Best Practices in Fair Use of Dance-Related Materials Recommendations for Librarians, Archivists, Curators, and Other Collections Staff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 12 – 16, 2016

February 12 – 16, 2016 danceFilms.org | Filmlinc.org ta b l e o F CONTENTS DA N C E O N CAMERA F E S T I VA L Inaugurated in 1971, and co-presented with Dance Films Association and the Film Society of Lincoln Center since 1996 (now celebrating the 20th anniversary of this esteemed partnership), the annual festival is the most anticipated and widely attended dance film event in New York City. Each year artists, filmmakers and hundreds of film lovers come together to experience the latest in groundbreaking, thought-provoking, and mesmerizing cinema. This year’s festival celebrates everything from ballet and contemporary dance to the high-flying world of trapeze. ta b l e o F CONTENTS about dance Films association 4 Welcome 6 about dance on camera Festival 8 dance in Focus aWards 11 g a l l e ry e x h i b i t 13 Free events 14 special events 16 opening and closing programs 18 main slate 20 Full schedule 26 s h o r t s p r o g r a m s 32 cover: Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers in Kinetic Molpai, ca. 1935 courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance festival archives this Page: The Dance Goodbye ron steinman back cover: Feelings are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer courtesy estate of warner JePson ABOUT DANCE dance Films association dance Films association and dance on camera board oF directors Festival staFF Greg Vander Veer Nancy Allison Donna Rubin Interim Executive Director President Virginia Brooks Liz Wolff Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Paul Galando Brian Cummings Joanna Ney Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Vice President and Chair of Ron -

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

Shot and Captured Turf Dance, YAK Films, and the Oakland, California, R.I.P

Shot and Captured Turf Dance, YAK Films, and the Oakland, California, R.I.P. Project Naomi Bragin When a group comprised primarily of African-derived “people” — yes, the scare quotes matter — gather at the intersection of performance and subjectivity, the result is often [...] a palpable structure of feeling, a shared sense that violence and captivity are the grammar and ghosts of our every gesture. — Frank B. Wilderson, III (2009:119) barred gates hem sidewalk rain splash up on passing cars unremarkable two hooded figures stand by everyday grays wash street corner clean sweeps a cross signal tag white R.I.P. Haunt They haltingly disappear and reappear.1 The camera’s jump cut pushes them abruptly in and out of place. Cut. Patrol car marked with Oakland Police insignia momentarily blocks them from view. One pulls a 1. Turf Feinz dancers appearing in RIP RichD (in order of solos) are Garion “No Noize” Morgan, Leon “Mann” Williams, Byron “T7” Sanders, and Darrell “D-Real” Armstead. Dancers and Turf Feinz appearing in other TDR: The Drama Review 58:2 (T222) Summer 2014. ©2014 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 99 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/DRAM_a_00349 by guest on 01 October 2021 keffiyah down revealing brown. Skin. Cut. Patrol car turns corner, leaving two bodies lingering amidst distended strains of synthesizer chords. Swelling soundtrack. Close focus in on two street signs marking crossroads. Pan back down on two bodies. Identified. MacArthur and 90th. Swollen chords. In time to the drumbeat’s pickup, one ritually crosses himself. -

2021-02-12 FY2021 Grant List by Region.Xlsx

New York State Council on the Arts ‐ FY2021 New Grant Awards Region Grantee Base County Program Category Project Title Grant Amount Western New African Cultural Center of Special Arts Erie General Support General $49,500 York Buffalo, Inc. Services Western New Experimental Project Residency: Alfred University Allegany Visual Arts Workspace $15,000 York Visual Arts Western New Alleyway Theatre, Inc. Erie Theatre General Support General Operating Support $8,000 York Western New Special Arts Instruction and Art Studio of WNY, Inc. Erie Jump Start $13,000 York Services Training Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie General Support ASI General Operating Support $49,500 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie Regrants ASI SLP Decentralization $175,000 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Buffalo and Erie County Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Historical Society Western New Buffalo Arts and Technology Community‐Based BCAT Youth Arts Summer Program Erie Arts Education $10,000 York Center Inc. Learning 2021 Western New BUFFALO INNER CITY BALLET Special Arts Erie General Support SAS $20,000 York CO Services Western New BUFFALO INTERNATIONAL Electronic Media & Film Festivals and Erie Buffalo International Film Festival $12,000 York FILM FESTIVAL, INC. Film Screenings Western New Buffalo Opera Unlimited Inc Erie Music Project Support 2021 Season $15,000 York Western New Buffalo Society of Natural Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Sciences Western New Burchfield Penney Art Center Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $35,000 York Western New Camerta di Sant'Antonio Chamber Camerata Buffalo, Inc. -

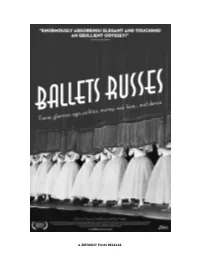

Ballets Russes Press

A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE THEY CAME. THEY DANCED. OUR WORLD WAS NEVER THE SAME. BALLETS RUSSES a film by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller Unearthing a treasure trove of archival footage, filmmakers Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine have fashioned a dazzlingly entrancing ode to the rev- olutionary twentieth-century dance troupe known as the Ballets Russes. What began as a group of Russian refugees who never danced in Russia became not one but two rival dance troupes who fought the infamous “ballet battles” that consumed London society before World War II. BALLETS RUSSES maps the company’s Diaghilev-era beginnings in turn- of-the-century Paris—when artists such as Nijinsky, Balanchine, Picasso, Miró, Matisse, and Stravinsky united in an unparalleled collaboration—to its halcyon days of the 1930s and ’40s, when the Ballets Russes toured America, astonishing audiences schooled in vaudeville with artistry never before seen, to its demise in the 1950s and ’60s when rising costs, rock- eting egos, outside competition, and internal mismanagement ultimately brought this revered company to its knees. Directed with consummate invention and infused with juicy anecdotal interviews from many of the company’s glamorous stars, BALLETS RUSSES treats modern audiences to a rare glimpse of the singularly remarkable merger of Russian, American, European, and Latin American dancers, choreographers, composers, and designers that transformed the face of ballet for generations to come. — Sundance Film Festival 2005 FILMMAKERS’ STATEMENT AND PRODUCTION NOTES In January 2000, our Co-Producers, Robert Hawk and Douglas Blair Turnbaugh, came to us with the idea of filming what they described as a once-in-a-lifetime event. -

Walking Distance Dance Festival

Walking Distance Dance Festival May 15 - 20, 2018 Photo by Darren Phillip Hoffman Darren by Photo ABOUT ODC THEATER MISSION AND IMPACT: ODC Theater exists to empower and develop innovative artists. It participates in the creation of new works through commissioning, presenting, mentorship and space access; it develops informed, engaged and committed audiences; and advocates for the performing arts as an essential component to the economic and cultural development of our community. The Theater is the site of over 150 performances a year involving nearly 1,000 local, regional, national and international artists. Since 1976, ODC Theater has been the mobilizing force behind countless San Francisco artists and the foothold for national and international touring artists seeking debut in the Bay Area. Our Theater, founded by Brenda Way and currently under the direction of Julie Potter, has earned its place as a cultural incubator by dedicating itself to creative change-makers, those leaders who give our region its unmistakable definition and flare. Nationally known artists Spaulding Gray, Diamanda Galas, Molissa Fenley, Bill T. Jones, Eiko & Koma, Ronald K. Brown/EVIDENCE, Ban Rarra and Karole Armitage are among those whose first San Francisco appearance occurred at ODC Theater. ODC Theater is part of a two-building campus dedicated to supporting every stage of the artistic lifecycle-conceptualization, creation, and performance. This includes our flagship company, ODC/ Dance, and our School, in partnership with Rhythm and Motion Dance Workout down the street at 351 Shotwell. More than 200 classes are offered weekly and your first adult class is $5. For more information on ODC Theater and all its programs please visit: www.odc.dance SUPPORT: ODC Theater is supported in part by the following foundations and agencies: Grants for the Arts/San Francisco Hotel Tax Fund, Anonymous Foundation Partner, New England Foundation for the Arts / National Dance Project, The Koret Foundation, Andrew W. -

Authorship, Ownership , and Control: Balancing the Economicc and Artistic Issues Raised by the Martha Graham Copyright Case

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 15 Volume XV Number 3 Volume XV Book 3 Article 5 2005 Authorship, Ownership , and Control: Balancing the Economicc and Artistic Issues Raised by the Martha Graham Copyright Case Sharon Connelly Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Sharon Connelly, Authorship, Ownership , and Control: Balancing the Economicc and Artistic Issues Raised by the Martha Graham Copyright Case, 15 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 837 (2005). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol15/iss3/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authorship, Ownership , and Control: Balancing the Economicc and Artistic Issues Raised by the Martha Graham Copyright Case Cover Page Footnote Hugh Hansen, Stanley Rothenberg, and Linda Sugin; Barbara Quint, Assistant Attorney General, Charities Bureau, New York State Department of Law; Nicole Serratore; Craig Flanagin; Sarah Adams; and Elizabeth Hoag This note is available in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol15/iss3/5 CONNELLY 4/30/2005 2:05 PM Authorship, Ownership, and Control: Balancing the Economic and Artistic Issues Raised by the Martha Graham Copyright Case Sharon Connelly* We have all walked the high wire of circumstance at times. -

B-Girl Like a B-Boy Marginalization of Women in Hip-Hop Dance a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of H

B-GIRL LIKE A B-BOY MARGINALIZATION OF WOMEN IN HIP-HOP DANCE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN DANCE DECEMBER 2014 By Jenny Sky Fung Thesis Committee: Kara Miller, Chairperson Gregg Lizenbery Judy Van Zile ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give a big thanks to Jacquelyn Chappel, Desiree Seguritan, and Jill Dahlman for contributing their time and energy in helping me to edit my thesis. I’d also like to give a big mahalo to my thesis committee: Gregg Lizenbery, Judy Van Zile, and Kara Miller for all their help, support, and patience in pushing me to complete this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………… 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 1 2. Literature Review………………………………………………………………… 6 3. Methodology……………………………………………………………………… 20 4. 4.1. Background History…………………………………………………………. 24 4.2. Tracing Female Dancers in Literature and Film……………………………... 37 4.3. Some History and Her-story About Hip-Hop Dance “Back in the Day”......... 42 4.4. Tracing Females Dancers in New York City………………………………... 49 4.5. B-Girl Like a B-Boy: What Makes Breaking Masculine and Male Dominant?....................................................................................................... 53 4.6. Generation 2000: The B-Boys, B-Girls, and Urban Street Dancers of Today………………...……………………………………………………… 59 5. Issues Women Experience…………………………………………………….… 66 5.1 The Physical Aspect of Breaking………………………………………….… 66 5.2. Women and the Cipher……………………………………………………… 73 5.3. The Token B-Girl…………………………………………………………… 80 6.1. Tackling Marginalization………………………………………………………… 86 6.2. Acknowledging Discrimination…………………………………………….. 86 6.3. Speaking Out and Establishing Presence…………………………………… 90 6.4. Working Around a Man’s World…………………………………………… 93 6.5. -

Retlof Organization Exempt Froiicome

Form 9 9 0 RetLof Organization Exempt Froiicome Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung Department of the Treasury benefit trust or private foundation) Internal Revenue Service ► The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. A i-or ine zuu4 calenaar ear or tax year De mnm u i i Luna anu enam ub ju Zuu5 B Check If epppeahle please C Name of organization D Employer identification number Address -Iris Chong. JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND 23-7174183 label or Name change print or Number and street (or P.O box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial retun typ e. See Final return Specific 575 MADISON AVENUE 703 (212)752-8277 Amended Inj„` rehcn City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 "n:ma.'° Cash X Accrual Bono. O Apndl,plon NY 1 0022 1 Otherspectfy) 10, • Section 501 ( c)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable H and I a re not applicable to section 527 organizations trusts must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? ❑ Yes a No G Website: ► W . JEWISHCOMMUNALFUND . ORG H(b) If "Yes," enter number of affiliates IN, J Organization type (check only one) ► X 501(c) (03 ) A (Insert no) 4947(a)(1) or 527 H(c) A. all affiliates included? Yes �No (If "No," attach a list See instnichons K Check here ► it the organization' s gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 The H(d) Is this a separate return filed by an organizati on need not file a retu rn with the IRS, but if the organization received a Form 990 Package organization covered by e group ruling ? Yes X No in the ma il, it should file a return without financial data Some states requi re a complete retu rn. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Current and Future

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Current and Future Role of Screendance Curation THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS in Dance by Boroka Krisztina Nagy Thesis Committee: Associate Professor John Crawford, Chair Professor Lisa Naugle Professor Alan Terricciano 2015 © 2015 Boroka Krisztina Nagy TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS iv INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Overview of Screendance and Curatorial Practice 3 CHAPTER 2: Survey of Current Screendance Festivals 13 CHAPTER 3: Practices of Current Practitioners 22 CHAPTER 4: Screendance and Interactive Performance: Presentation and Curation 27 CHAPTER 5: Conclusion 32 REFERENCES 36 APPENDIX A: Additional Bibliography 40 APPENDIX B: List of Festivals in the United States that Show Screendance 42 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my Thesis Chair, John Crawford, for his patience, advice, and openness with this research. All that I have learned from him in these past two years has informed and made my thesis work possible. I am thankful for his intellectual, artistic, and technical guidance. I appreciate his passion for the partnership of technology and dance. I am grateful for Lisa Naugle and Alan Terricciano for the inspiring and idea-sparking conversations that helped move this thesis forward. Many thanks for believing in my ideas. Their mentorship and enthusiasm for the arts has influenced my artistry and research. My express my appreciation to Douglas Rosenberg, Martha Curtis, and Greta Schoenberg. I am thankful for the time they took to share with me their knowledge and experience with the ever-evolving field of screendance. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE The Film Society of Lincoln Center and Dance Films Association announce the 41st edition of DANCE ON CAMERA February 1-5, 2013 Opening Night launches with the World Premiere of Alan Brown’s FIVE DANCES th Lineup highlights include the 50 Anniversary of Francisco Rovira Beleta’s flamenco classic, LOS TARANTOS; ice dancing with Olympic legend Dick Button, and a salute to pioneer dance filmmaker Shirley Clarke "A Dance of Light: Forty-Years of Self-Portraits by Arno Rafael Minkkinen," photography exhibit will be on display New York, NY, December 5, 2012 – The Film Society of Lincoln Center and Dance Films Association today announced the lineup for the 41st edition of Dance on Camera. Taking place February 1-5, the dance-centric film festival returns to the Film Society for the 17th consecutive year with an exciting and diverse array of dance films, including several premieres. This year’s selections range widely in subject and genre beginning with the Opening Night presentation of Alan Brown’s youthful, sexy contemporary coming of age film, FIVE DANCES, with stunning choreography by Jonah Bokaer. Closing Night honors will be shared by Sylvie Collier’s charming documentary TO DANCE LIKE A MAN, featuring the first known Cuban identical boy triplets - 11-year-old students at the National Ballet School in Havana, and Andrew Garrison’s TRASH DANCE inventive choreographed “dance” of Austin, Texas garbage collectors. "Dance on Camera is an exuberant hybrid. Its roots hold the seeds of innovation inherent in the concept of combining dance with cinematography in ways that alter one’s perception of both mediums," said Joanna Ney, co-curator of the Dance on Camera Festival. -

Mechanical Ball Set to Chamber Music

Mechanical ball set to chamber music Production 2014 | 60 min Show suitable for all audiences, 6 years old and above © Thomas© Bohl A word from the choreographer .................................................................................................... 2 Choreographer: Anne Nguyen ...................................................................................................... 4 Cast ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Press extracts.............................................................................................................................. 8 Looping pop ball with audience participation ............................................................................... 10 Workshops and shared events based on bal.exe ........................................................................... 10 Partners.................................................................................................................................... 11 Booking information .................................................................................................................. 11 par Terre / Anne Nguyen Dance Company Correspondence adress: 113 rue Saint-Maur – 75011 PARIS Registered office: Bat. D – 74 Avenue Laferrière - 94000 CRETEIL SIRET: 484 553 391 00042- APE: 9001Z - Licence entrepreneur de spectacles: 2-1066967 Tel. + 33 (0)6 15 59 82 28 – [email protected] - www.compagnieparterre.com bal.exe