Remarks on the Philosophical Writings of Fred Sandback

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just Deserts: the Dark Side of Moral Responsibility

(Un)just Deserts: The Dark Side of Moral Responsibility Gregg D. Caruso Corning Community College, SUNY What would be the consequence of embracing skepticism about free will and/or desert-based moral responsibility? What if we came to disbelieve in moral responsibility? What would this mean for our interpersonal re- lationships, society, morality, meaning, and the law? What would it do to our standing as human beings? Would it cause nihilism and despair as some maintain? Or perhaps increase anti-social behavior as some re- cent studies have suggested (Vohs and Schooler 2008; Baumeister, Masi- campo, and DeWall 2009)? Or would it rather have a humanizing effect on our practices and policies, freeing us from the negative effects of what Bruce Waller calls the “moral responsibility system” (2014, p. 4)? These questions are of profound pragmatic importance and should be of interest independent of the metaphysical debate over free will. As public procla- mations of skepticism continue to rise, and as the mass media continues to run headlines announcing free will and moral responsibility are illusions,1 we need to ask what effects this will have on the general public and what the responsibility is of professionals. In recent years a small industry has actually grown up around pre- cisely these questions. In the skeptical community, for example, a num- ber of different positions have been developed and advanced—including Saul Smilansky’s illusionism (2000), Thomas Nadelhoffer’s disillusionism (2011), Shaun Nichols’ anti-revolution (2007), and the optimistic skepti- cism of Derk Pereboom (2001, 2013a, 2013b), Bruce Waller (2011), Tam- ler Sommers (2005, 2007), and others. -

Fred Sandback: Sculpture and Related Work

Fred Sandback: Sculpture and Related Work University of Wyoming Art Museum, 2006 Educational Packet developed for grades K-12 Introduction In this museum visit students will view the work of the artist Fred Sandback (1943 – 2003). These seemingly simplistic works of art created from yarn are, in actuality, based on complex ideas rooted in the thinking of the group of artists know as the minimalists. Using an everyday, mundane material, Sandback set out to create art work that was sculptural, site specific and integrated into the architectural space in which it was located. The placement of his geometric forms, his use of repetition, and his consideration of color all contribute to an art form that challenges the way we think about sculpture and space. Today his wife Amy travels to galleries and museums and, using Sandback’s drawings and notes, continues to construct work based upon the shape of an architectural space. This is the work currently on display in the UW Art Museum. History Beginning in the 1960’s, the Minimalists made and exhibited three-dimensional art that explored Fred Sandback, installation view, University of Wyoming Art geometric theories and mathematical systems, such Museum, courtesy of the University of Wyoming Art Museum as proportion, symmetry, and progression. Their artwork was usually constructed from industrial materials like brick, Plexiglas, plywood and steel. They used these machine made and finished materials so that viewers couldn’t see the artist’s hand in the completed work. They did this in reaction to a group of artists from the 1950’s known as Abstract Expressionists whose works were known for incorporating and conveying intense personal emotion and expression. -

1 Realism V Equilibrism About Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU 1

Realism v Equilibrism about Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU Abstract: According to the realist about philosophy, the goal of philosophy is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions; according to what Helen Beebee calls equilibrism, by contrast, the goal is rather to place one’s commitments in a coherent system. In this paper, I present a critique of equilibrism in the form Beebee defends it, paying particular attention to her suggestion that various meta-philosophical remarks made by David Lewis may be recruited to defend equilibrism. At the end of the paper, I point out that a realist about philosophy may also be a pluralist about philosophical culture, thus undermining one main motivation for equilibrism. 1. Realism about Philosophy What is the goal of philosophy? According to the realist, the goal is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions. Do we have free will? Are morality and rationality objective? Is consciousness a fundamental feature of the world? From a realist point of view, there are truths that answer these questions, and what we are trying to do in philosophy is to come to know these truths. Of course, nobody thinks it’s easy, or at least nobody should. Looking over the history of philosophy, some people (I won’t mention any names) seem to succumb to a kind of triumphalism. Perhaps a bit of logic or physics or psychology, or perhaps just a bit of clear thinking, is all you need to solve once and for all the problems philosophers are interested in. Whether those who apparently hold such views really do is a difficult question. -

How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness

The Myth of When and Where: How False Assumptions Still Haunt Theories of Consciousness Sepehrdad Rahimian1 1 Department of Psychology, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia * Correspondence: Sepehrdad Rahimian [email protected] Abstract Recent advances in Neural sciences have uncovered countless new facts about the brain. Although there is a plethora of theories of consciousness, it seems to some philosophers that there is still an explanatory gap when it comes to a scientific account of subjective experience. In what follows, I will argue why some of our more commonly acknowledged theories do not at all provide us with an account of subjective experience as they are built on false assumptions. These assumptions have led us into a state of cognitive dissonance between maintaining our standard scientific practices on one hand, and maintaining our folk notions on the other. I will then end by proposing Illusionism as the only option for a scientific investigation of consciousness and that even if ideas like panpsychism turn out to be holding the seemingly missing piece of the puzzle, the path to them must go through Illusionism. Keywords: Illusionism, Phenomenal consciousness, Predictive Processing, Consciousness, Cartesian Materialism, Unfolding argument 1. Introduction He once greeted me with the question: “Why do people say that it was natural to think that the sun went round the earth rather than that the earth turned on its axis?” I replied: “I suppose, because it looked as if the sun went round the earth.” “Well,” he asked, “what would it have looked like if it had looked as if the earth turned on its axis?” -Anscombe, G.E.M (1963), An introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus In a 2011 paper, Anderson (2011) argued that different theories of attention suffer from somewhat arbitrary and often contradictory criteria for defining the term, rendering it more likely that we should be excluding the term “attention” from our scientific theories of the brain (Anderson, 2011). -

Illusionism As the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness

Daniel C. Dennett Illusionism as the Obvious Default Theory of Consciousness Abstract: Using a parallel with stage magic, it is argued that far from being seen as an extreme alternative, illusionism as articulated by Frankish should be considered the front runner, a conservative theory to be developed in detail, and abandoned only if it demonstrably fails to account for phenomena, not prematurely dismissed as ‘counter- intuitive’. We should explore the mundane possibilities thoroughly before investing in any magical hypotheses. Keith Frankish’s superb survey of the varieties of illusionism pro- vokes in me some reflections on what philosophy can offer to (cog- nitive) science, and why it so often manages instead to ensnarl itself in an internecine battle over details in ill-motivated ‘theories’ that, even Copyright (c) Imprint Academic 2016 if true, would be trivial and provide no substantial enlightenment on any topic, and no help at all to the baffled scientist. No wonder so For personal use only -- not for reproduction many scientists blithely ignore the philosophers’ tussles — while marching overconfidently into one abyss or another. The key for me lies in the everyday, non-philosophical meaning of the word illusionist. An illusionist is an expert in sleight-of-hand and the other devious methods of stage magic. We philosophical illusion- ists are also illusionists in the everyday sense — or should be. That is, our burden is to figure out and explain how the ‘magic’ is done. As Frankish says: Illusionism replaces the hard problem with the illusion problem — the problem of explaining how the illusion of phenomenality arises and Correspondence: Daniel C. -

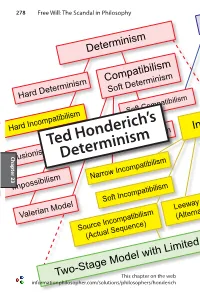

Ted Honderich's Determinism

278 Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy Determinism Indeterminism Hard Determinism Compatibilism Libertarianism Soft Determinism Hard Incompatibilism Soft Compatibilism Event-Causal Agent-Causal Chapter 23 Chapter Ted Honderich’s Illusionism DeterminismSemicompatibilism Incompatibilism SFA Non-Causal Impossibilism Narrow Incompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Causality Valerian Model Soft Incompatibilism Modest Libertarianism Soft Libertarianism Source Incompatibilism Leeway Incompatibilism Cogito Daring Soft Libertarianism (Actual Sequence) (Alternative Sequences) informationphilosopher.com/solutions/philosophers/honderichTwo-Stage Model with Limited Determinism and Limited Indeterminism This chapter on the web Ted Honderich 279 Indeterminism Ted Honderich’s Determinism DeterminismLibertarianism Ted Honderich is the principal spokesman for strict physical causality and “hard determinism.” Agent-Causal He has written more widely (with excursions into quantum Compatibilism mechanics,Event-Causal neuroscience, and consciousness), more deeply, and Soft Determinism certainly more extensively than most of his colleagues on the Hard Determinism problem of free will. Unlike most of his determinist colleagues specializingNon-Causal in free will, Honderich has notSFA succumbed to the easy path of Soft Compatibilism compatibilism by simply declaring that the free will we have (and should want, says Daniel Dennett) is completely consistent Hard Incompatibilism Incompatibilismwith determinism, namely a HumeanSoft “voluntarism” Causality or “freedom -

Smilansky-Free-Will-Illusion.Pdf

IV*—FREE WILL: FROM NATURE TO ILLUSION by Saul Smilansky ABSTRACT Sir Peter Strawson’s ‘Freedom and Resentment’ was a landmark in the philosophical understanding of the free will problem. Building upon it, I attempt to defend a novel position, which purports to provide, in outline, the next step forward. The position presented is based on the descriptively central and normatively crucial role of illusion in the issue of free will. Illusion, I claim, is the vital but neglected key to the free will problem. The proposed position, which may be called ‘Illusionism’, is shown to follow both from the strengths and from the weaknesses of Strawson’s position. We have to believe in free will to get along. C.P. Snow ir Peter Strawson’s ‘Freedom and Resentment’ (1982, first Spublished in 1962) was a landmark in the philosophical understanding of the free will problem. It has been widely influ- ential and subjected to penetrating criticism (e.g. Galen Strawson 1986 Ch.5, Watson 1987, Klein 1990 Ch.6, Russell 1995 Ch.5). Most commentators have seen it as a large step forward over previous positions, but as ultimately unsuccessful. This is where the discussion within this philosophical direction has apparently stopped, which is obviously unsatisfactory. I shall attempt to defend a novel position, which purports to provide, in outline, the next step forward. The position presented is based on the descriptively central and normatively crucial role of illusion in the issue of free will. Illusion, I claim, is the vital but neglected key to the free will problem. -

The Illusion of Realism in Film

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Philosophy Faculty Research Philosophy Department 7-2002 The Illusion of Realism in Film Andrew Kania Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/phil_faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Repository Citation Kania, A. (2002). The illusion of realism in film. British Journal of Aesthetics, 42(3), 243-258. doi:10.1093/ bjaesthetics/42.3.243 This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Illusion of Realism in Film Andrew Kania [This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The British Journal of Aesthetics following peer review. The version of record (Andrew Kania, “The Illusion of Realism in Film” British Journal of Aesthetics 42 (2002): 243-58) is available online at: http://bjaesthetics.oxfordjournals.org/content/42/3/243.abstract?sid=31bb4bc4-514f- 46ef-9efc-c7b4544506d4. Please cite only the published version.] The moviegoer’s brain, hoodwinked by this succession of still lives, obligingly infers motion. − Nicholson Baker, “The Projector”1 In “Film, Reality, and Illusion,”2 one of his many concentrated yet lucid writings on film, Gregory Currie argues, among other things, that when we watch a film we have the impression that we are seeing a ‘moving picture’ not because of an illusion perpetrated against our visual faculty, but because the images that we see up on the screen really are moving. -

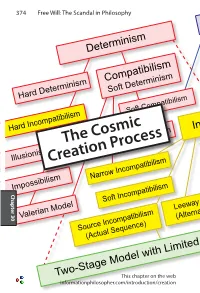

The Cosmic Creation Process 375 Indeterminism the Cosmic Creation Process Cosmic Creationlibertarianism Is Horrendously Wasteful

374 Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy Determinism Indeterminism Hard Determinism Compatibilism Libertarianism Soft Determinism Hard Incompatibilism Soft Compatibilism Event-Causal Agent-Causal The Cosmic Illusionism Semicompatibilism Creation Process Incompatibilism SFA Non-Causal Impossibilism Chapter 30 Chapter Narrow Incompatibilism Broad Incompatibilism Soft Causality Valerian Model Soft Incompatibilism Modest Libertarianism Soft Libertarianism Source Incompatibilism Leeway Incompatibilism Cogito Daring Soft Libertarianism (Actual Sequence) (Alternative Sequences) Two-Stage Model with Limited Determinism and Limited Indeterminism informationphilosopher.com/introduction/creation This chapter on the web The Cosmic Creation Process 375 Indeterminism The Cosmic Creation Process Cosmic creationLibertarianism is horrendously wasteful. In the existential Determinism balance between the forces of destruction and the forces of con- struction, there is no contest. The dark side is overwhelming. By quantitative physical measures of matter andAgent-Causal energy content, there is far more chaos than cosmos in our universe. But it is the Compatibilism cosmos that we prize. As we sawEvent-Causal in the introduction, my philosophy focuses on the Soft Determinism qualitatively valuable information structures in the universe. The Hard Determinism destructive forces are entropic, they increase the entropyNon-Causal and dis- order. The constructive forces are anti-entropic. They increase the Soft Compatibilism order and information. SFA The fundamental question of information philosophy is there- Incompatibilismfore cosmological and ultimately metaphysical. Hard Incompatibilism What creates the information structuresSoft in theCausality universe? At the starting point, the archē (ἡ ἀρχή), the origin of the Semicompatibilism universe, all was light - pure radiation, at an extraordinarily high Broad Incompatibilismtemperature. As the universe expanded, theSoft temperature Libertarianism of the Illusionism radiation fell. -

Why Does Fred Sandback's Work Make Me Cry?

Fred Sandback. Installation drawing for Dia:Beacon, Riggio Galleries, 2003. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation. 30 Why Does Fred Sandback’s Work Make Me Cry? ANDREA FRASER Language without affect is a dead language: and affect without language is uncommunicable. Language is situated between the cry and the silence. Silence often makes heard the cry of psychic pain and behind the cry the call of silence is like comfort.1 —André Green The “Greatest Generation” I first imagined this paper on the train ride home after my first visit to Dia:Beacon in May 2003. I walked around the new museum’s galleries that day with the other Sunday visitors. It was a diverse group that seemed to include art students and art professionals as well as families with strollers appearing bewildered but behaving, for the most part, in respectful con- sideration of the art of our recently proclaimed “Greatest Generation.”2 I did what I always do when I visit new museums. I noted the relative sense of a “threshold” in the entrance area and the different arrangements made for members and non- members, insiders and outsiders. I examined the wall labels. I appraised the didactics. I paced the location of the cafeteria and bookshop relative to the galleries. I measured the scale of the spaces with my body. I watched other visitors interact with the art as well as with the institution. I did all that. And I also looked at the art—more than I often do in museums, because Dia’s collection contains some of the art I love most. -

FRED SANDBACK Born 1943 in Bronxville, New York

This document was updated on April 27, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. FRED SANDBACK Born 1943 in Bronxville, New York. Died 2003 in New York, New York. EDUCATION 1957–61 Williston Academy, Easthampton, Massachusetts 1961–62 Theodor-Heuss-Gymnasium, Heilbronn 1962–66 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, BA 1966–69 Yale School of Art and Architecture, New Haven, Connecticut, MFA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1968 Fred Sandback: Plastische Konstruktionen. Konrad Fischer Galerie, Düsseldorf. May 18–June 11, 1968 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. October 24–November 17, 1968 1969 Fred Sandback: Five Situations; Eight Separate Pieces. Dwan Gallery, New York. January 4–January 29, 1969 Fred Sandback. Ace Gallery, Los Angeles. February 13–28, 1969 Fred Sandback: Installations. Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld. July 5–August 24, 1969 [catalogue] 1970 Fred Sandback. Dwan Gallery, New York. April 4–30, 1970 Fred Sandback. Galleria Françoise Lambert, Milan. Opened November 5, 1970 Fred Sandback. Galerie Yvon Lambert, Paris. Opened November 13, 1970 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. 1970 1971 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. January 27–February 13, 1971 Fred Sandback. Galerie Reckermann, Cologne. March 12–April 15, 1971 Fred Sandback: Installations; Zeichnungen. Annemarie Verna Galerie, Zurich. November 4–December 8, 1971 1972 Fred Sandback. Galerie Diogenes, Berlin. December 2, 1972–January 27, 1973 Fred Sandback. John Weber Gallery, New York. December 9, 1972–January 3, 1973 Fred Sandback. Annemarie Verna Galerie, Zürich. Opened December 19, 1972 Fred Sandback. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. 1972 Fred Sandback: Neue Arbeiten. Galerie Reckermann, Cologne. -

Illusionism As a Theory of Consciousness*

Illusionism as a Theory of Consciousness Keith Frankish So, if he’s doing it by divine means, I can only tell him this: ‘Mr Geller, you’re doing it the hard way.’ (James Randi, 1997, p. 174) Theories of consciousness typically address the hard problem. They accept that phenomenal consciousness is real and aim to explain how it comes to exist. There is, however, another approach, which holds that phenomenal consciousness is an illusion and aims to explain why it seems to exist. We might call this eliminativism about phenomenal consciousness. The term is not ideal, however, suggesting as it does that belief in phenomenal consciousness is simply a theoretical error, that rejection of phenomenal realism is part of a wider rejection of folk psychology, and that there is no role at all for talk of phenomenal properties — claims that are not essential to the approach. Another label is ‘irrealism’, but that too has unwanted connotations; illusions themselves are real and may have considerable power. I propose ‘illusionism’ as a more accurate and inclusive name, and I shall refer to the problem of explaining why experiences seem to have phenomenal properties as the illusion problem .1 Although it has powerful defenders — pre-eminently Daniel Dennett — illusionism remains a minority position, and it is often dismissed out of hand as failing to ‘take consciousness seriously’ (Chalmers, 1996). The aim of this article is to present the case for illusionism. It will not propose a detailed illusionist theory, but will seek to persuade the reader that the illusionist research programme is worth pursuing and that illusionists do take consciousness seriously — in some ways, more seriously than realists do.