Hostile Intent and Counter-Terrorism Human Factors Theory and Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—And Possible Policy Responses Kumar Ramakrishna S

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 6 3-20-2017 The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—and Possible Policy Responses Kumar Ramakrishna S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the International Relations Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Public Policy Commons, and the Terrorism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ramakrishna, Kumar (2017) "The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—and Possible Policy Responses," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 29 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol29/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New England Journal of Public Policy The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—and Possible Policy Responses Kumar Ramakrishna S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore This article examines the radicalization of young Southeast Asians into the violent extremism that characterizes the notorious Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). After situating ISIS within its wider and older Al Qaeda Islamist ideological milieu, the article sketches out the historical landscape of violent Islamist extremism in Southeast Asia. There it focuses on the Al Qaeda-affiliated, Indonesian-based but transnational Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) network, revealing how the emergence of ISIS has impacted JI’s evolutionary trajectory. -

The UK's Experience in Counter-Radicalization

APRIL 2008 . VOL 1 . ISSUE 5 The UK’s Experience in published in October 2005, denied having “neo-con” links and supporting that Salafist ideologies played any role government anti-terrorism policies.4 Counter-Radicalization in the July 7 bombings and blamed Rafiq admitted that he was unprepared British foreign policy, the Israeli- for the hostility—or effectiveness—of By James Brandon Palestinian conflict and “Islamophobia” these Islamist attacks: for the attacks.1 They recommended in late april, a new British Muslim that the government tackle Islamic The Islamists are highly-organized, group called the Quilliam Foundation, extremism by altering foreign policy motivated and well-funded. The th named after Abdullah Quilliam, a 19 and increasing the teaching of Islam in relationships they’ve made with century British convert to Islam, will be schools. Haras Rafiq, a Sufi member of people in government over the last launched with the specific aim of tackling the consultations, said of the meetings: 20 years are very strong. Anyone “Islamic extremism” in the United “It was as if they had decided what their who wants to go into this space Kingdom. Being composed entirely findings were before they had begun; needs to be thick-skinned; you of former members of Hizb al-Tahrir people were just going through the have to realize that people will lie (HT, often spelled Hizb ut-Tahrir), the motions.”2 about you; they will do anything global group that wants to re-create to discredit you. Above all, the the caliphate and which has acted as Sufi Muslim Council attacks are personal—that’s the a “conveyor belt” for several British As a direct result of witnessing the way these guys like it. -

Mateen in Orlando That Killed 49 Reminds Us That Despite All These FBI Investigations, Sometimes America’S Homegrown Terrorists Will Still Slip Through the Net

The Future of Counterterrorism: Addressing the Evolving Threat to Domestic Security. House Committee on Homeland Security Committee, Counterterrorism and Intelligence Subcommittee February 28, 2017 Peter Bergen , Vice President, Director of International Security and Fellows Programs, New America; Professor of Practice, Arizona State University; CNN National Security Analyst. This testimony is organized into 8 sections 1. What is the terrorism threat to the U.S.? 2. What is the terrorism threat posed by citizens of proposed travel-ban countries? 3. An examination of attacks in the U.S. that are inspired or enabled by ISIS. 4. An assessment of who ISIS’ American recruits are and why they sign up; 5. An assessment of how ISIS is doing; 6. An examination of what the big drivers of jihadist terrorism are; 7. A discussion of some future trends in terrorism; 8. Finally, what can be done to reduce the threat from jihadist terrorists? 1. What is the terrorism threat to the United States? The ISIS attacks in Brussels last year and in Paris in 2015 underlined the threat posed by returning Western “foreign fighters” from the conflicts in Syria and Iraq who have been trained by ISIS or other jihadist groups there. Six of the attackers in Paris were European nationals who had trained with ISIS in Syria. Yet in the United States, the threat from returning foreign fighters is quite limited. According to FBI Director James Comey, 250 Americans have gone or attempted to go to Syria. This figure is far fewer than the estimated 6,900 who have traveled to Syria from Western nations as a whole — the vast majority from Europe. -

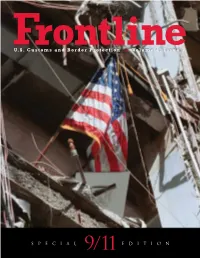

U.S. Customs and Border Protection * Volume 4, Issue 3

U.S. Customs and Border Protection H Volume 4, Issue 3 SPECIAL 9 / 11 EDITION In Memoriam H H H In honor of CBP employees who have died in the line of duty 2011 Hector R. Clark Eduardo Rojas Jr. 2010 Charles F. Collins II Michael V. Gallagher Brian A. Terry Mark F. Van Doren John R. Zykas 2009 Nathaniel A. Afolayan Cruz C. McGuire Trena R. McLaughlin Robert W. Rosas Jr. 2008 Luis A. Aguilar Jarod Dittman 2007 Julio E. Baray Eric Cabral Richard Goldstein Ramon Nevarez Jr. Robert Smith Clinton B. Thrasher David J. Tourscher 2006 Nicholas D. Greenig David N. Webb 2004 Travis Attaway George DeBates Jeremy Wilson 2003 James P. Epling H H H For a historic listing honoring federal personnel who gave their lives while securing U.S. borders, please visit CBP.gov Vol 4, Issue 3 CONTENTS H FEATURES VOL 4, ISSUE 3 4 A Day Like No Other SEPTEMBER 11, 2011 In the difficult hours and days after the SECRETARY OF HOMELAND SECURITY Sept. 11 attacks, confusion and fear Janet Napolitano turned to commitment and resolve as COMMISSIONER, the agencies that eventually would form 4 U.S. CUSTOMS AND BORDER PROTECTION CBP responded to protect America. Alan D. Bersin ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER, 16 Collective Memory OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS Melanie Roe CBP employees look back on the day that united an agency… and a nation. EDITOR Laurel Smith 16 CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 41 Attacks Redefine Eric Blum Border Security Susan Holliday Marcy Mason CBP responds to challenge by coming Jay Mayfield together to build layers of security Jason McCammack extending around the globe, upgrading its ability to keep dangerous people PRODUCTION MANAGER Tracie Parker and things out of the homeland. -

Hizb Ut-Tahrir Ideology and Strategy

HIZB UT-TAHRIR IDEOLOGY AND STRATEGY “The fierce struggle… between the Muslims and the Kuffar, has been intense ever since the dawn of Islam... It will continue in this way – a bloody struggle alongside the intellectual struggle – until the Hour comes and Allah inherits the Earth...” Hizb ut-Tahrir The Centre for Social Cohesion Houriya Ahmed & Hannah Stuart HIZB UT-TAHRIR IDEOLOGY AND STRATEGY “The fierce struggle… between the Muslims and the Kuffar, has been intense ever since the dawn of Islam... It will continue in this way – a bloody struggle alongside the intellectual struggle – until the Hour comes and Allah inherits the Earth...” Hizb ut-Tahrir The Centre for Social Cohesion Houriya Ahmed & Hannah Stuart Hizb ut-Tahrir Ideology and Strategy Houriya Ahmed and Hannah Stuart 2009 The Centre for Social Cohesion Clutha House, 10 Storey’s Gate London SW1P 3AY Tel: +44 (0)20 7222 8909 Fax: +44 (0)5 601527476 Email: [email protected] www.socialcohesion.co.uk The Centre for Social Cohesion Limited by guarantee Registered in England and Wales: No. 06609071 © The Centre for Social Cohesion, November 2009 All the Institute’s publications seek to further its objective of promoting human rights for the benefit of the public. The views expressed are those of the author, not of the Institute. Hizb ut-Tahrir: Ideology and Strategy By Houriya Ahmed and Hannah Stuart ISBN 978-0-9560013-4-4 All rights reserved The map on the front cover depicts Hizb ut-Tahrir’s vision for its Caliphate in ‘Islamic Lands’ ABOUT THE AUTHORS Houriya Ahmed is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Cohesion (CSC). -

AMERICA's CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 11

t I l AlLY r .... )k.fl ~FS A Ot:l ) lO~Ol R.. Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W. Yale-Loehr • M I GRAT i o~]~In AMERICA'S CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity after September 11 .. AUTHORS Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W . Yale-Loehr MPI gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton in the preparation of this report. Copyright © 2003 Migration Policy Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Migration Policy Institute. Migration Policy Institute Tel: 202-266-1940 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 300 Fax:202-266-1900 Washington, DC 20036 USA www.migrationpolicy.org Printed in the United States of America Interior design by Creative Media Group at Corporate Press. Text set in Adobe Caslon Regular. "The very qualities that bring immigrants and refugees to this country in the thousands every day, made us vulnerable to the attack of September 11, but those are also the qualities that will make us victorious and unvanquished in the end." U.S. Solicitor General Theodore Olson Speech to the Federalist Society, Nov. 16, 2001. Mr. Olson's wife Barbara was one of the airplane passengers murdered on September 11. America's Challenge: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 1 1 Table of Contents Foreword -

Islamic Radicalization in the Uk: Index of Radicalization

ISLAMIC RADICALIZATION IN THE UK: INDEX OF RADICALIZATION Anna Wojtowicz, (Research Assistant, ICT) Sumer 2012 ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to analyze the process of radicalization amongst British Muslims in the United Kingdom. It begins with a review of the Muslim population, demographics and community structure. Further presenting several internal and external indicators that influenced and led to radicalization of Muslim youth in Britain. The paper concludes that there is no one certainty for what causes radicalization amongst Muslims in United Kingdom. However, it is certain that Islamic radicalization and the emergence of a homegrown threat is a growing trend that jeopardizes the countries security, peace and stability. Radicalization in the United Kingdom is an existing concern that needs to be addressed and acted upon immediately. Misunderstanding or underestimating the threat may lead to further and long term consequences. * The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT). 2 I. Introduction 4 II. Background 5 History of the Muslim Community in the United Kingdom 5 Population 7 Geographical Concentration of Muslims 8 Ethnic Background 10 Age Estimate 11 Occupation and Socio-Economic Conditions 11 Religious and Cultural Aspects 13 Multiculturalism 17 Islamophobia 20 Converts 21 Case Studies –London, Birmingham, Bradford, Leeds, Leicester 22 III. Organizations 28 Organizations within the United Kingdom 28 Mosques, Koranic Schools and Islamic Centers 34 Student Groups 40 Islamic Websites and TV 43 IV. Radicalization in Britain 43 Theoretical Background and Causes of Radicalization 43 Recruitment and Radicalization: Overlook 47 Radicalization Process 49 Forms of Financing 51 Radical Groups and Movements in the UK 53 Influential Leaders in the UK 60 Inspiration and Influence from Abroad 67 Sunni 67 Shia 70 3 V. -

Interview with Max Hill, QC, Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation for the United Kingdom by Sam Mullins1

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 12, Issue 2 Policy Brief Interview with Max Hill, QC, Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation for the United Kingdom by Sam Mullins1 Abstract The following text is a transcript of an interview between the author and the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation (IRTL) for the United Kingdom, Max Hill, QC, which took place on March 9, 2018 in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany. Topics discussed included the role of the IRTL, prosecution of terrorism in the UK, returning foreign fighters, terrorism prevention and investigation measures (TPIMs), deportation of terrorism suspects, the involvement of children in terrorism, hate-preachers, and the British government’s efforts to counter non-violent extremism. The transcript has been edited for brevity. Keywords: terrorism, counter-terrorism, prosecution, security, human rights, civil liberties, United Kingdom. Introduction Security versus civil liberties. How to safeguard the population from the actions of terrorists, while at the same time preserving fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, movement and association? This is the age-old debate that lies at the heart of counter-terrorism (CT) in liberal democracies. The precise balance varies from country to country and across time but in the aftermath of attacks it is particularly likely to tip in favour of security, sometimes at the expense of certain liberties. The UK is no stranger to terrorism, but - similar to many other countries around the world - it has been on a heightened state of alert since 2014 when ISIS declared its caliphate, and last year the UK was rocked by a string of successful attacks, resulting in 36 fatalities [1]. -

The British State 'Security Syndrome' and Muslim Diversity

University of Birmingham The British State ‘Security Syndrome’ and Muslim Diversity: Challenges for Liberal Democracy in the Age of Terror Bonino, Stefano DOI: 10.1007/s11562-016-0356-4 License: Creative Commons: Attribution (CC BY) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Bonino, S 2016, 'The British State ‘Security Syndrome’ and Muslim Diversity: Challenges for Liberal Democracy in the Age of Terror', Contemporary Islam, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11562-016-0356- 4 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Al Muhajiroun and Islam4uk: the Group Behind the Ban

Developments in Radicalisation and Political Violence Al Muhajiroun and Islam4UK: The group behind the ban Catherine Zara Raymond May 2010 Developments in Radicalisation and Political Violence Developments in Radicalisation and Political Violence is a series of papers published by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR). It features papers by leading experts, providing reviews of existing knowledge and sources and/or novel arguments and insights which are likely to advance our understanding of radicalisation and political violence. The papers are written in plain English. Authors are encouraged to spell out policy implications where appropriate. Editor Prof. Harvey Rubin University of Pennsylvania Dr John Bew ICSR, King’s College London Editorial Assistant Katie Rothman International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) Editorial Board Prof. Sir Lawrence Freedman King’s College London Dr. Boaz Ganor Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya Dr. Peter Neumann King’s College London Dr Hasan Al Momani Jordan Institute of Diplomacy Contact All papers can be downloaded free of charge at www.icsr.info. To order hardcopies, please write to mail@icsr. info. For all matters related to the paper series, please write to: ICSR King’s College London, 138-142 Strand London WC2R 1HH United Kingdom © ICSR 2010 1 Summary On 2nd January 2010, Islam4UK, an off-shoot of the extremist Islamist group Al Muhajiroun, announced their intention to stage a procession through Wootton Bassett, a town which is now synonymous in the eyes of the British public with the funerals of UK soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Less than two weeks later the group was proscribed by the British government under the Terrorism Act 2000. -

Islamist Extremism in Europe

Order Code RS22211 Updated January 6, 2006 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Islamist Extremism in Europe Kristin Archick (Coordinator), John Rollins, and Steven Woehrel Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary Although the vast majority of Muslims in Europe are not involved in radical activities, Islamist extremists and vocal fringe communities that advocate terrorism exist and reportedly have provided cover for terrorist cells. Germany and Spain were identified as key logistical and planning bases for the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States. The March 2004 terrorist bombings in Madrid have been attributed to an Al Qaeda-inspired group of North Africans. And UK authorities are investigating suspected Al Qaeda support to the British perpetrators of the July 7, 2005, terrorist attacks on London. This report provides an overview of Islamist extremism in Europe, possible terrorist links, European responses, and implications for the United States. It will be updated as needed. See also CRS Report RL31612, European Counterterrorist Efforts: Political Will and Diverse Responses in the First Year after September 11, and CRS Report RL33166, Muslims in Europe: Integration in Selected Countries, by Paul Gallis. Background: Europe’s Muslim Communities1 Estimates of the number of Muslims in Europe vary widely, depending on the methodology and definitions used, and the geographical limits imposed. Excluding Turkey and the Balkans, researchers estimate that as many as 15 to 20 million Muslims live on the European continent. Muslims are the largest religious minority in Europe, and Islam is the continent’s fastest growing religion. Substantial Muslim populations exist in Western European countries, including France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium. -

Islamic Radicalism in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Implications for the EU

Islamic Radicalism in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Implications for the EU Zeyno Baran S. Frederick Starr Svante E. Cornell SILK ROAD PAPER July 2006 Islamic Radicalism in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Implications for the EU Zeyno Baran S. Frederick Starr Svante E. Cornell © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 1619 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20036 Uppsala University, Box 514, 75120 Uppsala, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Islamic Radicalism in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Implications for the EU” is a Silk Road Paper produced by the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program. The Silk Road Papers series is the Occasional Papers series of the Joint Center, published jointly on topical and timely subjects. It is edited by Svante E. Cornell, Research and Publications Director of the Joint Center. The Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and the Silk Road Studies Program is a joint transatlantic independent and externally funded research and policy center. The Joint Center has offices in Washington and Uppsala, and is affiliated with the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins University and the Department of Eurasian Studies of Uppsala University. It is the first Institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is today firmly established as a leading focus of research and policy worldwide, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders and journalists. The Joint Center aims to be at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security and development in the region; and to function as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion of the region through its applied research, its publications, teaching, research cooperation, public lectures and seminars.