Challenges and Positives Stories in Post-Apartheid Johannesburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

Sports Report 2019

Greenside High School Sports highlights and achievements 2019. Greenside High School believes strongly in the Nelson Mandela quote that says: “Sport has the power to change the world; it has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. It speaks to the youth in a language they understand. Sport can create hope, where there was once only despair. It is more powerful than governments in breaking down racial barriers. It laughs in the faces of all types of discrimination. Sport is a game of lovers.” We are truly grateful as a school that our learners are exposed to 13 sporting codes and many see themselves having career opportunities in the respective sporting codes that we offer at our school. Even though we were faced with a few challenges in the year, we have also developed and our perspectives and goals have broadened. We would like to celebrate the achievements of our learners this far in all respective codes. SPORTS HIGHLIGHTS AND ACHIEVEMNTS 2019 | s Rugby The focus in every year is to introduce the girls to appropriate technique and develop a safe and competitive environment. They had a very successful league competing with 12 schools and the U16 girls being undefeated in 2019 and our U18 only losing 1 friendly game. Almost all the girls both u16 and u18s were invited to the National Rugby Week trials. Two senior girls unfortunately did not make it in the last trials and three players were chosen for the u18 National Week Team. -

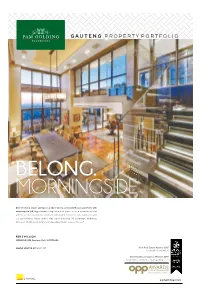

Gauteng Property Portfolio

GAUTENG PROPERTY PORTFOLIO BELONG. MORNINGSIDE One-of-a-kind, secure and spacious triple-storey, corner penthouse apartment, with uninterrupted 270-degree views. Refrigerated walk-in wine room, 4 palatial bedrooms with the wooden floor theme continued, with marble covered en suite bathrooms and a state-of-the-art home cinema with top-of-the-range AV equipment. Numerous balconies, all with views, with a heated pool and steam-room on the roof. R39.5 MILLION MORNINGSIDE, Gauteng Ref# HP1139604 WAYNE VENTER 073 254 1453 Best Real Estate Agency 2015 South Africa and Africa Best Real Estate Agency Website 2015 South Africa and Africa / pamgolding.co.za pamgolding.co.za EXERCISE YOUR FREEDOM 40KM HORSE RIDING TRAILS Our ultra-progressive Equestrian Centre, together with over 40 kilometres of bridle paths, is a dream world. Whether mastering an intricate dressage movement, fine-tuning your jump approach, or enjoying an exhilarating outride canter, it is all about moments in the saddle. The accomplished South African show jumper, Johan Lotter, will be heading up this specialised unit. A standout health feature of our Equestrian Centre is an automated horse exerciser. Other premium facilities include a lunging ring, jumping shed, warm-up arena and a main arena for show jumping and dressage events. The total infrastructure includes 36 stables, feed and wash areas, tack- rooms, office, medical rooms and groom accommodation. Kids & Teens Wonderland · Sport & Recreation · Legendary Golf · Equestrian · Restaurants & Retail · Leisure · Innovative Infrastructure -

Dainfern Classifieds

DAINFERN CLASSIFIEDS – 26 MARCH 2014 The DHA offer the Classifieds Section as a service to Homeowners and Residents and in no way do the DHA/DCC endorse any of the products and/or services displayed in this publication or do any checks on prospective employees – background checks and any other requirements are the responsibility of the Resident. REQUIRED: HOUSEMAN / GARDENER / DOMESTIC STAFF I recommend Mavuto (from Malawi) as a Housekeeper and/or GARDENER. He is looking for full time job (Monday to Friday). Live out. He has been working for our family for 6,5 years. Hard worker, honest, easy going, serious and multitasks. From Malawi. He is presently doing housekeeping, gardening, pool keeping, barman at functions , car & windows cleaner and sometimes baby-sitting during the day for us. Please contact: Nathalie [email protected] or Mavuto 072 153 9695 . Houseman /and or Gardener I recommend Mavuto (from Malawi) as a GARDENER / Painter / Houseman. He is looking for full or part time job. Live in or not. Hard worker, honest, easy going, serious and multitasks. From Malawi. He is presently doing housekeeping, gardening, pool keeping, and car & windows cleaner. Please contact: Bheki Khumalo 083 788 5067 or Mavuto 0787144946. DRIVER / GARDENER / PAINTER Victor Thandizwe Msibi is looking for full time work as a driver. He has a C1 PDP license and is also able to work in the garden and is able to undertake painting work as well. Please contact Victor on 082476 6953 or Denis Groenwald on 082 859 1472 for a reference. DAYTIME CHILD CARE / NIGHT NURSE Daytime child care / Night nurse. -

Dainfern Nature Association Booklet

Dainfern Nature Association Booklet ESTATE LIVING • WILDLIFE • TREES • BIRDS • TRAIL MAP WILDLIFE LIST A TO Z IMAGE DESCRIPTION NAME SIGHTINGS The bull frog is one of the biggest frogs and can weigh up to 2kgs. It has a large mouth, sharp teeth and very little webbing on its feet. It is quite aggressive especially the males who will defend his eggs if approached. The African bullfrog is carnivorous and will feed on anything Bull Frog it can fit into its mouth. The male only makes calls during rainy season. ESTATE LIVING • WILDLIFE • TREES • BIRDS • TRAIL MAP Found singly, in pairs or in small groups the hedgehog is mainly nocturnal. They are extremely inactive in winter however not uncommon to sight on the estate during summer. Omnivorous they will eat termites, insects, snails, frogs, lizards and small rodents. They also DNA CONTACTS Hedgehog enjoy birds eggs, certain wild fruits and any manner of vegetable matter. Monica Condy Chairlady 082 459 1539 Nocturnal and very gregarious they occur mostly in pairs or family groups. They are very Roy Lailvaux Deputy Chairman 082 553 0686 vocal using both scent and sound to communicate when out feeding at night. They are [email protected] arboreal so are excellent jumpers and rarely need to venture to the ground. They feed on Baby insects, flowers, fruits and acacia gum. They make their nests out of grass and leaves in the Linda Munro Secretary [email protected] Lesser Bush Lesser hollows or holes of trees. André Marx Bird List 083 411 7674 Christine Shaw Events/Quiz 011 469 3401 Lizards are one of biggest groups of reptiles found on earth with over 4000 species. -

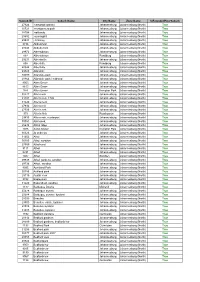

Netflorist Designated Area List.Pdf

Subrub ID Suburb Name City Name Zone Name IsExtendedHourSuburb 27924 carswald kyalami Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30721 montgomery park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28704 oaklands Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28982 sunninghill Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29534 • bramley Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8736 Abbotsford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28048 Abbotts ford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29972 Albertskroon Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 897 Albertskroon Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 29231 Albertsville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 898 Albertville Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 28324 Albertville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29828 Allandale Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30099 Allandale park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28364 Allandale park / midrand Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 9053 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8613 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 974 Allen Grove Kempton Park Johannesburg (North) True 30227 Allen neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31191 Allen’s nek, 1709 Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31224 Allens neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27934 Allens nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27935 Allen's nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 975 Allen's Nek Roodepoort Johannesburg (North) True 29435 Allens nek, rooderport Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30051 Allensnek, Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28638 -

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors by Region, Suburbs and Political Party

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS BY REGION, SUBURBS AND POLITICAL PARTY No. Councillor Name/Surname & Par Region: Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Cotact Details: ty: No: 1. Cllr. Msingathi Mazibukwana ANC G 1 Streford 5,6,7,8 and 9 Phase 1, Bongani Dlamini 078 248 0981 2 and 3 082 553 7672 011 850 1008 011 850 1097 [email protected] 2. Cllr. Dimakatso Jeanette Ramafikeng ANC G 2 Lakeside 1,2,3 and 5 Mzwanele Dloboyi 074 574 4774 Orange Farm Ext.1 part of 011 850 1071 011 850 116 083 406 9643 3. Cllr. Lucky Mbuso ANC G 3 Orange Farm Proper Ext 4, 6 Bongani Dlamini 082 550 4965 and 7 082 553 7672 011 850 1073 011 850 1097 4. Cllr. Simon Mlekeleli Motha ANC G 4 Orange Farm Ext 2,8 & 9 Mzwanele Dloboyi 082 550 4965 Drieziek 1 011 850 1071 011 850 1073 Drieziek Part 4 083 406 9643 [email protected] 5. Cllr. Penny Martha Mphole ANC G 5 Dreziek 1,2,3,5 and 6 Mzwanele Dloboyi 082 834 5352 Poortjie 011 850 1071 011 850 1068 Streford Ext 7 part 083 406 9643 [email protected] Stretford Ext 8 part Kapok Drieziek Proper 6. Shirley Nepfumbada ANC G 6 Kanama park (weilers farm) Bongani Dlamini 076 553 9543 Finetown block 1,2,3 and 5 082 553 7672 010 230 0068 Thulamntwana 011 850 1097 Mountain view 7. Danny Netnow DA G 7 Ennerdale 1,3,6,10,11,12,13 Mzwanele Dloboyi 011 211-0670 and 14 011 850 1071 078 665 5186 Mid – Ennerdale 083 406 9643 [email protected] Finetown Block 4 and 5 (part) Finetown East ( part) Finetown North Meriting 8. -

SNIS Project 2011 Working Paper

SNIS Project 2011 Working Paper Johannesburg Final Report By: C. Wanjiku Kihato, A. Spitz Swiss Network for International Studies Rue Rothschild 20 1202 Genève SUPSI University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland Laboratory of visual culture Johannesburg Final Report Caroline Wanjiku Kihato, Andy Spitz Laboratory of visual culture supsi-dacd-lcv !Campus Trevano ch-6952 Canobbio Tis project has been Tis project has been co-funded conceived and supported by the Swiss Network for by lettera27 Foundation International Studies This work is licensed under the Creative table of contents Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this 3 2.3.1 Te power of art: public art license, visit http://creativecommons.org/ and safety in Johannesburg licenses/by-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, 12 2.3.2 Background and overview Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. to public art in Johannesburg Cover image: Ilse Pahl, mosaic signage, 28 2.3.3 Tree Johannesburg Hillbrow-Berea-Yeoville, Johannesburg, photo Case studies by Caroline Wanjiku Kihato 31 2.3.3.1 Troyeville Bedtime Stories 41 2.3.3.2 Ernest Oppenheimer Park 52 2.3.3.3 Te Diepsloot public artwork Program: Diepsloot I love you... I love you not 70 2.3.4 List of public artworks Johannesburg Final Report 3 2.3.1 The power of art: public art and safety in Johannesburg Te notion of a relationship between the physical environment and the safety and well-be- ing of its users is not new. -

Fourways Nodal Analysis

FOURWAYS NODAL ANALYSIS BY: DR DIRK A PRINSLOO DIRK NICO PRINSLOO SEPTEMBER 2017 INTRODUCTION The Fourways node is experiencing strong development growth which is dominated by the extension of Fourways Mall to >170 000m². The retail offering will further be strengthened by the flagship representation of Leroy Merlin at 17 000m². With the extension and additional retail supplied, the Fourways node will be the most dominant retail market in South Africa. The super regional status of Fourways Mall will act as a catalyst for additional urban growth. The growth of the node is underpinned by the infrastructure development linked to road access and public transport. The road access will provide seamless movement from the 3 main arterial roads (William Nicol Dr, Witkoppen- & Cedar Rd) into Fouways Mall. The public transport infrastructure will include a Gautrain Station adjacent to Fourways Mall as well as a integrated taxi drop-off and pick-up in the super basement of Fourways Mall. The main purpose of the market research is to analyse the Fourways market and to compare the node with comparative and competing nodes in the broader marketplace. 2 OBJECTIVES • To analyse the relative strength of the Fourways node and to compare it with other nodes in Gauteng; • To understand the dynamics of the urban environment in Fourways; • To highlight urban market trends, changes and growth prospects; • Competitor Analysis; • To evaluate the economic conditions and growth prospects of the market; • To evaluate the micro location of Fourways Mall; • To add strategic value for the positioning of Fourways Mall and the Fourways node. 3 DEMOGRAPHICS Fourways Node • The following map shows the demarcated 8km Road Distance Area of Fourways; • The profile data clearly shows the affluent nature of this market; • The market consist of approximately 180 000 people and 75 000 households. -

Randburg Main Seat of Johannesburg North Magisterial District

# # !C # # # # # ^ !C # !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ^ # # !C # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # !C# # # ##!C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # #!C # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ### # # !C !C # # # # # !C # # ## ## !C # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # ^ # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # !C !C## # # # # # # # !C # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # ^ # !C # ## # # !C #!C # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # ## # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # -

South Africa “From Apartheid to Reconciliation”

O wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world That has such people in’t. William Shakespeare, The Tempest (V.i. 181–84) Green Line Oberstufe Exklusiv für Hessen: Topic zum Thema South Africa “From apartheid to reconciliation” Hessen Textquellenverzeichnis: 5 From Dance with a poor man’s daughter by Pamela Jooste, published by Black Swan. Reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Limited; 6–7 From Miriam’s Song by Mark Mathabane © New Millenium Books, a Division of Mathabane Books & Lectures, Oregon, USA; 8 From The Blues Is You in Me, AD Donker, Johannesburg, 1976; 9–10 Used by permission of the Nelson Mandela Foundation, Soufh Africa, www.nelsonmandela.org; 12–13 Copyright © 1998 by Desmond Tutu. Used by permission of Lynn C. Franklin Associates, Ltd. on behalf of Archbishop Desmond Tutu; 14–15 © Christopher Hope, 2005. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN.; 16 © 2004 Verlagsgruppe Handelsblatt GmbH, Düsseldorf Bildquellenverzeichnis: U1.1 Avenue Images GmbH (Fancy RF), Hamburg; U1.2 plainpicture GmbH & Co. KG (ilubi images), Hamburg; U4.1 Avenue Images GmbH (RF/Tim Pannell), Hamburg; 1.1 Avenue Images GmbH (Fancy RF), Hamburg; 2.1 Getty Images (Pettersson), München; 2.2 Fotosearch Stock Photography, Waukesha, WI; 2.3 iStockphoto (RF/Ken Sorrie), Calgary, Alberta; 3.1 Corbis, Düsseldorf; 3.2 Getty Images (Hulton Archive), München; 4.1 Getty Images (Per-Anders Pettersson), München; 5.1 shutterstock (Poleze), New York, NY; 5.2 Randomstuik – Umuzi, Cape Town; 6.1 Corbis (Gideon Mendel), Düsseldorf; 6.2 Getty Images (William F. -

GATED COMMUNITIES in SOUTH AFRICA: Comparison of Four Case Studies in Gauteng

GATED COMMUNITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA: Comparison of four case studies in Gauteng Gated communities in South Africa: Comparison of four case studies in Gauteng K Landman BP615 2004 STEP BOU / I 347 Gated communities in South Africa: cross-case study report CONTENT 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Background 4 1.2 Project Methodology 4 1.3 Structure of the document 5 2. CONTEXT 5 2.1 Socio-economic, spatial and institutional context 5 2.2 Distribution of crime in the two municipalities 8 2.3 Spatial response to crime: defensive architecture and neighbourhoods 11 2.4 Institutional response to defensive urbanism 12 3. DEVELOPMENT AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SECURITY VILLAGES AND THE ENCLOSED NEIGHBOURHOODS IN JOHANNESBURG AND TSHWANE 12 3.1 Location of case study areas in cities 12 3.2 Topology and morphology (structural organisation and form) 14 3.3 Facilities and amenities 15 3.4 Services 15 3.5 Architectural style and housing types 15 3.6 General atmosphere and quality of life 17 4. OPERATION AND MANAGEMENT 17 4.1 Resident’s or Homeowners Association 17 4.2 Private Security 18 4.3 Rules, regulations and controls 18 5. REASONS FOR THE RESPONSE OR DEVELOPMENT 19 5.1 Safety, security and the fear of crime 19 5.2 Sense of community and identity 21 5.3 Financial investment and market trend 22 5.4 Proximity to nature and specific lifestyle choice 23 CSIR Building and Construction Technology 2 Gated communities in South Africa: cross-case study report 5.5 Greater efficiency and independency 23 5.6 Status, prestige and exclusivity (elitism) 24 6.