Spring Awakening and Anti-Conformity: an Ideological Criticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JERSEY BOYS and KINKY BOOTS Highlight the 2017-18 Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Reida York Director of Advertising and Public Relations 816.559.3847 office | 816.668.9321 cell [email protected] JERSEY BOYS and KINKY BOOTS Highlight the 2017-18 Broadway at The Orpheum Theatre Series PHOENIX, AZ – The Tony Award®-winning Best Musicals JERSEY BOYS and KINKY BOOTS highlight the 2017-18 Broadway at The Orpheum Theatre Series, presented by Theater League in Phoenix, Arizona, at the beautiful Orpheum Theatre. Season renewals and priority orders are available at BroadwayOrpheum.com or by calling 800.776.7469. “We are thrilled to bring such powerful productions to the Orpheum Theatre,” Theater League President Mark Edelman said. “We are honored to be a part of this community and we look forward to contributing to the arts and culture of Phoenix with this strong season.” The Broadway in Thousand Oaks line-up features the best of Broadway, including the international sensation, JERSEY BOYS, the high-heeled hit, KINKY BOOTS, the nostalgic standard, MUSIC MAN: IN CONCERT, and the legendary classic, A CHORUS LINE. The 2017-18 Broadway at The Orpheum Theatre Series includes the following hit musicals: MUSIC MAN: IN CONCERT December 1-3, 2017 A Broadway classic in concert featuring the nostalgic score of rousing marches, barbershop quartets and sentimental ballads, which have become popular standards. Meredith Willson’s musical comedy has been delighting audiences since 1957 and is sure to entertain every generation. Harold Hill is a traveling con man, set to pull a fast one on the people of River City, Iowa, by promising to put together a boys band and selling instruments — despite the fact he knows nothing about music. -

YMTC to Present the Rock Musical Rent, November 3–10 in El Cerrito

Youth Musical Theater Company FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Inquiries: Laura Soble/YMTC Phone 510-595-5514 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.ymtcbayarea.org YMTC to Present the Rock Musical Rent, November 3–10 in El Cerrito Berkeley, California, September 27, 2019—Youth Musical Theater Company (YMTC) will launch its 15th season of acclaimed regional theater with the rock musical Rent. The show opens Sunday, November 3, at the Performing Arts Theater, 540 Ashbury Ave., El Cerrito. Its run consists of a 5:00 p.m. opening (11/3), two 2:00 p.m. matinees (11/9, 11/10), and three 7:30 p.m. performances (11/7, 11/8, 11/9). Rent is a rock opera loosely based on Puccini’s La Boheme, with music, lyrics, and book by Jonathan Larson. Set in Lower Manhattan’s East Village during the turmoil of the AIDS crisis, this moving story chronicles the lives of a group of struggling artists over a year’s time. Its major themes are community, friendship, and survival. In 1996, Rent received four Tony Awards, including Best Musical; six Drama Desk Awards; and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. In 1997, it won the Grammy Award for Best Musical Show Album. Its Broadway run lasted 12 years. Co-Director Jennifer Boesing comments, “Rent is a love story and a bold, brazen manifesto for young artists who are trying not just to stay alive, but to stay connected to each other, when the mainstream culture seems to be ignoring signs of destruction all around them. Although the show today is a period piece about a very specific historical moment—well before the earliest memories of our young performing artists—they relate to it deeply just the same. -

Musical Theatre at the Academy

MUSICAL THEATRE AT THE ACADEMY “Cole Porter Medley” at Showcase 2019 In the Musical Theatre Department, students master storytelling in three different disciplines: voice, dance, and acting. While many graduates of The Academy attend highly regarded BFA conservatory If you are looking for a career in the arts, the programs in musical theatre or acting, training that you get here is second to none. I others choose to pursue their training can’t imagine what it would be like in a regular in academic BA programs at liberal arts high school musical theatre program. We do colleges. two to three challenging musical productions a For Musical Theatre students, performance year, in addition to a Shakespeare festival. You is a key part of learning, and students have get so much exposure to different works and ample opportunity for it. The Department techniques that by the time you are going to produces three to four mainstage college, you have the confidence to audition shows per year, including two musical productions, and several plays as part of and succeed.” the Shakespeare Festival collaboration with - Jack, Musical Theatre ‘18 the Theatre Department. In acting classes, freshman and sophomore students focus their studies on the work of Shakespeare and Thornton Wilder, while juniors concentrate on Oscar Wilde and Tennessee Williams. Seniors begin to study the work of Anton Chekhov. chicagoacademyforthearts.org 312.421.0202 MUSICAL THEATRE AT THE ACADEMY Musical Theatre Department Curriculum Musical Theatre Department students are immersed in -

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

42Nd Street Center for Performing Arts

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia Center for Performing Arts 5-25-1996 42nd Street Center for Performing Arts Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia Recommended Citation Center for Performing Arts, "42nd Street" (1996). Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia. Book 82. http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia/82 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Performing Arts at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 42ND STREET Saturday, May 25 IP Ml" :• i fi THE CENTER FOR ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY AT GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY The Troika Organization, Music Theatre Associates, The A.C. Company, Inc., Nicholas Hovvey, Dallett Norris, Thomas J. Lydon, and Stephen B. Kane present Music by Lyrics by HARRY WARREN AL DUBIN Book by MICHAEL STEWART & MARK BRAMBLE Based on the novel by BRADFORD ROPES Original Direction and Dances by Originally Produced on Broadway by GOWER CHAMPION DAVID MERRICK Featuring ROBERT SHERIDAN REBECCA CHRISTINE KUPKA MICHELLE FELTEN MARC KESSLER KATHY HALENDA CHRISTOPHER DAUPHINEE NATALIE SLIPKO BRIANW.WEST SHAWN EMAMJOMEH MICHAEL SHILES Scenic Design by Costume Design by Lighting Design by JAMES KRONZER NANZI ADZIMA MARY JO DONDLINGER Sound Design by Hair and Makeup Design by Asst. Director/Choreographer KEVIN HIGLEY JOHN JACK CURTIN LeANNE SCHINDLER Orchestral & Vocal Arranger Musical Director & Conductor STEPHEN M. BISHOP HAMPTON F. KING, JR. -

Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: the Musical Katherine B

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 "Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The Musical Katherine B. Marcus Reker Scripps College Recommended Citation Marcus Reker, Katherine B., ""Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The usicalM " (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 876. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/876 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CAN WE DO A HAPPY MUSICAL NEXT TIME?”: NAVIGATING BRECHTIAN TRADITION AND SATIRICAL COMEDY THROUGH HOPE’S EYES IN URINETOWN: THE MUSICAL BY KATHERINE MARCUS REKER “Nothing is more revolting than when an actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing.” – Bertolt Brecht SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS GIOVANNI ORTEGA ARTHUR HOROWITZ THOMAS LEABHART RONNIE BROSTERMAN APRIL 22, 2016 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the support of the entire Faculty, Staff, and Community of the Pomona College Department of Theatre and Dance. Thank you to Art, Sherry, Betty, Janet, Gio, Tom, Carolyn, and Joyce for teaching and supporting me throughout this process and my time at Scripps College. Thank you, Art, for convincing me to minor and eventually major in this beautiful subject after taking my first theatre class with you my second year here. -

JERSEY BOYS Added to 2021 STAGES St

NEWS RELEASE For More Information Please Contact: Brett Murray [email protected] 636.449.5773 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (9/21/2020) STAGES ST. LOUIS ANNOUNCES BROADWAY STAR AND BROADWAY HIT TO HEADLINE 35TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON Tony Award-Winning JERSEY BOYS and Broadway Star Diana DeGarmo headline STAGES 35th Anniversary Season. (ST. LOUIS) – STAGES St. Louis is thrilled to announce its spectacular 35th Anniversary Season! The 2021 Season includes the much requested return of the most popular show in STAGES history, ALWAYS… PATSY CLINE, the Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-Winning masterpiece, A CHORUS LINE, the STAGES premiere of the Broadway sensation, JERSEY BOYS, and our Family Theatre Series production of the delightful A YEAR WITH FROG AND TOAD. 2021 not only marks the 35th Anniversary Season for STAGES, but also the move into the organization’s new artistic home in The Ross Family Theatre at the Kirkwood Performing Arts Center. The 40,000 square foot state-of-the-art facility features the 529-seat Ross Family Theatre, where all future productions of the Mainstage Season will play, and a flexible studio theatre, which will serve as home for the Family Theatre Series. “We could not be more excited to bring you a year of true blockbusters for our Inaugural Season at the Kirkwood Performing Arts Center!” said Executive Producer Jack Lane. “There is no better way to christen our new home at The Ross Family Theatre and welcome our audience back than with the return of ALWAYS… PATSY CLINE; the groundbreaking A CHORUS LINE; and the STAGES premiere of one of the most popular musicals in Broadway history, JERSEY BOYS.” STAGES is also overjoyed to welcome American Idol alum and Broadway star Diana DeGarmo as Patsy Cline, alongside STAGES-favorite Zoe Vonder Haar as Louise Seger in the encore of the bestselling production in STAGES’ history, ALWAYS… PATSY CLINE. -

DRAMATURGY GUIDE School of Rock: the Musical the National Theatre January 16-27, 2019

DRAMATURGY GUIDE School of Rock: The Musical The National Theatre January 16-27, 2019 Music by Andrew Lloyd Webber Book by Julian Fellowes Lyrics by Glenn Slater Based on the Paramount Film Written by Mike White Featuring 14 new songs from Andrew Lloyd Webber and all the original songs from the movie Packet prepared by Dramaturg Linda Lombardi Sources: School of Rock: The Musical, The Washington Post ABOUT THE SHOW Based on the hit film, this hilarious new musical follows Dewey Finn, a failed, wannabe rock star who poses as a substitute teacher at a prestigious prep school to earn a few extra bucks. To live out his dream of winning the Battle of the Bands, he turns a class of straight-A students into a guitar-shredding, bass-slapping, mind-blowing rock band. While teaching the students what it means to truly rock, something happens Dewey didn’t expect... they teach him what it means to care about something other than yourself. For almost 200 years, The National Theatre has occupied a prominent position on Pennsylvania Avenue – “America’s Main Street” – and played a central role in the cultural and civic life of Washington, DC. Located a stone’s throw from the White House and having the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site as it’s “front yard,” The National Theatre is a historic, cultural presence in our Nation’s Capital and the oldest continuously operating enterprise on Pennsylvania Avenue. The non-profit National Theatre Corporation oversees the historic theatre and serves the DC community through three free outreach programs, Saturday Morning at The National, Community Stage Connections, and the High School Ticket Program. -

Hair: the Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960S’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Winchester Research Repository University of Winchester ‘Hair: The Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960s’ Sarah Elisabeth Browne ORCID: 0000-0003-2002-9794 Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester MPhil/PhD THESES OPEN ACCESS / EMBARGO AGREEMENT FORM This Agreement should be completed, signed and bound with the hard copy of the thesis and also included in the e-copy. (see Thesis Presentation Guidelines for details). Access Permissions and Transfer of Non-Exclusive Rights By giving permission you understand that your thesis will be accessible to a wide variety of people and institutions – including automated agents – via the World Wide Web and that an electronic copy of your thesis may also be included in the British Library Electronic Theses On-line System (EThOS). Once the Work is deposited, a citation to the Work will always remain visible. Removal of the Work can be made after discussion with the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, who shall make best efforts to ensure removal of the Work from any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement. Agreement: I understand that the thesis listed on this form will be deposited in the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, and by giving permission to the University of Winchester to make my thesis publically available I agree that the: • University of Winchester’s Research Repository administrators or any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement to do so may, without changing content, translate the Work to any medium or format for the purpose of future preservation and accessibility. -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

Download Program Notes

PROGRAM: SONDHEIM SONGBOOK MAY 20 / 7:30 PM BING CONCERT HALL ARTISTS PROGRAM Betsy Wolfe, vocals Love Is in the Air (Ted, Betsy, Clarke) Clarke Thorell, vocals Love I Hear (Clarke) Paul Masse, piano What More Do I Need? (Betsy) Ted Sperling, music director and piano Barcelona (Clarke, Betsy) Moments in the Woods (Betsy) What Can You Lose? (Clarke) We gratefully acknowledge the generous support The Girls of Summer (Betsy) of Bonnie and Marty Tenenbaum. Honey (Clarke, Betsy) Getting Married Today (Ted, Clarke, Betsy) Pleasant Little Kingdom/Too Many Mornings (Clarke, Betsy) INTERMISSION By the Sea (Betsy, Clarke) Not a Day Goes By (Betsy) Good Thing Going (Ted) Buddy’s Blues (Clarke) Could I Leave You? (Betsy) A Little House for Mama (Clarke) Children Will Listen (Betsy) Finishing the Hat (Clarke) There Won’t Be Trumpets (Betsy) It Takes Two (Betsy, Clarke) PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE. Please be considerate of others and turn off all phones, pagers, and watch alarms, and unwrap all lozenges prior to the performance. Photography and recording of any kind are not permitted. Thank you. 26 STANFORD LIVE MAGAZINE MAY/JUNE 2015 He has gone from cult figure to national with the New York Philharmonic and The icon. His melodies, which have been labeled King and I at the Lincoln Center Theater. “unhummable,” get under your skin and linger for days. He is perhaps the greatest English- In the opera world, Mr. Sperling has language lyricist of any age. Every brilliant conducted The Mikado, Song of Norway, lyric and crystalline melody will be audible and Ricky Gordon’s The Grapes of Wrath in Bing Concert Hall when Ted Sperling, at Carnegie Hall; Kurt Weill’s The Firebrand one of Broadway’s most in-demand music of Florence at Alice Tully Hall; and a double directors, is joined at the piano by Betsy bill for the Houston Grand Opera and Wolfe and Clarke Thorell, two of Broadway’s Audra McDonald: La voix humaine by freshest singers. -

To Register for Your Audition

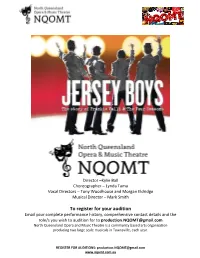

Director –Kylie Ball Choreographer – Lynda Tama Vocal Directors – Tony Woodhouse and Morgan Eldridge Musical Director – Mark Smith To register for your audition Email your complete performance history, comprehensive contact details and the role/s you wish to audition for to [email protected] North Queensland Opera and Music Theatre is a community based arts organisation producing two large scale musicals in Townsville, each year. REGISTER FOR AUDITIONS: [email protected] www.nqomt.com.au Production Details Information Night Sunday 1st November two sessions at 6.00pm and 7.00pm at NQOMT Hall, Gill Park, Pimlico Come and chat to the production team, find out how you can be involved, ask questions, book an audition. Please note that bookings for a place at the information session is vital. Due to Covid-19 restrictions we will be restricting the number of people in the hall so without a booking you may not gain entry. Book a place with the production manager – [email protected] Auditions Saturday 14th November 2020 - Vocal auditions Sunday 15th November 2020 – 1pm to 5pm Dance auditions Monday 16th November after 7pm - Call backs All held at NQOMT Hall, Gill Park, Pimlico Performances Wednesday 17th March 2021 – Saturday 27th March 2021 Civic Theatre, Boundary Street, Townsville Rehearsals All Sundays (1-6pm) – All cast All Mondays (7.00-10pm) – All cast All Wednesdays (7.00-10pm) – All cast Fridays (7.00-10pm) – These rehearsals will take place closer to the show dates and as per the Director’s request in consultation with required cast members. Rehearsals will start January 2021, male leads start on the 29th November 2020.