Metaphors and Gestures in Music Teaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao's Piano Concerto, Op. 53

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao’s Piano Concerto, Op. 53: A Comparison with Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lin-Min Chang, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven Glaser, Advisor Dr. Anna Gowboy Dr. Kia-Hui Tan Copyright by Lin-Min Chang 2018 2 ABSTRACT One of the most prominent Taiwanese composers, Tyzen Hsiao, is known as the “Sergei Rachmaninoff of Taiwan.” The primary purpose of this document is to compare and discuss his Piano Concerto Op. 53, from a performer’s perspective, with the Second Piano Concerto of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Hsiao’s preferences of musical materials such as harmony, texture, and rhythmic patterns are influenced by Romantic, Impressionist, and 20th century musicians incorporating these elements together with Taiwanese folk song into a unique musical style. This document consists of four chapters. The first chapter introduces Hsiao’s biography and his musical style; the second chapter focuses on analyzing Hsiao’s Piano Concerto Op. 53 in C minor from a performer’s perspective; the third chapter is a comparison of Hsiao and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos regarding the similarities of orchestration and structure, rhythm and technique, phrasing and articulation, harmony and texture. The chapter also covers the differences in the function of the cadenza, and the interaction between solo piano and orchestra; and the final chapter provides some performance suggestions to the practical issues in regard to phrasing, voicing, technique, color, pedaling, and articulation of Hsiao’s Piano Concerto from the perspective of a pianist. -

Selected Taiwanese Art Songs of Hsiao Tyzen

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Selected Taiwanses Art Songs of Hsiao Tyzen Hui-Ting Yang Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC SELECTED TAIWANESE ART SONGS OF HSIAO TYZEN By HUI-TING YANG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Hui-Ting Yang All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Hui-Ting Yang defended on April 28, 2006. __________________________ Timothy Hoekman Professor Directing Treatise __________________________ Ladislav Kubik Outside Committee Member __________________________ Carolyn Bridger Committee Member __________________________ Valerie Trujillo Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii Dedicated to my parents, Mr. Yang Fu-Hsiang (GJI) and Mrs. Hsieh Chu-Leng (HF!), and my uncle, Mr. Yang Fu-Chih (GJE) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks go to my treatise committee members, not only for their suggestions and interest in this treatise but also for their support and encouragement during all the working process. My great admiration goes to my treatise director, Dr. Timothy Hoekman, who spent endless hours reading my paper and making corrections for me, giving me inspiring ideas during each discussion. My special thanks go to my major professor, Dr. Carolyn Bridger, who offered me guidance, advice, and continuous warm support throughout my entire doctoral studies. I am thankful for her understanding and listening to my heart. -

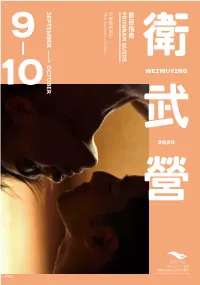

Sep Tember Oc Tober

SEPTEMBER PROGRAM GUIDE The Journey of love of Journey The 9 OCTOBER 10 WEIWUYING 2020 © 1 Contents 004 9 September Program Calender 006 10 October Program Calender 010 Feature 014 9 September Programs 036 10 October Programs 079 Exhibition 080 Activity Opening Hours 104 Tour Service 11:00-21:00 105 Become Our Valued Friend Service Center (Box Office) 106 Visit Us 11:00-21:00 For more information weiwuying_centerforthearts @weiwuying @weiwuying_tw COVID-19 National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts (Weiwuying) Preventive Measures against the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Epidemic Please follow the policies below before entering the venue A Special Plan for Performers 60 Performers can get a full refund for the rent if cancel the show 60 days before the scheduled date. Technical tests and rehearsals require no fee. 50% Rents are 50% off in the following situations: Audience are required to sit at intervals. / Live shows are changed into online streaming or recorded videos. / First-time auditorium rental for online streaming or video recording First-time auditorium rental for technical tests and rehearsals If you change the auditorium reservation from the original one into a larger one, the prices remain unchanged. Please contact us for the following ticketing matters. For the shows cancelled with a purpose of pandemic prevention, domestic performance teams have the priority to schedule the time in the second half of 2020 and the first half of 2021. Weiwuying will keep updating this special plan according to National Health Command Center policies. Weiwuying will work together with the public in preventing the spread of the epidemic and building a comfortable and safe venue. -

Musical Taiwan Under Japanese Colonial Rule: a Historical and Ethnomusicological Interpretation

MUSICAL TAIWAN UNDER JAPANESE COLONIAL RULE: A HISTORICAL AND ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION by Hui‐Hsuan Chao A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, Chair Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Jennifer E. Robertson Associate Professor Amy K. Stillman © Hui‐Hsuan Chao 2009 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout my years as a graduate student at the University of Michigan, I have been grateful to have the support of professors, colleagues, friends, and family. My committee chair and mentor, Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, generously offered his time, advice, encouragement, insightful comments and constructive criticism to shepherd me through each phase of this project. I am indebted to my dissertation committee, Professors Judith Becker, Jennifer Robertson, and Amy Ku’uleialoha Stillman, who have provided me invaluable encouragement and continual inspiration through their scholarly integrity and intellectual curiosity. I must acknowledge special gratitude to Professor Emeritus Richard Crawford, whose vast knowledge in American music and unparallel scholarship in American music historiography opened my ears and inspired me to explore similar issues in my area of interest. The inquiry led to the beginning of this dissertation project. Special thanks go to friends at AABS and LBA, who have tirelessly provided precious opportunities that helped me to learn how to maintain balance and wellness in life. ii Many individuals and institutions came to my aid during the years of this project. I am fortunate to have the friendship and mentorship from Professor Nancy Guy of University of California, San Diego. -

Asian Pacific American Heritage Month 2021 Calendar and Cultural Guide

ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH 2021 CALENDAR AND CULTURAL GUIDE PRESENTED BY THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH UNITE. EMPOWER. RISE. CITY OF LOS ANGELES LOS ANGELES CITY COUNCIL CULTURAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION Eric Garcetti Nury Martinez John Wirfs, President Mayor Los Angeles City Council President Elissa Scrafano, Vice President City of Los Angeles Councilwoman, Sixth District Evonne Gallardo Mike Feuer Gilbert Cedillo, District 1 Thien Ho Los Angeles City Attorney Paul Krekorian, District 2 Ron Galperin Charmaine Jefferson Bob Blumenfield, District 3 Los Angeles City Controller Eric Paquette Nithya Raman, District 4 Robert Vinson Paul Koretz, District 5 Monica Rodriguez, District 7 CITY OF LOS ANGELES Marqueece Harris-Dawson, DEPARTMENT OF District 8 CULTURAL AFFAIRS Curren D. Price, Jr., District 9 Danielle Brazell Mark Ridley-Thomas, District 10 General Manager Mike Bonin, District 11 Daniel Tarica Assistant General Manager John S. Lee, District 12 Will Caperton y Montoya Mitch O’Farrell, District 13 Director of Marketing, Development, Kevin de Leon, District 14 and Design Strategy Joe Buscaino, District 15 CALENDAR PRODUCTION Will Caperton y Montoya Editor and Art Director Marcia Harris Whitley Company CALENDAR DESIGN Whitley Company Front and back cover: Maria Kane, front: Green Spring, Acrylic on canvas, 19” x 12.5”, 2020, back: The Tiger, Acrylic on canvas, 17” x 7.5”, 2021 ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH CELEBRATION. ERIC GARCETTI MAYOR CITY OF LOS ANGELES Dear Friends, On behalf of the City of Los Angeles, it is my pleasure to join all Angelenos in celebrating Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. -

Music and National Identity: a Study of Cello Works by Taiwanese Composers

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Music and National Identity: A Study of Cello Works by Taiwanese Composers Yu-Ting Wu Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1740 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MUSIC AND NATIONAL IDENTITY A STUDY OF CELLO WORKS BY TAIWANESE COMPOSERS BY YU-TING WU A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY IN MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS, THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK 2010 ii © 2010 YU-TING WU All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Prof. David Olan Date Chair of Examining Committee Prof. Norman Carey Date Executive Officer Prof. Philip Rupprecht Prof. Peter Basquin Prof. John Graziano Supervision Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT MUSIC AND NATIONAL IDENTITY A STUDY OF CELLO WORKS BY TAIWANESE COMPOSERS by Yu-Ting Wu Adviser: Professor Philip Rupprecht The purpose of this study is to explore the impact of folkloric elements in music by Taiwanese composers and to uncover the methods they treat regional materials under the influences of Western compositional techniques, hereby creating a new fusion within classical music. -

Taiwanese Composer Tyzen Hsiao: Pedagogical Aspects of Selected Piano Solo Works

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 Taiwanese Composer Tyzen Hsiao: Pedagogical Aspects of Selected Piano Solo Works Tzu-Nung Lin Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lin, Tzu-Nung, "Taiwanese Composer Tyzen Hsiao: Pedagogical Aspects of Selected Piano Solo Works" (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6092. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6092 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taiwanese Composer Tyzen Hsiao: Pedagogical Aspects of Selected Piano Solo Works Tzu-Nung Lin Research Document submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance Peter Amstutz, D.M.A., Committee Chair and Research Advisor William -

Encyclopedia Taiw Anese a M Erican

Encyclopedia Taiwanese American Taiwanese Encyclopedia Our Journeys (1) 1 Encyclopedia Taiwanese American Our Journeys 2 Table of Contents The First Action: The Birth of the Taiwan Center Building Committee ................................ 7 Author: Patrick Huang .............................................................................................................................. 7 New York Taiwan Center: Rebirth in the Midst of Hardship................................................ 10 Author: Chia-lung Cheng ........................................................................................................................ 10 Longing for a Place – The Early Years of the New York Taiwan Center ............................. 12 Author: Chao-ping Huang ....................................................................................................................... 12 A Brief Introduction to the Taiwanese Community Center in Houston, Texas.................... 15 Compiled by the Taiwanese Heritage Society of Houston ..................................................................... 15 Tenth Anniversary of the Taiwanese Community Center’s Opening.................................... 17 Author: Cheng Y. Eddie Chuang ............................................................................................................ 17 The Early Life and Transformation of the San Diego Taiwan Center .................................. 26 Author: Cheng-yuan Huang ................................................................................................................... -

Artist in Residence Joanne Chang, Piano

Department of Music College of Fine Arts presents a Artist In Residence Joanne Chang, piano PROGRAM Tyzen Hsiao Toccata, Op. 57 (1990- 1995) (b. 1938) Hsin Jung Tsai Precipitation (20 11) (b. 1970) Zhang Zhao Pi Huang- Moments in Beijing Opera (1995) (b. 1960) Tan Dun Eight Memories in Water Color (1978) (b. 1957) I. Missing Moon II. Staccato Beans Ill. Herdboy's Song IV. BlueNun V. Red Wilderness VI. Ancient Burial VII. Floating Clouds VIII. Sunrain INTERMISSION Davide Zannoni Flexible Desire (20 11) (b. 1958) Maurice Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917) (1875 -1937) I. Prelude II. Fugue lll.Forlane IV.Riguadon V. Menuet VI. Toccata Tuesday, November 15, 2011 7:30p.m. Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall Lee and Thomas Beam Music Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas Joanne Chang, Ed.D. The New York-based classical pianist has performed extensively worldwide on five continents as a recitalist, soloist with orchestras, and in various chamber music ensembles. In 1995, she gave her recital debut in Australia, and subsequently performed at Die Stiftung Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival in Germany, and at Carnegie Weill Hall in New York City. Joanne came to the prominence when she was the Second-Prize winner in the National Taiwan Piano Competition and a string prize winner for National Taiwan Viola Competition. Continuing her study in Australia, Joanne was awarded a four-year scholarship towards her Bachelor's degree in Australia, where she graduated valedictorian and received a special honor. She has been awarded many scholarships and prizes: The President Award, Piano Workshop Award, First-Prize of Yamaha Keyboard Scholarship, Kerrison Piano Scholarship, and two times Queensland Piano Foundation Scholarship Award to name a few. -

Cultural Identity and Ethnic Representation in Arts Education: Case Studies of Taiwanese Festivals in Canada

CULTURAL IDENTITY AND ETHNIC REPRESENTATION IN ARTS EDUCATION: CASE STUDIES OF TAIWANESE FESTIVALS IN CANADA by PATRICIA YUEN-WAN LIN B.A., National Cheng-Chi University, Taiwan, 1985 M.A., University of Kansas, U.S.A., 1991 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Curriculum Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May 2000 © Patricia Yuen-Wan Lin, 2000 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. 1 further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Caff?M^/f/./y>t. fyj/fifrfiA The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) Abstract This study is about why and how Taiwanese immigrants construct their cultural identity through public festivals within Canadian multicultural society. The study stems from intrigue with prevailing practices in art education, both those characterizing Chinese as a homogeneous ethnic group and those viewing Chinese culture as a static tradition. Analyzing cultural representation organized by the Taiwanese community, I argue that ethnic cultural festivals are not only a site where immigrants inquire into cultural identity, but also a creative response to the receiving society's social context. -

Outstanding Taiwanese Americans

Encyclopedia Taiwanese Encyclopedia American O.T.A. () Encyclopedia Taiwanese American 台美族百科全書 Outstanding Taiwanese Americans Preface For Outstanding Taiwanese American Starting in 1950, Taiwanese for a variety of different reasons traveled across the sea to start a new life in America. In the beginning, the majority of Taiwanese immigrants were college graduates. Because job opportunities in Taiwan were lacking, and because they wanted to pursue an advanced education at a time when Taiwan did not have many graduate schools, these students chose to go abroad. At the time, a lot of American science and engineering graduate programs were offering scholarships to international students, and as a result, many students applied to come to the United States in order to advance their academic careers. Back then, there was a shortage of medical personnel in America, and thus foreign doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals were being recruited. At the same time, Taiwan’s political and economic environment was looking rather bleak. These conditions encouraged many native Taiwanese medical professionals to leave for the United States. These students and medical professionals slowly began to put down roots, starting new lives and careers in this new country. Soon becoming American citizens, these two groups became the foundation of the current Taiwanese American community. In 1980, there was decreased political support for Taiwan within the international community, but the Taiwanese economy was beginning to take off. Because of this, many Taiwanese had the means to come to the States as family-based immigrants or business investors. These people constituted the third wave of Taiwanese immigrants to the United States. -

Youth Orchestra, Cycny Annual Concert at Lincoln Center 2015

05-16 CYCNY_GP 4/27/15 11:47 AM Page 1 Saturday Evening, May 16, 2015, at 8:00 YOUTH ORCHESTRA, CYCNY ANNUAL CONCERT AT LINCOLN CENTER 2015 CHIJEN CHRISTOPHER CHUNG, Music Director & Conductor LOVELL PARK CHANG , Trumpet Soloist MIKHAIL GLINKA Ruslan and Ludmila Overture MAURICE RAVEL Pavane pour une infante défunte FU-TONG WONG Symphony Condor Heroes (U.S. Premiere) VII. Dance JOSEPH HAYDN Trumpet Concerto in E-flat major I. Allegro II. Andante cantabile III. Allegro LOVELL PARK CHANG , Trumpet Solo Intermission AARON COPLAND Hoe-Down from Rodeo TYZEN HSIAO The Angel from Formosa KRISTEN ANDERSON-LOPEZ AND ROBERT LOPEZ Music from Frozen arr. by Bob Krogstad GEORGES BIZET Carmen Suite No. 2 I. Habanera VI. Dance Bohème This concert is supported in part, by the public funds from the New York City Department Of Cultural Affairs. Alice Tully Hall Please make certain your cellular phone, pager, or watch alarm is switched off. 05-16 CYCNY_GP 4/27/15 11:47 AM Page 2 Lincoln Center Meet the Artists summer, the Orchestra will travel to Tokyo and Taipei for concerts and sightseeing. Our program is sponsored, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs. Other sponsors include Culture Center & Taipei Cultural Center of Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in New York, as well as foundations, corporations, and individuals. For more information, please visit www.YouthOrchestra.com , e-mail: The Youth Orchestra is a Queens-based [email protected] , or call ( 917 ) 912- 8288 Youth Orchestra since 1996, and has been or ( 347 ) 306-2511.