State-Building, Conquest, and Royal Sovereignty in Prussia, – *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communal Commercial Check City of Aachen

Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Communal commercial check City of Aachen Location Commune Aachen (Code: 5334002) Location Aachen (PLZ: 52062) (FPRE: DE-05-000334) Commune type City District Städteregion Aachen District type District Federal state North Rhine-Westphalia Topics 1 Labour market 9 Accessibility and infrastructure 2 Key figures: Economy 10 Perspectives 2030 3 Branch structure and structural change 4 Key branches 5 Branch division comparison 6 Population 7 Taxes, income and purchasing power 8 Market rents and price levels Fahrländer Partner AG Communal commercial check: City of Aachen 3rd quarter 2021 Raumentwicklung Eigentum von Fahrländer Partner AG, Zürich Summary Macro location text commerce City of Aachen Aachen (PLZ: 52062) lies in the City of Aachen in the District Städteregion Aachen in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Aachen has a population of 248'960 inhabitants (31.12.2019), living in 142'724 households. Thus, the average number of persons per household is 1.74. The yearly average net migration between 2014 and 2019 for Städteregion Aachen is 1'364 persons. In comparison to national numbers, average migration tendencies can be observed in Aachen within this time span. According to Fahrländer Partner (FPRE), in 2018 approximately 34.3% of the resident households on municipality level belong to the upper social class (Germany: 31.5%), 33.6% of the households belong to the middle class (Germany: 35.3%) and 32.0% to the lower social class (Germany: 33.2%). The yearly purchasing power per inhabitant in 2020 and on the communal level amounts to 22'591 EUR, at the federal state level North Rhine-Westphalia to 23'445 EUR and on national level to 23'766 EUR. -

Die Euregiobahn

Stolberg-Mühlener Bahnhof – Stolberg-Altstadt 2021 > Fahrplan Stolberg Hbf – Eschweiler-St. Jöris – Alsdorf – Herzogenrath – Aachen – Stolberg Hbf Eschweiler-Talbahnhof – Langerwehe – Düren Bahnhof/Haltepunkt Montag – Freitag Mo – Do Fr/Sa Stolberg Hbf ab 5:11 6:12 7:12 8:12 18:12 19:12 20:12 21:12 22:12 23:12 23:12 usw. x Eschweiler-St. Jöris ab 5:18 6:19 7:19 8:19 18:19 19:19 20:19 21:19 22:19 23:19 23:19 alle Alsdorf-Poststraße ab 5:20 6:21 7:21 8:21 18:21 19:21 20:21 21:21 22:21 23:21 23:21 60 Alsdorf-Mariadorf ab 5:22 6:23 7:23 8:23 18:23 19:23 20:23 21:23 22:23 23:23 23:23 Minu- x Alsdorf-Kellersberg ab 5:24 6:25 7:25 8:25 18:25 19:25 20:25 21:25 22:25 23:25 23:25 ten Alsdorf-Annapark an 5:26 6:27 7:27 8:27 18:27 19:27 20:27 21:27 22:27 23:27 23:27 Alsdorf-Annapark ab 5:31 6:02 6:32 7:02 7:32 8:02 8:32 9:02 18:32 19:02 19:32 20:02 20:32 21:02 21:32 22:02 22:32 23:32 23:32 Alsdorf-Busch ab 5:33 6:04 6:34 7:04 7:34 8:04 8:34 9:04 18:34 19:04 19:34 20:04 20:34 21:04 21:34 22:04 22:34 23:34 23:34 Herzogenrath-A.-Schm.-Platz ab 5:35 6:06 6:36 7:06 7:36 8:06 8:36 9:06 18:36 19:06 19:36 20:06 20:36 21:06 21:36 22:06 22:36 23:36 23:36 Herzogenrath-Alt-Merkstein ab 5:38 6:09 6:39 7:09 7:39 8:09 8:39 9:09 18:39 19:09 19:39 20:09 20:39 21:09 21:39 22:09 22:39 23:39 23:39 Herzogenrath ab 5:44 6:14 6:44 7:14 7:44 8:14 8:44 9:14 18:44 19:14 19:44 20:14 20:45 21:14 21:44 22:14 22:44 23:43 23:43 Kohlscheid ab 5:49 6:19 6:49 7:19 7:49 8:19 8:49 9:19 18:49 19:19 19:49 20:19 20:50 21:19 21:49 22:19 22:49 23:49 23:49 Aachen West ab 5:55 6:25 6:55 -

Family Businesses in Germany and the United States Since

Family Businesses in Germany and the United States since Industrialisation A Long-Term Historical Study Family Businesses in Germany and the United States since Industrialisation – A Long-Term Historical Study Industrialisation since States – A Long-Term the United and Businesses Germany in Family Publication details Published by: Stiftung Familienunternehmen Prinzregentenstraße 50 80538 Munich Germany Tel.: +49 (0) 89 / 12 76 400 02 Fax: +49 (0) 89 / 12 76 400 09 E-mail: [email protected] www.familienunternehmen.de Prepared by: Institut für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte Platz der Göttinger Sieben 5 37073 Göttingen Germany Univ.-Prof. Dr. Hartmut Berghoff Privatdozent Dr. Ingo Köhler © Stiftung Familienunternehmen, Munich 2019 Cover image: bibi57 | istock, Sasin Tipchai | shutterstock Reproduction is permitted provided the source is quoted ISBN: 978-3-942467-73-5 Quotation (full acknowledgement): Stiftung Familienunternehmen (eds.): Family Businesses in Germany and the United States since Indus- trialisation – A Long-Term Historical Study, by Prof. Dr. Hartmut Berghoff and PD Dr. Ingo Köhler, Munich 2019, www.familienunternehmen.de II Contents Summary of main results ........................................................................................................V A. Introduction. Current observations and historical questions ..............................................1 B. Long-term trends. Structural and institutional change ...................................................13 C. Inheritance law and the preservation -

Beratungs- Und Hilfsangebote Bei Trennund Und Scheidung

BERATUNGS- UND HILFSANGEBOTE bei Trennung Scheidung in Stadt und StädteRegion Aachen www.trennung-scheidung-aachen.de Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, Wir freuen uns, Ihnen die aktualisierte Neuauflage der Broschüre „Beratungs- und Hilfsangebote bei Trennung und Scheidung“ des Arbeitskreises Tren- nung/Scheidung Aachen vorstellen zu können. Sie finden in der Broschüre Anlauf- und Beratungs- stellen, bei denen Sie sich während einer Trennung oder Scheidung informieren können und Unterstüt- zung bekommen. Die Broschüre ist in verschiedene Themengebiete (Beratungsstellen allgemein, Hilfe für Alleinerzie- hende, Alleinerziehenden Gruppen in den Kirchen- gemeinden, Gruppen für Kinder in Trennung und Scheidung, Juristische Auskünfte/Rechtsberatung, Psychotherapeutische Hilfen, Meditation) unterteilt. Der erste Teil bezieht sich auf die Stadt Aachen, der zweite Teil auf Beratungsstellen und Hilfsangebote in der StädteRegion Aachen. Für den Arbeitskreis Trennung/Scheidung (Roswitha Damen) Gleichstellungsbeauftragte der Stadt Aachen Gleichstellungsbüro der Stadt Aachen 52058 Aachen Tel: 0241/432-7313 Fax: 0241/4135417999 Email: [email protected] www.aachen.de/gleichstellung Stadt Aachen Beratungsstelle der Arbeiterwohlfahrt (AWO) Gartenstr. 25 52064 Aachen Tel: 0241/889160 Email: [email protected] Diakonisches Werk im Kirchenkreis Aachen e.V. Familien- und Sozialberatung West Vaalser Str. 439 52074 Aachen Tel: 0241/989010 Fax: 0241/9890123 Email: [email protected] Donum Vitae e.V. Schwangerschaftskonfliktsberatung Franzstr. 109 52064 Aachen Tel: 0241/4009977 Fax: 0241/4009888 Email: [email protected] www.aachen.donumvitae.org Fachbereich ElternSchule Aachen – Familienbildung IN VIA Aachen e.V. Krefelder Str. 23 52070 Aachen Tel: 0241/6090815 Fax: 0241/6090820 Email: [email protected] www.elternschule-aachen.de Kath. Erziehungsberatungsstelle der Caritas Reumontstr. -

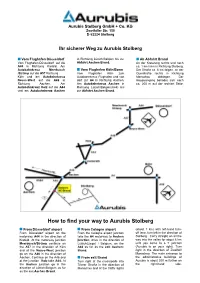

How to Find Your Way to Aurubis Stolberg

Aurubis Stolberg GmbH + Co. KG Zweifaller Str. 150 D-52224 Stolberg Ihr sicherer Weg zu Aurubis Stolberg Vom Flughafen Düsseldorf in Richtung Lüttich/Belgien bis zur Ab Abfahrt Brand Vom Flughafen Düsseldorf auf die Abfahrt Aachen-Brand. An der Kreuzung rechts und nach A44 in Richtung Krefeld. Am ca. 1 km links in Richtung Stolberg. Autobahnkreuz Meerbusch Vom Flughafen Köln/Bonn Der Straße ca. 6 km folgen, an der /Strümp auf die A57 Richtung Vom Flughafen Köln zum Querstraße rechts in Richtung Köln und am Autobahnkreuz Autobahnkreuz Flughafen und von Monschau abbiegen. Der Neuss-West auf die A46 in dort zur A4 in Richtung Aachen. Haupteingang befindet sich nach Richtung Aachen. Am Am Autobahnkreuz Aachen in ca. 200 m auf der rechten Seite. Autobahnkreuz Holz auf die A44 Richtung Lüttich/Belgien(A44) bis und am Autobahnkreuz Aachen zur Abfahrt Aachen-Brand. How to find your way to Aurubis Stolberg From Düsseldorf airport From Cologne airport (about 1 km) with left-hand turn- From Düsseldorf airport on the From the Cologne airport junction off lane, turn left in the direction of motorway A44 in the direction of take the A4 motorway to Aachen Stolberg . Carry straight on all the Krefeld. At the motorway junction junction, drive in the direction of way into the valley for about 6 km Meerbusch/Strümp continue on Lüttich(Liege) / Belgium, on the until you come to a T junction the A57 in the direction of Köln A44 as far as the exit Aachen- (Aurubis is on your right). Turn and at the Neuss-West jonction Brand. -

COMMISSION DECISION of 12 April 2006 Amending Decision 2003/135

13.4.2006EN Official Journal of the European Union L 104/51 COMMISSION DECISION of 12 April 2006 amending Decision 2003/135/EC as regards the extension of plans for the eradication and emergency vaccination of feral pigs against classical swine fever to certain areas of North Rhine- Westfalia and Rhineland-Palatinate and the termination of these plans in other areas of Rhineland- Palatinate (Germany) (notified under document number C(2006) 1531) (Only the German and French texts are authentic) (2006/285/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (3) Germany has also informed the Commission that the classical swine fever situation in certain areas of Rhineland-Palatinate has improved significantly and that Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European the plans for the eradication of classical swine fever and Community, emergency vaccination plans of feral pigs against classical swine fever no longer need to be applied in those areas. (4) Decision 2003/135/EC should therefore be amended Having regard to Council Directive 2001/89/EC of 23 October accordingly. 2001 on Community measures for the control of classical swine fever (1), and in particular Articles 16(1) and 20(2) thereof, (5) The measures provided for in this Decision are in accordance with the opinion of the Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health, Whereas: HAS ADOPTED THIS DECISION: Article 1 (1) Commission Decision 2003/135/EC of 27 February 2003 on the approval of the plans for the eradication The Annex to Decision 2003/135/EC is replaced by the text in of classical swine fever and the emergency vaccination of the Annex to this Decision. -

Mining in Central Europe Perspectives from Environmental History

Perspectives Mining in Central Europe Perspectives from Environmental History Edited by FRANK UEKOETTER 2012 / 10 RCC Perspectives Mining in Central Europe Perspectives from Environmental History Edited by Frank Uekoetter 2012 / 10 Mining in Central Europe 3 Contents 05 Introduction: Mining and the Environment Frank Uekoetter 07 Reconstructing the History of Copper and Silver Mining in Schwaz, Tirol Elisabeth Breitenlechner, Marina Hilber, Joachim Lutz, Yvonne Kathrein, Alois Unterkircher, and Klaus Oeggl 21 Mercurial Activity and Subterranean Landscapes: Towards an Environmental History of Mercury Mining in Early Modern Idrija Laura Hollsten 39 Ore Mining in the Sauerland District in Germany: Development of Industrial Mining in a Rural Setting Jan Ludwig 59 Ubiquitous Mining: The Spatial Patterns of Limestone Quarrying in Late Nineteenth-Century Rhineland Sebastian Haumann 71 Uranium Mining and the Environment in East and West Germany Manuel Schramm Mining in Central Europe 5 Frank Uekoetter Introduction: Mining and the Environment The mining exhibit is one of the most acclaimed parts of the Deutsches Museum. It sends visitors on a long, winding underground route that for the most part looks and feels like an actual mine. The exhibit casts a wide net: early modern mining, coal mining, lignite open-pit mining, and mining for ores and salt are all part of the tour, with ore processing and refining making for the grand finale. It is not an exhibit for the claustrophobic, as the path is rather narrow at times, and visitors are expected to complete the entire tour—there are only emergency exits between entrance and finish. However, most visitors enjoy the exhibit, and employees of the Deutsches Museum are accustomed to inquiries as to when they last took the tour. -

Infobroschüre

Informationsbroschüre für internationale Studierende 2020/21 Untertitel Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg Rechtswissenschaftliche Fakultät INCOMINGS Inhaltsverzeichnis (For English-version see English website) Das Auslandsbüro der Rechtswissenschaftlichen Fakultät 03 Herzlich Willkommen in Freiburg 04 Die Stadt Freiburg 05 Vorstellung der Universität und der Fakultät 07 Lageplan 12 Bewerbungsverfahren für Erasmus+ 13 Bewerbungs- und Zulassungsverfahren für LL.M.-Studierende 15 Wohnen in Freiburg 18 Sprachkurse am SLI (Sprachlehrinstitut) 20 Informationen zum Studium 22 Praktische Hinweise 25 Touristische Hinweise 31 Wichtige Adressen 32 2 Das Auslandsbüro der Rechtswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Herzlich Willkommen im Auslandsbüro Das Auslandsbüro der Rechtswissenschaftlichen Fakultät versteht sich als Dreh- und Angel- punkt für alle internationalen Angelegenheiten der Rechtswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Frei- burg. Internationale Studierende, Gäste und Dozenten – alle sind herzlich willkommen, mit ihren Fragen rund um das Studium in Freiburg an uns heranzutreten! Wir stehen in unseren Sprechstunden oder nach Vereinbarung gerne für alle Fragen zur Verfügung. Auch per E- Mail und Telefon. Kontakt: Auslandsbüro der Rechtswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg Erbprinzenstr. 17a, D-79085 Freiburg Tel: + 49 (0)761 203-2185 Fax: + 49 (0)761 203-5524 Mail: [email protected] www.jura.uni-freiburg.de/de/internationales 3 Herzlich willkommen in Freiburg und herzlich willkommen an der Rechtswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität! Wir freuen uns, Sie an der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg begrüßen zu dürfen! Mit dieser Broschüre wollen wir Ihnen einen möglichst einfachen und schnellen Start an der rechtswissenschaftlichen Fakultät ermöglichen. Wir stehen als Ansprechpartner für alle Fra- gen – besonders für Fragen zu Ihrem Studienplan – zur Verfügung. Hier vorab einige wichti- ge Informationen zum Studium in Freiburg: Das akademische Jahr wird in ein Winter- (01.10. -

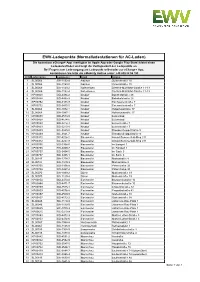

EWV-Ladepunkte (Normalladestationen Für AC-Laden)

EWV-Ladepunkte (Normalladestationen für AC-Laden) Die kostenlose eCharge+ App (verfügbar im Apple App oder Google Play Store) bietet einen Ladesäulenfinder und zeigt die Verfügbarkeit der Ladepunkte an. Bei Fragen zum Ladevorgang am Ladepunkt selbst oder zur eCharge+ App, kontaktieren Sie bitte die eMobility Hotline unter: +49 800 22 55 793 LFD Ladestation Ladepunkt Stadt Straße 1 SL00064 BA-1132-8 Aachen Zollernstraße 10 2 SL00064 BA-1153-0 Aachen Zollernstraße 10 3 SL00069 BA-1143-2 Aldenhoven Dietrich-Mühlfahrt-Straße 11-13 4 SL00069 BA-1152-4 Aldenhoven Dietrich-Mühlfahrt-Straße 11-13 5 KP00848 BD-4494-2 Alsdorf Bahnhofstraße 28 6 KP00848 BD-4495-9 Alsdorf Bahnhofstraße 28 7 KP00752 BD-3434-9 Alsdorf Eschweilerstraße 7 8 KP00752 BD-3435-5 Alsdorf Eschweilerstraße 7 9 SL00068 BA-1072-1 Alsdorf Hubertusstraße 17 10 SL00068 BA-1087-1 Alsdorf Hubertusstraße 17 11 KP00858 BD-4573-9 Alsdorf Luisenbad 12 KP00858 BD-4574-5 Alsdorf Luisenbad 13 KP00823 BD-3212-1 Alsdorf Luisenstraße 7 14 KP00823 BD-3213-8 Alsdorf Luisenstraße 7 15 KP00439 BC-3840-0 Alsdorf Theodor-Seipp-Straße 9 16 KP00439 BC-3841-7 Alsdorf Theodor-Seipp-Straße 9 17 KP00312 BC-4226-2 Baesweiler Arnold-Sommerfeld-Ring 211 18 KP00312 BC-4227-9 Baesweiler Arnold-Sommerfeld-Ring 211 19 KP00755 BD-3458-0 Baesweiler Im Bongert 1 20 KP00755 BD-3459-7 Baesweiler Im Bongert 1 21 KP00757 BD-3454-5 Baesweiler Im Sack 3 22 KP00757 BD-3455-1 Baesweiler Im Sack 3 23 SL00187 BA-1378-7 Baesweiler Mariastraße 8 24 SL00187 BA-1379-3 Baesweiler Mariastraße 8 25 KP00756 BD-3456-8 Baesweiler Peterstraße -

M1947 Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point, 1945–1952

M1947 RECORDS CONCERNING THE CENTRAL COLLECTING POINTS (“ARDELIA HALL COLLECTION”): WIESBADEN CENTRAL COLLECTING POINT, 1945–1952 National Archives and Records Administration Washington, DC 2008 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records concerning the central collecting points (“Ardelia Hall Collection”) : Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point, 1945–1952.— Washington, D.C. : National Archives and Records Administration, 2008. p. ; cm.-- (National Archives microfilm publications. Publications describing ; M 1947) Cover title. 1. Hall, Ardelia – Archives – Microform catalogs. 2. Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945–1955 : U.S. Zone). Office of Military Government. Property Division – Archives – Microform catalogs. 3. Restitution and indemnification claims (1933– ) – Germany – Microform catalogs. 4. World War, 1939–1945 – Confiscations and contributions – Germany – Archival resources – Microform catalogs. 5. Cultural property – Germany (West) – Archival resources – Microform catalogs. I. Title. INTRODUCTION On 117 rolls of this microfilm publication, M1947, are reproduced the administrative records, photographs of artworks, and property cards from the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point during the period 1945–52. The Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) Section recovered Nazi-looted works of art and artifacts from various storage areas and shipped the objects to one of four U.S. central collecting points, including Wiesbaden. In order to research restitution claims, MFAA officers gathered intelligence reports, interrogation reports, captured documents, and general information regarding German art looting. The Wiesbaden records are part of the “Ardelia Hall Collection” in Records of United States Occupation Headquarters, World War II, Record Group (RG) 260. BACKGROUND The basic authority for taking custody of property in Germany was contained in Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) Directive 1067/6, which directed the U.S. -

Important Safety Note

Medos Medizintechnik AG . Obere Steinfurt 8 - 10 . 52222 Stolberg. Germany Contact person: Fax: +49 7131 2706-299 E-Mail: [email protected] Heilbronn, 21. Mai 2021 Important safety note FSN21-02: Due to the increased complaints rate (trend) of pump head recently, Medos Medizintechnik AG recognized a potential risk of the product and thus decided to recall following products from the market. Affected Products: Tubing set for the organ perfusion Brand names Liver Assist-Set, Model Organ Perfusionset, Kidney net, Model Organ Assist Organ Assist Reference number MEH133411 MEH132909 Affected batch number 190220M146 190403M954 Quantity 18 48 Date: 21. May 2021 Reference number: FSN 21-02 Addressee: Reason: This letter means to inform you about the deficiency of the products. The products with above mentioned batch number include defective pump head and this could cause malfunction of the tubing set. Dear Mr. Due to the increased complaints regarding pump head DP2, the company Xenios recognize a potential risk of the product. The results of the complaints investigation shows the pump head was glued together and thus a non-rotating pump head. Description of the product deficiency The described pumphead problem is caused by deficiencies during the production phase. Medos Medizintechnik AG Management Board Registered Office Commerzbank Aachen Obere Steinfurt 8 - 10 Jörg Buschbell Stolberg (Rhineland) Konto 381 901 800 52222 Stolberg, Germany Stefan Kretzschmar County Court Aachen BLZ 390 400 13 [email protected] Jürgen O. Böhm, MD HRB 18349 IBAN www.xenios-ag.com T +49 7131 2706 0 DE11 3904 0013 0381 9018 00 F +49 7131 2706 299 Supervisory Board UST.Id.-Nr. -

Heinrich Von Treitschke| Creating a German National Mission

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2004 Heinrich von Treitschke| Creating a German national mission Johnathan Bruce Kilgour The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kilgour, Johnathan Bruce, "Heinrich von Treitschke| Creating a German national mission" (2004). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2530. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2530 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRAJR.Y The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission _ No, I do not grant permission _ Author's Signattre; Date: / 2 - / ^ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 HEINRICH VON TREITSCHKE; CREATING A GERMAN NATIONAL MISSION by Johnathan Bruce Kilgour B.A. Colhy College, 2001 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 2004 Approved hy: Chairperson Dean, Graduate School [*2.- 13 - 04- Date UMI Number: EP35706 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.