Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Issue 17 March 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal ‘UNPEELING THE LAYERS WITHIN YOURSELF ’ Editorial Consultant Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry Samik Bandyopadhyay 22 Project Co-ordinator A GATKA WORKSHOP : A PARTICIPANT ’S REPORT Paramita Banerjee Ramanjit Kaur Design 32 Naveen Kishore THE MYTH BEYOND REALITY : THE THEATRE OF NEELAM MAN SINGH CHOWDHRY Smita Nirula 34 THE NAQQALS : A NOTE 36 ‘THE PERFORMING ARTIST BELONGED TO THE COMMUNITY RATHER THAN THE RELIGION ’ Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry on the Naqqals 45 ‘YOU HAVE TO CHANGE WITH THE CHANGING WORLD ’ The Naqqals of Punjab 58 REVIVING BHADRAK ’S MOGAL TAMSA Sachidananda and Sanatan Mohanty 63 AALKAAP : A POPULAR RURAL PERFORMANCE FORM Arup Biswas Acknowledgements We thank all contributors and interviewees for their photographs. 71 Where not otherwise credited, A DIALOGUE WITH ENGLAND photographs of Neelam Man Singh An interview with Jatinder Verma Chowdhry, The Company and the Naqqals are by Naveen Kishore. 81 THE CHALLENGE OF BINGLISH : ANALYSING Published by Naveen Kishore for MULTICULTURAL PRODUCTIONS The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Jatinder Verma 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 86 MEETING GHOSTS IN ORISSA DOWN GOAN ROADS Printed at Vinayaka Naik Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Kristen Dawn Rudisill certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT Committee: ______________________________ Kathryn Hansen, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Martha Selby, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Kamran Ali ______________________________ Charlotte Canning BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT by Kristen Dawn Rudisill, B.A.; A.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 For Justin and Elijah who taught me the meaning of apu, pācam, kātal, and tuai ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I came to this project through one of the intellectual and personal journeys that we all take, and the number of people who have encouraged and influenced me make it too difficult to name them all. Here I will acknowledge just a few of those who helped make this dissertation what it is, though of course I take full credit for all of its failings. I first got interested in India as a religion major at Bryn Mawr College (and Haverford) and classes I took with two wonderful men who ended up advising my undergraduate thesis on the epic Ramayana: Michael Sells and Steven Hopkins. Dr. Sells introduced me to Wendy Doniger’s work, and like so many others, I went to the University of Chicago Divinity School to study with her, and her warmth compensated for the Chicago cold. -

The Mahatma As Proof: the Nationalist Origins of The

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Mahatma Misunderstood: the politics and forms of South Asian literary nationalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/77d6z8xw Author Shingavi, Snehal Ashok Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Mahatma Misunderstood: the politics and forms of South Asian literary nationalism by Snehal Ashok Shingavi B.A. (Trinity University) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Prof. Abdul JanMohamed, chair Prof. Gautam Premnath Prof. Vasudha Dalmia Fall 2009 For my parents and my brother i Table of contents Chapter Page Acknowledgments iii Introduction: Misunderstanding the Mahatma: the politics and forms of South Asian literary nationalism 1 Chapter 1: The Mahatma as Proof: the nationalist origins of the historiography of Indian writing in English 22 Chapter 2: “The Mahatma didn’t say so, but …”: Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable and the sympathies of middle-class 53 nationalists Chapter 3: “The Mahatma may be all wrong about politics, but …”: Raja Rao’s Kanthapura and the religious imagination of the Indian, secular, nationalist middle class 106 Chapter 4: The Missing Mahatma: Ahmed Ali’s Twilight in Delhi and the genres and politics of Muslim anticolonialism 210 Conclusion: Nationalism and Internationalism 306 Bibliography 313 ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, this dissertation would have been impossible without the support of my parents, Ashok and Ujwal, and my brother, Preetam, who had the patience to suffer through an unnecessarily long detour in my life. -

Volume 1 on Stage/ Off Stage

lives of the women Volume 1 On Stage/ Off Stage Edited by Jerry Pinto Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media Supported by the Laura and Luigi Dallapiccola Foundation Published by the Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media, Sophia Shree B K Somani Memorial Polytechnic, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Mumbai 400 026 All rights reserved Designed by Rohan Gupta be.net/rohangupta Printed by Aniruddh Arts, Mumbai Contents Preface i Acknowledgments iii Shanta Gokhale 1 Nadira Babbar 39 Jhelum Paranjape 67 Dolly Thakore 91 Preface We’ve heard it said that a woman’s work is never done. What they do not say is that women’s lives are also largely unrecorded. Women, and the work they do, slip through memory’s net leaving large gaps in our collective consciousness about challenges faced and mastered, discoveries made and celebrated, collaborations forged and valued. Combating this pervasive amnesia is not an easy task. This book is a beginning in another direction, an attempt to try and construct the professional lives of four of Mumbai’s women (where the discussion has ventured into the personal lives of these women, it has only been in relation to the professional or to their public images). And who better to attempt this construction than young people on the verge of building their own professional lives? In learning about the lives of inspiring professionals, we hoped our students would learn about navigating a world they were about to enter and also perhaps have an opportunity to reflect a little and learn about themselves. So four groups of students of the post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media, SCMSophia’s class of 2014 set out to choose the women whose lives they wanted to follow and then went out to create stereoscopic views of them. -

Sombhu Mitra 1914-1997

In Memory ±ombhu Mitra 1914²1997 Spoken-word 45 rpm gramophone records were once a prized possession in many Bengali middle- class households of Calcutta that dabbled in high cul- ture. There were a handful of elocutionists who released albums of poetry quite regularly. Among the many albums in our record collection was one that featured baritone artists reciting some of the best specimens of Bengali poetry. But there was one voice among them whose timbre was of a different sort. To my adolescent ears it was not particularly pleasurable to hear, but singular in its tenored nu- ances, in its intensity of expression and clarity of pronunciation. It was ±ombhu Mitra’s rendition of a poem by the Bengali pantheist poet, J }ban nda D s. There was something in Mitra’s vocalization that stirred my adolescent spirit. I had never known me- chanically reproduced spoken words to engender such intense emotions. My elders told me I was un- fortunate to have missed seeing Mitra in action onstage. He had retired just a few years before I was of age to see and make sense of a play. Then, a few years later, there was news that Mitra was coming out of retirement to play the title role in Bertolt Brecht’s Life of Galileo under the direction of the East German director Fritz Benevitz. I stood in line for a whole night to get tickets. The experience of seeing Mitra live was indescrib- able. This was my first Brecht play and was it a grand introduction! Mitra’s depiction of Galileo from late youth to senility was a display of such amazing dexterity in vocal as well as physical acting, such richness of characterization, replete with details and subtleties, that I simply had to see the play again the next night. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Indian Theatre Autobiographies Kindle

STAGES OF LIFE : INDIAN THEATRE AUTOBIOGRAPHIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kathryn Hansen | 392 pages | 01 Dec 2013 | Anthem Press | 9781783080687 | English | London, United Kingdom Stages of Life : Indian Theatre Autobiographies PDF Book All you need to know about India's 2 Covid vaccines. Celebratory firing: yr-old killed at Lohri event in Talwandi Sabo village. Khemta dances may be performed on any occasion, and, at one time, were popular at weddings and pujas. For a full translation via Bengali see The Wonders of Vilayet , tr. First, he used Grose's phrases for descriptions of topics which Dean Mahomet did not know, most notably the cities of Surat and Bombay, and also classical quotations from Seneca and Martial. He never explained the reasons for this next immigration and, indeed, later omitted his years in Ireland from his autobiographical writings altogether. London: Anthem Press. Samples of 3 dead birds found negative in Ludhiana 9 hours ago. Other Formats Available: Hardback. India's artistic identity is deeply routed within its social, economical, cultural, and religious views. For privacy concerns, please view our Privacy Policy. The above passage can be taken as example of the Vaishnav value system within which Girish Ghosh would always configure the identity and work of an actor. Main article: Sanskrit drama. This imagination serves as a source of creative inspiration in later life for artists, writers, scientists, and anyone else who finds their days and nights enriched for having nurtured a deep inner life. CBSE schools begin offline classes 9 hours ago. In Baumer and Brandon , xvii—xx. Thousands of tractors to leave for Delhi on Jan 20 9 hours ago. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

AXC Instructions / ૂચના

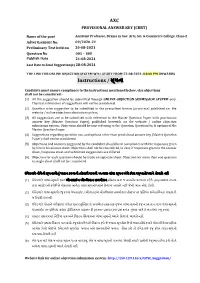

AXC PROVISIONAL ANSWER KEY (CBRT) Name of the post Assistant Professor, Drama in Gov. Arts, Sci. & Commerce College, Class-2 Advertisement No. 69/2020-21 Preliminary Test held on 20-08-2021 Question No 001 – 300 Publish Date 21-08-2021 Last Date to Send Suggestion(s) 28-08-2021 THE LINK FOR ONLINE OBJECTION SYSTEM WILL START FROM 22-08-2021; 04:00 PM ONWARDS Instructions / ચનાૂ Candidate must ensure compliance to the instructions mentioned below, else objections shall not be considered: - (1) All the suggestion should be submitted through ONLINE OBJECTION SUBMISSION SYSTEM only. Physical submission of suggestions will not be considered. (2) Question wise suggestion to be submitted in the prescribed format (proforma) published on the website / online objection submission system. (3) All suggestions are to be submitted with reference to the Master Question Paper with provisional answer key (Master Question Paper), published herewith on the website / online objection submission system. Objections should be sent referring to the Question, Question No. & options of the Master Question Paper. (4) Suggestions regarding question nos. and options other than provisional answer key (Master Question Paper) shall not be considered. (5) Objections and answers suggested by the candidate should be in compliance with the responses given by him in his answer sheet. Objections shall not be considered, in case, if responses given in the answer sheet /response sheet and submitted suggestions are differed. (6) Objection for each question should be made on separate sheet. Objection for more than one question in single sheet shall not be considered. ઉમેદવાર નીચેની ૂચનાઓું પાલન કરવાની તકદાર રાખવી, અયથા વાંધા- ૂચન ગે કરલ રૂઆતો યાને લેવાશે નહ (1) ઉમેદવાર વાંધાં- ૂચનો ફત ઓનલાઈન ઓશન સબમીશન સીટમ ારા જ સબમીટ કરવાના રહશે. -

Criterion an International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165

The Criterion www.the-criterion.com An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Revitalizing the Tradition: Mahesh Dattani’s Contribution to Indian English Drama Farah Deeba Shafiq M.Phil Scholar Department of English University of Kashmir Indian drama has had a rich and ancient tradition: the natyashastra being the oldest of the texts on the theory of drama. The dramatic form in India has worked through different traditions-the epic, the folk, the mythical, the realistic etc. The experience of colonization, however, may be responsible for the discontinuation of an indigenous native Indian dramatic form.During the immediate years following independence, dramatists like Mohan Rakesh, Badal Sircar, Girish Karnad, Vijay Tendulkar, Dharamvir Bharati et al laid the foundations of an autonomous “Indian” aesthetic-a body of plays that helped shape a new “National” dramatic tradition. It goes to their credit to inaugurate an Indian dramatic tradition that interrogated the socio-political complexities of the nascent Indian nation. However, it’s pertinent to point out that these playwrights often wrote in their own regional languages like Marathi, Kannada, Bengali and Hindi and only later translated their plays into English. Indian English drama per se finds its first practitioners in Shri Aurobindo, Harindarnath Chattopadhyaya, and A.S.P Ayyar. In the post- independence era, Asif Curriumbhoy (b.1928) is a pioneer of Indian English drama with almost thirty plays in his repertoire. However, owing to the spectacular success of the Indian English novel, Drama in English remained a minor genre and did not find its true voice until the arrival of Mahesh Dattani. -

Hindu Patrika

Board of Trustees C HINDU PATRIKAC Term Name Published 2009-2011 Vishal Adma Chairman Bimonthly 2010-2012 Deb Bhaduri Vice Chair DECEMBER/JANUARY 2012 Vol 17/2011 2009-2011 Sanjeev Goyal 2009-2011 Mahendra Sheth 2010-2012 Sadhana Bisarya 2010-2012 Sanjay Mishra 2009-2011 Vishal Adma 2010-2012 Manu Rattan 2011-2013 Mohan Gupta 2011-2013 Priti Mohan 2011-2013 Govind Patel 2011-2013 Mana Pattanayak 2011-2013 Eashwer Reddy 2011 Neelam Kumar 2011 Sridhar Harohalli Vision of HTCC To promote Hinduism’s spiritual and cultural legacy of inspiration and optimism for the larger Kansas City community. Mission of HTCC • Create an environment of worship that enables people to say “yes” to the love of God. • Cultivate a community that nurtures spiritual growth. • Commission every devotee to serve the creation through their unique talents and gifts. • Coach our youth with the spiritual and cultural richness and the diversity they are endowed with • Communicate Hinduism – A way of life to everyone we can and promote inter-faith activities with equal veneration Hindu Temple & Cultural Center of Kansas Hindu Temple Wishes a Very Happy New Year to all the City Members A NON-PROFIT TEMPLE HOURS Day Time Aarti ORGANIZATION Mon - Fri 10:00am-12:00pm 11:00am Please remember to renew your annual membership which runs from January to 6330 Lackman Road Mon - Fri 5:00pm-8:00pm 7:30pm Shawnee, KS 66217-9739 Sat & Sun 9:00am-8:00pm 12:00pm December. Sat & Sun 7:30pm http://www.htccofkc.org Your Current membership status is printed on the mailing label.