Pearl Millet Santosh K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ehrharta Longiflora Sm. and Pennisetum Setaceum (Forsk

EHRHARTA LONGIFLORA SM. AND PENNISETUM SETACEUM (FORSK.) CHIOV., TWO NEW ALIEN GRASSES FOR MADEIRA ISLAND (PORTUGAL) Laura Cabral*, João Pedro Ferreira*, André Brazão* Pedro Nascimento* & Miguel Menezes de Sequeira** Abstract The number of introduced, and possible introduced, taxa in the Madeira and Selvagens islands currently accounts for nearly 36% of the total flora of these archipelagos, including 53 Poaceae taxa (out of 141 Poaceae taxa), therefore constituting the family with the higher proportion of introduced taxa (38.4%). The genus Ehrharta Thunb. comprises about 35 species, with one species, E. longiflora Sm., recorded as introduced in Gran Canaria. The genus Pennisetum Rich. includes ca. 80 species of which a total of nine species are present in Macaronesia, with three: P. clandestinum Hochst. & Chiov., P. purpureum Schum. and P. villosum R. Br. ex Fresen, occurring in the Madeira archipelago. Ehrharta longiflora Sm. and Pennisetum setaceum (Forssk.) Chiov., are here recorded for the first time for the Ma- deira island, found in disturbed areas at low and medium altitudes. The finding of several mature and flowering/fructifying individuals of both species suggests a fully naturalized status. Naturalization, invasiveness and ecological impacts are discussed. Keywords: alien, Ehrharta longiflora, grasses, Madeira, Pennisetum setaceum. EHRHARTA LONGIFLORA SM. Y PENNISETUM SETACEUM (FORSK.) CHIOV., DOS NUEVAS GRAMÍNEAS EXÓTICAS PARA LA ISLA DE MADEIRA (PORTUGAL) 133 Resumen El número de taxones introducidos y posiblemente introducidos en los archipiélagos de Ma- deira y Salvajes supone aproximadamente un 36% de su flora total, incluyendo 53 taxa de poáceas (sobre un total de 141 taxa de poáceas), constituyendo, de esta manera, la familia botánica con mayor número de taxa introducidos (38,4%). -

Effects of Fertilization and Harvesting Age on Yield and Quality of Desho

Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 2020; 9(4): 113-121 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/aff doi: 10.11648/j.aff.20200904.13 ISSN: 2328-563X (Print); ISSN: 2328-5648 (Online) Effects of Fertilization and Harvesting Age on Yield and Quality of Desho (Pennisetum pedicellatum ) Grass Under Irrigation, in Dehana District, Wag Hemra Zone, Ethiopia Awoke Kefyalew 1, Berhanu Alemu 2, Alemu Tsegaye 3 1Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture, Oda Bultum University, Chiro, Ethiopia 2Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Debre Markos University, Debre Markos, Ethiopia 3Sekota Dry Land Agricultural Research Center, Sekota, Ethiopia Email address: To cite this article: Awoke Kefyalew, Berhanu Alemu, Alemu Tsegaye. Effects of Fertilization and Harvesting Age on Yield and Quality of Desho (Pennisetum pedicellatum ) Grass Under Irrigation, in Dehana District, Wag Hemra Zone, Ethiopia. Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries . Vol. 9, No. 4, 2020, pp. 113-121. doi: 10.11648/j.aff.20200904.13 Received : June 5, 2020; Accepted : June 19, 2020; Published : July 28, 2020 Abstract: The experiment was conducted to evaluating the effects of fertilizer and harvesting age on agronomic performance, chemical composition and economic feasibility of Desho (Pennisetum Pedicellatum) grass under irrigation, in Ethiopia. A factorial arrangement with four fertilizer types (control, urea, compost and urea + compost), and three harvesting ages (90, 120 and 150) with three replications were used. Data on morphological characteristics of the grass were recorded. Based on the data collected, harvesting age was significantly affected the agronomic parameters of the grass. Plant height (PH), number of tillers per plant (NTPP), number of leaves per plant (NLPP), number of leaves per tiller (NLPT), dry matter yield (DMY), leaf length (LL) and leaf area (LA) were increased with increasing harvesting age, while leaf to stem ratio (LSR) showed a decreasing trend. -

The Story of Millets

The Story of Millets Millets were the first crops Millets are the future crops Published by: Karnataka State Department of Agriculture, Bengaluru, India with ICAR-Indian Institute of Millets Research, Hyderabad, India This document is for educational and awareness purpose only and not for profit or business publicity purposes 2018 Compiled and edited by: B Venkatesh Bhat, B Dayakar Rao and Vilas A Tonapi ICAR-Indian Institute of Millets Research, Hyderabad Inputs from: Prabhakar, B.Boraiah and Prabhu C. Ganiger (All Indian Coordinated Research Project on Small Millets, University of Agricultural Sciences, Bengaluru, India) Disclaimer The document is a compilation of information from reputed and some popular sources for educational purposes only. The authors do not claim ownership or credit for any content which may be a part of copyrighted material or otherwise. In many cases the sources of content have not been quoted for the sake of lucid reading for educational purposes, but that does not imply authors have claim to the same. Sources of illustrations and photographs have been cited where available and authors do not claim credit for any of the copy righted or third party material. G. Sathish, IFS, Commissioner for Agriculture, Department of Agriculture Government of Karnataka Foreword Millets are the ancient crops of the mankind and are important for rainfed agriculture. They are nutritionally rich and provide number of health benefits to the consumers. With Karnataka being a leading state in millets production and promotion, the government is keen on supporting the farmers and consumers to realize the full potential of these crops. On the occasion of International Organics and Millets Fair, 2018, we are planning before you a story on millets to provide a complete historic global perspective of journey of millets, their health benefits, utilization, current status and future prospects, in association with our knowledge partner ICAR - Indian Institute of Millets Research, with specific inputs from the University of Agricultural Sciences, Bengaluru. -

![Sorghum & Pearl Millet in Zambia: Production Guide, [2006]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8241/sorghum-pearl-millet-in-zambia-production-guide-2006-248241.webp)

Sorghum & Pearl Millet in Zambia: Production Guide, [2006]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln International Sorghum and Millet Collaborative INTSORMIL Scientific Publications Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) 9-30-2008 Sorghum & Pearl Millet in Zambia: Production Guide, [2006] Kimberley Christiansen INTSORMIL Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/intsormilpubs Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, Agriculture Commons, Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, and the Sales and Merchandising Commons Christiansen, Kimberley, "Sorghum & Pearl Millet in Zambia: Production Guide, [2006]" (2008). INTSORMIL Scientific Publications. 1. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/intsormilpubs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the International Sorghum and Millet Collaborative Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in INTSORMIL Scientific Publications yb an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Production Guide Sorghum & Pearl Millet in Zambia Foreword .................................................................................. I Acknowledgements ................................................................ II Introduction ........................................................................... III Chapter One: Sorghum ............................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ...................................................................... -

Improving Millet/Cowpea Intercropping in the Semi-Arid Zone of Mali

Improving millet/cowpea intercropping in the semi-arid zone of Mali * The original French paper 'Possibilites d'amelioration de 1'association culturale mil- niébé en zones semi-arides au Mali' is an updated version of a paper published in Haque et al (1986). H. HULET The Sahel Programme ILCA, P.O.Box 60, Bamako, Mali SUMMARY THE MILLET/COWPEA intercropping system used in the semi-arid zone of Mali is on the decline. ILCA's studies of the system during 1981-85 showed that grain and biomass yields can be improved by manipulating the planting date, pattern, and density of the crops and by rotating sole millet with millet/cowpea intercrops. Sowing millet and cowpea in separate holes on a ridge or on alternate ridges decreased millet grain yields less than when both crops were planted in the same hole. The optimum proportion of cowpea in the mixture was 15% without fertilizer and 45% when rock phosphate was applied. Rotating millet/cowpea intercrops with sole millet increased the grain yield of sole millet by 30%. Delayed sowing of the legume reduced interspecies competition, resulting in good grain and biomass yields. Cowpea proved to be more competitive than millet under dry conditions, while millet benefitted from intercropping in higher-rainfall areas. INTRODUCTION Millet (Pennisetum americanum) is intercropped with cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) on about 60% of the plots cultivated in semi-arid Mali (Diallo et al, 1985). Millet provides 70–90% of the food energy of the human population, and in some cases as much as 95% (Martin, 1985). Cowpea grain, which contains 20–25% protein, is valued as human food (Pugliese, 1984), and its haulms (14–30% net protein) are grazed by cattle during the dry season (Göh1, 1981; Skerman, 1982). -

On-Farm Evaluation on Yield and Economic Performance of Cereal-Cowpea Intercropping to Support the Smallholder Farming System in the Soudano-Sahelian Zone of Mali

agriculture Article On-Farm Evaluation on Yield and Economic Performance of Cereal-Cowpea Intercropping to Support the Smallholder Farming System in the Soudano-Sahelian Zone of Mali Bougouna Sogoba 1,2,* , Bouba Traoré 3,4 , Abdelmounaime Safia 1, Oumar Baba Samaké 2, Gilbert Dembélé 2, Sory Diallo 4, Roger Kaboré 2, Goze Bertin Benié 1, Robert B. Zougmoré 5 and Kalifa Goïta 1 1 Centre D’Applications et de Recherches en TéléDétection (CARTEL), Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC J1K 2R1, Canada; abdelmounaime.a.safi[email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (G.B.B.); [email protected] (K.G.) 2 ONG AMEDD (Association Malienne d’Éveil au Développement Durable) Darsalam II-Route de Ségou, Rue 316 porte 79, BP 212 Koutiala, Mali; [email protected] (O.B.S.); [email protected] (G.D.); [email protected] (R.K.) 3 International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT-Niger), BP 12404 Niamey, Niger; [email protected] 4 Institut D’Economie Rurale (IER)-Mali, BP 438 Bamako, Mali; [email protected] 5 CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), ICRISAT West and Central Africa Office, BP 320 Bamako, Mali; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 April 2020; Accepted: 6 June 2020; Published: 9 June 2020 Abstract: Cereal-cowpea intercropping has become an integral part of the farming system in Mali. Still, information is lacking regarding integrated benefits of the whole system, including valuing of the biomass for facing the constraints of animal feedings. We used farmers’ learning networks to evaluate performance of intercropping systems of millet-cowpea and sorghum-cowpea in southern Mali. -

Designing W Grasses Complete Notes

DESIGNING W/ GRASSES: SLIDESHOW NAMES TONY SPENCER Google search botanical plant names or visit Missouri Botanical Garden site for more info: 1. Pennisetum alopecuroides + Sanguisorba + Molinia arundinacea ‘Transparent’ 2. Pennisetum alopecuroides + Aster + Molinia arundinacea ‘Transparent’ 3. Calamagrostis x. acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’ + Panicum ‘Shenandoah’ 4. Helianthus pauciflorus – Photo Credit: Chris Helzer 5. Nassella tenuissima + Echinacea simulata + Monarda bradburiana 6. Hordeum jubatum + Astilbe 7. Deschampsia cespitosa + Helenium autumnale 8. Calamagrostis brachytricha + Miscanthus sinensis + Cimicifuga atropurpurea 9. Sporobolus heterlolepis + Echinacea pallida 10. Panicum virgatum + Echinacea pallida + Monarda + Veronica 11. Molinia arundinacea ‘Transparent + Sanguisorba officinalis 12. Bouteloua gracilis 13. Calamagrostis brachytricha + Helenium autumnale 14. Peucedanum verticillare 15. Anemone ‘Honorine Jobert’ 2016 Perennial Plant of the Year 16. Miscanthus sinsensis 17. Calamagrostis brachytricha 18. Molinia caerulea + Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ 19. Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ + Lythrum alatum + Parthenium integrafolium 20. Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’ 21. Bouteloua gracilis + Echinacea ‘Kim’s Knee High’ + Salvia nemorosa 22. Baptisia alba 23. Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ in Hummelo meadow planting 24. Panicum amarum ‘Dewey Blue’ + Helenium autumnale 25. Deschampsia cespitosa 26. Echinacea purpurea seedheads 27. Calamagrostis brachytricha + Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ + Echinacea + Veronicastrum + Eupatorium -

Risk Analysis of Alien Grasses Occurring in South Africa

Risk analysis of alien grasses occurring in South Africa By NKUNA Khensani Vulani Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at Stellenbosch University (Department of Botany and Zoology) Supervisor: Dr. Sabrina Kumschick Co-supervisor (s): Dr. Vernon Visser : Prof. John R. Wilson Department of Botany & Zoology Faculty of Science Stellenbosch University December 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis/dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: December 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Alien grasses have caused major impacts in their introduced ranges, including transforming natural ecosystems and reducing agricultural yields. This is clearly of concern for South Africa. However, alien grass impacts in South Africa are largely unknown. This makes prioritising them for management difficult. In this thesis, I investigated the negative environmental and socio-economic impacts of 58 alien grasses occurring in South Africa from 352 published literature sources, the mechanisms through which they cause impacts, and the magnitudes of those impacts across different habitats and regions. Through this assessment, I ranked alien grasses based on their maximum recorded impact. Cortaderia sellonoana had the highest overall impact score, followed by Arundo donax, Avena fatua, Elymus repens, and Festuca arundinacea. -

Ornamental Grasses for Kentucky Landscapes Lenore J

HO-79 Ornamental Grasses for Kentucky Landscapes Lenore J. Nash, Mary L. Witt, Linda Tapp, and A. J. Powell Jr. any ornamental grasses are available for use in resi- Grasses can be purchased in containers or bare-root Mdential and commercial landscapes and gardens. This (without soil). If you purchase plants from a mail-order publication will help you select grasses that fit different nursery, they will be shipped bare-root. Some plants may landscape needs and grasses that are hardy in Kentucky not bloom until the second season, so buying a larger plant (USDA Zone 6). Grasses are selected for their attractive foli- with an established root system is a good idea if you want age, distinctive form, and/or showy flowers and seedheads. landscape value the first year. If you order from a mail- All but one of the grasses mentioned in this publication are order nursery, plants will be shipped in spring with limited perennial types (see Glossary). shipping in summer and fall. Grasses can be used as ground covers, specimen plants, in or near water, perennial borders, rock gardens, or natu- Planting ralized areas. Annual grasses and many perennial grasses When: The best time to plant grasses is spring, so they have attractive flowers and seedheads and are suitable for will be established by the time hot summer months arrive. fresh and dried arrangements. Container-grown grasses can be planted during the sum- mer as long as adequate moisture is supplied. Cool-season Selecting and Buying grasses can be planted in early fall, but plenty of mulch Select a grass that is right for your climate. -

Fountain Grass

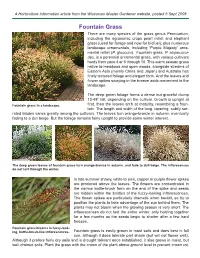

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 5 Sept 2008 Fountain Grass There are many species of the grass genus Pennisetum, including the agronomic crops pearl millet and elephant grass (used for forage and now for biofuel), plus numerous landscape ornamentals, including ‘Purple Majesty’ orna- mental millet (P. glaucum). Fountain grass, P. alopecuroi- des, is a perennial ornamental grass, with various cultivars hardy from zone 4 or 5 through 10. This warm season grass native to meadows and open woods, alongside streams of Eastern Asia (mainly China and Japan) and Australia has fi nely textured foliage and elegant form. And the leaves and fl ower spikes swaying in the breeze adds movement to the landscape. The deep green foliage forms a dense but graceful clump 12-48” tall, depending on the cultivar. Growth is upright at Fountain grass in a landscape. fi rst, then the leaves arch at maturity, resembling a foun- tain. The length and width of the long, tapering, subtly ser- rated blades varies greatly among the cultivars. The leaves turn orange-bronze in autumn, eventually fading to a dull beige. But the foliage remains fairly upright to provide some winter interest. The deep green leaves of fountain grass turn orange-bronze in autumn, and fade to dull beige. The infl oresences do not last through the winter. In late summer showy, white to pink, copper or purple fl ower spikes are produced above the leaves. The fl owers are concentrated in the narrow bottle-brush form on the end of the spike and seeds are hidden within the bristles of the fuzzy-looking infl orescences. -

Missouriensis

Missouriensis Journal of the Missouri Native Plant Society Volume 34 2017 effectively published online 30 September 2017 Missouriensis, Volume 34 (2017) Journal of the Missouri Native Plant Society EDITOR Douglas Ladd Missouri Botanical Garden P.O. Box 299 St. Louis, MO 63110 email: [email protected] MISSOURI NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY https://monativeplants.org PRESIDENT VICE-PRESIDENT John Oliver Dana Thomas 4861 Gatesbury Drive 1530 E. Farm Road 96 Saint Louis, MO 63128 Springfield, MO 65803 314.487.5924 317.430.6566 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] SECRETARY TREASURER Malissa Briggler Bob Siemer 102975 County Rd. 371 74 Conway Cove Drive New Bloomfield, MO 65043 Chesterfield, MO 63017 573.301.0082 636.537.2466 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT WEBMASTER Paul McKenzie Brian Edmond 2311 Grandview Circle 8878 N Farm Road 75 Columbia, MO 65203 Walnut Grove, MO 65770 573.445.3019 417.742.9438 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] BOARD MEMBERS Steve Buback, St. Joseph (2015-2018); email: [email protected] Ron Colatskie, Festus (2016-2019); email: [email protected] Rick Grey, St. Louis (2015-2018); email: [email protected] Bruce Schuette, Troy (2016-2019); email: [email protected] Mike Skinner, Republic (2016-2019); email: [email protected] Justin Thomas, Springfield (2014-2017); email: [email protected] i FROM THE EDITOR Welcome to the first online edition of Missouriensis. The format has been redesigned to facilitate access and on-screen readability, and articles are freely available online as open source, archival pdfs. -

Pearl Millet, Foxtail Millet, Proso Millet, Oats, Sudangrass, Sorghum, and Sorghum-Sudan Hybrids Can Be Planted As Annual Forages

R-1016, May 1991 Kevin K. Sedivec, Extension Rangeland Management Specialist Blaine G. Schatz, Associate Agronomist, Carrington Research Center The acreage of crops planted for annual forage production in North Dakota is minor but increases dramatically at times of drought and when severe winter-kill of alfalfa occurs. Crops such as pearl millet, foxtail millet, proso millet, oats, sudangrass, sorghum, and sorghum-sudan hybrids can be planted as annual forages. Pearl millet is a relatively new forage in the northern regions of the United States. However, it has been utilized extensively as a high quality grazing forage in the southern United States. It was introduced into South Dakota in the early 1980s and has received favorable consideration as a forage crop in North Dakota recently Description Pearl millet (Pennisetum typhoides) is a tall, warm season, annual grass. It originated in Africa and India where it was used for both forage and grain. It was introduced into the United States in the 1850s and became established as a minor forage crop in the southeastern and Gulf Coast states. Pearl millet is also referred to as penicillaria, pencilaria, Mand's forage plant, cattail millet, bulrush millet, and candle millet. Pearl millet may grow 6 to 10 feet tall during conditions of high temperatures and favorable moisture. Improved varieties or hybrids are generally leafier and shorter than older varieties. The solid stems are often densely hairy and usually 3/8 to 3/4 inch in diameter. Leaves are long, scabrous, rather slender, and may be smooth or have hairy surfaces. Leaves, as well as stems, may vary in color from light yellowish green to deep purple.