Evaluation of Real-Time Weather Map Discussions in the Middle School Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Maths

Summer Term Curriculum Overview for Year 5 2021 only Black-First half (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) Red- Second half (The Secret Garden) English Reading Comprehension Planning, Composing and Evaluating Maths Develop ideas through reading and research Grammar, Punctuation and Vocabulary Use a wide knowledge of text types, forms and styles to inform Check that the text makes sense to them and Fractions B (calculating) (4 weeks) Decimals and percentages (3 weeks) Decimals (5 weeks) their writing Use correct grammatical terminology when discuss their understanding discussing their writing Plan and write for a clear purpose and audience Use imagination and empathy to explore a text Ensure that the content and style of writing accurately reflects Decimals (5 weeks) Geometry: angles (just shape work, angles have been covered) Geometry: position and Use the suffixes –ate, -ise, and –ify to convert nouns beyond the page the purpose or adjectives into verbs Answer questions drawing on information from Borrow and adapt writers’ techniques from book, screen and direction Measurement: volume and converting units Understand what parenthesis is several places in the text stage Recognise and identify brackets and dashes Predict what may happen using stated and Balance narrative writing between action, description and dialogue Use brackets, dashes or commas for parenthesis implied details and a wider personal Geography Evaluate the work of others and suggest improvements Ensure correct subject verb agreement understanding of the world Evaluate their work effectively and make improvements based Name, locate and describe major world cities. Revisit: Identify the location and explain the Summarise using an appropriate amount of detail on this function of the Prime (or Greenwich) Meridian and different time zones (including day and History as evidence Proof–read for spelling and punctuation errors night). -

Years 3–4, and the Others in Years 5–6

Unit 16 What’s in the news? ABOUT THE UNIT This is a ‘continuous’ unit, designed to be developed at various points through the key stage. It shows how news items at a widening range of scales can be used to develop geographical skills and ideas. The unit can be used flexibly when relevant news events occur. The teaching ideas could be selected and used outside designated geography curriculum time, eg during assembly, a short activity at the beginning or end of the day, or within a context for literacy and mathematics work. Alternatively the ideas could be integrated within other geography units where appropriate, eg weather reports could be linked to work on weather and distant localities, see Unit 7. The first three sections are designed to be used in years 3–4, and the others in years 5–6. The unit offers links to literacy, mathematics, speaking and listening and IT. Widening range of scales Undertake fieldwork Wider context Use globes, maps School locality and atlases UK locality Use secondary sources Overseas locality Identify places on Physical and human features maps A, B and C Similarities and differences Use ICT Changes Weather: seasons, world weather Environment: impact Other aspects of skills, places and themes may be covered depending on the content of the news item. VOCABULARY RESOURCES In this unit, children are likely to use: • newspapers • news, current affairs, issues, weather, weather symbols, climate, country, • access to the internet continent, land use, environmental quality, community, physical features, human • local -

Print Key. (Pdf)

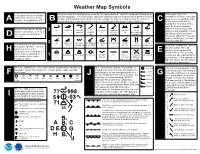

Weather Map Symbols Along the center, the cloud types are indicated. The top symbol is the high-level cloud type followed by the At the upper right is the In the upper left, the temperature mid-level cloud type. The lowest symbol represents low-level cloud over a number which tells the height of atmospheric pressure reduced to is plotted in Fahrenheit. In this the base of that cloud (in hundreds of feet) In this example, the high level cloud is Cirrus, the mid-level mean sea level in millibars (mb) A example, the temperature is 77°F. B C C to the nearest tenth with the cloud is Altocumulus and the low-level clouds is a cumulonimbus with a base height of 2000 feet. leading 9 or 10 omitted. In this case the pressure would be 999.8 mb. If the pressure was On the second row, the far-left Ci Dense Ci Ci 3 Dense Ci Cs below Cs above Overcast Cs not Cc plotted as 024 it would be 1002.4 number is the visibility in miles. In from Cb invading 45° 45°; not Cs ovcercast; not this example, the visibility is sky overcast increasing mb. When trying to determine D whether to add a 9 or 10 use the five miles. number that will give you a value closest to 1000 mb. 2 As Dense As Ac; semi- Ac Standing Ac invading Ac from Cu Ac with Ac Ac of The number at the lower left is the a/o Ns transparent Lenticularis sky As / Ns congestus chaotic sky Next to the visibility is the present dew point temperature. -

Eye-Tracking Evaluation of Weather Web Maps

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Eye-tracking Evaluation of Weather Web Maps Stanislav Popelka , Alena Vondrakova * and Petra Hujnakova Department of Geoinformatics, Faculty of Science, Palacký University Olomouc, 17. listopadu 50, 77146 Olomouc, Czech Republic; [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (P.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420585634517 Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 28 May 2019; Published: 30 May 2019 Abstract: Weather is one of the things that interest almost everyone. Weather maps are therefore widely used and many users use them in everyday life. To identify the potential usability problems of weather web maps, the presented research was conducted. Five weather maps were selected for an eye-tracking experiment based on the results of an online questionnaire: DarkSky, In-Poˇcasí, Windy, YR.no, and Wundermap. The experiment was conducted with 34 respondents and consisted of introductory, dynamic, and static sections. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of recorded data was performed together with a think-aloud protocol. The main part of the paper describes the results of the eye-tracking experiment and the implemented research, which identify the strengths and weaknesses of the evaluated weather web maps and point out the differences between strategies in using maps by the respondents. The results include findings such as the following: users worked with web maps in the simplest form and they did not look for hidden functions in the menu or attempt to find any advanced functionality; if expandable control panels were available, the respondents only looked at them after they had examined other elements; map interactivity was not an obstacle unless it contained too much information or options to choose from; searching was quicker in static menus that respondents did not have to switch on or off; the graphic design significantly influenced respondents and their work with the web maps. -

Weather Forecasting Activities.Pdf

Weather Forecasting Weather Map and Forecasting Practice Incorporating a Fusion of Knowledge Involving Air Masses, Fronts, and Air Pressure Content Weather Forecasting Below, match the map with the appropriate profession: Weather Map Meteorologist Use the symbols below as a reference: Cold Front Warm Front High Pressure Low Pressure Clouds Rain Thunderstorms Hurricane Weather Conditions City Sunny, high temperature of 82°F Thunderstorms, high temperature of 91°F Sunny, high temperature of 75°F Rain, high temperature of 80°F Partly cloudy, high temperature of 73°F Mostly cloudy, high temperature of 92°F Scenario Answer Showers and thunderstorms; HOT and humid Hurricane just off the coast Center of low pressure Cold front Cool with highs in the low 70’s Sunny and VERY HOT!!! Color Precipitation Type Image SNOW RAIN ICE Detroit, Michigan Boston, Massachusetts Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Raleigh, North Carolina Phoenix, Arizona Orlando, Florida Weather Conditions City Moderate/Heavy Snow Warm and Dry Showers and Thunderstorms Ice Cold and Dry Minneapolis Houston San Francisco New York City Seattle Atlanta Miami Texas Between Chicago and Wyoming New York City Southern California and Seattle Arizona Philadelphia Raleigh Orlando Boston/Detroit Phoenix 3 Day Weather Forecasting Weather Map and Forecasting Practice Incorporating a Fusion of Knowledge Involving Atmospheric Variables Philadelphia,, PA Madison, WI Pittsburgh,PA Chicago, IL Flagstaff, AZ Atlanta, GA Phoenix, AZ The above is a daily weatha er map for which date? a DECEMBER 24, 2013 MAY 14, 2014 On the weather map above the forecasted weather is: A VARIETY SIMILAR Weather Forecast for Wednesday May 14, 2014 City Weather Forecast Image Atlanta, GA Pittsburgh, PA Madison, WI Phoenix, AZ Flagstaff, AZ Use the following information to make a reasonable weather forecast for the next day: Thursday May 15, 2014 Over the course of the next 24 hours the low pressure system in Louisiana will track to the northeast along the cold front . -

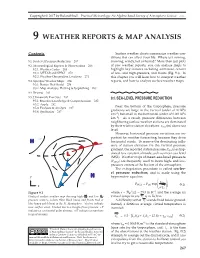

9 Weather Reports & Map Analysis

Copyright © 2017 by Roland Stull. Practical Meteorology: An Algebra-based Survey of Atmospheric Science. v1.02b 9 WEATHER REPORTS & MAP ANALYSIS Contents Surface weather charts summarize weather con- ditions that can affect your life. Where is it raining, 9.1. Sea-level Pressure Reduction 267 snowing, windy, hot or humid? More than just plots 9.2. Meteorological Reports & Observations 268 of raw weather reports, you can analyze maps to 9.2.1. Weather Codes 268 highlight key features including airmasses, centers 9.2.2. METAR and SPECI 270 of low- and high-pressure, and fronts (Fig. 9.1). In 9.2.3. Weather-Observation Locations 271 this chapter you will learn how to interpret weather 9.3. Synoptic Weather Maps 274 reports, and how to analyze surface weather maps. 9.3.1. Station Plot Model 274 9.3.2. Map Analysis, Plotting & Isoplething 280 9.4. Review 282 9.5. Homework Exercises 282 9.1. SEA-LEVEL PRESSURE REDUCTION 9.5.1. Broaden Knowledge & Comprehension 282 9.5.2. Apply 282 Near the bottom of the troposphere, pressure 9.5.3. Evaluate & Analyze 287 9.5.4. Synthesize 287 gradients are large in the vertical (order of 10 kPa km–1) but small in the horizontal (order of 0.001 kPa km–1). As a result, pressure differences between neighboring surface weather stations are dominated by their relative station elevations zstn (m) above sea level. However, horizontal pressure variations are im- cP portant for weather forecasting, because they drive H horizontal winds. To remove the dominating influ- ence of station elevation via the vertical pressure gradient, the reported station pressure Pstn is extrap- L olated to a constant altitude such as mean sea level (MSL). -

Weather Forecasting Webquest

Weather Forecasting Webquest Name ____________________________________________________________ Begin by going to the following website: http://www.oar.noaa.gov/k12/html/forecasting2.html Click on the Get info.1 link Weather Symbols Click on the symbols site…. Read the chart and fill in the symbols. Click "Back" to return to the Forecasting "Get Info.1" web page. Cloud Cover Symbols Click on the "Project Cloud Cover" site. 1. Describe how you would show that the sky was 50% cloudy. 2. Draw a sky that has about 10% cloud coverage Click back and then…… Storm Structure Click on the "Project Wind Speed Symbols" site 1. How do you show the direction the wind is blowing from? 2. What is the relationship between the length of the lines on the barb and the wind speed? 3. Draw a picture that would represent southernly wind blowing about 15 knots with clear skies. 4. Draw a model that would show a northwesterly wind blowing at 20 knots with 25% cloud cover. 5. Convert 20 knots to miles per hour (show how you got your answer). 6. Draw a station model (wind barb) showing 86 miles per hour southwesterly wind and completely overcast skies (first convert to knots from mph) Click back to return to “Get Info.1” then foreward at bottom of page Isobars Click on the Project Isobars site. 1. What are isobars? 2. Describe how the wind would move at a: Cyclone – Anti-cyclone – 3. Using what you just read about, how can we use isobars to show the direction that the wind is blowing? Click back and then to the “Get info.2” web page, then the Weather Systems page 1. -

Lecture 14. Extratropical Cyclones • in Mid-Latitudes, Much of Our Weather

Lecture 14. Extratropical Cyclones • In mid-latitudes, much of our weather is associated with a particular kind of storm, the extratropical cyclone Cyclone: circulation around low pressure center Some midwesterners call tornadoes cyclones Tropical cyclone = hurricane • Extratropical cyclones derive their energy from horizontal temperature con- trasts. • They typically form on a boundary between a warm and a cold air mass associated with an upper tropospheric jet stream • Their circulations affect the entire troposphere over a region 1000 km or more across. • Extratropical cyclones tend to develop with a particular lifecycle . • The low pressure center moves roughly with the speed of the 500 mb wind above it. • An extratropical cyclone tends to focus the temperature contrasts into ‘fron- tal zones’ of particularly rapid horizontal temperature change. The Norwegian Cyclone Model In 1922, well before routine upper air observations began, Bjerknes and Sol- berg in Bergen, Norway, codified experience from analyzing surface weather maps over Europe into the Norwegian Cyclone Model, a conceptual picture of the evolution of an ET cyclone and associated frontal zones at ground They noted that the strongest temperature gradients usually occur at the warm edge of the frontal zone, which they called the front. They classified fronts into four types, each with its own symbol: Cold front - Cold air advancing into warm air Warm front - Warm air advancing into cold air Stationary front - Neither airmass advances Occluded front - Looks like a cold front -

The Daily Weather Map: a Cartographic History of Meteorology

The Daily Weather Map: A Cartographic History of Meteorology Stephen Vermette, SUNY Buffalo State, Department of Geography & Planning U.S. Daily Weather Map remains a sheet of paper but additional maps added: High and Low Temperatures; Precipitation Areas and Amounts; The U.S. Daily Weather Map has been continuously 1:30 p.m. Weather Map; and 700 mb Chart. published for over 140 years. Prior to the Daily Weather Map, James Pollard Espy (1785–1860) produced one of the first U.S. weather maps, noting that “A well-arranged system of observations spread over the course of the country, would accomplish more in one year, than observations at a few isolated posts, however accurate and complete, to the end of First available on Internet for time”. An examination of these early maps, and viewing and downloading. specifically the Daily Weather Map, reveals the evolution of meteorological science in this country. The relevance of the maps evolved – initially they were outdated before distribution, evolved to serve as a timely source of information, and later were relegated Precipitation areas Last 24 as an archival record. The early maps were confined hours) are shaded. Low by a limited number of observing stations, later pressure storm tracks are Reduced in size isotherms and isobars could be drawn as the shown. Along with isotherms, and expanded dashed red isolines indicate observing network became denser and expanded to cover a one changes in temperature over week period. westward. The maps reveal the early struggle with the the past 24 hours. Tabular visualization of weather data which eventually led to station data expanded, river gauge stations added, and the development of the ‘station model’. -

Weather Forecasting

Weather Forecasting GEOL 1350: Introduction To Meteorology 1 Overview • Weather Forecasting Tools • Weather Forecasting Methods • Weather Forecasting Using Surface Charts 2 Weather Forecasting Tools To help forecasters handle all the available charts and maps, high-speed data modeling systems using computers are employed by the National Weather Service. Advanced Weather Interactive Processing System (AWIPS) has data communications, storage, processing, and display capabilities to better help the individual forecaster extract and assimilate information from available data. 3 Weather Forecasting Tools AWIPS computer work station provides various weather maps and overlays on different screens. AWIPS gathers data from Doppler radar system, satellite imagery, and the automated surface observing system that are operational at selected airports and other sites through out the United States. 4 Weather Forecasting Tools • Doppler radar detects severe weather size, movement, and intensity A forecaster can project the movement of the storm and warn those areas in the path of severe weather. Doppler radar data from Melbourne, Florida, on Mar 25, 1992, during the time of a severe hailstorm. The hail algorithm determined that there was 100% probability that the storm was producing hail. It also estimated that maximum size of the 5 hailstones to be greater than 3 inches. Weather Forecasting Tools • It is essential that the data can be easily accessible for the forecasters and in a format that allows several weather variables to be viewed at one time. • Meteogram is a chart that shows how one or more weather variables has changed at a station over a given period of time. Meteogram illustrates predicted weather • Meteogram may represent how elements at Buffalo from 1 pm Jan 18 to 7 pm air temperature, dew point, and Jan 20. -

National Weather Service Glossary Page 1 of 254 03/15/08 05:23:27 PM National Weather Service Glossary

National Weather Service Glossary Page 1 of 254 03/15/08 05:23:27 PM National Weather Service Glossary Source:http://www.weather.gov/glossary/ Table of Contents National Weather Service Glossary............................................................................................................2 #.............................................................................................................................................................2 A............................................................................................................................................................3 B..........................................................................................................................................................19 C..........................................................................................................................................................31 D..........................................................................................................................................................51 E...........................................................................................................................................................63 F...........................................................................................................................................................72 G..........................................................................................................................................................86 -

Weather Patterns

NAME: DATE: CLASS Pd; Forecasting Weather MAP Worksheet #1 Figures 1—4 are weather maps for a 24-hour period. The maps show the position of pressure systems and fronts in the United States every 12 hours, beginning at 12:00 A.M. on Thursday. Examine the maps and think about what is occurring. Then answer the following questions. 1. Briefly describe the movement of the high and low pressure systems shown on the maps. 2. Why do you think the cold front in Figure 1 developed? 3. What conditions were necessary for the development of the warm front in Figure 3? 4. What may be happening to the cold air mass as it moves southward from the Great Plains? 5. Explain what is happening to air along the cold front. NAME: DATE: CLASS Pd; Forecasting Weather MAP Worksheet #2 1. This weather map shows conditions during the __________ season of the year. 2. What are the probable weather conditions in each of these states? a. Michigan d. South Carolina b. New York e. Montana c. Minnesota f. Texas 3. What kind of weather can Wyoming soon expect? 4. What is the approximate temperature of each of these cities? a. ______ New Orleans, LA d. ______ San Diego, CA b. ______ El Paso, TX e. ______ Miami, FL c. ______ Denver, CO f. ______ Memphis, TN NAME: DATE: CLASS Pd; Forecasting Weather MAP Worksheet #3 NAME: DATE: CLASS Pd: Forecasting Weather MAP Worksheet #3 Observe the movement of highs and lows and fronts on the weather maps for Saturday, Sunday and Monday on the maps shown above.