Cinematography and Choreography: "It Takes Two to Tango"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

How do I look? Viewing, embodiment, performance, showgirls, and art practice. CARR, Alison J. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. How Do I Look? Viewing, Embodiment, Performance, Showgirls, & Art Practice Alison Jane Carr A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ProQuest Number: 10694307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I, Alison J Carr, declare that the enclosed submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and consisting of a written thesis and a DVD booklet, meets the regulations stated in the handbook for the mode of submission selected and approved by the Research Degrees Sub-Committee of Sheffield Hallam University. -

February 12 – 16, 2016

February 12 – 16, 2016 danceFilms.org | Filmlinc.org ta b l e o F CONTENTS DA N C E O N CAMERA F E S T I VA L Inaugurated in 1971, and co-presented with Dance Films Association and the Film Society of Lincoln Center since 1996 (now celebrating the 20th anniversary of this esteemed partnership), the annual festival is the most anticipated and widely attended dance film event in New York City. Each year artists, filmmakers and hundreds of film lovers come together to experience the latest in groundbreaking, thought-provoking, and mesmerizing cinema. This year’s festival celebrates everything from ballet and contemporary dance to the high-flying world of trapeze. ta b l e o F CONTENTS about dance Films association 4 Welcome 6 about dance on camera Festival 8 dance in Focus aWards 11 g a l l e ry e x h i b i t 13 Free events 14 special events 16 opening and closing programs 18 main slate 20 Full schedule 26 s h o r t s p r o g r a m s 32 cover: Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers in Kinetic Molpai, ca. 1935 courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance festival archives this Page: The Dance Goodbye ron steinman back cover: Feelings are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer courtesy estate of warner JePson ABOUT DANCE dance Films association dance Films association and dance on camera board oF directors Festival staFF Greg Vander Veer Nancy Allison Donna Rubin Interim Executive Director President Virginia Brooks Liz Wolff Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Paul Galando Brian Cummings Joanna Ney Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Vice President and Chair of Ron -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

10 Tips on How to Master the Cinematic Tools And

10 TIPS ON HOW TO MASTER THE CINEMATIC TOOLS AND ENHANCE YOUR DANCE FILM - the cinematographer point of view Your skills at the service of the movement and the choreographer - understand the language of the Dance and be able to transmute it into filmic images. 1. The Subject - The Dance is the Star When you film, frame and light the Dance, the primary subject is the Dance and the related movement, not the dancers, not the scenography, not the music, just the Dance nothing else. The Dance is about movement not about positions: when you film the dance you are filming the movement not a sequence of positions and in order to completely comprehend this concept you must understand what movement is: like the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze said “w e always tend to confuse movement with traversed space…” 1. The movement is the act of traversing, when you film the Dance you film an act not an aestheticizing image of a subject. At the beginning it is difficult to understand how to film something that is abstract like the movement but with practice you will start to focus on what really matters and you will start to forget about the dancers. Movement is life and the more you can capture it the more the characters are alive therefore more real in a way that you can almost touch them, almost dance with them. The Dance is a movement with a rhythm and when you film it you have to become part of the whole rhythm, like when you add an instrument to a music composition, the vocabulary of cinema is just another layer on the whole art work. -

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Index to Academy Oral Histories Leo C. Popkin

Index to Academy Oral Histories Leo C. Popkin Leo C. Popkin (Producer, Director, Exhibitor) Call number: OH142 Academy Award Theater (Los Angeles), 343–344, 354 Academy Awards, 26, 198, 255–256, 329 accounting, 110-111, 371 ACE IN THE HOLE, 326–327 acting, 93, 97, 102, 120–123, 126–130, 138–139, 161, 167–169, 173, 191, 231–234, 249–254, 260–261, 295–297, 337–342, 361–362, 367–368, 374-378, 381–383 Adler, Luther, 260–261, 284 advertising, 102-103, 140–142, 150–151, 194, 223–224 African-Americans and film, 186–190, 195–198, 388-392 African-Americans, depiction of, 111–112, 120–122, 126–130, 142–144, 156–158, 165- 173, 186–189, 199–200, 203, 206–211, 325, 338–351, 357, 388–392 African-American films, 70-214, 390-394 African-Americans in the film industry, 34–36, 43–45, 71–214, 339–341, 351–352, 388- 392 agents, 305-306, 361–362 Ahn, Philip, 251 alcoholism in films, 378 Aliso Theater (Los Angeles), 66 Allied Artists, 89 American Automobile Association (AAA), 315 American Federation of Musicians (Local 47 and Local 767, AFL), 34, 267, 274 American Legion Stadium (Hollywood), 55–56 Anaheim Drive-in Theater (Anaheim), 28, 69 AND THEN THERE WERE NONE, 11-12, 54, 114–120, 166, 224–236, 276, 278, 283, 302–304, 317–318 Anderson, Ernest, 339–341 Anderson, Judith, 226 Anderson, Richard, 382–383 Andriot, Lucien, 226, 230 Angel's Flight railway (Los Angeles), 50 animation, 222 anti-Semitism, 107 Apollo Theater (New York City), 45, 178–179, 352 architecture and film, 366–367 Armstrong, Louis, 133 art direction, 138, 162, 199, 221–222, 226, 264, 269, -

Choreography for the Camera: an Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1992 Choreography for the Camera: An Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study Vana Patrice Carter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, and the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Vana Patrice, "Choreography for the Camera: An Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study" (1992). Master's Theses. 894. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/894 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA: AN HISTORICAL, CRITICAL, AND EMPIRICAL STUDY by Vana Patrice Carter A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 1992 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA: AN HISTORICAL, CRITICAL, AND EMPIRICAL STUDY Vana Patrice Carter, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1992 This study investigates whether a dance choreographer’s lack of knowledge of film, television, or video theory and technology, particularly the capabilities of the camera and montage, restricts choreographic communication via these media. First, several film and television choreographers were surveyed. Second, the literature was analyzed to determine the evolution of dance on film and television (from the choreographers’ perspective). -

Shot and Captured Turf Dance, YAK Films, and the Oakland, California, R.I.P

Shot and Captured Turf Dance, YAK Films, and the Oakland, California, R.I.P. Project Naomi Bragin When a group comprised primarily of African-derived “people” — yes, the scare quotes matter — gather at the intersection of performance and subjectivity, the result is often [...] a palpable structure of feeling, a shared sense that violence and captivity are the grammar and ghosts of our every gesture. — Frank B. Wilderson, III (2009:119) barred gates hem sidewalk rain splash up on passing cars unremarkable two hooded figures stand by everyday grays wash street corner clean sweeps a cross signal tag white R.I.P. Haunt They haltingly disappear and reappear.1 The camera’s jump cut pushes them abruptly in and out of place. Cut. Patrol car marked with Oakland Police insignia momentarily blocks them from view. One pulls a 1. Turf Feinz dancers appearing in RIP RichD (in order of solos) are Garion “No Noize” Morgan, Leon “Mann” Williams, Byron “T7” Sanders, and Darrell “D-Real” Armstead. Dancers and Turf Feinz appearing in other TDR: The Drama Review 58:2 (T222) Summer 2014. ©2014 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 99 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/DRAM_a_00349 by guest on 01 October 2021 keffiyah down revealing brown. Skin. Cut. Patrol car turns corner, leaving two bodies lingering amidst distended strains of synthesizer chords. Swelling soundtrack. Close focus in on two street signs marking crossroads. Pan back down on two bodies. Identified. MacArthur and 90th. Swollen chords. In time to the drumbeat’s pickup, one ritually crosses himself. -

Department of Dance and Choreography 1

Department of Dance and Choreography 1 DANC 102. Modern Dance Technique I and Workshop. 3 Hours. DEPARTMENT OF DANCE AND Continuous courses; 1 lecture and 6 studio hours. 3-3 credits. These courses may be repeated for a maximum total of 12 credits on the CHOREOGRAPHY recommendation of the chair. Prerequisites: completion of DANC 101 to enroll in DANC 102. Dance major or departmental approval. Fundamental arts.vcu.edu/dance (http://arts.vcu.edu/dance/) study and training in principles of modern dance technique. Emphasis is on body alignment, spatial patterning, flexibility, strength and kinesthetic The VCU Department of Dance and Choreography offers a pre- awareness. Course includes weekly group exploration of techniques professional program that provides students with numerous related to all areas of dance. opportunities for individual artistic growth in a community that values communication, collaboration and self-motivation. The department DANC 103. Survey of Dance History. 3 Hours. provides an invigorating educational environment designed to prepare Continuous courses; 3 lecture hours. 3-3 credits. Prerequisites: students for the demands and challenges of a career as an informed and completion of DANC 103 to enroll in DANC 104. Dance major or engaged artist in the field of dance. departmental approval. First semester: dance from ritual to the contemporary ballet and the foundations of the Western aesthetic as it Graduates of the program thrive as performers, makers, teachers, relates to dance, and the development of the ballet. Second semester: administrators and in many other facets of the field of dance. Alongside Western concert dance from the aesthetic dance of the late 1800s general education courses, dance-focused academics and creative- to contemporary modern dance. -

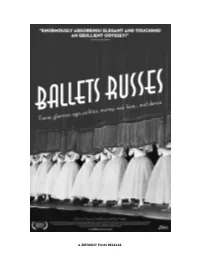

Ballets Russes Press

A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE THEY CAME. THEY DANCED. OUR WORLD WAS NEVER THE SAME. BALLETS RUSSES a film by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller Unearthing a treasure trove of archival footage, filmmakers Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine have fashioned a dazzlingly entrancing ode to the rev- olutionary twentieth-century dance troupe known as the Ballets Russes. What began as a group of Russian refugees who never danced in Russia became not one but two rival dance troupes who fought the infamous “ballet battles” that consumed London society before World War II. BALLETS RUSSES maps the company’s Diaghilev-era beginnings in turn- of-the-century Paris—when artists such as Nijinsky, Balanchine, Picasso, Miró, Matisse, and Stravinsky united in an unparalleled collaboration—to its halcyon days of the 1930s and ’40s, when the Ballets Russes toured America, astonishing audiences schooled in vaudeville with artistry never before seen, to its demise in the 1950s and ’60s when rising costs, rock- eting egos, outside competition, and internal mismanagement ultimately brought this revered company to its knees. Directed with consummate invention and infused with juicy anecdotal interviews from many of the company’s glamorous stars, BALLETS RUSSES treats modern audiences to a rare glimpse of the singularly remarkable merger of Russian, American, European, and Latin American dancers, choreographers, composers, and designers that transformed the face of ballet for generations to come. — Sundance Film Festival 2005 FILMMAKERS’ STATEMENT AND PRODUCTION NOTES In January 2000, our Co-Producers, Robert Hawk and Douglas Blair Turnbaugh, came to us with the idea of filming what they described as a once-in-a-lifetime event. -

3. Master the Camera

mini filmmaking guides production 3. MASTER THE CAMERA To access our full set of Into Film DEVELOPMENT (3 guides) mini filmmaking guides visit intofilm.org PRE-PRODUCTION (4 guides) PRODUCTION (5 guides) 1. LIGHT A FILM SET 2. GET SET UP 3. MASTER THE CAMERA 4. RECORD SOUND 5. STAY SAFE AND OBSERVE SET ETIQUETTE POST-PRODUCTION (2 guides) EXHIBITION AND DISTRIBUTION (2 guides) PRODUCTION MASTER THE CAMERA Master the camera (camera shots, angles and movements) Top Tip Before you begin making your film, have a play with your camera: try to film something! A simple, silent (no dialogue) scene where somebody walks into the shot, does something and then leaves is perfect. Once you’ve shot your first film, watch it. What do you like/dislike about it? Save this first attempt. We’ll be asking you to return to it later. (If you have already done this and saved your films, you don’t need to do this again.) Professional filmmakers divide scenes into shots. They set up their camera and frame the first shot, film the action and then stop recording. This process is repeated for each new shot until the scene is completed. The clips are then put together in the edit to make one continuous scene. Whatever equipment you work with, if you use professional techniques, you can produce quality films that look cinematic. The table below gives a description of the main shots, angles and movements used by professional filmmakers. An explanation of the effects they create and the information they can give the audience is also included.