Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mijn Tegenstem Gedichten 1966-1973 Hugues C. Pernath

Mijn tegenstem Gedichten 1966-1973 Hugues C. Pernath bron Hugues C. Pernath, Mijn tegenstem. Gedichten 1966-1973. Pink Editions & Productions, Antwerpen 1975 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/pern001mijn02_01/colofon.htm © 2004 dbnl / erven Hugues C. Pernath 4 La morale c'est toujours la morale des autres Leo Ferré Hugues C. Pernath, Mijn tegenstem 5 Vijftig index-gedichten 1966-1970 Hugues C. Pernath, Mijn tegenstem 7 1 Dit is geen schande, ofschoon Sinds vorige tijden De uitersten werden aangegeven. Tot de laatste bittere jaren toe. Ongetwijfeld, De mooie letteren bloeien De voortreffelijke ouders, de woorden Nooit ondraaglijk Noch onder elkaar, noch onder het volk. Ik zal slechts zien wat ik zie Wat aanwezig is en weer huiswaarts keert. Hugues C. Pernath, Mijn tegenstem 8 2 Zo sta ik buiten de gedachte Met dit besluit Dat bij mijn leeftijd past En onderga, nauwelijks Na een jaar opnieuw Iemand die niet alles achterliet. Ik neem haar in dezelfde kleur En verdeel de vreugde van mijn vreugde Haar leven dat zij leeft, haar geloof in mij En mijn geloof in haar. En nooit uit de twijfel Nooit uit de liefde, nooit Maakte het leven zulk begin. Hugues C. Pernath, Mijn tegenstem 9 3 Vertraagd, de geduchte daden Zich tevreden stellend met de overeenkomst. Zo was het, Mijn misdaad is mij te machtig geworden Mijn liefde werd mijn liefde. Dezelfde manier van leven zag het leven Begreep en onderging Een waardigheid Waarbij ik te kort schoot. En in deze late, eindelijke rust Deze moeite, herken ik haar. Zij, de vrouw die overweldigde Die zo gehandeld heeft. -

Nederlandstalige Liedjes Abel Onderweg Acda En De Munnik Het

Nederlandstalige liedjes Abel Onderweg Acda en de Munnik Het regent zonnestralen Acda en de Munnik Als het vuur gedoofd is Acda en de Munnik Slaap zacht Elisabeth Alderliefse/Shaffy Vivre/Laat me André Hazes De Vlieger André Hazes Een beetje verliefd André Hazes Het laatste rondje André Hazes jr Leef Anneke Grönloh Brandend zand Anton Beuving Ketelbinkie Armand Ben ik te min? Arne Jansen Meisjes met rode haren Ben Cramer Hij was maar een clown Benny Neyman Een vrijgezel Benny Neyman Ode aan Maastricht Benny Neyman Waarom fluister ik je naam nog? Bloem Even aan mijn moeder vragen Blof Dansen aan zee Blof De Zeeuwse kust Blof Zoutelande Bots Zeven dagen lang Boudewijn de Groot Alles wordt gewoon Boudewijn de Groot Als jij niet van me houdt Boudewijn de Groot Avond Boudewijn de Groot Beneden alle peil Boudewijn de Groot De dominee van Amersfoort Boudewijn de Groot De Noordzee Boudewijn de Groot De verbouwing Boudewijn de Groot De vondeling van Ameland Boudewijn de Groot Kindertijd Boudewijn de Groot Land van Maas en Waal Boudewijn de Groot Meisje van 16 Boudewijn de Groot Meneer de president Boudewijn de Groot Naast jou Boudewijn de Groot Strand Boudewijn de Groot Tante Julia Boudewijn de Groot Telkens weer Boudewijn de Groot Testament Boudewijn de Groot Verdronken vlinder Boudewijn de Groot Vertrek Boudewijn de Groot Wie ik ben Bram Vermeulen Een wedstrijd Ciske de Rat Zo verdomd alleen Claudia de Breij Mag ik dan bij jou? Connie van den Bosch Een roosje mijn roosje Connie van den Bosch Sjakie van de hoek Cornelis Vreeswijk De nozem en de -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Omroep Brabant A+B Rotatie Printed on 30-1-2012 10:12

Omroep Brabant A+B Rotatie Printed on 30-1-2012 10:12 Artist Title Year 10 CC Donna 1973 10 CC Dreadlock holiday 1978 10 CC Feel the love 1983 10 CC Food for thought 1983 10 CC Good morning judge 1977 10 CC I'm Mandy fly me 1975 10 CC I'm not in love 1975 10 CC The things we do for love 1976 10 CC The Wall Street shuffle 1974 16 Down Subtle movements 2002 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon says 1968 2 Belgen Lena 1985 2 Unlimited Nothing like the rain 1995 3 Doors Down Here without you 2004 3 J's Bevlogen als vogels 2009 3 J's De stroom 2011 3 J's De weg 2012 3 J's Geloven in het leven 2010 3 J's Hou van mij 2008 3 J's Je vecht nooit alleen 2011 3 J's Kamers van m'n hart 2009 3 J's Kom 2008 3 J's Laatste dag (live) 2009 3 J's Loop met me over zee 2010 3 J's Net alsof 3 J's Toen ik jou vergat 2011 3 J's Vandaag ben ik vrij 2009 3 J's Watermensen 2008 3 J's/Ellen ten Damme Wat is dromen 2010 3T Anything 1996 3T Stuck on you 2004 4 Hero Les fleurs 2001 4 Non Blonds What's up 1993 5000 Volts I'm on fire 1975 77 Bombay street Long way 2012 8 Ball Boppers Huus stut te schudde 98 Degrees/Stevie Wonder True to your heart 1998 A Balladeer Swim with Sam 2006 A Flock Of Seagulls The more you live the more you love 1984 A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I had a photograph of you) 1982 Aaron Neville/Linda Rondstadt Don't know much 1989 Abba Chiquitita 1979 Abba Dancing queen 1976 Abba Does your mother know 1979 Omroep Brabant A+B Rotatie Page 2 Artist Title Year Abba Eagle 1978 Abba Fernando 1976 Abba Gimme! gimme! gimme! (a man after m.. -

TRACKLIST KARAOKE NEDERLANDS 1 Blof Open Je Ogen Blof Hier Blof Zo Stil Blof & Nielson Mannenharten Blof & Sabrina Starke Meer Kan Het Niet Zijn Bonnie St

3JS Wiegelied 3JS Kom 3JS (Eurovision 2011) Je vecht nooit alleen Abel Onderweg Acda En De Munnik Het regent zonnestralen Acda En De Munnik Niet of nooit geweest Acda En De Munnik Cd van jou cd van mij Acda En De Munnik De stad Amsterdam Alderliefste & Ramses Shaffy & Liesbeth List Laat Me / Vivre Alpenzusjes Naar Voren, Naar Achter André Hazes Zij gelooft in mij André Hazes De Vlieger André Hazes Bloed, zweet en tranen André Hazes Een beetje verliefd André Hazes Ik leef m'n eigen leven André Hazes Uit m'n bol André Hazes Waarom André Hazes Ik meen 't André Hazes Wat is dan liefde André Hazes Hoogste tijd André Hazes Dat ene moment André Hazes Eenzaam zonder jou André Hazes Als je alles weet André Hazes Wij houden van Oranje André Hazes Ik heb de zomer in m'n bol André Hazes Diep in mijn hart André Hazes Jr. Leef André Hazes Jr. Wat is de waarheid André Hazes Jr. Niet voor lief André van Duin Als de zon schijnt Angela Groothuizen De helft van mij Anouk Dominique Antonie Kamerling (Hero) Toen Ik Je Zag Arjon feat. DJ Nelis Schudden Arjon feat. DJ Willem de Wijs & Feest DJ Bas Zakka zakka Armand Ben Ik Te Min Arne Jansen Meisjes met rode haren Artist Title Astrid Nijgh Ik doe wat ik doe Ben Cramer De clown Benny Neyman Vrijgezel Berget Lewis Zwart wit Blof Wat Zou Je Doen? Blof Liefs uit Londen Blof Omarm Me Blof Alles is liefde Blof Alles is liefde (akoestisch) TRACKLIST KARAOKE NEDERLANDS 1 Blof Open je ogen Blof Hier Blof Zo stil Blof & Nielson Mannenharten Blof & Sabrina Starke Meer kan het niet zijn Bonnie St. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

Repertoirelijst “Het Juffertje” Staat Uw Lievelingsliedje Er Niet Bij? Laat Het Me Weten En Ik Zorg Ervoor Dat Het Op Het Orgel Gearrangeerd Wordt!

Repertoirelijst “Het Juffertje” Staat uw lievelingsliedje er niet bij? Laat het me weten Www.draaiorgel.nl en ik zorg ervoor dat het op het orgel gearrangeerd wordt! Titel Categorie A.B.C. Boogie - Bill Haley and His Comets Boogie Woogie Be my boogiewoogie baby Boogie Woogie Bill Haley - Rock en Roll (medley) Boogie Woogie Brenda Boogie Boogie Woogie Chicken Reel Boogie Woogie China Boogie Boogie Woogie Cuckoo Boogie Boogie Woogie Music Boogie Boogie Woogie Paris Boogie Boogie Woogie Rock en Roll Fever Boogie Woogie Rock en Roll Fever 2 Boogie Woogie Sint Jobs Boogie Boogie Woogie Telephone Baby Boogie Woogie Trappelzak Boogie Boogie Woogie Tutti Frutti Boogie Woogie Twee bruine ogen Boogie Woogie Twistziek Boogie Woogie Wanty Boogie Boogie Woogie Titel Categorie A Mighty Fortress Christelijke muziek Abide with me Christelijke muziek Amazing Grace Christelijke muziek As the deer panteth for the water Christelijke muziek Ave Maria Christelijke muziek Blessed bie the tie that binds Christelijke muziek Een toekomst vol van hoop – Sela Christelijke muziek Great is thy Faithfulness Christelijke muziek Heer u bent de grond waarop ik sta Christelijke muziek How firm a Foundation Christelijke muziek I need the every hour Christelijke muziek Ik zal er zijn - Sela Christelijke muziek Jezus loves me Christelijke muziek Lof zij de her de almachtige koning der ere Christelijke muziek May God's Blessing Christelijke muziek My Jezus I love Thee Christelijke muziek Nearer my God to thee Christelijke muziek O for a thousand tongues to sing Christelijke -

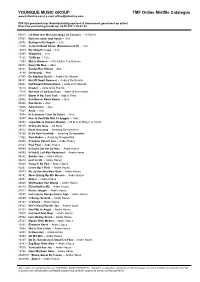

YMG/TMF Online MIDI Catalogue Sorted on Songtitle

YOUNIQUE MUSIC GROUP TMF Online Midifile Catalogus www.tmfonline.com | e-mail: [email protected] PDF lijst gesorteerd op: Nederlandstalig pop/rock & Amusement gesorteerd op artiest Real time overzicht gemaakt op: 28-09-2021 / 09:41:20 99015 Lik Maar Aan Me Lolly (Sopa De Caracol) - 10 Dance 27061 Kom (en neem mijn hand) - 3J's 29076 Bevlogen Als Vogels - 3J's 11035 Je Vecht Nooit Alleen (Eurovision 2011) - 3J's 12079 Bij Hoog En Laag - 3J's 13093 Wiegelied - 3J's 13122 Til Me op - 3J's 11093 Wat Is Dromen - 3J's & Ellen Ten Damme 20071 Neem Me Mee - Abel 20151 Zonder Een Woord - Abel 18139 Onderweg - Abel 21049 De Kapitein Deel II - Acda & De Munnik 98151 Niet Of Nooit Geweest - Acda & De Munnik 28041 Het Regent Zonnestralen - Acda & De Munnik 13113 Draaien - Acda & De Munnik 17016 Wat Heb Je Gedaan Daan - Adele Bloemendaal 26017 Boom Is Ho, Tuut Tuut - Adje & Theo 20052 Een Bossie Rooie Rozen - Alex 22022 Kee Seraa - Alex 16066 Adio Amore - Alex 17027 Anita - Alex 18094 Ik Schreeuw 't Van De Daken - Alex 19077 Nee Je Hoeft Me Niet Te Zeggen - Alex 25053 Leipe Mocro Flavour (Remix) - Ali B. feat. Brayce & Yes-R 99135 Groen Als Gras - All Stars 28012 Oude Maasweg - Amazing Stroopwafels 28100 Ik Ga Naar Frankrijk - Amazing Stroopwafels 11062 Ome Kobus - Amazing Stroopwafels 20080 Eenzaam Zonder Jou - Andre Hazes 21163 Poei Poei - Andre Hazes 94049 Ik Dacht Dat Het Uit Was - Andre Hazes 94093 Ik Heb U Lief Mijn Nederland - Andre Hazes 94142 Zonder Jou - Andre Hazes 94218 Leef Je Uit - Andre Hazes 95088 Terug In De Tijd - Andre Hazes 95207 -

Het Temmen Van De Feeks

Het temmen van de feeks William Shakespeare 1589 (volgens Brian Morris, inleiding bij Arden-uitgave) Vertaling Ruud Wessels 2011 © deze vertaling Ruud Wessels 2011 Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt worden door middel van druk, fotocopie, microfilm of op welke wijze dan ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de auteur, Ruud Wessels, te bereiken via [email protected] Toneelgroepen die deze tekst willen opvoeren, dienen hiervoor toestemming te verkrijgen van de auteur en met hem overeenkomst te sluiten over een auteursrechtelijke vergoeding. De auteur is bereikbaar via [email protected]. Leperd (Sly) Waardin Heer Dienaar 1 Dienaar 2 (Spelers) Lucentio Tranio Baptista Gremio Katherina Hortensio Bianca Petruchio Grumio Biondello Curtis Leraar Marskramer Kleermaker Vincentio Politieman Weduwe 1 Deze tekst is auteursrechtelijk beschermd en mag niet worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van fotokopie, scan of welke wijze dan ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de rechthebbende. Neem contact op met de auteur als u deze tekst wilt gebruiken. © Ruud Wessels [email protected] gedownload op 2 oktober 2021 INDUCTIE SCENE 1 (Waardin smijt Leperd op straat) LEPERD Ik sla je op je sodemieter, godsamme! WAARDIN Aan de schandpaal met jou! Schoft! LEPERD Nee, slet! De Leperds zijn geen schofte! Kijk maar na, wij kwamen binne met Filips de Zwijger. ‘k Maak ’r dus geen woorde meer aan vuil. De wereld gaat naar de ratsmodee. Sessa! WAARDIN Je wil nie betale voor de glaze die je heb gebroke? LEPERD Geen stuiver. Gaat weg, scheer je heen mens, ga toch naar je kouwe nest en verwarm jezelf. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/11/2017 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/11/2017 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Shape of You - Ed Sheeran Someone Like You - Adele Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Piano Man - Billy Joel At Last - Etta James Don't Stop Believing - Journey Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Wannabe - Spice Girls Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Jackson - Johnny Cash Free Fallin' - Tom Petty Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Look What You Made Me Do - Taylor Swift I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Body Like a Back Road - Sam Hunt Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Santeria - Sublime Summer Nights - Grease Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Turn The Page - Bob Seger Zombie - The Cranberries Crazy - Patsy Cline Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Kryptonite - 3 Doors Down My Girl - The Temptations Despacito (Remix) - Luis Fonsi Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Let It Go - Idina Menzel Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Monster Mash - Bobby Boris Pickett Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's My Way - Frank Sinatra In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Rolling In The Deep - Adele All Of Me - John Legend These -

Bjeno Songs of Love (Teksten)

Bjeno Songs of Love (teksten) Versie 13-10-2018 ( 44 songs) Inleiding Wat is Bjeno Songs of Love? Bjeno Songs of Love is de werktitel van een nieuw ritueel / persoonlijke uitdaging: "Het dagelijks schrijven van een lied over de liefde (of iets anders dat je hart raakt.)" In het onderstaande document vind je de bijbehorende teksten. In het schrijven van liedjes heb ik altijd een diepere laag en energie ontdekt of weten los te maken. In mijzelf, maar ook in anderen. Door daar nu dagelijks mee bezig te zijn raak ik in de flow van (en focus op) de mooie, diepe en intense dingen van het leven. Op 13 oktober 2018 stond de teller op 44. Zelf teksten nodig? Mocht je zelf muzikant zijn en mijn teksten willen gebruiken voor je eigen muziek: voel je vrij, maar stuur me wel even het resultaat [email protected]. Ik ben benieuwd wat jij kunt maken met mijn teksten. Uiteraard blijf ik eigenaar van de teksen. Indien gewenst kan ik ook teksten schrijven op bestelling. Inhoud Inleiding ................................................................................................................................................... 2 A moment ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Again (She went out) ............................................................................................................................... 6 Butterfly .................................................................................................................................................. -

Boris Joechananov Dmitri Koerljandski Stanislavsky Electrotheatre

BORIS JOECHANANOV DMITRI KOERLJANDSKI STANISLAVSKY ELECTROTHEATRE INHOUD CONTENT INFO & CREDITS 02 TIRANNIE ZONDER GEZICHT 04 A FACELESS TYRANNY 07 OVER DE ARTIESTEN 12 ABOUT THE ARTISTS 15 LIBRETTO 17 FOCUS: DEMOCRATIE 32 FOCUS: DEMOCRACY 32 HOLLAND FESTIVAL 2017 36 WORD VRIEND JOIN US 38 COLOFON COLOPHON 40 1 INFO CREDITS DO 15.6, VR 16.6 concept, conceptuele uitwerking THU 15.6, FRI 16.6 concept, conceptual elaboration Boris Joechananov, Sergej Adonjev aanvang starting time 20:30 muziek music 8.30 pm Dmitri Koerljandski locatie venue libretto libretto Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ Boris Joechananov, Dmitri Koerljandski duur running time regie direction 1 uur 30 minuten, geen pauze Boris Joechananov 1 hour 30 minutes, no interval decor set design taal language Stepan Loekjanov Russisch met Nederlandse en Engelse boventiteling kostuums costume Russian with Dutch and English surtitles Anastasia Nefedova inleiding introduction choreografie choreography door by René van Peer Andrej Koeznetsov-Vetsjeslov do 15.6, vr 16.6 – 19.45 Thu 15.6, Fri 16.6 – 7.45 pm geluid sound Oleg Makarov meet the artist met with Boris Joechananov, Sergej licht light Adonjev, Dmitri Koerljandski Sergej Vasiliev vr 16.6 – na de voorstelling Fri 16.6 – after the performance koordirigent choirmaster Dmitri Matvienko rollen characters Nero – Sergej Malinin, tenor tenor Seneca – Alexej Kochanov, bariton baritone Geest van Agrippina Ghost of Agrippina – Arina Zvereva, mezzosopraan mezzo soprano Prefect – Vasili Korostelev, bas bass Trotski – Joeri Doevanov, acteur actor 2 Octavia