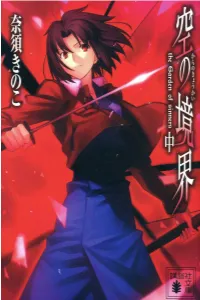

Empty Boundaries – Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aniplex of America to Release Double Feature Blu-Ray Set of the Garden

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 14, 2015 Aniplex of America to Release Double Feature Blu-ray Set of the Garden of sinners -recalled out summer- and <extra chorus> © KINOKO NASU / Seikaisha, Aniplex, Kodansha, Notes, ufotable The Final Installment of the Mega-Hit Animated Movie Series Coming to Blu-ray this April! SANTA MONICA, CA (February 14, 2015) –Fans at Katsucon (National Harbor, MD) were excited to hear Aniplex of America announce their plans to release the Garden of sinners – recalled out summer- (a.k.a Mirai Fukuin) and the Garden of sinners –recalled out summer- <extra chorus> in a Limited Edition Blu-ray Set (2-disc set) on April 21st. This will be the very last movie of the extremely popular the Garden of sinners animated movie series released 3 years after the last film, “Last Chapter: the Garden of sinners” in 2010. Pre-orders are being taken starting on February 16th on the official the Garden of sinners homepage (www.AniplexUSA.com/thegardenofsinners). Originally a seven series online novel by author Kinoko Nasu, the Garden of sinners was adapted into a feature film series with the first chapter, “Chapter 1: Thanatos” released in December of 2007 and the final chapter “Last Chapter: the Garden of sinners” released in December of 2010. The films saw great success at the Japanese box-office and broke numerous anime movie records by the seventh film. Three years after the release of the seventh film, a story not initially included in the film series, “recalled out summer” and “recalled out summer <extra chorus>” was finally adapted into a film. -

Chapter 11 Case No. 21-10632 (MBK)

Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 249 Filed 04/06/21 Entered 04/06/21 16:21:35 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 92 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY In re: Chapter 11 L’OCCITANE, INC., Case No. 21-10632 (MBK) Debtor. Judge: Hon. Michael B. Kaplan CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Ana M. Galvan, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On April 2, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: Notice of Deadline for Filing Proofs of Claim Against the Debtor L’Occitane, Inc. (attached hereto as Exhibit C) [Customized] Official Form 410 Proof of Claim (attached hereto as Exhibit D) Official Form 410 Instructions for Proof of Claim (attached hereto as Exhibit E) Dated: April 6, 2021 /s/ Ana M. Galvan Ana M. Galvan STRETTO 410 Exchange, Suite 100 Irvine, CA 92602 Telephone: 855-434-5886 Email: [email protected] Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 249 Filed 04/06/21 Entered 04/06/21 16:21:35 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 92 Exhibit A Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 249 Filed 04/06/21 Entered 04/06/21 16:21:35 Desc Main Document Page 3 of 92 Exhibit A Served via First-Class Mail Name Attention Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City State Zip Country 1046 Madison Ave LLC c/o HMH Realty Co., Inc., Rexton Realty Co. -

How Japanese Comic Books Influence Taiwanese Students A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading Comic Books Critically: How Japanese Comic Books Influence Taiwanese Students A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Fang-Tzu Hsu 2015 © Copyright by Fang-Tzu Hsu 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading Comic Books Critically: How Japanese Comic Books Influence Taiwanese Students by Fang-Tzu Hsu Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Carlos A. Torres, Chair Education knows no boundaries but hot button topics, like comic books, demonstrate school, teacher and parent limitations. Japanese comic books (manga) are a litmus test of pedagogical tolerance. Because they play an important role in the lives of most Taiwanese teenagers, I give them pride of place in this dissertation. To understand Japanese comic books and their influence, I use Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy to combine perspectives from cultural studies, comparative education, and educational sociology. With the cooperation of the administration, faculty and students of a Taiwanese junior high school, I used surveys, a textual analysis of five student-selected titles and interviews with students and educators. I discovered that Japanese manga contain complex and sometimes contradictory ideologies of ethnicity, gender, class, and violence. From an ethnic perspective, although students may glean cultural content from manga heroes and their retinues, people of color and non-Japanese Asians are either caricatures or non-existent; although Taiwanese teenager readers seem unaware of this. From a gender standpoint, neither the female characters’ provocative representation nor the male characters’ slavering responses to it raise students’ and teachers’ concerns. -

Type-Moon.Pdf

TYPE -MOON Type-Moon est une société qui a commencé comme un groupe de doujins, comptant un auteur principal, Nasu Kinoko, et un artiste principal, Takeuchi Takashi. L'auteur a établi au fil de ses œuvres un univers particulier et très vaste. Après la sorti de Tsukihime, jeu hentaï qui l'a révélée au Japon comme outre-mer à un public relativement large, Type-Moon est devenu une société professionnelle. D'autres groupes se sont associés à eux pour créer d'autres œuvres, dirigées par Nasu et poursuivant le développement de l'univers : jeux de combat, romans, drama CD, etc. On compte principalement deux « sagas » chez Type-Moon, qui sont Tsukihime et Fate ; mais d'autres œuvres gravitent également dans le même univers, que l'on surnomme le « Nasuverse ». Nous vous proposons aujourd'hui à travers ce méta-dossier de dévoiler un grand nombre des secrets de cet univers, son fonctionnement et les nombreux liens entre les séries. Pour votre plaisir, beaucoup de ces informations sont directement traduites des divers livres d'informations, qui sont légions chez Type-Moon. On note qu'en réalité, le groupe doujin Type-Moon a pris pour nom officiel Notes Y.K. (tiré d'une nouvelle de Nasu d'où vient également le nom Type-Moon) en devenant une compagnie, mais l'équipe est plus largement connue sous le nom du groupe doujin, qui est resté le logo sur leurs jeux et romans. Nasu et Takeuchi entretiennent toujours en parallèle le blog Takebōki de leur groupe de doujin. © TYPE-MOON Dossier de Byakko www.japanbar.net © 2004 - 2009 Tous droits réservés ATTENTION ! Au cours de ce grand dossier, les sections « histoire » proposeront une présentation concise de chaque œuvre avec un minimum de spoilers. -

Yokai Invasion!

Yokai Invasion! July 30-Aug 1, 2021 Coralville, Iowa Coralville Marriott Hotel and Conference Center Visit The AnimeIowa Inari Shrine! Ready for a change of pace from the convention chaos? Looking for a unique photo spot? Need to offer a special prayer to a higher power? Please join the yōkai in our peaceful Japanese garden. But beneath this idyllic setting, does the shrine harbor an ancient secret? Stop by our Marketplace location to nd out! This attraction is free to visit, but all shrine donations will benet the Iowa Asian Alliance. ~ Sponsored by AnimeIowa Labs ~ July 30-Aug 1, 2021 “Yokai Invasion!” Table of Contents Registration 03 Art Show 21 Convention Rules and Information Charity Project 21 General Behavior 04 Photoshoots 22 Harassment 04 Paneling Safety and Heath Measures 05 Schedule 23 Volunteers 06 Descriptions Accessibility 07 GoH Panels 26 Info Desk 07 Friday 27 Sponsors 08 Saturday 28 Honored Guests 09 Sunday 30 Programming Video Rooms Tabletop Gaming 15 Schedule 31 Video Gaming 17 Descriptions 33 Family Programming 18 Staff 40 Cosplay Marketplace Hall Cosplay 19 Listings 41 Masquerade Cosplay 20 Map 42 Hours of Operation Convention Hours Friday Noon - Midnight Anime Marketplace Friday 3pm - 8pm Saturday 8 am - Midnight & Artists Alley Saturday 10am - 6pm Sunday 8 am - 6 pm Sunday 10am - 4pm Opening Ceremonies Friday 1 pm - 2 pm Cosplay Central Friday 12pm - 8pm Closing Ceremonies Sunday 4 pm - 5 pm Saturday 10am - 4pm Sunday 10am - 4pm Registration Thursday 5:30 pm - 8:30 pm Masquerade Saturday 6:30pm - 9pm Friday 9:00 am - 8:00 pm At-The-Door Sat Only Available Saturday 9:00 am - 4:00 pm Reg for AI 2022 Sunday 9:00 am - 4:30 pm A Special THANK YOU to the Mindbridge Foundation You are invited to the Mindbridge Foundation is a not-for-prot corporation organized to provide a resource Mindbridge Panel on group for those interested in Science Fiction, Fantasy, and related areas. -

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5. -

![Aniplex of America Announces Fate/Stay Night [Unlimited Blade Works] Complete Blu-Ray Box Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3826/aniplex-of-america-announces-fate-stay-night-unlimited-blade-works-complete-blu-ray-box-set-3123826.webp)

Aniplex of America Announces Fate/Stay Night [Unlimited Blade Works] Complete Blu-Ray Box Set

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MAY 13, 2020 Aniplex of America Announces Fate/stay night [Unlimited Blade Works] Complete Blu-ray Box Set ©TYPE-MOON, ufotable, FSNPC Legendary Fate/stay night [Unlimited Blade Works] series gets a complete Blu-ray box set release in July 2020! SANTA MONICA, CA (MAY 13, 2020) – Aniplex of America is excited to confirm the Fate/stay night [Unlimited Blade Works] Complete Blu-ray Box Set is scheduled for release on July 14, 2020. The box set will contain eight discs featuring all 26 uncut episodes from the first and second season of the series, plus the special OVA episode, "sunny day." The must-own set features stunning package illustrations by Takashi Takeuchi (Original Character Design) and comes with an exclusive mini-booklet, along with textless openings and endings as well as a slew of promotional videos, commercials, TV spots, and trailers. Pre-orders for the Fate/stay night [Unlimited Blade Works] Complete Blu-ray Box Set are open now at online retailer RightStuf Anime (https://www.rightstufanime.com/) Fate/stay night [Unlimited Blade Works] premiered in October 2014 and has quickly proven to be an enduring fan favorite series celebrated for the exceptional animation production by ufotable, who successfully produced Fate/Zero and the Garden of sinners. Based on TYPE-MOON’s visual novel Fate/stay night featuring an original story by Kinoko Nasu and original character design by Takashi Takeuchi, the series is directed by Takahiro Miura (Today’s MENU for EMIYA Family) with music by Hideyuki Fukasawa (Fate/Grand Order The Movie Divine Realm of the Round Table: Camelot) and character design by Tomonori Sudo (Fate/stay night [Heaven’s Feel]), Hisayuki Tabata (Fate/stay night [Heaven’s Feel]), and Atsushi Ikariya (Fate/Zero). -

Empty Boundaries – Volume 2

Empty Boundaries: Volume II The Garden of Sinners by Kinoko Nasu (奈須 きのこ) Stories by Kinoko Nasu Novels Empty Boundaries (空の境界) Series Volume I: Panorama, The First Homicide Inquiry, Lingering Pain Volume II: A Hallow, Paradox Spiral Volume III: Records in Oblivion, The Second Homicide Inquiry Decoration Disorder Disconnection Series Junk the Eater HandS Angel Notes Mage’s Night (魔法使いの夜) Ice Flowers (氷の花) Visual Novels Tsukihime (月姫) Series Tsukihime (月姫) Kagetsu Tōya (歌月十夜) Fate/stay night Series Fate/stay night Fate/hollow ataraxia Video games Melty Blood PUBLISHING HISTORY Part 4: A Hallow (伽藍の洞); Part 5: Paradox Spiral (矛盾螺旋); first serialized in the website Takebōki (竹箒, “http://www.remus.dti.ne.jp/~takeucto/”) in 1998. Collected and self-published by the author in hardcover on December 2001. Kōdansha hardcover edition published August 2004. Kōdansha mass market paperback edition published on December 2007. Cover art and internal art by Takashi Takeuchi (武内 崇) Translation by “Cokesakto” This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the prodcut of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales, is entirely coincidental. Empty Boundaries: Volume II Part IV: A Hallow/ page 2 Part V: Paradox Spiral/ page 44 Part IV: A Hallow That which is discordant. That which is hated. That which is intolerable. Accept these things and all others, and never know pain. That which is harmonious. That which is desired. That which is permitted. Reject these things and all others, and know nothing but pain. One affirms, one denies. -

NDK 2019 Program

WELCOME WELCOME TO THE 23RD YEAR OF NAN DESU KAN! Important s we enter our last year at the Notes Sheraton, we are reminded of how Afortunate we are. For the past Please note that our 23 years, we have been working to grow and Cosplay Café is a paid serve the anime community in Colorado and event. Please register surrounding states. We are proud to still be at our Merch room here, and stand for our fandom while still in Plaza Court 2. working to complete our mission statement as There are a handful a registered 501 c(4) Nonprofit Organization. of craft panels that require you to pay a For us, the love of anime and Japanese culture small materials fee. isn’t just a marketing tool or a nifty feature Please pay the amount on our schedule; it’s our purpose for existing indicated in the panel and a mandate of our Nonprofit Charter. We description directly to bring people together to further the knowledge the person running of Japanese Art, animation and culture, and the panel itself! welcome people from all over the region under Take a look at our our roof. We include people of all fandoms, Photography rules ethnicities and identities...and have been for for both cosplayers our whole existence. We choose charities that and photographers! mean something to the community both local Please note that our and nationwide. We actually care, and will Burlesque Show is continue to do so as long as we possibly can. a strict 18+ show, no exceptions! For our theme this year, are declaring 2019 as the Year of the Gamer! We have greatly expanded TABLE our Gaming community over the past few years to over 10,000 square feet of dedicated gaming OF CONTENTS space! We are proud to announce the opening the 4 Rules & Policies Senjo Gamer’s Market next to our ever-popular Gaming Dojo! As always, we are continually 6 Map increasing the quality and growing the number of 7 N. -

️ Program Guide (PDF)

STAFF Convention Chair: Photography Guest Staff Main Events Rosa Halcomb Head: Kristin Roberts Head: Maya King Head: Greg Crouse Vice Chair: Shawn Bailey Staff: Amber Feldman, Marcy Staff: Keith Berans, Trevor Press LaRue, Steven Godbey, Kyle Breault, Bob Malmin, Kelsey-jo Head: Tanya Perez Business Brooks, Mario Orozco, Kristine Thibodeau, Jessica Williams, Staff: Michelle Harvey, Ryan Director: Katie Lynn Barnum Nia Gray Harvey, Luke Marsden Registration Tabletop Gaming Head: James Wigton Public Relations Programming Director: Greg Hines Head: Jaqi Judson Staff: Sam Wilson, Joseph Head: Gareth Lypka Staff: Victoria Strong, Staff: Bryce Andersen, Patrick Menke, Sean Breen, Teesha Staff: Cara Logan Anthony Bagley, Marlon Brownson, Sinead Cooper, Prichard, Zachary Patterson Operations Bennett, Meghan Bethards, Lanning Henriques, Leah Vendors’ Hall Director: James Kirkham Rebecca Anne Chambers, Stevens, Julian Anthony, Kaylyn Head: Emily Kringle Hatfield Convention Operations Austin Cunningham, Laurel Staff: Zoraida Hayes, Anthony Head: Joel Berger Fiddler, Kaeden Grigsby, Chris Video Gaming Van Risseghem, Justin Rose, Staff: Jordan Rogell, John Mauricio, Kerry McCullough, Head: Mark Kraska, Kurtis Monterey Pulliam, Kelsea Christison, Rebecaa Friend, Jose Angel Torres, Shola York, Heithoff, Kohler Richard W Donnelly Jr., Jessica Danielle Wayne, Marshall Staff: Kyle Le, Keith Adamson, Artists’ Alley Knoedler, Kyle Knoedler, Teresa Jeremy Witherspoon, Linh Vu, Kelly Bohan, Meredith Head: Jamie Judson Carnes, Adam Franklin Lee, Cody Cooper, Zane Wewerka, Dickerson, Daniel Eason, Matt José Torres, Justin Walker Katia Bermejo Harper, Aaron King, Harris Merchandising Kalat, Meg Kraska, Matt Head: Trevor Hodgson Convention Response Team Adult Programming Head: Warumuno Rowles, Gary Schmidt, Garret Staff: Ryan Hodgson Head: Forrest Fredell Stewart, Chase Hainey, Sean Staff: DJ Harshman, Allison AMVs Fleming, Christopher Bennett Communications Rosenthal, Mariona Gates, Head: Shawn Bailey Director: A. -

Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Transnational Consumption of Manga, Anime, and Media-Mixes

Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Transnational Consumption of Manga, Anime, and Media-Mixes Edited by Manuel Hernández-Pérez Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Arts www.mdpi.com/journal/arts Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Transnational Consumption of Manga, Anime, and Media-Mixes Special Issue Editor Manuel Hern´andez-P´erez MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Manuel Hernandez-P´ erez´ University of Hull UK Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Arts (ISSN 2076-0752) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/arts/special issues/japanese media consumption). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-008-4 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-009-1 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Manuel Hernandez-P´ erez.´ c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. -

Sakura-Con 2011

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2011 FRIDAY-SATURDAY, April 22nd-23rd (2 of 4) FRIDAY-SATURDAY, April 22nd-23rd (3 of 4) FRIDAY-SATURDAY, April 22nd-23rd (4 of 4) Convention Events Schedule, April 20 revision Panels 3 Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Console Gaming Arcade Gaming Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Karaoke Youth Matsuri Collectible Card Gaming Roleplaying Gaming 606 607 611-612 Time 613-614 3AB 205 Time Time 309 4C-3,4 4C Lobby Time 615-617 604 306 618-620 Theater: 6A 2AB 310 Time 307-308 305 Time Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am FRIDAY-SATURDAY, April 22nd-23rd (1 of 4) 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 (8:15) (8:15) (8:15) (8:15) Gintama 1-9 Magical Shopping Arcade Rurouni Kenshin 1-4 Kenichi: The Mightiest Time 4A 4B Time 6E 6C 608-609 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-PG V, sub) Abenobashi 1-4 (SC-PG V, sub) Disciple 1-7 9:00am Closed Closed 9:00am Closed Closed Closed 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am (SC-PG SLD, dub) (SC-PG VSD, dub) AMV Showcase Open Mic 9:00am 9:00am 9:30am 9:30am 9:30am 9:30am 9:30am 9:30am (SC-PG) 9:30am 9:30am 10:00am Opening Ceremonies 10:00am Poi Spinning 10:00am 10:00am 10:00am Open Gaming Open Gaming 10:00am Kannagi: