EACH-FOR Environmental Change and Forced Migration Scenarios

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H Annual Natural Disasters El Deaths

Report No.43465-TJ Report No. Tajikistan 43465-TJAnalysis Environmental Country Tajikistan Country Environmental Analysis Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized May 15, 2008 Environment Department (ENV) And Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit (ECSPE) Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... 7 IIntroduction ....................................................................................................................... 16 1. 1 Economic performance and environmental challenges ....................................... 16 1.2. Rationale ................................................................................................................... 17 1.3. Objectives ................................................................................................................. 18 1.4. Key Issues ................................................................................................................. 19 1.5, Methodology and Approach ..................................................................................... 20 1.6. Structure ofthe Rep0rt -

Wfp255696.Pdf

Summary of Findings, Methods, and Next Steps Key Findings and Issues Overall, the food security situation was analyzed in 13 livelihood zones for September–December 2012. About 870,277 people in 12 livelihood zones is classified in Phase 3- Crisis. Another 2,381,754 people are classified in Phase 2- Stressed and 2,055,402 in Phase 1- Minimal. In general, the food security status of analyzed zones has relatively improved in the reporting months compared to the previous year thanks to increased remittances received, good rainfall and good cereal production reaching 1.2 million tons, by end 2012, by 12 percent higher than in last season. The availability of water and pasture has also increased in some parts of the country, leading to improvement in livestock productivity and value. Remittances also played a major role in many household’ livelihoods and became the main source of income to meet their daily basic needs. The inflow of remittances in 2012 peaked at more than 3.5 billion USD, surpassing the 2011 record of 3.0 billion USD and accounting for almost half of the country’s GDP. Despite above facts that led to recovery from last year’s prolong and extreme cold and in improvement of overall situation, the food insecure are not able to benefit from it due to low purchasing capacity, fewer harvest and low livestock asset holding. Several shocks, particularly high food fuel prices, lack of drinking and irrigation water in many areas, unavailability or high cost of fertilizers, and animal diseases, have contributed to acute food insecurity (stressed or crisis) for thousands of people. -

Activity in Tajikistan

LIVELIHOODS άͲ͜ͲG ͞΄ͫΕ͟ ACTIVITY IN TAJIKISTAN A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) January 2011 LIVELIHOODS άͲ͜ͲG ͞΄ͫΕ͟ ACTIVITY IN TAJIKISTAN A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) January 2011 Α·͋ ̯Ϣχ·Ϊιν͛ ϭΊ͋Ϯν ͋ϳζι͋νν͇͋ ΊΣ χ·Ίν ζϢ̼ΜΊ̯̽χΊΪΣ ͇Ϊ ΣΪχ Σ͋̽͋νν̯ιΊΜϴ ι͕͋Μ͋̽χ χ·͋ ϭΊ͋Ϯν Ϊ͕ χ·͋ United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 1 Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 3 National Livelihood Zone Map and Seasonal Calendar ................................................................................ 4 Livelihood Zone 1: Eastern Pamir Plateau Livestock Zone ............................................................................ 1 Livelihood Zone 2: Western Pamir Valley Migratory Work Zone ................................................................. 3 Livelihood Zone 3: Western Pamir Irrigated Agriculture Zone .................................................................... 5 Livelihood Zone 4: Rasht Valley Irrigated Potato Zone ................................................................................. 7 Livelihood Zone 5: Khatlon Mountain Agro-Pastoral Zone .......................................................................... -

Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan Is a Document of the Borrower

Involuntary Resettlement Assessment and Measures Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Draft Project Number: September 2010 Tajikistan: CAREC Corridor 3 (Dushanbe- Uzbekistan Border) Improvement Project Prepared by the Ministry of Transport and Communications, Republic of Tajikistan The land acquisition and resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM Page No. Abbreviations and Acronyms vi Executive Summary ix 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 General 1 1.2 Requirements for LARP Finalization 1 1.3 LARP-related Project Implementation Conditions 2 1.4 Project Road Description 2 1.5 LARP Objectives 4 2.0 BASELINE INFORMATION ON LAND ACQUISTION AND RESETTLEMENT 5 2.1 General 5 2.2 Impacts 5 2.2.1 Impact on Cultivated Land 5 2.2.2 Impact on Residential and Commercial Land 5 2.2.3 Impact on Land for Community and District Government Structures 5 2.2.4 Property Status of Affected Land 6 2.2.5 Impacts on Structures and Buildings 6 2.2.6 Impacts on Annual Crops 7 2.2.7 Impacts on Perennial Crops 8 2.2.8 Business Impacts 8 2.2.9 Employment Impacts 9 2.3 Resettlement Strategy and Relocation needs 9 2.4 Census of Displaced Households/Persons Census 10 2.4.1 Total Displaced Households/Persons 10 2.4.2 Severity of Impacts 10 2.5 Impact on Vulnerable Households 10 2.5.1 Ethnic Composition of AHs 11 2.5.2 Gender 11 2.5.3 Types of Household 11 3.0 SOCIO ECONOMIC PROFILE OF THE PROJECT AREA 12 3.1 -

Agreed by Government of Tajikistan: Agreed by UNDP

United Nations Development Programme Country: Tajikistan UNDP-GEF Full Size Project (FSP) PROJECT DOCUMENT Project Title: Technology Transfer and Market Development for Small-Hydropower in Tajikistan UNDAF Outcome(s): Water, sustainable environment and energy. Expected CP Outcome(s): Outcome 6: Improved environmental protection, sustainable natural resources management, and increased access to alternative renewable energy. Expected CPAP Output (s): Output 6.2: Alternative renewable technologies including biogas, hydro, and solar power are demonstrated, understood, and widely used. Favorable policy and legal framework are established and contribute to private sector development. assist in the implementation of policies, legislation and regulations that improve market conditions for renewable energy development; demonstrate sustainable delivery models and financing mechanisms to encourage small‐scale renewable energy projects (and improve social infrastructure) and support project implementation; develop viable end‐use applications of renewable energy; and Conduct training on proper management of renewable energy systems (e.g. tariff collection) to strengthen local ownership and sustainability. Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: UNDP Tajikistan Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: Ministry of Industry and Energy Brief Description: The objective of this project is to significantly accelerate the development of small-scale hydropower (SHP) generation in Tajikistan by removing barriers through enabling legal and regulatory framework, capacity building and developing sustainable delivery models, thus substantially avoiding the use of conventional biomass and fossil fuels for power and other energy needs. The project is expected to generate global benefits in directly avoiding greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of almost 273 kilotons of CO2 due to preparation of SHP plants (over the lifetime of a SHP of 20 years) and almost 819-4,952 ktCO2 in indirect emission reductions. -

Tajikistan Republic of Tajikistan

COUNTRY REPORT ON THE STATE OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN STATE OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE (PGRFA) IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN COUNTRY REPORT BY PROF. DR. HAFIZ MUMINJANOV DUSHANBE 2008 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the Second Report on the State of World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The Report is being made available by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as requested by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. -

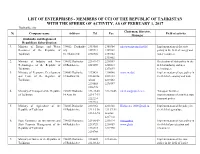

List of Enterprises

LIST OF ENTERPRISES - MEMBERS OF CCI OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN WITH THE SPHERE OF ACTIVITY, AS OF FEBRUARY 1, 2017 Dushanbe city Chairman, Director, № Company name Address Tel Fax Field of activity Manager Dushanbe and Regions of Republican Subordination 1. Ministry of Energy and Water 734012 Dushanbe 2353566 2360304 [email protected] Implementation of the state Resources of the Republic of city 2359914 2359802 policy in the field of energy and Tajikistan 5\1 Shamsi Str. 2360304 2359824 water resources 2359802 2. Ministry of Industry and New 734012 Dushanbe 221-69-97 2218889 Realization of state policy in the Technologies of the Republic of 22 Rudaki ave. 2215259 2218813 field of industry and new Tajikistan 2273697 technologies 3. Ministry of Economic Development 734002 Dushanbe 2273434 2214046 www.medt.tj Implementation of state policy in and Trade of the Republic of 37 Bokhtar Str. 2214623o 2215132 the field of economy and trade Tajikistan \about 2219463 2230668 2278597 2216778 4. Ministry of Transport of the Republic 734042 Dushanbe 221-20-03 221-20-03 [email protected]. Transport facilities, of Tajikistan 14 Ayni Str. 221-17-13 implementation of a unified state 2222214 transport policy 2222218 5. Ministry of Agriculture of the 734025 Dushanbe 2218264 2211628 [email protected] Implementation of the policy in Republic of Tajikistan 44 Rudaki Ave. 221-15-96 221-57-94 the field of agriculture 221-10-94 Isroilov 2217118 6. State Committee on Investments and 734025 Dushanbe 221-86-59 2211614 [email protected] Implementation of state policy in State Property Management of the 44 Rudaki Ave. -

DOWNLOAD 1 IPC Tajikistan Acutefi Situation

FOOD SECURITY BRIEF – TAJIKISTAN (JUNE 2013) Key Findings and Issues The food security situation was analyzed in Tajikistan’s 11 livelihood zones for the period January to May 2013, and a projection was made for the period June to October 2013. The food security status of 3 percent of the population (about 152,000 people) in rural livelihood zones was classified as Phase 3 (Crisis). The status of 39 percent of rural population (about 2,285,000 people) was classified as Phase 2 (Stressed), while the remaining 58 percent (about 3,371,000 people) was classified as Phase 1 (Minimal). In general, food security was found to have improved since the previous period (October-December 2012), with highly food insecure areas in Phase 3 (Crisis) shifting to moderately food insecure status Phase 2 (Stressed). The main contributing factors to the improvement were increased remittances, good rainfall in spring and casual labour opportunities. The seasonal availability of pasture has also led to improvement in livestock productivity and value, better food consumption pattern. Seasonally, many alternative sources of food and income became available, which includes labour planting spring crops, labor in construction work, migration, etc. Spring rains in February-March 2013 have been adequate, leading to good prospects for the cereal harvest. According to the State Statistics Agency, during the first four months of the current year, in monetary terms, agricultural production was equal to TJS 1,133.4 million and industrial production (including electricity, gas, heating) amounted TJS 2,962.0 million, which were 7.5 percent and 5.8 percent respectively higher compared to January-April 2012. -

Data Collection Survey on a Road Between Dushanbe and Kurgan-Tyube in the Republic of Tajikistan

THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON A ROAD BETWEEN DUSHANBE AND KURGAN-TYUBE IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FINAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2015 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. 3R JR 15-004 THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON A ROAD BETWEEN DUSHANBE AND KURGAN-TYUBE IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FINAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2015 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. Exchange Rate April 2015 1TJS = 21.819 Japanese Yen 1US$ = 5.45 Tajikistan Somoni 1US$ = 119.03Japanese Yen SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study The Republic of Tajikistan (hereinafter referred to as “Tajikistan”) has about 30,000km of total road network with roughly 65% of freight transport and 99% of passenger transport depending on the road network. The Dushanbe – Kurgan-Tyube road section (hereinafter referred to as the “DK road”) of the Dushanbe-Nihzny Pyanj road, connects Dushanbe with Kurgan-Tyube (one of the largest city in Khatlon). However, the opening of the Nihzny Pyanj Bridge at the border with Afghanistan has led to a dramatic increase in the traffic volume in recent years which contributed much to the deterioration of the pavement condition of this road section. Due to insufficient information, majority of the road section was not considered in the previous maintenance projects, except for the road sections that were improved under ADB financing. Under such conditions, the Tajikistan government thus considers the improvement and widening of the existing DK road as an urgent priority. This Study is undertaken to accumulate sufficient information that will be used to define the scope of work for the DK road improvement. -

Prominent Tajik Figures of the Twentieth Century

PROMINENT TAJIK FIGURES OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Dr. Iraj Bashiri Professor The University of Minnesota Dushanbe, Tajikistan 2002 Copyright © 2002 by Iraj Bashiri All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever, by photograph or mimeograph or by any other means, by broadcast or transmission,by translation into any kind of language, nor by recording electronically or otherwise,without permission in writing from the author, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in critical articles and reviews. Dushanbe, Tajikistan 2002 Acronyms and Abbreviations AIDS Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome BBC British Broadcasting Corporation CIS Commonwealth of Independent States CNR Commission for National Reconciliation CP Communist Party CPSU Communist Party of the Soviet Union CPT Communist Party of Tajikistan DPT Democratic Party of Tajikistan DSU Department of State Road Construction GES Hydroelectric Station (at Norak) GVAO (Russian) Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region GVBK (Tajik) same as GVAO HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency IMU Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan IRPT Islamic Resurgence Party of Tajikistan KGB State Security Committee KOMSOMOL Communist Youth League KPSS same as CPSU MIRT Movement for Islamic Revival in Tajikistan MSS Manuscript MTS Machine Tractor Stations RFE/RL Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty SSR Soviet Socialist Republic SSSR same as USSR STD Sexually Transmitted Diseases STE Soviet Tajik Encyclopedia STI Sexually Transmitted Infections Tajik -

Assessment of Economic Impacts from Disasters Along Key Corridors

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ASSESSMENT OF ECONOMIC IMPACTS FROM DISASTERS ALONG KEY CORRIDORS Final Report May 2021 World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized in association with: The information contained in this document is confidential, privileged and only for the information of the intended recipient and may not be used, published or redistributed without the prior written consent of IMC Worldwide Ltd. Disclaimer: This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank and the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) with external contributions. The findings, analysis and conclusions expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of any individual partner organization of The World Bank, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. Although the World Bank and GFDRR make reasonable efforts to ensure all the information presented in this document is correct, its accuracy and integrity cannot be guaranteed. The boundaries, colors, denomination, and other information shown in any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Within this study, the locations of sites with existing hazards have been determined based upon extensive site visits. These made use of official measures of the length of each road where possible. Efforts have been made to ensure that these are correct at the time of the site visit. In light of possible reconstructions or rehabilitations of the automobile roads, there is a likelihood of changes to the kilometrages of the identified hazard prone locations. -

Reduction of Winter Wheat Yield Losses Caused by Stripe Rust Through Fungicide Management Ram C

J Phytopathol ORIGINAL ARTICLE Reduction of Winter Wheat Yield Losses Caused by Stripe Rust through Fungicide Management Ram C. Sharma1, Kumarse Nazari2, Amir Amanov3, Zafar Ziyaev3 and Anwar U. Jalilov4 1 ICARDA, P.O. Box 4573, Tashkent, Uzbekistan 2 ICARDA, Rust Research Laboratory, P.O. Box 9, 35660, Izmir, Turkey 3 Uzbek Research Institute of Plant Industry, P.O. Botanika, Kibray District, Tashkent Region 111202, Uzbekistan 4 Farming Research Institute, Sharora Settlement, Hisor District, Tajikistan Keywords Abstract Central Asia, fungicide, Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, stripe rust, Triticum aestivum, Stripe rust of winter bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) causes substan- yellow rust, yield loss tial grain yield loss in Central Asia. This study involved two replicated field experiments undertaken in 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 winter Correspondence wheat crop seasons. The first experiment was conducted to determine R. C. Sharma, ICARDA, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. grain yield reductions on susceptible winter wheat cultivars using single E-mail: [email protected] and two sprays of fungicide at Zadoks growth stages Z61–Z69 in two Received: August 1, 2015; accepted: March farmers’ fields in Tajikistan and one farmer’s field in Uzbekistan. In the 25, 2016. second experiment, four different fungicides at two concentrations were evaluated at Zadoks growth stage Z69. These included three products doi: 10.1111/jph.12490 from BASF – Opus (0.5 l/ha and 1.0 l/ha), Platoon (0.5 l/ha and 1.0 l/ ha) and Opera (0.75 l/ha and 1.5 l/ha) – and locally used fungicide Titul 390 (0.5 l/ha and 1.0 l/ha).