UTM Clarinet Studio Getting Reeds to Play Their Best

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Common Reed Phragmites Australis (Cav.) Trin. Ex Steud. Grass Family (Poaceae)

FACT SHEET: GIANT REED Common Reed Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. Grass family (Poaceae) NATIVE RANGE Eurasia DESCRIPTION Common reed, or Phragmites, is a tall, perennial grass that can grow to over 15 feet in height. In North America, both native phragmites (Phragmites australis ssp. americanus Saltonstall, P.M. Peterson & Soreng) and introduced subspecies are found. Introduced Phragmites forms dense stands which include both live stems and standing dead stems from previous year’s growth. Leaves are elongate and typically 1-1.5 inches wide at their widest point. Flowers form bushy panicles in late July and August and are usually purple or golden in color. As seeds mature, the panicles begin to look “fluffy” due to the hairs on the seeds and they take on a grey sheen. Below ground, Phragmites forms a dense network of roots and rhizomes which can go down several feet in depth. The plant spreads horizontally by sending out rhizome runners which can grow 10 or more feet in a single growing season if conditions are optimal. Please see the table below for information on distinguishing betweeen native and introduced Phragmites. ECOLOGICAL THREAT Once introduced Phragmites invades a site it quickly can take over a marsh community, crowding out native plants, changing marsh hydrology, altering wildlife habitat, and increasing fire potential. Its high biomass blocks light to other plants and occupies all the growing space belowground so plant communities can turn into a Phragmites monoculture very quickly. Phragmites can spread both by seed dispersal and by vegetative spread via fragments of rhizomes that break off and are transported elsewhere. -

Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur Gmbh the World's Oldest Accordion

MADE IN GERMANY Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH The world’s oldest accordion manufacturer | Since 1852 Our “Weltmeister” brand is famous among accordion enthusiasts the world over. At Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH, we supply the music world with Weltmeister solo, button, piano and folklore accordions, as well as diatonic button accordions. Every day, our expert craftsmen and accordion makers create accordions designed to meet musicians’ needs. And the benchmark in all areas of our shop is, of course, quality. 160 years of instrument making at Weltmeister Akkordeon Manufaktur GmbH in Klingenthal, Germany, are rooted in sound craftsmanship, experience and knowledge, passed down carefully from master to apprentice. Each new generation that learns the trade of accordion making at Weltmeister helps ensure the longevity of the company’s incomparable expertise. History Klingenthal, a centre of music, is a small town in the Saxon Vogtland region, directly bordering on Bohemia. As early as the middle of the 17th century, instrument makers settled down here, starting with violin makers from Bohemia. Later, woodwinds and brasswinds were also made here. In the 19th century, mouth organ ma- king came to town and soon dominated the townscape with a multitude of workshops. By the year 1840 or thereabouts, this boom had turned Klingenthal into Germany’s largest centre for the manufacture of mouth organs. Production consolidation also had its benefits. More than 30 engineers and technicians worked to stre- Accordion production started in 1852, when Adolph amline the instrument making process and improve Herold brought the accordion along from Magdeburg. quality and customer service. A number of inventions At that time the accordion was a much simpler instru- also came about at that time, including the plastic key- ment, very similar to the mouth organ, and so it was board supported on two axes and the plastic and metal easily reproduced. -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

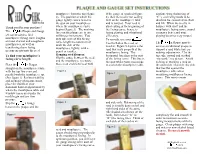

Thank You for Your Purchase! the ® Plaque and Gauge Set Can Be Used to Find Mouthpiece Facing Curve Lengths on Most Clarinet A

mouthpiece from the top (figure If the gauge is crooked (figure airplane wing (balancing of 2). The position at which the 4), then the reed is not sealing “C”), each wing needs to be ® gauge lightly comes to rest is well on the mouthpiece table identical for consistent air-flow MADE IN USA the spot on your mouthpiece and is warped. Your reed is and lift. When the reed is in Thank you for your purchase! where the mouthpiece curve also leaking at the beginning of balance with itself and the begins (figure 3). The marking the facing curve, hence, is mouthpiece facing curve, sound The ® Plaque and Gauge lines on the plaque are in one losing playing and vibrational resonates better and your set can be used to find millimeter increments. You efficiency. playing becomes very natural. mouthpiece facing curve lengths may take note of this facing To remedy, use your ® on most clarinet and saxophone curve length measurement or Tool to flatten the reed, as The ® Plaque may be mouthpieces, as well as mark the side of the transferring those facing needed. Figure 5 depicts a flat used as a traditional plaque to mouthpiece, lightly, with a reed that seals properly at the support a reed while you are measurements onto the reed. pencil or marker. mouthpiece facing. The making adjustments. Use the To find your mouthpiece’s Gauging reed flatness: horizontal line depicts the start top side, curved end marked facing curve length: Slip the gauge between the reed of the facing curve. This line is “tip work,” see picture. -

Bishop Scott Boys' School

BISHOP SCOTT BOYS’ SCHOOL (Affiliated to CBSE, New Delhi) Affiliation No.: 330726, School Campus: Chainpur, Jaganpura, By-Pass, Patna 804453. Phone Number: 7061717782, 9798903550. , Web: www.bishopscottboysschool.com Email: [email protected] STUDY COURSE MATERIAL ENGLISH SESSION-2020-21 CLASS- IX Ch 2- The Sound of Music. Part I - (Evelyn Glennie Listens to Sound without Hearing It) By Deborah Cowley Part I. Word meanings. 1. Profoundly deaf: absolutely deaf. 2. specialist: a doctor specializing in a particular part of the body. 3. Deteriorated: worsened, reduces. 4. Urged: requested. 5. coveted: much desired 6. replicating: making a copy of something 7. yearning – longing, having a desire for something 8. devout: believing strongly in a religion and obeying its laws and following its practices Summary. Evelyn Glennie is a multi – percussionist. She has attained mastery over almost a thousand musical instruments despite being hearing – impaired. She learnt to feel music through the body instead of hearing it through the ears. When Evelyn was eleven years old, it was discovered that she had lost her hearing power due to nerve damage. The specialist advised that she wear hearing aids and be sent to a school for the deaf. On the contrary, Evelyn was determined to lead a normal life and follow her interest in music. Although she was discouraged by her teachers, her potential was noticed by master percussionist, Ron Forbes. He guided Evelyn to feel music some other way than to hear it through her ears. This worked well for Evelyn and she realized that she could sense different sounds through different parts of her body. -

Physical Study of Double-Reed Instruments for Application to Sound-Synthesis André Almeida, Christophe Vergez, René Causse, Xavier Rodet

Physical study of double-reed instruments for application to sound-synthesis André Almeida, Christophe Vergez, René Causse, Xavier Rodet To cite this version: André Almeida, Christophe Vergez, René Causse, Xavier Rodet. Physical study of double-reed instru- ments for application to sound-synthesis. International Symposium in Musical Acoustics, Dec 2002, Mexico, Mexico. pp.1-1. hal-01161426 HAL Id: hal-01161426 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01161426 Submitted on 8 Jun 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Physical study of double-reed instruments for application to sound-synthesis Andre´ Almeida∗, Christophe Vergezy, Rene´ Causse´∗, Xavier Rodet∗ ∗IRCAM, Centre Pompidou/CNRS, 1 Place Igor Stravinsky, 75004 Paris, France yLMA, CNRS, 31 Chemin Joseph Aiguier, 13402 cedex 20 Marseille, France Physical models for most reed instruments have been studied for about 30 years and relatively simple models are enough to describe the main features of their behavior. These general models seem to be valid for all members of the family, yet the sound of a clarinet is distinguishable from the sound of a saxophone or an oboe. Though the conical bore of an oboe or a bassoon has a strong effect over the timbre difference, it doesn’t seem to be a sufficient explanation for the specific character of these double-reed instruments. -

REED HARDNESS TIPS REED SELECTION TIPS TIPBOOK TIP 11: French & American Cuts Butt Vamp There Are Two Style of Reeds: French Cut and American Cut

REED HARDNESS TIPS REED SELECTION TIPS TIPBOOK TIP 11: French & American Cuts butt vamp There are two style of reeds: French cut and American cut. French TIPBOOK TIP: 01 Hardness cut reeds, mainly used by classical saxophonists, have a thinner tip heart tip and are a bit thicker in the heart area. Reeds with an American cut The main difference from one reed to another is how soft or hard usually feature a slightly thicker tip and less heart, producing a they feel. Reeds are often classified with numbers, e.g., from 2 to table fuller, focused sound. 4 in half strengths. The higher the number, the harder or more resistant the reed plays. TIPBOOK TIP 12: French Filed Cut TIPBOOK TIP: 02 Names Instead of Numbers TIPBOOK TIP 06: Not Equally Hard Reeds with a file cut or “double cut” have an Some reeds are measured with words instead of numbers. The Because cane is a natural product, each piece of cane will vary extra strip of the bark removed in a straight line, hardness can be indicated as Soft (S), Medium soft, Medium (M), slightly in resistance despite being cut identically. As a result, ten just below the vamp area. This allows for extra Medium hard, or Hard (H). There are also some models like Rico’s reeds of the same strength from inside the same box will not be flexibility and a fast response. Select Jazz™ that let you fine tune the strength into smaller equally hard. A box of 2.5 reeds may contain some harder and increments such as 2 Soft, 2 Medium, or 2 Hard (2S, 2M, 2H, 3S, softer 2.5 reeds. -

Instrument Descriptions

RENAISSANCE INSTRUMENTS Shawm and Bagpipes The shawm is a member of a double reed tradition traceable back to ancient Egypt and prominent in many cultures (the Turkish zurna, Chinese so- na, Javanese sruni, Hindu shehnai). In Europe it was combined with brass instruments to form the principal ensemble of the wind band in the 15th and 16th centuries and gave rise in the 1660’s to the Baroque oboe. The reed of the shawm is manipulated directly by the player’s lips, allowing an extended range. The concept of inserting a reed into an airtight bag above a simple pipe is an old one, used in ancient Sumeria and Greece, and found in almost every culture. The bag acts as a reservoir for air, allowing for continuous sound. Many civic and court wind bands of the 15th and early 16th centuries include listings for bagpipes, but later they became the provenance of peasants, used for dances and festivities. Dulcian The dulcian, or bajón, as it was known in Spain, was developed somewhere in the second quarter of the 16th century, an attempt to create a bass reed instrument with a wide range but without the length of a bass shawm. This was accomplished by drilling a bore that doubled back on itself in the same piece of wood, producing an instrument effectively twice as long as the piece of wood that housed it and resulting in a sweeter and softer sound with greater dynamic flexibility. The dulcian provided the bass for brass and reed ensembles throughout its existence. During the 17th century, it became an important solo and continuo instrument and was played into the early 18th century, alongside the jointed bassoon which eventually displaced it. -

A Pedagogical Utilisation of the Accordion to Study the Vibration Behaviour of Free Reeds

A PEDAGOGICAL UTILISATION OF THE ACCORDION TO STUDY THE VIBRATION BEHAVIOUR OF FREE REEDS PACS REFERENCE: 4310.Sv Llanos-Vázquez, R.1; Elejalde-García, M.J.1; Macho-Stadler, E.1; Alonso-Moral, J.2 1Dpto. Física Aplicada 1. Escuela Superior de Ingenieros. UPV/EHU. Address: Alameda de Urquijo s.n., 48013 Bilbao, Spain. Tel: 34-946014256. Fax: 34-946014178. E-mail: [email protected] 2Conservatorio Superior de Música Juan Crisóstomo de Arriaga Address: General Concha 20, 48010 Bilbao, Spain. Tel: 34-944412136. Fax: 34-946014178. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is concerned primarily with an educational approach to the accordion sound generation mechanisms. Accordions are made to sound by buzzing a thin steel tongue, which is attached to one side of a metal plate containing an aperture through which the reed tongue can actually pass. The accordion utilises the free reed principle, is hand-held and is powered by bellows. The aim of this work is to present the pedagogical steps that focus on the knowledge of free reed behaviour and the pressure forces that excite the reed vibration. INTRODUCTION The term Accordion is the proper generic term for all members of a complex family of free-reed aerophones. The accordion consists of a series of air-actuated free reeds tuned to notes of a musical scale and controlled by means of a keyboard. The family is divided into two preliminary halves: “Diatonic” accordions, that play different pitches when bellows are expanded or compressed and “Chromatic” accordions, that sound the same pitch in both bellows directions. -

The Source Spectrum of Double-Reed Wood-Wind Instruments

Dept. for Speech, Music and Hearing Quarterly Progress and Status Report The source spectrum of double-reed wood-wind instruments Fransson, F. journal: STL-QPSR volume: 8 number: 1 year: 1967 pages: 025-027 http://www.speech.kth.se/qpsr MUSICAL ACOUSTICS A. THE SOURCE SPECTRUM OF DOUBLE-REED WOOD-VIIND INSTRUMENTS F. Fransson Part 2. The Oboe and the Cor Anglais A synthetic source spectrum for the bassoon was derived in part 1 of the present work (STL-GPSR 4/1966, pp. 35-37). A synthesis of the source spectrum for two other representative members of the double-reed family is now attempted. Two oboes of different bores and one cor anglais were used in this experiment. Oboe No. 1 of the old system without marking, manufactured in Germany, has 13 keys; Oboe No. 2, manufactured in France and marked Gabart, is of the modern system; and the Cor Anglais No. 3 is of the old system with 13 keys and made by Bolland & Wienz in Hannover. Measurements A mean spectrogram for tones within one octave covering a frequen- cy range from 294 to 588 c/s was produced for the oboes by playing two scrics of tones. One serie was d4, e4, f4, g4, and a and the other 4 serie was g 4, a4, b4, c 5' and d5. Both series were blown slurred ascending and descending in rapid succession, recorded and combined to a rather inharmonic duet on one loop. The spectrograms are shown in Fig. 111-A- 1 whcre No. 1 displays the spectrogram for the old sys- tem German oboe and No. -

Woodwind Family

Woodwind Family What makes an instrument part of the Woodwind Family? • Woodwind instruments are instruments that make sound by blowing air over: • open hole • internal hole • single reeds • double reed • free reeds Some woodwind instruments that have open and internal holes: • Bansuri • Daegeum • Fife • Flute • Hun • Koudi • Native American Flute • Ocarina • Panpipes • Piccolo • Recorder • Xun Some woodwind instruments that have: single reeds free reeds • Clarinet • Hornpipe • Accordion • Octavin • Pibgorn • Harmonica • Saxophone • Zhaleika • Khene • Sho Some woodwind instruments that have double reeds: • Bagpipes • Bassoon • Contrabassoon • Crumhorn • English Horn • Oboe • Piri • Rhaita • Sarrusaphone • Shawm • Taepyeongso • Tromboon • Zurla Assignment: Watch: Mr. Gendreau’s woodwind lesson How a flute is made How bagpipes are made How a bassoon reed is made *Find materials in your house that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) can use to make a woodwind (i.e. water bottle, straw and cup of water, piece of paper, etc). *Find some other materials that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) you can make a different woodwind instrument. *What can you do to change the sound of each? *How does the length of the straw effect the sound it makes? *How does the amount of water effect the sound? When you’re done, click here for your “ticket out the door”. Some optional videos for fun: • Young woman plays music from “Mario” on the Sho • Young boy on saxophone • 9 year old girl plays the flute.