Islamist Extremism in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trying Terrorists Brian S

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 34 Article 6 Issue 5 Journal of the National Security Forum 2008 Trying Terrorists Brian S. Carter-Stiglitz Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Carter-Stiglitz, Brian S. (2008) "Trying Terrorists," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 34: Iss. 5, Article 6. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol34/iss5/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Carter-Stiglitz: Trying Terrorists TRYING TERRORISTS Brian S. Carter-Stiglitz Trying terrorists in Article III courts presents a host of complications and problems. As terrorism cases come before civilian courts, prosecutors have had to wrestle with these challenges. The most significant challenge may be the tension between protecting national-security secrets and prosecuting those who threaten national security in open court. The Classified Information Procedures Act (CIPA) is the main litigation tool for dealing with these challenges. Two cases, both with Minnesota roots, demonstrate the challenges that face civil prosecution in terrorism cases. Mohammed Abdullah Warsame, a largely unknown name, is being tried in the District of Minnesota on material support charges. Michael Ward, a former assistant U.S. Attorney (AUSA) for the District of Minnesota, initially led Warsame's prosecution.' The complications caused by CIPA have already prolonged Warsame's prosecution for four years-with no end currently in sight. -

Mateen in Orlando That Killed 49 Reminds Us That Despite All These FBI Investigations, Sometimes America’S Homegrown Terrorists Will Still Slip Through the Net

The Future of Counterterrorism: Addressing the Evolving Threat to Domestic Security. House Committee on Homeland Security Committee, Counterterrorism and Intelligence Subcommittee February 28, 2017 Peter Bergen , Vice President, Director of International Security and Fellows Programs, New America; Professor of Practice, Arizona State University; CNN National Security Analyst. This testimony is organized into 8 sections 1. What is the terrorism threat to the U.S.? 2. What is the terrorism threat posed by citizens of proposed travel-ban countries? 3. An examination of attacks in the U.S. that are inspired or enabled by ISIS. 4. An assessment of who ISIS’ American recruits are and why they sign up; 5. An assessment of how ISIS is doing; 6. An examination of what the big drivers of jihadist terrorism are; 7. A discussion of some future trends in terrorism; 8. Finally, what can be done to reduce the threat from jihadist terrorists? 1. What is the terrorism threat to the United States? The ISIS attacks in Brussels last year and in Paris in 2015 underlined the threat posed by returning Western “foreign fighters” from the conflicts in Syria and Iraq who have been trained by ISIS or other jihadist groups there. Six of the attackers in Paris were European nationals who had trained with ISIS in Syria. Yet in the United States, the threat from returning foreign fighters is quite limited. According to FBI Director James Comey, 250 Americans have gone or attempted to go to Syria. This figure is far fewer than the estimated 6,900 who have traveled to Syria from Western nations as a whole — the vast majority from Europe. -

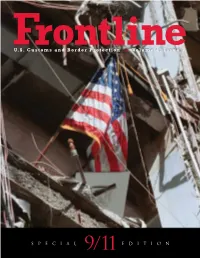

U.S. Customs and Border Protection * Volume 4, Issue 3

U.S. Customs and Border Protection H Volume 4, Issue 3 SPECIAL 9 / 11 EDITION In Memoriam H H H In honor of CBP employees who have died in the line of duty 2011 Hector R. Clark Eduardo Rojas Jr. 2010 Charles F. Collins II Michael V. Gallagher Brian A. Terry Mark F. Van Doren John R. Zykas 2009 Nathaniel A. Afolayan Cruz C. McGuire Trena R. McLaughlin Robert W. Rosas Jr. 2008 Luis A. Aguilar Jarod Dittman 2007 Julio E. Baray Eric Cabral Richard Goldstein Ramon Nevarez Jr. Robert Smith Clinton B. Thrasher David J. Tourscher 2006 Nicholas D. Greenig David N. Webb 2004 Travis Attaway George DeBates Jeremy Wilson 2003 James P. Epling H H H For a historic listing honoring federal personnel who gave their lives while securing U.S. borders, please visit CBP.gov Vol 4, Issue 3 CONTENTS H FEATURES VOL 4, ISSUE 3 4 A Day Like No Other SEPTEMBER 11, 2011 In the difficult hours and days after the SECRETARY OF HOMELAND SECURITY Sept. 11 attacks, confusion and fear Janet Napolitano turned to commitment and resolve as COMMISSIONER, the agencies that eventually would form 4 U.S. CUSTOMS AND BORDER PROTECTION CBP responded to protect America. Alan D. Bersin ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER, 16 Collective Memory OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS Melanie Roe CBP employees look back on the day that united an agency… and a nation. EDITOR Laurel Smith 16 CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 41 Attacks Redefine Eric Blum Border Security Susan Holliday Marcy Mason CBP responds to challenge by coming Jay Mayfield together to build layers of security Jason McCammack extending around the globe, upgrading its ability to keep dangerous people PRODUCTION MANAGER Tracie Parker and things out of the homeland. -

Hostile Intent and Counter-Terrorism Human Factors Theory and Application

Hostile Intent and Counter-Terrorism Human Factors Theory and Application Edited by ALEX STEDMON Coventry University, UK GLYN LAWSON The University of Nottingham, UK ASHGATE ©Alex Stedmon, Glyn Lawson and contributors 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Alex Stedmon and Glyn Lawson have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editors of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East 110 Cherry Street Union Road Suite 3-1 Famham Burlington, VT 05401-3818 Surrey, GU9 7PT USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for. ISBN: 9781409445210 (hbk) ISBN: 9781409445227 (ebk-PDF) ISBN: 9781472402103 (ebk-ePUB) MIX Paper from FSC rasponalbla tourcea Printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, wwvii.te«ro FSC* C013985 at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DTI IHD Chapter 12 Competitive Adaptation in Militant Networks: Preliminary Findings from an Islamist Case Study Michael Kenney Graduate School o f Public and International Affairs, University o f Pittsburgh, USA John Horgan International Center for the Study o f Terrorism, Pennsylvania State University, USA Cale Home Covenant College, Lookout Mountain, USA Peter Vining International Center for the Study o f Terrorism, Pennsylvania State University, USA Kathleen M. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Radical Milieus and Salafis Movements in France: Ideologies, Practices, Relationships with Society and Political Visions

MWP 2014 /13 Max Weber Programme Radical Milieus and Salafis Movements in France: Ideologies, Practices, Relationships with Society and Political Visions AuthorMohamed-Ali Author Adraouiand Author Author European University Institute Max Weber Programme Radical Milieus and Salafis Movements in France: Ideologies, Practices, Relationships with Society and Political Visions Mohamed-Ali Adraoui EUI Working Paper MWP 2014/13 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1830-7728 © Mohamed-Ali Adraoui, 2014 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract This paper deals mainly with the issue of radical Islam within French society over recent decades. More particularly, this study illustrates evolutions and the radicalization processes among some militant Islamic groups in this country since the end of the 1970s. Focusing on connections between geopolitical issues born in the Arab world and their implications within a predominantly non Muslim society, enables highlighting the centrality of some actors and currents that have been the impulse for the emergence of a radical and militant activism in France. Some specific attention is paid to Salafist movements, whether they are primarily interested in political protest or whether they desire first to break with the rest of society in order to purify their beliefs and social relations.This paper has to do with the political vision, strategies, history and sociology of Islamic radical militancy in France. -

True and False Confessions: the Efficacy of Torture and Brutal

Chapter 7 True and False Confessions The Efficacy of Torture and Brutal Interrogations Central to the debate on the use of “enhanced” interrogation techniques is the question of whether those techniques are effective in gaining intelligence. If the techniques are the only way to get actionable intelligence that prevents terrorist attacks, their use presents a moral dilemma for some. On the other hand, if brutality does not produce useful intelligence — that is, it is not better at getting information than other methods — the debate is moot. This chapter focuses on the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation technique program. There are far fewer people who defend brutal interrogations by the military. Most of the military’s mistreatment of captives was not authorized in detail at high levels, and some was entirely unauthorized. Many military captives were either foot soldiers or were entirely innocent, and had no valuable intelligence to reveal. Many of the perpetrators of abuse in the military were young interrogators with limited training and experience, or were not interrogators at all. The officials who authorized the CIA’s interrogation program have consistently maintained that it produced useful intelligence, led to the capture of terrorist suspects, disrupted terrorist attacks, and saved American lives. Vice President Dick Cheney, in a 2009 speech, stated that the enhanced interrogation of captives “prevented the violent death of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of innocent people.” President George W. Bush similarly stated in his memoirs that “[t]he CIA interrogation program saved lives,” and “helped break up plots to attack military and diplomatic facilities abroad, Heathrow Airport and Canary Wharf in London, and multiple targets in the United States.” John Brennan, President Obama’s recent nominee for CIA director, said, of the CIA’s program in a televised interview in 2007, “[t]here [has] been a lot of information that has come out from these interrogation procedures. -

AMERICA's CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 11

t I l AlLY r .... )k.fl ~FS A Ot:l ) lO~Ol R.. Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W. Yale-Loehr • M I GRAT i o~]~In AMERICA'S CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity after September 11 .. AUTHORS Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W . Yale-Loehr MPI gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton in the preparation of this report. Copyright © 2003 Migration Policy Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Migration Policy Institute. Migration Policy Institute Tel: 202-266-1940 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 300 Fax:202-266-1900 Washington, DC 20036 USA www.migrationpolicy.org Printed in the United States of America Interior design by Creative Media Group at Corporate Press. Text set in Adobe Caslon Regular. "The very qualities that bring immigrants and refugees to this country in the thousands every day, made us vulnerable to the attack of September 11, but those are also the qualities that will make us victorious and unvanquished in the end." U.S. Solicitor General Theodore Olson Speech to the Federalist Society, Nov. 16, 2001. Mr. Olson's wife Barbara was one of the airplane passengers murdered on September 11. America's Challenge: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 1 1 Table of Contents Foreword -

Discussion Paper on Approaches to Anti-Radicalization and Community Policing in the Transatlantic Space

Jonathan Paris1 23 August 2007 DISCUSSION PAPER ON APPROACHES TO ANTI-RADICALIZATION AND COMMUNITY POLICING IN THE TRANSATLANTIC SPACE Contents: 1. Comparative overview of government approaches to counter-radicalization in Europe and America 2. Comparative assessment of the successes and failures of community policing methodologies Section 1. A comparative overview of government approaches to counter- radicalization in the United Kingdom, France, Germany and the US Introduction A trend common across Europe is that there is a decrease in terrorist incidents driven by Al Qaeda (AQ) command and control in South Asia. The conviction earlier this month of the UK dirty bombers under Dhiren Barot represents one of the last of this kind of ‘outside-inside’ attack. Governments are increasingly confronted, instead, with ‘home- grown’ terrorist networks. The threat has morphed from a jihadi organization with a physical headquarters and chain of command to a jihadi movement – an ideology motivating dispersed groups internationally. Terrorists who trained in Afghanistan-based Al Qaeda (AQ) camps are still relevant actors in Europe. For instance, new evidence about the 7/7 bombers shows that Mohamed Siddique Khan and one of his co-bombers made connections with AQ in visits to Pakistan. The difference, however, is that Sid Khan sought out AQ. AQ did not seek out Sid Khan. 2 The rise of ‘home-grown’ Jihadis inspired by a movement or ideology as opposed to an organization from outside has deep implications for governments trying to graft counter- radicalization strategies: The first implication has been that developments and communities at home are watched much more closely. -

Department Ofdefense Office for the Administrative Review of The

UNCLASSIFIED Department of Defense Office for the Administrative Review of the Detention of Enemy Combatants at U.S. Naval Base Guantanamo Bay, Cuba 8 February2007 TO: PersonalRepresentative FROM CSRT ( 8 Feb 07) SUBJECT: SUMMARY OF EVIDENCE FOR COMBATANT REVIEW TRIBUNAL - AL - SHIB, RAMZI BIN Under the provisions of the Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum , dated 14 July 2006, Implementation of Combatant Status Review Tribunal Procedures for Enemy Combatants Detained at U.S. Naval Base Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, a Tribunal has been appointed to determine ifthe detainee is an enemy combatant. 2. An enemy combatant has bee defined as an individualwho was part ofor supporting the Taliban or al Qaida forces, or associatedforces that are engaged inhostilitiesagainst the United States or its coalitionpartners. This includes any personwho committeda belligerent act or has directly supported hostilities inaid ofenemy armed forces.” 3. The followingfacts supportthe determinationthat the detaineeisan enemy combatant. a. On the morning of 11 September 2001, four airliners traveling over the United States were hijacked. The flights hijacked were American Airlines Flight 11, United Airlines Flight 175, American Airlines Flight 77 and United Airlines Flight 93. At approximately 8:46 a.m., American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center, resulting in the collapse of the tower at approximately 10:25 a.m. At approximately 9:03 a.m., United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center, resulting in the collapse of the tower at approximately 9:55 a.m. At approximately 9:37 a.m., American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the southwest side of the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia. -

Download This Article As A

YOU SAY DEFENDANT, I SAY COMBATANT: OPPORTUNISTIC TREATMENT OF TERRORISM SUSPECTS HELD IN THE UNITED STATES AND THE NEED FOR DUE PROCESSAI JESSELYN A. RADACK* "[S]hould the Government determine that the defendant has engaged in conduct proscribed by the offenses now listed.., the United States may... capture and detain the defendant as an unlawful enemy com- 1 batant." - Plea Agreement of "American Taliban" John Walker Lindh "You are not an enemy combatant-you are a terrorist. You are not a 2 soldier in any way-you are a terrorist." - U.S. District Court Judge William G. Young to "shoe bomber" Richard Reid "[Enemy combatants] are not there because they stole a car or robbed a bank .... They are not common criminals. They're enemy combatants and terrorists who are being detained for acts of war against our coun- 3 try and this is why different rules have to apply." - U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld A EDITOR'S NOTE: After this article was completely written and accepted for publication, the Supreme Court ruled in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, as author Radack proposed with great foresight, that the Mathews v. Eldridge balancing test provides the appropriate analysis for the type of process that is constitutionally due to a detainee seeking to challenge his or her classification as an "enemy combatant." See Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 124 S.Ct. 2633 (2004). *A.B., Brown University, 1992; J.D., Yale Law School, 1995. The author is Founder and Execu- tive Director of the Coalition for Civil Rights and Democratic Liberties (http://www.cradl.info). -

The European Angle to the U.S. Terror Threat Robin Simcox | Emily Dyer

AL-QAEDA IN THE UNITED STATES THE EUROPEAN ANGLE TO THE U.S. TERROR THREAT Robin Simcox | Emily Dyer THE EUROPEAN ANGLE TO THE U.S. TERROR THREAT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Nineteen individuals (11% of the overall total) who committed al-Qaeda related offenses (AQROs) in the U.S. between 1997 and 2011 were either European citizens or had previously lived in Europe. • The threat to America from those linked to Europe has remained reasonably constant – with European- linked individuals committing AQROs in ten of the fifteen years studied. • The majority (63%) of the nineteen European-linked individuals were unemployed, including all individuals who committed AQROs between 1998 and 2001, and from 2007 onwards. • 42% of individuals had some level of college education. Half of these individuals committed an AQRO between 1998 and 2001, while the remaining two individuals committed offenses in 2009. • 16% of offenders with European links were converts to Islam. Between 1998 and 2001, and between 2003 and 2009, there were no offenses committed by European-linked converts. • Over two thirds (68%) of European-linked offenders had received terrorist training, primarily in Afghanistan. However, nine of the ten individuals who had received training in Afghanistan committed their AQRO before 2002. Only one individual committed an AQRO afterwards (Oussama Kassir, whose charges were filed in 2006). • Among all trained individuals, 92% committed an AQRO between 1998 and 2006. • 16% of individuals had combat experience. However, there were no European-linked individuals with combat experience who committed an AQRO after 2005. • Active Participants – individuals who committed or were imminently about to commit acts of terrorism, or were formal members of al-Qaeda – committed thirteen AQROs (62%).