Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of a Shaker Bible

Inspiration, Revelation, and Scripture: The Story of a Shaker Bible STEPHEN J. STEIN OR MORE than two hundred years the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, a religious commu- Fnity commonly known as the Shakers, has been involved with publishing. In 1790 'the first printed statement of Shaker theology' appeared anonymously in Bennington, Vermont, under the imprint of 'Haswell & Russell." Entitied A Concise Statement of the Principles of the Only True Church, according to the Gospel of the Present Appearance of Christ, this publication marked a departure from the pattern established by the founder, Ann Lee, an Englishwoman who came to America in 1774. Lee, herself illiter- ate, feared fixed statements of behef, and forbade her followers to write such documents. Within the space of two decades, however, the Shakers rejected Lee's counsel and turned with increasing fre- quency to the printing press in order to defend themselves against Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the Museum of Our National Heritage, Lexington, Massachusetts (1993), at the annual meeting of the American Society of Church History in San Erancisco (1994), and at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio (1995), under the auspices of the Arthur C. Wickenden Memorial Lectureship. My special thanlcs to Jerry Grant, who shared some of his research notes dealing with the Sacred Roll, which I have used in this version of the essay. I. See Mary L. Richmond, Shaker Literature: A Bibliography (2 vols., Hancock, Mass.: Shaker Community, Inc., 1977), i: 145-46. Richmond echoes the common judgment con- cerning the authorship of this tract, attributing it to Joseph Meacham, an early American convert to Shakerism. -

“The Great Dreams Pass On” Phyllis Webb’S “Struggles of Silence”

Laura Cameron “The Great Dreams Pass On” Phyllis Webb’s “Struggles of Silence” “My poems are born out of great struggles of silence,” wrote Phyllis Webb in the Foreword to her 198 volume, Wilson’s Bowl; “This book has been long in coming. Wayward, natural and unnatural silences, my desire for privacy, my critical hesitations, my critical wounds, my dissatisfactions with myself and the work have all contributed to a strange gestation” (9).1 In this frequently cited passage, Webb is referring to the fifteen-year publication gap that divides her forty-year career as a poet. She put out two full volumes before Naked Poems in 1965 and two full volumes after Wilson’s Bowl in 198, but in the interim she produced only a handful of poems that she judged publishable.2 And yet, although it might have appeared from the outside in this period as though Webb had renounced poetry for good, archival evidence—numerous poem drafts in various states of completion, grant applications outlining the projects that she intended to pursue, and radio scripts elaborating on her creative efforts and ideas— reveals that this was not simply a period of absence or withdrawal. On the contrary, the middle years of Webb’s career, her “struggles of silence,” were fertile, eventually fruitful, and integral to her poetic development. The interval was characterized by “dissatisfactions” and “hesitations,” as Webb says, but also—and just as importantly—by ambition and an intense desire to grow and progress as a poet, to expand her vision and to write poetry, as she described it, of “cosmic proportions.”3 The creation of Wilson’s Bowl was “a strange gestation” because Webb’s “progeny” did not mature as expected: Wilson’s Bowl was not the volume that she had initially set out to write. -

Eli Mandel Fonds (MSS 18)

University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections Finding Aid - Eli Mandel fonds (MSS 18) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.1 Printed: April 26, 2019 Language of description: English University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections 330 Elizabeth Dafoe Library Winnipeg Manitoba Canada R3T 2N2 Telephone: 204-474-9986 Fax: 204-474-7913 Email: [email protected] http://umanitoba.ca/libraries/archives/ http://umlarchives.lib.umanitoba.ca/index.php/eli-mandel-fonds Eli Mandel fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

FLYWAY a Long Poem

FLYWAY A Long Poem A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Writing In the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By SARAH ENS © Copyright Sarah Ens, August 2020. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an MFA in Writing degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make its Preliminary Pages freely available for inspection as outlined in the MFA in Writing Thesis License/Access Agreement accepted by the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in June 2013. Requests for permission to make use of material beyond the Preliminary Pages of this thesis should be addressed to the author of the thesis, or: Coordinator, MFA in Writing University of Saskatchewan Department of English Arts Building, Room 319 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan 116 Thorvaldson Building, 110 Science Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5C9 Canada i ABSTRACT Flyway is a long-poem articulation of home set within the Canadian landscape and told through the lens of forced migration and its corollary of trauma. Tracing the trajectory of the Russian Mennonite diaspora, Flyway examines how intergenerational upheaval generates anxieties of place which are mirrored in the human-disrupted migratory patterns of the natural world. Drawing from the rich tradition of the Canadian long poem, from my roots as a third-generation Mennonite immigrant, from eco-poetics, and from ecological research into the impact of climate change on the endangered landscape of Manitoba’s tallgrass prairie, Flyway migrates along geographical, psychological, and affective routes in an attempt to understand complexities of home. -

VALID BAPTISM Advisory List Prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit

249 VALID BAPTISM Advisory list prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit African Methodist Episcopal Patriotic Chinese Catholics Amish Polish National Church Anglican (valid Confirmation too) Ancient Eastern Churches Presbyterians (Syrian-Antiochian, Coptic, Reformed Church Malabar-Syrian, Armenian, Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Ethiopian) Day Saints (since 2001 known as the Assembly of God Community of Christ) Baptists Society of Pius X Christian and Missionary Alliance (followers of Bishop Marcel Lefebvre) Church of Christ United Church of Canada Church of God United Church of Christ Church of the Brethren United Reformed Church of the Nazarene Uniting Church of Australia Congregational Church Waldesian Disciples of Christ Zion Eastern Orthodox Churches Episcopalians – Anglicans LOCAL DETROIT AREA COMMUNITIES Evangelical Abundant Word of Life Evangelical United Brethren Brightmoor Church Jansenists Detroit World Outreach Liberal Catholic Church Grace Chapel, Oakland Lutherans Kensington Community Methodists Mercy Rd. Church, Redford (Baptist) Metropolitan Community Church New Life Ministries, St. Clair Shores Old Catholic Church Northridge Church, Plymouth Old Roman Catholic Church DOUBTFUL BAPTISM….NEED TO INVESTIGATE EACH Adventists Moravian Lighthouse Worship Center Pentecostal Mennonite Seventh Day Adventists DO NOT CELEBRATE BAPTISM OR HAVE INVALID BAPTISM Amana Church Society National David Spiritual American Ethical Union Temple of Christ Church Union Apostolic -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

Th€ Living Mosaic

$1.2$ pw C0Py Autumn, ig6g TH€ LIVING MOSAIC Articles BY PHYLLIS GROSSKURTH, JOHN OWER, MAX DORSINVILLE, SUSAN JACKELj MARGARET MORRISS Special Feature COMPILED BY JOHN REEVES, WITH POEMS BY YAR SLAVUTYCH, HENRIKAS NAGYS, WALTER BAUER, Y. Y. SEGAL, ZOFJA BOHDANOWICZ, ROBERT ZEND, ARVED VDRLAID, INGRIDE VIKSNA, LUIGI ROMEO, PADRAIG BROIN Reviews BY RALPH G USTAFSON , WARREN TALLMAN, JACK WARWICK, GEORGE BOWERING, DOUGLAS BARBOUR, VI C T O R HOAR, K E AT H F R ASE R , CLARA THOMAS, G AR Y GEDDES, ANN SADDLEMYER, G E O R G E WO O D C O C K , YAR SLAVUTYCH, W. F. HALL A QUARTERLY OF CRITICISM AND R6VI6W AN ABSENCE OF UTOPIAS LIITERATURES are defined as much by their lacks as by their abundances, and it is obviously significant that in the whole of Canadian writing there has appeared only one Utopian novel of any real interest; it is significant in terms of our society as much as of our literature. The book in question is A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder. It was written in the 1870's and published in 1888, eight years after the death of its author, James de Mille, a professor of English at Dalhousie, who combined teach- ing with the compulsive production of popular novels ; by the time of his death at the age of 46 he had already thirty volumes to his credit, but only A Strange Manuscript has any lasting interest. It has been revived as one of the reprints in the New Canadian Library (McClelland & Stewart, $2.75), with an introduction by R. -

PILLS. Certain of the De- RADWATS PILLS Dta for He Left a Very Fortunu to His Fire Sons, Deer of Divorce, from Ber Haiband, the DR

& MKDICIXES. MERCHANDISE, &u. Productloa of Beetroot Sujrnr lions of Minister and those of Deputy will MEKCtlANDlSE, &0. SUGA1! & MOLASSES. LEGAL NOTICES. In CierBiuay. establish between the Chamber and my Government; the presence of all the Min- X880 H&-waii- an SOMETHING WORTH READING! isters in the Chamber ; the deliberation in Itiao Suprome Court of the I "When at Cologne, we were told that the Council of affairs ; a un- R,K SLB 33L Air. State sincere JUST RECEIVED Islands. the late Joest had th merit of derstanding with will consti- the Erst minafictory for the the majority, EX tute for the country all the guarantees Kuhllanl. ts. Usury O. Tarks Divorce. re&ninar of foreign sorars, and afterwards v fn. which we seek iu our common solicitude. CompIniBMBt CASTLE & COOKE for the extraction of ssgar from tho bcot- - 1869 W1IK11B.VS, the la I have already proved several times how 2L Wood, entitled cause, bas filed a u W. root, anu reamng uie suptr uuuian. disposed I was." for tho public interest, to petition unto the Honorable A. S. llartwell, ARE business had proved so lucrative that l"he renounce my prerogatives. FROM BREMEN, Jnitlce of tho Supreme Court, praying for a PILLS. certain of The De- RADWATS PILLS Dta For he left a very fortunu to his fire sons, deer of divorce, from ber haiband, the DR. hrp modifications which have decided to pro- A Large Merchan- Stocaacb, Bowels, and 3"oxj3t which them individually several I and Varied Assortment of fendant aforesaid, on the grounds of willful EKiMif the Littr. -

The Origins of Millerite Separatism

The Origins of Millerite Separatism By Andrew Taylor (BA in History, Aurora University and MA in History, University of Rhode Island) CHAPTER 1 HISTORIANS AND MILLERITE SEPARATISM ===================================== Early in 1841, Truman Hendryx moved to Bradford, Pennsylvania, where he quickly grew alienated from his local church. Upon settling down in his new home, Hendryx attended several services in his new community’s Baptist church. After only a handful of visits, though, he became convinced that the church did not believe in what he referred to as “Bible religion.” Its “impiety” led him to lament, “I sometimes almost feel to use the language [of] the Prophecy ‘Lord, they have killed thy prophets and digged [sic] down thine [sic] altars and I only am left alone and they seek my life.”’1 His opposition to the church left him isolated in his community, but his fear of “degeneracy in the churches and ministers” was greater than his loneliness. Self-righteously believing that his beliefs were the “Bible truth,” he resolved to remain apart from the Baptist church rather than attend and be corrupted by its “sinful” influence.2 The “sinful” church from which Hendryx separated himself was characteristic of mainstream antebellum evangelicalism. The tumultuous first decades of the nineteenth century had transformed the theological and institutional foundations of mainstream American Protestantism. During the colonial era, American Protestantism had been dominated by the Congregational, Presbyterian, and Anglican churches, which, for the most part, had remained committed to the theology of John Calvin. In Calvinism, God was envisioned as all-powerful, having predetermined both the course of history and the eternal destiny of all humans. -

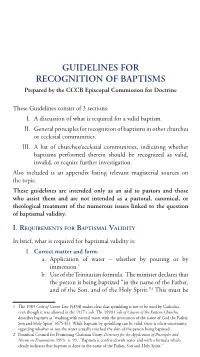

Guidelines for Recognition of Baptisms

First Church of Christ, Scientist Unitarian Universalist I (Mary Baker Eddy) - no baptism I Unitarians I Foursquare Gospel Church V United Church of Christ V General Assembly of Spiritualists I United Church of Canada V Hephzibah Faith Missionary Association I United Reformed V House of David Church I United Society of Believers I Iglesia ni Kristo (Phillippines) I Uniting Church in Australia V GUIDELINES FOR Independent Church of Filipino Christians I Universal Emancipation Church I RECOGNITION OF BAPTISMS Jehovah’s Witnesses (Watchtower Society) I Waldensian V Liberal Catholic Church V Worldwide Church of God (invalid before mid-1990’s) I Prepared by the CCCB Episcopal Commission for Doctrine Lutheran V Zion V Masons / Freemasons - no baptism I These Guidelines consist of 3 sections: Mennonite Churches ? I. A discussion of what is required for a valid baptism. APPENDIX: SOME MAGISTERIAL SOURCES TO BE CONSULTED Methodist V II. General principles for recognition of baptisms in other churches Metropolitan Community Church ? 1983 Code of Canon Law, n. 849-878. or ecclesial communities. Moonies (Reunification Church) I 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, n. 672-691. III. A list of churches/ecclesial communities, indicating whether Moravian Church ? Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity,Directory for the baptisms performed therein should be recognized as valid, National David Spiritual Temple of Christ Church Union I Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism, 1993, n. 92-101. invalid, or require further investigation. National Spiritualist Association I Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 1213-1284. Also included is an appendix listing relevant magisterial sources on The New Church I the topic. -

Origin and History of Seventh-Day Adventists, Vol. 1

Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists FRONTISPIECE PAINTING BY HARRY ANDERSON © 1949, BY REVIEW AND HERALD As the disciples watched their Master slowly disappear into heaven, they were solemnly reminded of His promise to come again, and of His commission to herald this good news to all the world. Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists VOLUME ONE by Arthur Whitefield Spalding REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. COPYRIGHT © 1961 BY THE REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. OFFSET IN THE U.S.A. AUTHOR'S FOREWORD TO FIRST EDITION THIS history, frankly, is written for "believers." The reader is assumed to have not only an interest but a communion. A writer on the history of any cause or group should have suffi- cient objectivity to relate his subject to its environment with- out distortion; but if he is to give life to it, he must be a con- frere. The general public, standing afar off, may desire more detachment in its author; but if it gets this, it gets it at the expense of vision, warmth, and life. There can be, indeed, no absolute objectivity in an expository historian. The painter and interpreter of any great movement must be in sympathy with the spirit and aim of that movement; it must be his cause. What he loses in equipoise he gains in momentum, and bal- ance is more a matter of drive than of teetering. This history of Seventh-day Adventists is written by one who is an Adventist, who believes in the message and mission of Adventists, and who would have everyone to be an Advent- ist. -

Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-16-2013 12:00 AM After Dark: Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age David S. Hickey The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. D.M.R. Bentley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © David S. Hickey 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hickey, David S., "After Dark: Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1805. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1805 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. After Dark: Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age Monograph by David Hickey Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Hickey 2013 i Abstract A threat to nocturnal ecosystems and human health alike, light pollution is an unnecessary problem that comes at an enormous cost. The International Dark-Sky Association has recently estimated that the energy expended on light scatter alone is responsible for no less than twelve million tons of carbon dioxide and costs municipal governments at least $1 billion annually (“Economic Issues” 2).