Bagpipes CMYK Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Following the Science

November 2020 Following the Science: A systematic literature review of studies surrounding singing and brass, woodwind and bagpipe playing during the COVID-19 pandemic Authors: John Wallace, Lio Moscardini, Andrew Rae and Alan Watson Music Education MEPGScotland Partnership Group MEPGScotland.org @MusicEducation10 Table of Contents Overview 1 Introduction Research Questions Research Method 2 Systematic Review Consistency Checklist Results 5 Thematic Categories Discussion 7 Breathing Singing Brass playing Woodwind playing Bagpipes Summary Conclusions 14 Recommended measures to mitigate risk 15 Research Team 17 Appendix 18 Matrix of identified papers References 39 Overview Introduction The current COVID-19 situation has resulted in widespread concern and considerable uncertainty relating to the position of musical performance and in particular potential risks associated with singing and brass, woodwind and bagpipe playing. There is a wide range of advice and guidance available but it is important that any guidance given should be evidence- based and the sources of this evidence should be known. The aim of the study was to carry out a systematic literature review in order to gather historical as well as the most current and relevant information which could provide evidence-based guidance for performance practice. This literature was analysed in order to determine the evidence of risk attached to singing and brass , woodwind and bagpipe playing, in relation to the spread of airborne pathogens such as COVID-19, through droplets and aerosol. -

Common Reed Phragmites Australis (Cav.) Trin. Ex Steud. Grass Family (Poaceae)

FACT SHEET: GIANT REED Common Reed Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. Grass family (Poaceae) NATIVE RANGE Eurasia DESCRIPTION Common reed, or Phragmites, is a tall, perennial grass that can grow to over 15 feet in height. In North America, both native phragmites (Phragmites australis ssp. americanus Saltonstall, P.M. Peterson & Soreng) and introduced subspecies are found. Introduced Phragmites forms dense stands which include both live stems and standing dead stems from previous year’s growth. Leaves are elongate and typically 1-1.5 inches wide at their widest point. Flowers form bushy panicles in late July and August and are usually purple or golden in color. As seeds mature, the panicles begin to look “fluffy” due to the hairs on the seeds and they take on a grey sheen. Below ground, Phragmites forms a dense network of roots and rhizomes which can go down several feet in depth. The plant spreads horizontally by sending out rhizome runners which can grow 10 or more feet in a single growing season if conditions are optimal. Please see the table below for information on distinguishing betweeen native and introduced Phragmites. ECOLOGICAL THREAT Once introduced Phragmites invades a site it quickly can take over a marsh community, crowding out native plants, changing marsh hydrology, altering wildlife habitat, and increasing fire potential. Its high biomass blocks light to other plants and occupies all the growing space belowground so plant communities can turn into a Phragmites monoculture very quickly. Phragmites can spread both by seed dispersal and by vegetative spread via fragments of rhizomes that break off and are transported elsewhere. -

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents 4 President’s Message Music 5 Editorial 33 Jimmy Tweedie’s Sealegs 6 Letters to the Editor 43 Report for the Reviews Executive Secretary 34 Review of Gibson Pipe Chanter Spring 2015 35 The Campbell Vol. 44, No. 1 Basics Tunable Chanter 9 Snare Basics: Snare FAQ THE VOICE is the official publication of the Eastern United 11 Bass & Tenor Basics: Semiquavers States Pipe Band Association. Writing a Basic Tenor Score 35 The Making of the 13 Piping Basics: “Piob-ogetics” Casco Bay Contest John Bottomley 37 Pittsburgh Piping EDITOR [email protected] Features Society Reborn 15 Interview Shawn Hall 17 Bands, Games Come Together Branch Notes ART DIRECTOR 19 Willie Wows ‘Em 39 Southwest Branch [email protected] 21 The Last Happy Days – 39 Metro Branch Editorial Inquiries/Letters the Great Highland Bagpipe 40 Ohio Valley Branch THE VOICE in JFK’s Camelot 41 Northeast Branch [email protected] ADVERTISING INQUIRIES John Bottomley [email protected] THE VOICE welcomes submissions, news items, and ON THE COVER: photographs. Please send your Derek Midgley captured the joy submissions to the email above. of early St. Patrick’s parades in the northeast with this photo of Rich Visit the EUSPBA online at www.euspba.org Harvey’s pipe at the Belmar NJ event. ©2014 Eastern United States Pipe Band EUSPBA MEMBERS receive a subscription to THE VOICE paid for, in part, Association. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced or transmitted by their dues ($8 per member is designated for THE VOICE). -

The Secret of the Bagpipes: Controlling the Bag. Techniques, Skill and Musicality

CASSANDRE BALOSSO-BARDIN,a AUGUSTIN ERNOULT,b PATRICIO DE LA CUADRA,c BENOÎT FABRE,b AND ILYA FRANCIOSIb The Secret of the Bagpipes: Controlling the Bag. Techniques, Skill and Musicality. hen interviewed about the technique as the Greek tsampouna or the Tunisian mizwid) to of the bag, bagpipe maker and award- a fully chromatic scale over two octaves (the uilleann winning Galician piper Cristobal Prieto pipes from Ireland and some Northumbrian small- Wsaid that. ‘the handling of the bag is one of the most pipes chanters). Bagpipes in their simplest form are important things. The secret of the bagpipes is how composed of a bag with a blowpipe and a melodic one uses the bag […] You need a lot of coordination: pipe (hereafter referred to as the chanter).2 Other blowing, fingers […] it depends on the arm, the pipes can then be added such as a second melodic pressure of the air. The [finger] technique is much pipe, semi-melodic pipes or drones.3 The blowpipe simpler. Everyone blows all over the place when they is usually, but not always, fitted with a small valve start to play. It’s like a car: you have to think how you in order to prevent the air from leaving the bag. In are going to do all of this at the same time. The use models without this system, the piper uses his/her of the bag is the most important aspect, even more tongue to prevent the air from escaping whilst s/he than the fingers, [or] velocity’.1 breathes in. -

Woodwind Family

Woodwind Family What makes an instrument part of the Woodwind Family? • Woodwind instruments are instruments that make sound by blowing air over: • open hole • internal hole • single reeds • double reed • free reeds Some woodwind instruments that have open and internal holes: • Bansuri • Daegeum • Fife • Flute • Hun • Koudi • Native American Flute • Ocarina • Panpipes • Piccolo • Recorder • Xun Some woodwind instruments that have: single reeds free reeds • Clarinet • Hornpipe • Accordion • Octavin • Pibgorn • Harmonica • Saxophone • Zhaleika • Khene • Sho Some woodwind instruments that have double reeds: • Bagpipes • Bassoon • Contrabassoon • Crumhorn • English Horn • Oboe • Piri • Rhaita • Sarrusaphone • Shawm • Taepyeongso • Tromboon • Zurla Assignment: Watch: Mr. Gendreau’s woodwind lesson How a flute is made How bagpipes are made How a bassoon reed is made *Find materials in your house that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) can use to make a woodwind (i.e. water bottle, straw and cup of water, piece of paper, etc). *Find some other materials that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) you can make a different woodwind instrument. *What can you do to change the sound of each? *How does the length of the straw effect the sound it makes? *How does the amount of water effect the sound? When you’re done, click here for your “ticket out the door”. Some optional videos for fun: • Young woman plays music from “Mario” on the Sho • Young boy on saxophone • 9 year old girl plays the flute. -

Reed Instruments About Reeds

Reed Instruments About Reeds A reed is a thin elastic strip of cane fixed at one end and free at the other. It is set into vibration by moving air. Reeds are the sound generators in the instruments described below. Cane reeds are built as either double or single reeds. A double reed consists of two pieces of cane carved and bound into a hollow, round shape at one end and flattened out and shaved thin at the other. The two pieces are tied together to form an channel. The single reed is a piece of cane shaved at one end and fastened at the other to a mouthpiece. Single Reed Instruments Clarinet: A family of single reed instruments with mainly a cylindrical bore. They are made of grenadilla (African blackwood) or ebonite, plastic, and metal. Clarinets are transposing instruments* and come in different keys. The most common ones used in orchestras are the clarinet in A and the clarinet in Bb. When a part calls for a clarinet in A, the player may either double -i.e. play the clarinet in A, or play the clarinet in Bb and transpose* the part as he plays. During the time of Beethoven, the clarinet in C was also in use and players were expected to be able to play all three instruments when required. All clarinets are notated in the treble clef and have approximately the same written range: E below middle C to c´´´´ (C five ledger lines above the staff). Bass Clarinet: A member of the clarinet family made of wood, which sounds an octave lower than the Clarinet in Bb. -

Handbook - Residence - 2019-20

STUDENT SERVICES MISSION 1 WELCOME TO GREBEL A warm welcome to all who have decided to make Grebel their University of Waterloo ‘home’ for the next term or two or three! All of us – faculty, staff and administrators are thrilled to have you a part of this intentional community where we strive to create a residential experience that fosters: Opportunities for students to explore and engage with Christian faith, practice, history, and values particularly as they are understood in the Anabaptist-Mennonite tradition; Opportunities for students to engage in the ‘dialogue of life’ with people who have diverse world views and faith expressions; The exploration of life-meaning and value questions leading to action; Intellectually stimulating conversations that integrate textbook, classroom and life experiences; A respectful and enjoyable living environment that enables students to study, learn and grow to their full potential; Community practises such as: o Honesty and openness in personal relationships o Respectful interactions with all o Interaction and dialogue between students, faculty and staff o Interdependence of people and enduring friendships o Leadership development o The resolution of conflict through reconciliation and group counsel. Grebel is an affirming community and believes all people deserve to be treated with respect. We are guided by the Ontario Human Rights Code which states, “Every person has a right to equal treatment… without discrimination because of 2 race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, age, marital status, family status or disability. (excerpt from Ontario Human Rights Code https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90h19). -

The Devolution of the Shepherd Trumpet and Its Seminal

Special Supplement to the International Trumpet Guild ® Journal to promote communications among trumpet players around the world and to improve the artistic level of performance, teaching, and literature associated with the trumpet ADDEN DUM TO “THE DEVOLUTI ON OF THE SHEPHERD TRUMPET AND ITS SEMINAL IMP ORTANCE IN MUSIC HISTORY” BY AINDRIAS HIRT January 2015 • Revision 2 The International Trumpet Guild ® (ITG) is the copyright owner of all data contained in this file. ITG gives the individual end-user the right to: • Download and retain an electronic copy of this file on a single workstation that you own • Transmit an unaltered copy of this file to any single individual end-user, so long as no fee, whether direct or indirect is charged • Print a single copy of pages of this file • Quote fair use passages of this file in not-for-profit research papers as long as the ITGJ, date, and page number are cited as the source. The International Trumpet Guild ® prohibits the following without prior writ ten permission: • Duplication or distribution of this file, the data contained herein, or printed copies made from this file for profit or for a charge, whether direct or indirect • Transmission of this file or the data contained herein to more than one individual end-user • Distribution of this file or the data contained herein in any form to more than one end user (as in the form of a chain letter) • Printing or distribution of more than a single copy of the pages of this file • Alteration of this file or the data contained herein • Placement of this file on any web site, server, or any other database or device that allows for the accessing or copying of this file or the data contained herein by any third party, including such a device intended to be used wholly within an institution. -

History of the Bagpipe There Is No Instrument That Brings As Much Gravitas and Solemnity to a Remembrance Day Ceremony As the Bagpipe

Arbourside Court Newsletter November 2016 The Arby The official News of Arbourside Court History of the Bagpipe There is no instrument that brings as much gravitas and solemnity to a Remembrance Day ceremony as the bagpipe. Although it is an instrument that we most closely associ- ate with the British Isles, it is of ancient origin that has become the symbol of war and its casualties. The evidence for pre-Roman era bagpipes is still uncertain but several textual and visual clues have been suggested. The Oxford History of Music says that a sculpture of bagpipes has been found on a Hittite slab at Euyuk in the Middle East, dated to 1000 BC. Several authors identify the Ancient Greek askaulos (askos – wine-skin, aulos – reed pipe) with the bagpipe. 1st Century writing records that a roman emperor, possibly Nero, could play a pipe (tibia, Roman reedpipes similar to Greek and Etruscan instruments) with his mouth as well as by tucking a bladder be- neath his armpit. Spread and development in Europe In the early part of the second millennium, bagpipes or its close cousins began to appear more frequently in artworks. The Cantigas de Santa Maria, written in Castile in the mid-13th centu- ry, depicts several types of bagpipes.Though evidence of bagpipes in the British Isles prior to the 14th century is contested, bagpipes are explicitly mentioned in The Canterbury Tales (written around 1380): A baggepype wel coude he blowe and sowne, /And ther-with-al he broghte us out of towne. Actual examples of bagpipes from before the 18th century are extremely rare; however, a sub- stantial number of paintings, carvings, engravings, manuscript illuminations, and so on survive. -

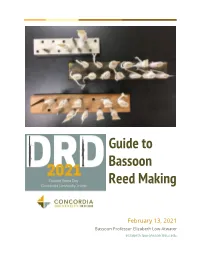

Guide to Bassoon Reed Making

Guide to Bassoon Reed Making February 13, 2021 Bassoon Professor Elizabeth Low-Atwater [email protected] 1 Arundo Donax From the Wikipedia Page: Arundo donax, giant cane, is a tall perennial cane. It is one of several so-called reed species. It has several names including carrizo, arundo, Spanish cane, Colorado river reed, wild cane, and giant reed. Arundo donax grows in damp soils, either fresh or moderately saline, and is native to the Mediterranean Basin and Middle East, and probably also parts of Africa and the southern Arabian Peninsula. Tube Cane Cane is selected based on its diameter thickness of 24-26mm and is measured with a caliper tool. After cut to the correct lengths, the cane then sits for an average of 1 to 2 years to cure. 2 Steps from Cane to Finished Reed There are essentially six stages of the reed making process. We will dive into each of the steps specifically but laid out they are: 1. Gouged 2. Shaped 3. Profiled 4. Formed Tube (Cocoons) 5. Blank: Wired/Sealed/Turbaned 6. Finished Reed: Cut tip & Scraped 3 Split and Gouged Cane From the tube cane, it is then split into 3 to 4 pieces soaked overnight, and taken through a pre-gouger and gouger to remove the inside soft parts of the cane. Pre Gouger Gouger Shaping In this process, the gouged piece of cane is soaked for 2-3 hours then placed into a straight shaper. The metal shaper helps act as a guide to cut out the given shape. This is done with a ceramic knife, x-acto knife, and a diamond file. -

Arundo Donax Near Big Bend National Park, Texas (Left), and Near Eagle Pass, Texas, Along the Rio Grande (Right)

Weed Risk Assessment for Arundo United States donax L. (Poaceae) – Giant reed Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service June 14, 2012 Version 1 Aerial view of Arundo donax near Big Bend National Park, Texas (left), and near Eagle Pass, Texas, along the Rio Grande (right). Source: Photographs taken by John Goolsby and obtained from http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/AR/archive/jul09/arundo0709.htm. Agency Contact: Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory Center for Plant Health Science and Technology Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service United States Department of Agriculture 1730 Varsity Drive, Suite 300 Raleigh, NC 27606 Weed Risk Assessment for Arundo donax Introduction Plant Protection and Quarantine (PPQ) regulates noxious weeds under the authority of the Plant Protection Act (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000) and the Federal Seed Act (7 U.S.C. § 1581-1610, 1939). A noxious weed is “any plant or plant product that can directly or indirectly injure or cause damage to crops (including nursery stock or plant products), livestock, poultry, or other interests of agriculture, irrigation, navigation, the natural resources of the United States, the public health, or the environment” (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000). We use weed risk assessment (WRA) —specifically, the PPQ WRA model1—to evaluate the risk potential of plants, including those newly detected in the United States, those proposed for import, and those emerging as weeds elsewhere in the world. Because our WRA model is geographically and climatically neutral, it can be used to evaluate the baseline invasive/weed potential of any plant species for the entire United States or any area within it.