Sombhu Mitra 1914-1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Issue 17 March 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal ‘UNPEELING THE LAYERS WITHIN YOURSELF ’ Editorial Consultant Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry Samik Bandyopadhyay 22 Project Co-ordinator A GATKA WORKSHOP : A PARTICIPANT ’S REPORT Paramita Banerjee Ramanjit Kaur Design 32 Naveen Kishore THE MYTH BEYOND REALITY : THE THEATRE OF NEELAM MAN SINGH CHOWDHRY Smita Nirula 34 THE NAQQALS : A NOTE 36 ‘THE PERFORMING ARTIST BELONGED TO THE COMMUNITY RATHER THAN THE RELIGION ’ Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry on the Naqqals 45 ‘YOU HAVE TO CHANGE WITH THE CHANGING WORLD ’ The Naqqals of Punjab 58 REVIVING BHADRAK ’S MOGAL TAMSA Sachidananda and Sanatan Mohanty 63 AALKAAP : A POPULAR RURAL PERFORMANCE FORM Arup Biswas Acknowledgements We thank all contributors and interviewees for their photographs. 71 Where not otherwise credited, A DIALOGUE WITH ENGLAND photographs of Neelam Man Singh An interview with Jatinder Verma Chowdhry, The Company and the Naqqals are by Naveen Kishore. 81 THE CHALLENGE OF BINGLISH : ANALYSING Published by Naveen Kishore for MULTICULTURAL PRODUCTIONS The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Jatinder Verma 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 86 MEETING GHOSTS IN ORISSA DOWN GOAN ROADS Printed at Vinayaka Naik Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

Satabarshe Sombhu Mitra

Satabarshe Sombhu Mitra UGC Sponsored National Seminar on the Life and Work of Sombhu Mitra Organised by The Bengali and the English Departments of Chandraketugarh Sahidullah Smriti Mahavidyalaya In Collaboration With The Bengali Department of Amdanga Jugalkishore Mahavidyalaya From 22-8-2015 to 23-8-2015 At ‘Uttaran’, B.D.O Office, Deganga Block Debalaya (Berachampa) 743424 Call for Paper It is indeed difficult to overstate the influence of Sombhu Mitra on both the modern Bengali group theatre and the commercial theatres alike. If Nabannna, which came out in 1948 broke new grounds in many ways, Char Adhyay {1951) followed by Raktakarabi (1954), Bisarjan (1961) and Raja (1964) showed the way in which a Tagore play, hitherto widely denounced as unstageable because of its abstractions, can be performed with success on stage without making any substantial departure from the source. While through Tagore’s plays, he was trying to find an expression of the complete man in all contexts of history, Mitra’s Dashachakra (1952) and Putul Khela (1958), adaptations of Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People and Doll’s House, being specimens of the earliest such adaptations for the modern stage, clearly contributed among other playwrights to resist any tendency of cultural insularity of the Bengali stage, though suiting the themes for the dominantly middle class Bengali audience. His translation of Sophocles for the first time for the Bengali stage created new interest in classical drama and set the stage for many such future adaptations. Mitra was always aware of the potentialities of the indigenous forms of drama and Chand Boniker Pala (1978), which was written at a later phase of his life and was meant more for audio presentation than for the stage, takes up a well known story from a Mangalkavya and treats it with a subliminal intertextual link with the Orpheus theme to lend it with themes and motifs at once contemporaneous and eternal for all ages and all times. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Download (5.57

c m y k c m y k Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers of India: Regd. No. 14377/57 CONTRIBUTORS Aziz Quraishi Diwan Singh Bajeli Dr. M. Sayeed Alam Feisal Alkazi Geeta Nandakumar Rana Siddiqui Zaman Salman Khurshid Suresh K Goel Suresh Kohli Tom Alter Indian Council for Cultural Relations Phone: 91-11-23379309, 23379310, 23379314, 23379930 Fax: 91-11-23378639, 23378647, 23370732, 23378783, 23378830 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.iccrindia.net c m y k c m y k c m y k c m y k Indian Council for Cultural Relations The Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) was founded on 9th April 1950 by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the first Education Minister of independent India. The objectives of the Council are to participate in the formulation and implementation of policies and programmes relating to India’s external cultural relations; to foster and strengthen cultural relations and mutual understanding between India and other countries; to promote cultural exchanges with other countries and people; to establish and develop relations with national and international organizations in the field of culture; and to take such measures as may be required to further these objectives. The ICCR is about a communion of cultures, a creative dialogue with other nations. To facilitate this interaction with world cultures, the Council strives to articulate and demonstrate the diversity and richness of the cultures of India, both in and with other countries of the world. The Council prides itself on being a pre-eminent institution engaged in cultural diplomacy and the sponsor of intellectual exchanges between India and partner countries. -

Social Science TABLE of CONTENTS

2015 Social Science TABLE OF CONTENTS Academic Tools 79 Labour Economics 71 Agrarian Studies & Agriculture 60 Law & Justice 53 Communication & Media Studies 74-78 Literature 13-14 Counselling & Psychotherapy 84 7LHJL *VUÅPJ[:[\KPLZ 44-48 Criminology 49 Philosophy 24 Cultural Studies 9-13 Policy Studies 43 Dalit Sociology 8 Politics & International Relations 31-42 Development Communication 78 Psychology 80-84 Development Studies 69-70 Research Methods 94-95 Economic & Development Studies 61-69 SAGE Classics 22-23 Education 89-92 SAGE Impact 72-74 Environment Studies 58-59 SAGE Law 51-53 Family Studies 88 SAGE Studies in India’s North East 54-55 Film & Theatre Studies 15-18 Social Work 92-93 Gender Studies 19-21 Sociology & Social Theory 1-7 Governance 50 Special Education 88 Health & Nursing 85-87 Sport Studies 71 History 25-30 Urban Studies 56-57 Information Security Management 71 Water Management 59 Journalism 79 Index 96-100 SOCIOLOGY & SOCIAL THEORY HINDUISM IN INDIA A MOVING FAITH Modern and Contemporary Movements Mega Churches Go South Edited by Will Sweetman and Aditya Malik Edited by Jonathan D James Edith Cowan University, Perth Hinduism in India is a major contribution towards ongoing debates on the nature and history of the religion In A Moving Faith by Dr Jonathan James, we see for in India. Taking into account the global impact and the first time in a single coherent volume, not only that influence of Hindu movements, gathering momentum global Christianity in the mega church is on the rise, even outside of India, the emphasis is on Hinduism but in a concrete way, we are able to observe in detail as it arose and developed in sub-continent itself – an what this looks like across a wide variety of locations, approach which facilitates greater attention to detail cultures, and habitus. -

Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016

All Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016 Yea Sub Artist Name Field Category r Category Prabhakar Karekar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Padma Talwalkar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Koushik Aithal - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Yuva Puraskar 6 Yashasvi 201 Sirpotkar - Yuva Music Hindustani Vocal 6 Puraskar Arvind Mulgaonkar - 201 Music Hindustani Tabla Akademi 6 Awardee Yashwant 201 Vaishnav - Yuva Music Hindustani Tabla 6 Puraskar Arvind Parikh - 201 Music Hindustani Sitar Akademi Fellow 6 Abir hussain - 201 Music Hindustani Sarod Yuva Puraskar 6 Kala Ramnath - 201 Akademi Music Hindustani Violin 6 Awardee R. Vedavalli - 201 Music Carnatic Vocal Akademi Fellow 6 K. Omanakutty - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Neela Ramgopal - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Srikrishna Mohan & Ram Mohan 201 (Joint Award) Music Carnatic Vocal 6 (Trichur Brothers) - Yuva Puraskar Ashwin Anand - 201 Music Carnatic Veena Yuva Puraskar 6 Mysore M Manjunath - 201 Music Carnatic Violin Akademi 6 Awardee J. Vaidyanathan - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee Sai Giridhar - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee B Shree Sundar 201 Kumar - Yuva Music Carnatic Kanjeera 6 Puraskar Ningthoujam Nata Shyamchand 201 Other Major Music Sankirtana Singh - Akademi 6 Traditions of Music of Manipur Awardee Ahmed Hussain & Mohd. Hussain (Joint Award) 201 Other Major Sugam (Hussain Music 6 Traditions of Music Sangeet Brothers) - Akademi Awardee Ratnamala Prakash - 201 Other Major Sugam Music Akademi -

Murdering Journalists

A JOURNAL OF THE PRESS INSTITUTE OF INDIA ISSN 0042-5303 October-December 2017 Volume 9 Issue 4 Rs 60 Murdering journalists: CONTENTS • When the media ignored its own principles / Bharat the much larger attack Dogra • GST – a good and simple tax? / Shreejay Sinha When writer-activist Gauri Lankesh was shot dead in Bengaluru • Do Indian cinema and on September 5, it was not just one journalist or one fearless television mimic life, or vice- female activist who was murdered. It was a manifestation of versa? / Pushpa Achanta • Dhananjoy and the death something far, far larger – the maiming of a big chunk of the sentence / Shoma A. lives and futures of 1.2-odd billion Indians, no less, a big chunk Chatterji of the fundamental rights of each citizen, and a big chunk of the • Can’t we make room for Constitution that we gave to ourselves with such pride 70 years people with disabilities? / ago, says Sakuntala Narasimhan Aditi Panda • Fostering change-makers, making the world a ut aside the political imputations for a moment. As of this writing (end- better place / Sakuntala September*), the case is still being investigated, the guilty are yet to be Narasimhan Pidentified. Just collate the facts on a wider canvas, and what you have, as • Creativity: the missing the larger picture, is a collection of events that spell murder of a basic concept ingredient in Chinese of democracy, something more than an attack on an individual, a woman, an thinking? / Asma Masood activist, or journalist. • Another scribe falls victim to If I cannot eat what my family -

Kavalam Narayana Panikkar (1928-2016): a Tribute

Bharatiya Pragna: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Indian Studies (E-ISSN 2456-1347) Ed. by Dr. P. Mallikarjuna Rao Vol. 1, No. 2, 2016. URL of the Issue: http://www.indianstudies.net/v1n2 Available at http://www.indianstudies.net/V1/n2/01_KN-Panikkar.pdf © AesthetixMS Kavalam Narayana Panikkar (1928-2016): A Tribute Rajesh P1 University of Hyderabad, India Kavalam, a small village alongside the backwaters of Kerala is today known after a thespian par excellence. Kavalam Narayana Panikkar who carried along with him not just the name of his village, but the rhythm of folk, while in search of the ‘roots’ of Indian art forms. With a profound knowledge of the folk arts of Kerala such as Theyyam, Padayani, Koodiyattam and Kakkarishi Natakam1, he became advocate of the “Theatre of Roots” along with Habib Tanvir, Vijay Tendulkar, Ratan Tiyam and Girish Karnad. His contributions to the revival of Tanathu (indigenous) art forms remain unsurpassed. K. N. Panikkar, popularly known as Kavalam was born into an affluent family with rich cultural heritage of Kuttanad; he worked relentlessly for the revival of native theatre by incorporating classical, folk and western theaters, though not without criticism. Even as a theatre doyen, he was involved in kalari2 till his last days, meditating over his latest drama Rithambara.3 He remained a multitalented artist and made significant contributions as a playwright, director, lyricist and singer. K. N. Panikkar would have remained a lawyer had his disposition not inclined to the culture abundance around him. His six years practice after obtaining a law degree was replaced by an artistic career spanning over half a century, transcending the discipline with an extensive repertoire of folk art. -

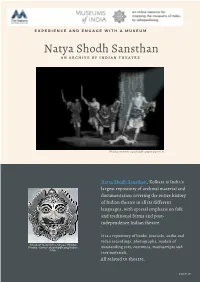

Natya Shodh Sansthan a N a R C H I V E O F I N D I a N T H E a T R E

E X P E R I E N C E A N D E N G A G E W I T H A M U S E U M Natya Shodh Sansthan A N A R C H I V E O F I N D I A N T H E A T R E Photo: www.natyashodh.org/index.htm Natya Shodh Sansthan, Kolkata is India's largest repository of archival material and documentation covering the entire history of Indian theatre in all its different languages, with special emphasis on folk and traditional forms and post- independence Indian theatre It is a repository of books, journals, audio and video recordings, photographs, models of Mask of Narsimha, Orissa, Photo: Photo: www.natyashodh.org/index. outstanding sets, costumes, manuscripts and htm rare materials. All related to theatre. PAGE 01 N a t y a S h o d h S a n s t h a n | E xperience & Engage with a Museum PAGE 02 P A G E 0 2 Natya Shodh Sansthan began its journey in July, 1981 as a theatre archive from 11, Pretoria Street, Kolkata, as a unit of Upchar Trust. The modest holding of a few journals, leaflets and diaries grew and the Sansthan built up its collection of priceless materials. Seminars, discussions and talks were regularly organized to record various aspects of histrionics on a pan-Indian level. With the new building established in 2019 (left hand side images), the Museum found its present address at EE 8, Sector 2, Salt Lake (Bidhan Nagar), Kolkata. -

Nobel Prize - 2015

Nobel prize - 2015 ★ Physics - Takaaki Kajita, Arthur B. Mcdonald ★Chemistry - Tomas Lindahl, Paul L. Modrich, Aziz Sanskar ★Physiology or Medicine - William C. Campbell, Satoshi Omura, Tu Youyou ★Literature - Svetlana Alexievich (Belarus) ★Peace - Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet ★Economics - Angus Deaton Nobel prize - 2016 ★Physics - David J. Thouless, F. Duncan M. Haldane, J. Michael Kosterlitz ★Chemistry - Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J.Fraser Stoddart, Bernard L. Feringa ★Physiology or Medicine - Yoshinori Ohsumi ★Literature - Bob Dylan ★Peace - Juan Manuel Santos ★Economics - Oliver Hart, Bengt Holmstrom Nobel prize - History Year Honourable Subject Origin 1902 Ronald Ross Medicine Foreign citizen born in India 1907 Rudyard Kipling Literature Foreign citizen born in India 1913 Rabindranath Literature Citizen of India Tagore 1930 C.V. Raman Physics Citizen of India 1968 Har Gobind Medicine Foreign Citizen of Indian Khorana Origin 1979 Mother Teresa Peace Acquired Indian Citizenship 1983 Subrahmanyan Physics Indian-born American Chandrasekhar citizen 1998 Amartya Sen Economi Citizen of India c Sciences 2009 Venkatraman Chemistr Indian born American Ramakrishna y Citizen Booker Prize Year Author Title 2002 Yann Martel Life of Pi 2003 DBC Pierre Vernon God Little 2006 Kiran Desai The Inheritance of Loss 2008 Aravind Adiga The White Tiger 2009 Hilary Mantel Wolf hall 2010 Howard Jacobson The Finkler Question 2011 Julian Barnes The Sense of an Ending 2012 Hilary Mantel Bring Up the Bodies 2013 Eleanor Catton The Luminaries 2014 Richard Flanagan The Narrow Road to the Deep North 2015 Marlon James A Brief History of Seven Killings 2016 Han Kang, Deborah Smith The Vegetarian Booker Prize - Facts ★In 1993 on 25th anniversary it was decided to choose a Booker of Bookers Prize and the decision was done by a panel of three judges. -

Bal Gandharva’

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Dhyaneshwar Nadkarni On ‘Bal Gandharva’ FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY Recorded on 16th. April, 1988 Natya Bhavan EE 8, Sector 2, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700091/ Call 033 23217667 visit us at www.natyashodh.org / https://sites.google.com/view/nssheritagelibrary/home Samik Bandyopadhyay 16th April 1988, we are recording the talk by Dhyaneshwar Nadkarni at Natya Shodh Sansthan; he is speaking on Bal Gandharva. Ladies and gentlemen, we are happy to have with us Dhyaneshwar Nadkarni this evening and for tomorrow morning also. Now those who have been reading our news bulletin, the ‘Rangvarta’, will be aware of the fact that in quite a number of issues we have been raising the question of theatre criticism and its limitations, its problems in India. This has been a very serious problem for Indian theatre. Such a lot of wonderful work is done in Indian theatre, but so little of that is properly evaluated, recorded for later generations. Whenever we try to understand a theatre of the past we always face this problem because the records, the critical records are so inadequate. There is fairly reporting of events but very little beyond that. So we have been very conscious of this through from the archive we can’t change the nature and base of criticism. We have been trying to provide criticism with enough material to feed on to build on. That is been part of our major endeavor. This is the context in which we have invited Dhyaneshwar Nadkarni to speak to us because he has been a very exceptional kind of critic in the field of theatre criticism because he has been simultaneously studying, observing and very solidly criticizing three parallel areas of the arts – theatre, cinema and fine arts. -

Report 1967-68

REPORT 1967-68 Acc. N o........................... ............. Date ......................................... Asian Institute of Bdurynntl Planning and Admin i«ii»n Library ■T'J !»■«.* \ ( I .i’A DC D 13532 MINISTRY OF EDUCATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 1968 Publication No. 822 / : ' n • M • • v' - 1 ng aric. Aw. -u CONTENTS Llbrary C hapters P a c i s I. Introductory ........ 1 II. School Education ....... 4 III. National Council of Educational Research and Training 13 IV. Education in the Union Territories .... 23 V. Eigher Education ....... 33 VI. lechnical Education ...... 49 VII. S:ientific Surveys and Development .... 56 VIII. Council of Scientific and Industrial Research . 70 IX. S : h o l a r s h i p s ........................................................... 76 X. S>cial Education, Reading Materials and Libraries . 89 XI. Piysica! Education, Games, Sports and Youth Welfare . 97 XII. Eevelopment of Hindi, Sanskrit and Modern Indian Languages ........ 108 XIII. Lterature and Information ..... 124 X IV . F n e Arts .................................................................................. 131 XV. Vuseums, Archaeology and Archives . 138 XVI. Ciltural Relations with Foreign Countries . 153 XVII. Ctoperation with the United Nations Educational, Scienti- ic and Cultural Organisations ..... 162 A n n e w u s I. Atached and Subordinate Offices and Autonomous Organisations of the Ministry of Education . 181 II. Uiiversities including Institutions Deemed to be Universi- i e s .............................................................................................. 186 ID. Publications Brought out by the Ministry of Education and is A g e n c i e s ...................................................................... ........... 190 IY. tOndriya Vidyalayas (Central Schools) . 196 C h a r ' s I. Vministrative Chart of the Ministry of Education II. Pngress of Primary Education III. Pngress of Middle School Education IV.