2.3 Type of the stone to be quarried and processed 2.4 Usage of quarried and processed material 2.5 Period of lease 2.6 Infrastructure 2.7 Explosive License 2.8 Name and address of R. -

MAHARASHTRA STATE COUNCIL of EXAMINATIONS, PUNE PRINT DATE 16/10/2016 NATIONAL MEANS CUM MERIT SCHOLARSHIP SCHEME EXAM 2016-17 ( STD - 8 Th )

MAHARASHTRA STATE COUNCIL OF EXAMINATIONS, PUNE PRINT DATE 16/10/2016 NATIONAL MEANS CUM MERIT SCHOLARSHIP SCHEME EXAM 2016-17 ( STD - 8 th ) N - FORM GENERATED FROM FINAL PROCESSED DATA EXAM DATE : 20-NOV.-2016 Page : 1 of 222 DISTRICT : 11 - MUMBAI SR. SCHOOL SCHOOL SCHOOL NAME STUDENT NO. CODE TALUKA COUNT CENTRE : 1101 FELLOWSHIP HIGH SCHOOL, AUGUST KRANTI MAIDAN, GRANT ROAD, MUMBAI UDISE : 27230100974, TALUKA ALLOCATED : 1 1141001COLABA SAU.USHADEVI P. WAGHE H. SCHOOL, COLABA MUMBAI 6 6 2 1142023DONGRI CUMMO JAFFAR SULEMAN GIRLS HIGH SCH. MUM - 3 3 3 1143002MUMBADEVI SEBASTIAN GOAN HIGH SCHOOL, ST. FRANCIS XAVIER'S MUM-2 11 4 1143016MUMBADEVI S. L. AND S. S. GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL MUMBAI -2 14 5 1144015GIRGAON FELLOWSHIP SCHOOL GRANT RD AUGUST KRANTI MARG MUMBAI - 35 1 6 1144019GIRGAON ST. COLUMBA SCHOOL GAMDEVI MUMBAI - 7 8 7 1144026GIRGAON CHIKITSAK SAMUHA SHIROLKAR HIGH SCHOOL GIRGAON MUMBAI - 4 27 8 1145017BYCULLA ANJUMAN KHAIRUL ISLAM URDU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL 2ND GHELABAI ST 12 CENTRE TOTAL 82 CENTRE : 1102 R. M. BHATTA HIGH SCHOOL, PAREL UDISE : 27230200215, TALUKA ALLOCATED : 1 1144050GIRGAON SUNDATTA HIGH SCHOOL NEW CHIKKALWADI SLEAT RD MUMBAI - 7 5 2 1145003BYCULLA SIR ELLAY KADOORI HIGH SCHOOL MAZGAON MUM - 10 8 3 1146004PAREL BENGALI EDUCATION SOCIETY HIGH SCHOOL, NAIGAON, MUMBAI- 14 5 4 1146006PAREL NAV BHARAT VIDYALAYA, PAREL M, MUMBAI- 12 3 5 1146015PAREL R. M. BHATT HIGH SCHOOL, PAREL, MUMBAI- 12 7 6 1146021PAREL ABHUDAYA EDU. ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL, KALACHOWKI, MUMBAI-33 7 7 1146022PAREL AHILYA VIDYA MANDIR, KALACHOWKI, MUMBAI- 33 31 8 1146023PAREL SHIVAJI VIDYALAYA, - KALACHOWKI, MUMBAI- 33 8 9 1146025PAREL S. -

Distance.·. from Village to ·Village JN .SA TARA DISTRICT (NORTH)

. ' . ~o~ernment o~ 'l5omllR!? . - . · ~ublft' morks Departmen' Distance.·. from Village to ·Village JN .SA TARA DISTRICT (NORTH) ~-- BARODA ~~i\~~TED AT ;~B <!OVE~NM~N;. PRB_ss 1953. TABLE OF DISTANCES ~tara District (North) . : I •• . Distance Remarks From. .' To .• in M;iles . ' ·/. • I . .' Ahir ••• . Katroshi • •• 6 - • do. ••• Shembadi • ••• ·4 - \ Abira · ... · Khandala • .., 6 do. ' ••• Lonand 8· , •·. -··· Ajnuj ... · Amberwadi ••• li • "' . /do. -~ ... Powarwadi . ... 1 ' . · · ... · Pancbagani · · Am ben all •••• 23 , •. ' . Ambavada ·· · ·..... ·Pimppda . ... 1 · Andhali ..... · Koregao~ (via Dahiw~), ... 35 ,. do. '! .... Malavadi ... 1i .. -·;{ ; ·Anewadi -..... Raigaon· .. ..... , 1 .. Anowri Shrgaon ... • •• 2, , Arala ••• ·Red • •• 20 . do. .. · Satara Road " ... 4 Arphal •.. ••• Shivthar ••• 1 , I • -Arvi ...1 Arvi Road ... s Arvi ••• Rahimatpur .. 6 . ... • • .. Asanraon . .. · Fimpode .budrak ... 4 . .. Atit ..• Arvi Road· .. ·? ' ... ... ·' . .. • do•. ••• Borgaon · . ., .. ... 4 . do•. .. ... Karad •••• • 19 . " !' . do. ••• Latne - .... ' s . .. - do. .. • •• Satara • •• '121 .. ' • . Atke t - . • •• ·Supne· · . ... 12 . .. • Atpadi · ;.. Ma.dgal::e~-------.:.::"";.s' _ __;::;._~----·6 (Bk) T~5-1 2 From To IDistance Remarks I. in Miles Aundb Bburkodi 8 do. ... Gopuj ... 5 do, . .... ~;mapur ... .361 do. Jaygaon .31 do. ... Kbarsingi ... .... do, ... Kbatav 9 do. Kumtbe .... do. ... Knroli 6 do. Nandosbi 2 do.. .... Nbavi Budruk ... 6 do• Pusesavali ,6 do. Rabimatpur 101 do, .... Satara (via Rabimatpur) 251 dol Vadgaon 8 do. ··-·· Wa,rad. .3 do, Yelvi ... 3 Banewadi Wagboli ~ 6 Bmpuri . .... Nimsod 7 Bidal Malpmangad ... 5 Belowda Sbivade .... Bbadala ·•·· Koregaon 8 Bbaratgaon ·"" B()rgaon .2 Bboli ... An!l:ori .... 9 do. .... Kbandala · . ... .6 Bbor ... Bbatgbar 3 do, PO()na .32' ~·· ••• do. .... Satara ... 45 3 -- To Distance From in Miles Remarks • Bhor Shirwal . 9 do. .Surul .. 22 do. Wai via Shirwal .o32 Bhor Post Office o,o. Poona Post Office ... 38i Bhuin Khandala .. -

Khatav, Man, Phaltan, Satara and Wai Taluka

कᴂ द्रीय भूमम जल बो셍 ड जऱ संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण मंत्राऱय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Government of India Report on AQUIFER MAPS AND GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN Khatav, Man, Phaltan, Satara and Wai Taluka Satara District, Maharashtra म鵍यक्षेत्र, नागऩरु Central Region, Nagpur Aquifer Maps and Ground Water Management Plans, 2018 Khatav, Man, Phaltan, Satara and Wai Blocks, Satara District, Maharashtra- AQUIFER MAPS AND GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT PLANS, KHATAV, MAN, PHALTAN, SATARA AND WAI BLOCKS, SATARA DISTRICT, MAHARASHTRA CONTRIBUTORS Principal Authors Anu Radha Bhatia : Senior Hydrogeologist/ Scientist-D J. R. Verma : Scientist-D Catherine Louis : Junior Hydrogeologist/ Scientist-B Supervision & Guidance P. K. Parchure : Regional Director Dr. P. K. Jain : Superintending Hydrogeologist Sourabh Gupta : Senior Hydrogeologist/ Scientist-D Hydrogeology, GIS maps and Management Plan Anu Radha Bhatia : Senior Hydrogeologist/ Scientist-D J. R. Verma : Scientist-D Catherine Louis : Junior Hydrogeologist/ Scientist-B Groundwater Exploration Catherine Louis : Junior Hydrogeologist/ Scientist-B Junaid Ahmad : Junior Hydrogeologist/ Scientist-B Chemical Analysis Dr. Devsharan Verma : Scientist B (Chemist) Dr. Rajni Kant Sharma : Scientist B (Chemist) T. Dinesh Kumar : Assistant Chemist CGWB, CR, Nagpur Aquifer Maps and Ground Water Management Plans, 2018 Khatav, Man, Phaltan, Satara and Wai Blocks, Satara District, Maharashtra- SATARA DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical Area : 10480 sq.km Administrative Divisions : Taluka – 11; Satara,Wai, Khandala, Phaltan, Mahabaleshwar, Patan, Karad, Jaoli, Koregaon, Man, Khatav. Villages : 1739 Population (2011) : 3,003,741 Normal Annual Rainfall : 301.6 mm to 5660.4 mm 2. -

Muragraj R Swami

PPRREEFFEEAASSIIBBIILLIITTYY SSTTUUDDYY FFOORR PPRROOPPOOSSEEDD BBAASSAALLTT QQUUAARRRRYY OOFF SSOOUU.. SSHHAANNTTAA DDAADDAASSOO GGAAIIKKWWAADD Executive summary Sou Shanta Dadaso Gaikwad has granted quarry lease for an area of 0.35 Hectare in Survey no 565/1 Part of Village- Wathar, Taluka Koregaon, District Satara, Maharashtra State to the Additional Collector, Satara. The said land is Private Land. For quarrying capacity of 5000 Brass per year. The major highlights of the project are: The project comes under non agriculture land. Ideally located at a distance of 22 km North East side of Umbraj. The Lease area is located northeast of the Wathar Village. No National park or wildlife sanctuary lies within the buffer zone or nearby this region. No displacements of settlement are required. No sensitive places of notified archaeological, historical or tourist importance within or nearby the buffer zone. Project Description Location: The site is located at Gut No. 565/1 Part, Wathar Kiroli, Koregaon Taluka, District Satara, and Maharashtra. The site is accessible from National Highway no 4. Land: The land provided comes under mining area approved by the government of Maharashtra. Therefore no need of human displacement is needed in the project area. The land provided for stone mining is 0.35 hectare to the project proponent. Co-ordinate: The coordinates of the plant site are latitude 17°31'50.15"N and longitude 74° 12'10.53"E Water: Water requirement of the project will be met through the water tanker and bore well which is existing in the human settlement area. Company does not exploit any other water resources or ground water; therefore no adverse impact is anticipated on water environment. -

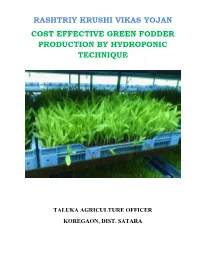

Cost Effective Green Fodder Production by Hydroponic Technique

RASHTRIY KRUSHI VIKAS YOJAN COST EFFECTIVE GREEN FODDER PRODUCTION BY HYDROPONIC TECHNIQUE TALUKA AGRICULTURE OFFICER KOREGAON, DIST. SATARA Introduction:- In Satara district Koregaon taluka comes under Dryaland and rainfed area. most of the crop production depends on rain. Annual income of farmers in this area is comparatively low. So, that it is necessary to promote dairy based farming system in this area. To overcome fodder availability problem Hydroponic fodder production technique is unique and cost efficiant than traditional fodder production method. Traditional fodder production has a number of limitations regarding soil & climatic conditions. In successful milch animal rearing green fodder has its special significance. A suitable combination of green & dry fodder is very important for maintaining animal health& milk production. But in scarcity condition traditional green fodder production become impossible because of lack of irrigation water. In such condition the technique of green fodder production by Hydroponic method is very useful tool.With this technique, it is possible to produce green fodder like Maize ,Wheat, Bajra etc. This technique does not require soil. Hence limitations like saline soil, inferior soil, water logged soil etc can be easily overcome. This technique requires very less quantity of water. Hence it can be easily undertaken in scarcity affected areas. GREEN FODDER NEED FOR CATTLE Green fodder is the natural diet of cattle. Green fodder is the most viable method to not only enhance milk production, but to also bring about a qualitative change in the milk produced by enhancing the content of unsaturated fat,, Omega 3 fatty acids , vitamins, minerals and carotenoids. Hydroponics fodder growing is the state-of-the-art technological intervention to supplement the available normal green fodder resources required by the dairy cattle. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright Potatoes, Peasants and Livelihoods: A Critical Exploration of Contract Farming and Agrarian Change in Maharashtra, India Mark R. Vicol A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Human Geography) School of Geosciences, Faculty of Science The University of Sydney 2016 ii Statement of authorship This work has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any other university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the thesis itself.