SNIS Project 2011 Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

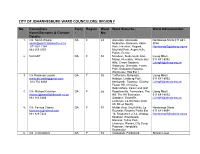

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Monuments and Museums for Post-Apartheid South Africa

Humanities 2013, 2, 72–98; doi:10.3390/h2010072 OPEN ACCESS humanities ISSN 2076-0787 www.mdpi.com/journal/humanities Article Creating/Curating Cultural Capital: Monuments and Museums for Post-Apartheid South Africa Elizabeth Rankin Department of Art History, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142, New Zealand; E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 5 February 2013; in revised form: 14 March 2013 / Accepted: 21 March 2013 / Published: 21 March 2013 Abstract: Since the first democratic elections in 1994, South Africa has faced the challenge of creating new cultural capital to replace old racist paradigms, and monuments and museums have been deployed as part of this agenda of transformation. Monuments have been inscribed with new meanings, and acquisition and collecting policies have changed at existing museums to embrace a wider definition of culture. In addition, a series of new museums, often with a memorial purpose, has provided opportunities to acknowledge previously marginalized histories, and honor those who opposed apartheid, many of whom died in the Struggle. Lacking extensive collections, these museums have relied on innovative concepts, not only the use of audio-visual materials, but also the metaphoric deployment of sites and the architecture itself, to create affective audience experiences and recount South Africa’s tragic history under apartheid. Keywords: South African museums; South African monuments; cultural capital; transformation; Apartheid Museum; Freedom Park 1. Introduction This paper considers some of the problems to be faced in the arena of culture when a country undergoes massive political change that involves a shift of power from one cultural group to another, taking South Africa as a case study. -

7.5. Identified Sites of Significance Residential Buildings Within Rosettenville (Semi-Detached, Freestanding)

7.5. Identified sites of significance_Residential buildings within Rosettenville (Semi-detached, freestanding) Introduction Residential buildings are buildings that are generally used for residential purposes or have been zoned for residential usage. It must be noted the majority of residences are over 60 years, it was therefore imperative for detailed visual study to be done where the most significant buildings were mapped out. Their significance could be as a result of them being associated to prominent figures, association with special events, design patterns of a certain period in history, rarity or part of an important architectural school. Most of the sites identified in this category are of importance in their local contexts and are representative of the historical and cultural patterns that could be discerned from the built environment. All the identified sites were given a 3A category explained below. Grading 3A_Sites that have a highly significant association with a historic person, social grouping, historic events, public memories, historical activities, and historical landmarks (should by all means be conserved) 3B_ Buildings of marginally lesser significance (possibility of senstive alteration and addition to the interior) 3C_Buildings and or sites whose significance is in large part significance that contributes to the character of significance of the environs (possibility for alteration and addition to the exterior) Summary Table of identified sites in the residential category: Site/ Description Provisional Heritage Implications -

Economics of South African Townships: a Focus on Diepsloot

A WORLD BANK STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economics of South African Townships Public Disclosure Authorized SPECIAL FOCUS ON DIEPSLOOT Public Disclosure Authorized Sandeep Mahajan, Editor Economics of South African Townships A WORLD BANK STUDY Economics of South African Townships Special Focus on Diepsloot Sandeep Mahajan, Editor WORLD BANK GROUP Washington, D.C. © 2014 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 17 16 15 14 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpreta- tions, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Mahajan, Sandeep, ed. -

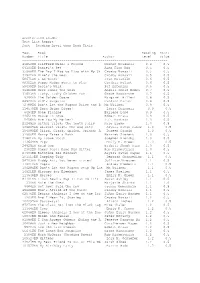

Quizinfo Level

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Sort – Reading Level then Book Title Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 41850EN Clifford Makes a Friend Norman Bridwell 0.4 0.5 64100EN Daniel's Pet Alma Flor Ada 0.5 0.5 35988EN The Day I Had to Play with My Si Crosby Bonsall 0.5 0.5 31542EN Mine's the Best Crosby Bonsall 0.5 0.5 58671EN I Am Water Jean Marzollo 0.6 0.5 88312EN Puppy Mudge Wants to Play Cynthia Rylant 0.6 0.5 59439EN Rosie's Walk Pat Hutchins 0.6 0.5 31610EN Here Comes the Snow Angela Shelf Medea 0.7 0.5 31613EN Itchy, Itchy Chicken Pox Grace Maccarone 0.7 0.5 9366EN The Golden Goose Margaret Hillert 0.8 0.5 84920EN Sid's Surprise Candace Carter 0.8 0.5 72788EN Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the B Mo Willems 0.9 0.5 114579EN Dora Helps Diego! Laura Driscoll 0.9 0.5 6494EN Gone Fishing Earlene Long 0.9 0.5 44651EN Mouse in Love Robert Kraus 0.9 0.5 5456EN Are You My Mother? P.D. Eastman 1.0 0.5 21245EN Arthur Tricks the Tooth Fairy Marc Brown 1.0 0.5 106265EN Biscuit Visits the Big City Alyssa Satin Capuc 1.0 0.5 104090EN Click, Clack, Splish, Splash: A Doreen Cronin 1.0 0.5 31600EN Harry Takes a Bath Harriet Ziefert 1.0 0.5 31601EN My Loose Tooth Stephen Krensky 1.0 0.5 113649EN Pigs Emily K. -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

Johannesburg Spatial Development Framework 2040

City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality Spatial Development Framework 2040 In collaboration with: Iyer Urban Design, UN Habitat, Urban Morphology and Complex Systems Institute and the French Development Agency City of Johannesburg: Department of Development Planning 2016 Table of Contents Glossary of Terms.................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 8 1. Foreword ....................................................................................................................................... 10 2. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 11 2.1. Existing Spatial Structure of Johannesburg and its Shortcomings ........................................ 11 2.2. Transformation Agenda: Towards a Spatially Just City ......................................................... 12 2.3. Spatial Vision: A Compact Polycentric City ........................................................................... 12 2.4. Spatial Framework and Implementation Strategy ................................................................ 17 2.4.1. An integrated natural structure .................................................................................... 17 2.4.2. Transformation Zone ................................................................................................... -

Towards Applying a Green Infrastructure Approach in the Gauteng City-Region

GCRO RESEARCH REPORT # NO. 11 TOWARDS APPLYING A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION DECEMBER 2019 Edited by Christina Culwick and Samkelisiwe Khanyile Contributions by Kerry Bobbins, Christina Culwick, Stuart Dunsmore, Anne Fitchett, Samkelisiwe Khanyile, Lerato Monama, Raishan Naidu, Gillian Sykes, Jennifer van den Bussche and Marco Vieira THE GCRO COMPRISES A PARTNERSHIP OF: TOWARDS APPLYING A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION DECEMBER 2019 Production management: Simon Chislett ISBN:978-0-6399873-6-1 Cover image: Clive Hassall e-ISBN:978-0-6399873-7-8 Peer reviewer: Dr Pippin Anderson Edited by: Christina Culwick and Samkelisiwe Khanyile Copyright 2019 © Gauteng City-Region Observatory Contributions by: Kerry Bobbins, Christina Culwick, Published by the Gauteng City-Region Observatory Stuart Dunsmore, Anne Fitchett, Samkelisiwe Khanyile, (GCRO), a partnership of the University of Johannesburg, Lerato Monama, Raishan Naidu, Gillian Sykes, Jennifer the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, van den Bussche and Marco Vieira the Gauteng Provincial Government and organised local Design: Breinstorm Brand Architects government in Gauteng (SALGA). GCRO RESEARCH REPORT # NO. 11 TOWARDS APPLYING A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE APPROACH IN THE GAUTENG CITY-REGION Edited by Christina Culwick and Samkelisiwe Khanyile Contributions by Kerry Bobbins, Christina Culwick, Stuart Dunsmore, Anne Fitchett, Samkelisiwe Khanyile, Lerato Monama, Raishan Naidu, Gillian Sykes, Jennifer van den Bussche and Marco Vieira -

15 February 2020, Cape Town

CONTEMPORARY ART 15 February 2020 CT 2020/1 2 Contemporary Art including the Property of a Collector Saturday 15 February 2020 at 6 pm Bubbly and canapés from 5 pm VEnuE abSEntEE anD TELEPHonE biDS Quay 7 Warehouse, 11 East Pier Road Tel +27 (0) 21 683 6560 V&A Waterfront, Cape Town +27 (0) 78 044 8185 GPS Co-ordinates: 33°54’05.4”S 18°25’27.9”E [email protected] PREVIEW payMEnt Thursday 13 and Friday 14 February Tel +27 (0) 21 683 6560 from 10 am to 5 pm +27 (0) 11 728 8246 Saturday 15 February from 10 am to 6 pm [email protected] LEctuRES anD WalKaboutS conDition REpoRTS See page 10 [email protected] ENQuiRIES anD cataloGUES www.straussart.co.za +27 (0) 21 683 6560 +27 (0) 78 044 8185 contact nuMBERS DURinG PREVIEW anD auction ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE: R220.00 Tel +27 (0) 78 044 8185 All lots are sold subject to the conditions of business +27 (0) 72 337 8405 printed at the back of ths catalogue PUBLIC AUCTION BY DIRECTORS F KILBOURN (EXECUTIVE CHAIRPERSON), E BRADLEY, CB STRAUSS, C WIESE, J GINSBERG, C WELZ, V PHILLIPS (MD), B GENOVESE (MD), AND S GOODMAN (EXECUTIVE) 4 Contents 3 Sale Information 6 Directors, Specialists, Administration 8 Map and Directions 9 Buying at Strauss & Co 10 Lectures and Walkabouts 12 Contemporary Art Auction at 6pm Lots 1–102 121 Conditions of Business 125 Bidding Form 126 Shipping Instruction Form 132 Artist Index PAGE 2 Lot 21 Yves Klein Table IKB® (detail) LEFT Lot 53 William Kentridge Small Koppie 2 (detail) From the Property of a Collector 5 Directors Specialists Administration -

Sports Report 2019

Greenside High School Sports highlights and achievements 2019. Greenside High School believes strongly in the Nelson Mandela quote that says: “Sport has the power to change the world; it has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. It speaks to the youth in a language they understand. Sport can create hope, where there was once only despair. It is more powerful than governments in breaking down racial barriers. It laughs in the faces of all types of discrimination. Sport is a game of lovers.” We are truly grateful as a school that our learners are exposed to 13 sporting codes and many see themselves having career opportunities in the respective sporting codes that we offer at our school. Even though we were faced with a few challenges in the year, we have also developed and our perspectives and goals have broadened. We would like to celebrate the achievements of our learners this far in all respective codes. SPORTS HIGHLIGHTS AND ACHIEVEMNTS 2019 | s Rugby The focus in every year is to introduce the girls to appropriate technique and develop a safe and competitive environment. They had a very successful league competing with 12 schools and the U16 girls being undefeated in 2019 and our U18 only losing 1 friendly game. Almost all the girls both u16 and u18s were invited to the National Rugby Week trials. Two senior girls unfortunately did not make it in the last trials and three players were chosen for the u18 National Week Team. -

Gauteng Property Portfolio

GAUTENG PROPERTY PORTFOLIO BELONG. MORNINGSIDE One-of-a-kind, secure and spacious triple-storey, corner penthouse apartment, with uninterrupted 270-degree views. Refrigerated walk-in wine room, 4 palatial bedrooms with the wooden floor theme continued, with marble covered en suite bathrooms and a state-of-the-art home cinema with top-of-the-range AV equipment. Numerous balconies, all with views, with a heated pool and steam-room on the roof. R39.5 MILLION MORNINGSIDE, Gauteng Ref# HP1139604 WAYNE VENTER 073 254 1453 Best Real Estate Agency 2015 South Africa and Africa Best Real Estate Agency Website 2015 South Africa and Africa / pamgolding.co.za pamgolding.co.za EXERCISE YOUR FREEDOM 40KM HORSE RIDING TRAILS Our ultra-progressive Equestrian Centre, together with over 40 kilometres of bridle paths, is a dream world. Whether mastering an intricate dressage movement, fine-tuning your jump approach, or enjoying an exhilarating outride canter, it is all about moments in the saddle. The accomplished South African show jumper, Johan Lotter, will be heading up this specialised unit. A standout health feature of our Equestrian Centre is an automated horse exerciser. Other premium facilities include a lunging ring, jumping shed, warm-up arena and a main arena for show jumping and dressage events. The total infrastructure includes 36 stables, feed and wash areas, tack- rooms, office, medical rooms and groom accommodation. Kids & Teens Wonderland · Sport & Recreation · Legendary Golf · Equestrian · Restaurants & Retail · Leisure · Innovative Infrastructure -

A Case Study of Urban Renewal for the Presidential 10 Year Review Project

Alexandra: A Case study of urban renewal for the Presidential 10 year review project June 2003 Review by the Human Sciences Research Council (Democracy and Governance Programme) In association with Indlovo Link Dr. Marlene Roefs, Democracy and Governance, HSRC Mr. Vino Naidoo, Democracy and Governance, HSRC Mr. Mike Meyer, Indlovo Link Ms. Joan Makalela, Democracy and Governance, HSRC (Photography by Jankie Matlala) Our sincere appreciation goes to the City of Johannesburg (Region 7 Office), including the People’s Centre Information Services; the Social, Physical and LED Clusters of the ARP; and members of the public. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...............................................................................................................................3 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................................9 1.1 Urban Renewal Programme .........................................................................................10 1.2 Description of Alexandra.................................................................................................13 1.3 Population profile .............................................................................................................15 1.4 Overview of Recent History............................................................................................16 2. Development Planning Objectives.......................................................................................20