Fall 2020 Volume 11, Issue 2 a Publication of the Maryland Native

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Designing W Grasses Complete Notes

DESIGNING W/ GRASSES: SLIDESHOW NAMES TONY SPENCER Google search botanical plant names or visit Missouri Botanical Garden site for more info: 1. Pennisetum alopecuroides + Sanguisorba + Molinia arundinacea ‘Transparent’ 2. Pennisetum alopecuroides + Aster + Molinia arundinacea ‘Transparent’ 3. Calamagrostis x. acutiflora ‘Karl Foerster’ + Panicum ‘Shenandoah’ 4. Helianthus pauciflorus – Photo Credit: Chris Helzer 5. Nassella tenuissima + Echinacea simulata + Monarda bradburiana 6. Hordeum jubatum + Astilbe 7. Deschampsia cespitosa + Helenium autumnale 8. Calamagrostis brachytricha + Miscanthus sinensis + Cimicifuga atropurpurea 9. Sporobolus heterlolepis + Echinacea pallida 10. Panicum virgatum + Echinacea pallida + Monarda + Veronica 11. Molinia arundinacea ‘Transparent + Sanguisorba officinalis 12. Bouteloua gracilis 13. Calamagrostis brachytricha + Helenium autumnale 14. Peucedanum verticillare 15. Anemone ‘Honorine Jobert’ 2016 Perennial Plant of the Year 16. Miscanthus sinsensis 17. Calamagrostis brachytricha 18. Molinia caerulea + Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ 19. Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ + Lythrum alatum + Parthenium integrafolium 20. Panicum virgatum ‘Shenandoah’ 21. Bouteloua gracilis + Echinacea ‘Kim’s Knee High’ + Salvia nemorosa 22. Baptisia alba 23. Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ in Hummelo meadow planting 24. Panicum amarum ‘Dewey Blue’ + Helenium autumnale 25. Deschampsia cespitosa 26. Echinacea purpurea seedheads 27. Calamagrostis brachytricha + Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ + Echinacea + Veronicastrum + Eupatorium -

Ornamental Grasses for Kentucky Landscapes Lenore J

HO-79 Ornamental Grasses for Kentucky Landscapes Lenore J. Nash, Mary L. Witt, Linda Tapp, and A. J. Powell Jr. any ornamental grasses are available for use in resi- Grasses can be purchased in containers or bare-root Mdential and commercial landscapes and gardens. This (without soil). If you purchase plants from a mail-order publication will help you select grasses that fit different nursery, they will be shipped bare-root. Some plants may landscape needs and grasses that are hardy in Kentucky not bloom until the second season, so buying a larger plant (USDA Zone 6). Grasses are selected for their attractive foli- with an established root system is a good idea if you want age, distinctive form, and/or showy flowers and seedheads. landscape value the first year. If you order from a mail- All but one of the grasses mentioned in this publication are order nursery, plants will be shipped in spring with limited perennial types (see Glossary). shipping in summer and fall. Grasses can be used as ground covers, specimen plants, in or near water, perennial borders, rock gardens, or natu- Planting ralized areas. Annual grasses and many perennial grasses When: The best time to plant grasses is spring, so they have attractive flowers and seedheads and are suitable for will be established by the time hot summer months arrive. fresh and dried arrangements. Container-grown grasses can be planted during the sum- mer as long as adequate moisture is supplied. Cool-season Selecting and Buying grasses can be planted in early fall, but plenty of mulch Select a grass that is right for your climate. -

Fountain Grass

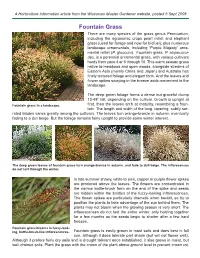

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 5 Sept 2008 Fountain Grass There are many species of the grass genus Pennisetum, including the agronomic crops pearl millet and elephant grass (used for forage and now for biofuel), plus numerous landscape ornamentals, including ‘Purple Majesty’ orna- mental millet (P. glaucum). Fountain grass, P. alopecuroi- des, is a perennial ornamental grass, with various cultivars hardy from zone 4 or 5 through 10. This warm season grass native to meadows and open woods, alongside streams of Eastern Asia (mainly China and Japan) and Australia has fi nely textured foliage and elegant form. And the leaves and fl ower spikes swaying in the breeze adds movement to the landscape. The deep green foliage forms a dense but graceful clump 12-48” tall, depending on the cultivar. Growth is upright at Fountain grass in a landscape. fi rst, then the leaves arch at maturity, resembling a foun- tain. The length and width of the long, tapering, subtly ser- rated blades varies greatly among the cultivars. The leaves turn orange-bronze in autumn, eventually fading to a dull beige. But the foliage remains fairly upright to provide some winter interest. The deep green leaves of fountain grass turn orange-bronze in autumn, and fade to dull beige. The infl oresences do not last through the winter. In late summer showy, white to pink, copper or purple fl ower spikes are produced above the leaves. The fl owers are concentrated in the narrow bottle-brush form on the end of the spike and seeds are hidden within the bristles of the fuzzy-looking infl orescences. -

Missouriensis

Missouriensis Journal of the Missouri Native Plant Society Volume 34 2017 effectively published online 30 September 2017 Missouriensis, Volume 34 (2017) Journal of the Missouri Native Plant Society EDITOR Douglas Ladd Missouri Botanical Garden P.O. Box 299 St. Louis, MO 63110 email: [email protected] MISSOURI NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY https://monativeplants.org PRESIDENT VICE-PRESIDENT John Oliver Dana Thomas 4861 Gatesbury Drive 1530 E. Farm Road 96 Saint Louis, MO 63128 Springfield, MO 65803 314.487.5924 317.430.6566 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] SECRETARY TREASURER Malissa Briggler Bob Siemer 102975 County Rd. 371 74 Conway Cove Drive New Bloomfield, MO 65043 Chesterfield, MO 63017 573.301.0082 636.537.2466 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT WEBMASTER Paul McKenzie Brian Edmond 2311 Grandview Circle 8878 N Farm Road 75 Columbia, MO 65203 Walnut Grove, MO 65770 573.445.3019 417.742.9438 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] BOARD MEMBERS Steve Buback, St. Joseph (2015-2018); email: [email protected] Ron Colatskie, Festus (2016-2019); email: [email protected] Rick Grey, St. Louis (2015-2018); email: [email protected] Bruce Schuette, Troy (2016-2019); email: [email protected] Mike Skinner, Republic (2016-2019); email: [email protected] Justin Thomas, Springfield (2014-2017); email: [email protected] i FROM THE EDITOR Welcome to the first online edition of Missouriensis. The format has been redesigned to facilitate access and on-screen readability, and articles are freely available online as open source, archival pdfs. -

Ornamental Grasses for the Midsouth Landscape

Ornamental Grasses for the Midsouth Landscape Ornamental grasses with their variety of form, may seem similar, grasses vary greatly, ranging from cool color, texture, and size add diversity and dimension to season to warm season grasses, from woody to herbaceous, a landscape. Not many other groups of plants can boast and from annuals to long-lived perennials. attractiveness during practically all seasons. The only time This variation has resulted in five recognized they could be considered not to contribute to the beauty of subfamilies within Poaceae. They are Arundinoideae, the landscape is the few weeks in the early spring between a unique mix of woody and herbaceous grass species; cutting back the old growth of the warm-season grasses Bambusoideae, the bamboos; Chloridoideae, warm- until the sprouting of new growth. From their emergence season herbaceous grasses; Panicoideae, also warm-season in the spring through winter, warm-season ornamental herbaceous grasses; and Pooideae, a cool-season subfamily. grasses add drama, grace, and motion to the landscape Their habitats also vary. Grasses are found across the unlike any other plants. globe, including in Antarctica. They have a strong presence One of the unique and desirable contributions in prairies, like those in the Great Plains, and savannas, like ornamental grasses make to the landscape is their sound. those in southern Africa. It is important to recognize these Anyone who has ever been in a pine forest on a windy day natural characteristics when using grasses for ornament, is aware of the ethereal music of wind against pine foliage. since they determine adaptability and management within The effect varies with the strength of the wind and the a landscape or region, as well as invasive potential. -

Pennisetum Alopecuroides 'Weserbergland'1

Fact Sheet FPS-462 October, 1999 Pennisetum alopecuroides ‘Weserbergland’1 Edward F. Gilman2 Introduction ‘Waserbergland’ is a dwarf cultivar of Fountain Grass that often reaches 3-feet-tall and wide (Fig. 1). It grows slightly larger than ‘Hameln’. The white inflorescence resembles a bottle brush and persists into fall. These attractive, 5- to 7- inch-long flowers persist on the plant from summer to fall but shatter in the early winter. The foliage of Fountain Grass is bright green during the summer, but turns to a golden brown color in the fall after the flowers begin to die. The foliage arches near the tip and gives the plant a graceful fountain shape. Fountain Grass is an outstanding, elegant, fine-textured ornamental grass. General Information Scientific name: Pennisetum alopecuroides ‘Weserbergland’ Pronunciation: pen-niss-SEE-tum al-loe-peck-yer-ROY-deez Common name(s): ‘Weserbergland’ Fountain Grass Family: Gramineae Plant type: ornamental grass; herbaceous USDA hardiness zones: 5 through 8 (Fig. 2) Figure 1. ‘Weserbergland’ Fountain Grass. Planting month for zone 7: year round Planting month for zone 8: year round Origin: not native to North America Description Uses: mass planting; container or above-ground planter; accent; Height: 2 to 4 feet border; cut flowers Spread: 2 to 3 feet Availablity: somewhat available, may have to go out of the Plant habit: upright region to find the plant Plant density: moderate Growth rate: fast Texture: fine 1.This document is Fact Sheet FPS-462, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

PRE Evaluation Report for Pennisetum

PRE Evaluation Report -- Pennisetum alopecuroides Plant Risk Evaluator -- PRE™ Evaluation Report Pennisetum alopecuroides -- Illinois 2017 Farm Bill PRE Project PRE Score: 16 -- Reject (high risk of invasiveness) Confidence: 63 / 100 Questions answered: 20 of 20 -- Valid (80% or more questions answered) Privacy: Public Status: Submitted Evaluation Date: September 4, 2017 This PDF was created on June 15, 2018 Page 1/19 PRE Evaluation Report -- Pennisetum alopecuroides Plant Evaluated Pennisetum alopecuroides Image by André Karwath Page 2/19 PRE Evaluation Report -- Pennisetum alopecuroides Evaluation Overview A PRE™ screener conducted a literature review for this plant (Pennisetum alopecuroides) in an effort to understand the invasive history, reproductive strategies, and the impact, if any, on the region's native plants and animals. This research reflects the data available at the time this evaluation was conducted. Summary Pennisetum alopecuroides (Cenchrus purpurascens) appears to present a high risk of invasiveness in Illinois. The plant produces copious viable seeds which can be moved great distances by multiple means. Promoting fire and invading pastures could have a significant impact on other plants and animals, though evidence for these impacts is speculative. Populations in the wild in the US seem to be relatively recent. It's noted as an emerging invasive in the Mid-Atlantic states. Only one city and county in Virginia are currently listing it as invasive. Pennisetum alopecuroides therefore presents a risk and should be closely -

Meyer Phd.Pdf (3.220Mb Application/Pdf)

INHERITANCE OF GROWTH HABIT AND PHOSPHOGLUCOISOMERASE ISOZYMES IN PENNISETUM ALOPECUROIDES (L.) SPRENG. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY MARY HOCKENBERRY MEYER IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY MAY 1993 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA This is to certify that I have examined this bound copy of a doctoral thesis by Mary Hockenberry Meyer and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Donald B. White Name of Faculty Advisor Signature of Faculty Advisor GRADUATE SCHOOL copyright Mary Hockenberry Meyer 1993 This thesis is dedicated to my parents, William Wadsworth Hockenberry and l f Thorene Anderson Hockenberry I t I iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research would not have been possible without the support and assistance of my committee. Special thanks to my advisor, D.B. White, who gave countless hours of advice and guidance; to H. M. Pellett, who not only gave support with time and technical advice, but agreed to purchase the large collection of ornamental grasses at the arboretum; to P.O. Ascher, for his expertise on breeding and analysis of the growth habit segregations; to v. M. Mikelonis, who guided me through minoring in scientific and technical conununications; and to J. E. Connolly and R. w. Ferguson, for their classes and advice in writing and oral presentations as well as serving on my committee. Countless others have lent support and assistance over the years, especially Roger Meissner, Dave Olson, Martha Piechowski, and Karl Ruser. -

Salt and Drought Tolerance of Four Ornamental Grasses

SALT AND DROUGHT TOLERANCE OF FOUR ORNAMENTAL GRASSES By ERIN ELIZABETH ALVAREZ A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCEINCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 1 Copyright 2006 by Erin Elizabeth Alvarez 2 To my father for his unwavering pride and support 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my family and friends for their constant support and love. I thank Michele Scheiber for going above and beyond the call of duty. I would also like to thank David Sandrock, and Richard Beeson for their assistance in completing this project. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 LIST OF TABLES...........................................................................................................................7 LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................8 ABSTRACT.....................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................11 Drought Tolerance..................................................................................................................11 Salt Tolerance. ........................................................................................................................12 -

(12) United States Plant Patent (10) Patent No.: US PP19,074 P2 Horvath (45) Date of Patent: Aug

USOOPP19074P2 (12) United States Plant Patent (10) Patent No.: US PP19,074 P2 Horvath (45) Date of Patent: Aug. 5, 2008 (54) PENNISETUM ALOPECUROIDES PLANT (52) U.S. Cl. ....................................................... Pt/384 NAMED PGLET (58) Field of Classification Search ........................ None See application file for complete search history. (50) Latin Name: Pennisetum alopecuroides Varietal Denomination: Piglet (56) References Cited (76) Inventor: Brent Horvath, 10702 Seaman Rd., U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS Hebron, IL (US) 60034 PP18,509 P3 * 2/2008 Hanna et al. ................ Plt,384 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this * cited by examiner patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S.C. 154(b) by 105 days. Primary Examiner Wendy C. Haas (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm Brent Horvath (21) Appl. No.: 11/593,612 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Nov. 7, 2006 A new, distinct Pennisetum alopecuroides plant as shown and described, characterized by a short habit of 40-45 cm. (51) Int. Cl. AOIH 5/00 (2006.01) 1 Drawing Sheet 1. 2 Latin name: Pennisetum alopecuroides. length of 7-8 cm compared to Pennisetum alopecuroides Cultivar name: Piglet. Hameln which has an the inflorescence length of 10 cm. Plants of the new Pennisetum can be compared to plants of BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION Pennisetum alopecuroides Little Bunny, not patented. 1. 5 The new Pennisetum has a height of 45 cm compared to the The present invention relates to a new form of Pennisetum height of Pennisetum alopecuroides Little Bunny which alopecuroides plant named Piglet. Piglet is a seedling of has a height of 30 cm. 2. -

Illustration Sources

APPENDIX ONE ILLUSTRATION SOURCES REF. CODE ABR Abrams, L. 1923–1960. Illustrated flora of the Pacific states. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. ADD Addisonia. 1916–1964. New York Botanical Garden, New York. Reprinted with permission from Addisonia, vol. 18, plate 579, Copyright © 1933, The New York Botanical Garden. ANDAnderson, E. and Woodson, R.E. 1935. The species of Tradescantia indigenous to the United States. Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Reprinted with permission of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. ANN Hollingworth A. 2005. Original illustrations. Published herein by the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Fort Worth. Artist: Anne Hollingworth. ANO Anonymous. 1821. Medical botany. E. Cox and Sons, London. ARM Annual Rep. Missouri Bot. Gard. 1889–1912. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis. BA1 Bailey, L.H. 1914–1917. The standard cyclopedia of horticulture. The Macmillan Company, New York. BA2 Bailey, L.H. and Bailey, E.Z. 1976. Hortus third: A concise dictionary of plants cultivated in the United States and Canada. Revised and expanded by the staff of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium. Cornell University. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. Reprinted with permission from William Crepet and the L.H. Bailey Hortorium. Cornell University. BA3 Bailey, L.H. 1900–1902. Cyclopedia of American horticulture. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York. BB2 Britton, N.L. and Brown, A. 1913. An illustrated flora of the northern United States, Canada and the British posses- sions. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. BEA Beal, E.O. and Thieret, J.W. 1986. Aquatic and wetland plants of Kentucky. Kentucky Nature Preserves Commission, Frankfort. Reprinted with permission of Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission. -

Evolution of the Apomixis Transmitting Chromosome in Pennisetum

Akiyama et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2011, 11:289 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/11/289 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Evolution of the apomixis transmitting chromosome in Pennisetum Yukio Akiyama1†, Shailendra Goel1†, Joann A Conner1, Wayne W Hanna2, Hitomi Yamada-Akiyama3 and Peggy Ozias-Akins1* Abstract Background: Apomixis is an intriguing trait in plants that results in maternal clones through seed reproduction. Apomixis is an elusive, but potentially revolutionary, trait for plant breeding and hybrid seed production. Recent studies arguing that apomicts are not evolutionary dead ends have generated further interest in the evolution of asexual flowering plants. Results: In the present study, we investigate karyotypic variation in a single chromosome responsible for transmitting apomixis, the Apospory-Specific Genomic Region carrier chromosome, in relation to species phylogeny in the genera Pennisetum and Cenchrus. A 1 kb region from the 3’ end of the ndhF gene and a 900 bp region from trnL-F were sequenced from 12 apomictic and eight sexual species in the genus Pennisetum and allied genus Cenchrus. An 800 bp region from the Apospory-Specific Genomic Region also was sequenced from the 12 apomicts. Molecular cytological analysis was conducted in sixteen Pennisetum and two Cenchrus species. Our results indicate that the Apospory-Specific Genomic Region is shared by all apomictic species while it is absent from all sexual species or cytotypes. Contrary to our previous observations in Pennisetum squamulatum and Cenchrus ciliaris, retrotransposon sequences of the Opie-2-like family were not closely associated with the Apospory-Specific Genomic Region in all apomictic species, suggesting that they may have been accumulated after the Apospory-Specific Genomic Region originated.