Surface Air Pressure Patterns and Winds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Maths

Summer Term Curriculum Overview for Year 5 2021 only Black-First half (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) Red- Second half (The Secret Garden) English Reading Comprehension Planning, Composing and Evaluating Maths Develop ideas through reading and research Grammar, Punctuation and Vocabulary Use a wide knowledge of text types, forms and styles to inform Check that the text makes sense to them and Fractions B (calculating) (4 weeks) Decimals and percentages (3 weeks) Decimals (5 weeks) their writing Use correct grammatical terminology when discuss their understanding discussing their writing Plan and write for a clear purpose and audience Use imagination and empathy to explore a text Ensure that the content and style of writing accurately reflects Decimals (5 weeks) Geometry: angles (just shape work, angles have been covered) Geometry: position and Use the suffixes –ate, -ise, and –ify to convert nouns beyond the page the purpose or adjectives into verbs Answer questions drawing on information from Borrow and adapt writers’ techniques from book, screen and direction Measurement: volume and converting units Understand what parenthesis is several places in the text stage Recognise and identify brackets and dashes Predict what may happen using stated and Balance narrative writing between action, description and dialogue Use brackets, dashes or commas for parenthesis implied details and a wider personal Geography Evaluate the work of others and suggest improvements Ensure correct subject verb agreement understanding of the world Evaluate their work effectively and make improvements based Name, locate and describe major world cities. Revisit: Identify the location and explain the Summarise using an appropriate amount of detail on this function of the Prime (or Greenwich) Meridian and different time zones (including day and History as evidence Proof–read for spelling and punctuation errors night). -

Years 3–4, and the Others in Years 5–6

Unit 16 What’s in the news? ABOUT THE UNIT This is a ‘continuous’ unit, designed to be developed at various points through the key stage. It shows how news items at a widening range of scales can be used to develop geographical skills and ideas. The unit can be used flexibly when relevant news events occur. The teaching ideas could be selected and used outside designated geography curriculum time, eg during assembly, a short activity at the beginning or end of the day, or within a context for literacy and mathematics work. Alternatively the ideas could be integrated within other geography units where appropriate, eg weather reports could be linked to work on weather and distant localities, see Unit 7. The first three sections are designed to be used in years 3–4, and the others in years 5–6. The unit offers links to literacy, mathematics, speaking and listening and IT. Widening range of scales Undertake fieldwork Wider context Use globes, maps School locality and atlases UK locality Use secondary sources Overseas locality Identify places on Physical and human features maps A, B and C Similarities and differences Use ICT Changes Weather: seasons, world weather Environment: impact Other aspects of skills, places and themes may be covered depending on the content of the news item. VOCABULARY RESOURCES In this unit, children are likely to use: • newspapers • news, current affairs, issues, weather, weather symbols, climate, country, • access to the internet continent, land use, environmental quality, community, physical features, human • local -

Chapter 7.0 – Determining Wind Direction Section 7.1 Overview Of

Chapter 7.0 – Determining Wind Direction Section 7.1 Overview of Wind Direction The wind direction is a measure or indication of where the air movement originated from. The wind direction can be measured through the use of a wind sock, wind vane, or a light object attached to a pole and string (example: A ping pong ball attached to a string which is tied to a stick). Wind direction is generally reported in either Azimuth degrees or Cardinal direction. Azimuth uses a circle with the northern most position indicating 0 degrees. The Cardinal direction system gives an Azimuth degree value a name. For example, 180 degrees is South(S) and 270 degrees is West (W) (See Figure 18 - A basic compass rose). Figure 18 - A basic compass rose Section 7.2 Overview of the homemade Wind Vane The wind vane used in this design was a homemade wind vane using a miniature absolute magnetic shaft encoder. The encoder chosen for use was the MA3 produced by US Digital. The purpose for choosing this specific encoder in regards to this design was that the MA3 met four (4) critical objectives. First, the MA3 was the correct size for the application. Second, the MA3 uses an analog output of 0 volts to 5 volts with respect to the current positions (See Figure 19 – MA3 Output behaviour) Figure 19 – MA3 Output behaviour Third, the MA3 uses a 5 volt input. This was a major consideration when choosing an encoder as a 5 volt input allowed for a more simple integration. Fourth, and final, the MA3 met the requirements of being able to function in an adverse environment, having an operational temperature of -40 ºC to +125 ºC. -

Weather Maps

Name: ______________________________________ Date: ________________________ Student Exploration: Weather Maps Vocabulary: air mass, air pressure, cold front, high-pressure system, knot, low-pressure system, precipitation, warm front Prior Knowledge Questions (Do these BEFORE using the Gizmo.) 1. How would you describe your weather today? ____________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ 2. What information is important to include when you are describing the weather? __________ _________________________________________________________________________ Gizmo Warm-up Data on weather conditions is gathered from weather stations all over the world. This information is combined with satellite and radar images to create weather maps that show current conditions. With the Weather Maps Gizmo, you will use this information to interpret a variety of common weather patterns. A weather station symbol, shown at right, summarizes the weather conditions at a location. 1. The amount of cloud cover is shown by filling in the circle. A black circle indicates completely overcast conditions, while a white circle indicates a clear sky. What percentage of cloud cover is indicated on the symbol above? ____________________ 2. Look at the “tail” that is sticking out from the circle. The tail points to where the wind is coming from. If the tail points north, a north wind is moving from north to south. What direction is the wind coming from on the symbol above? ________________________ 3. The “feathers” that stick out from the tail indicate the wind speed in knots. (1 knot = 1.151 miles per hour.) A short feather represents 5 knots (5.75 mph), a long feather represents 10 knots (11.51 mph), and a triangular feather stands for 50 knots (57.54 mph). -

NWS Unified Surface Analysis Manual

Unified Surface Analysis Manual Weather Prediction Center Ocean Prediction Center National Hurricane Center Honolulu Forecast Office November 21, 2013 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers…………….3 Chapter 2: Datasets available for creation of the Unified Analysis………...…..5 Chapter 3: The Unified Surface Analysis and related features.……….……….19 Chapter 4: Creation/Merging of the Unified Surface Analysis………….……..24 Chapter 5: Bibliography………………………………………………….…….30 Appendix A: Unified Graphics Legend showing Ocean Center symbols.….…33 2 Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers 1. INTRODUCTION Since 1942, surface analyses produced by several different offices within the U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Weather Service (NWS) were generally based on the Norwegian Cyclone Model (Bjerknes 1919) over land, and in recent decades, the Shapiro-Keyser Model over the mid-latitudes of the ocean. The graphic below shows a typical evolution according to both models of cyclone development. Conceptual models of cyclone evolution showing lower-tropospheric (e.g., 850-hPa) geopotential height and fronts (top), and lower-tropospheric potential temperature (bottom). (a) Norwegian cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) and (III) narrowing warm sector, (IV) occlusion; (b) Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) frontal fracture, (III) frontal T-bone and bent-back front, (IV) frontal T-bone and warm seclusion. Panel (b) is adapted from Shapiro and Keyser (1990) , their FIG. 10.27 ) to enhance the zonal elongation of the cyclone and fronts and to reflect the continued existence of the frontal T-bone in stage IV. -

Impact of Cloud Analysis on Numerical Weather Prediction in the Galician Region of Spain

Impact of Cloud Analysis on Numerical Weather Prediction in the Galician Region of Spain M. J. SOUTO, C. F. BALSEIRO AND V. P…REZ-MU—UZURI Group of Nonlinear Physics, Faculty of Physics, University of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain Ming Xue University of Oklahoma, School of Meteorology, and CAPS Oklahoma, USA Keith BREWSTER Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms, Oklahoma, USA April, 2001 Revised December, 2001 Corresponding author address: Dra. M. J. Souto, Group of Nonlinear Physics Faculty of Physics, University of Santiago de Compostela E-15706, Santiago de Compostela, Spain e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Advanced Regional Prediction System (ARPS) is applied to operational numerical weather forecast in Galicia, northwest Spain. A 72-hour forecast at a 10-km horizontal resolution is produced dta for the region. Located on the northwest coast of Spain and influenced by the Atlantic weather systems, Galicia has a high percentage (almost 50%) of rainy days per year. For these reasons, the precipitation processes and the initialization of moisture and cloud fields are very important. Even though the ARPS model has a sophisticated data analysis system (ADAS) that includes a 3D cloud analysis package, due to operational constraint, our current forecast starts from 12-hour forecast of the NCEP AVN model. Still, procedures from the ADAS cloud analysis are being used to construct the cloud fields based on AVN data, and then applied to initialize the microphysical variables in ARPS. Comparisons of the ARPS predictions with local observations show that ARPS can predict quite well both the daily total precipitation and its spatial distribution. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Chapter 4: Pressure and Wind

ChapterChapter 4:4: PressurePressure andand WindWind Pressure, Measurement, Distribution Hydrostatic Balance Pressure Gradient and Coriolis Force Geostrophic Balance Upper and Near-Surface Winds ESS5 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu OneOne AtmosphericAtmospheric PressurePressure The average air pressure at sea level is equivalent to the pressure produced by a column of water about 10 meters (or about 76 cm of mercury column). This standard atmosphere pressure is often expressed as 1013 mb (millibars), which means a pressure of about 1 kilogram per square centimeter (from The Blue Planet) 2 (14.7lbs/in ). ESS5 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu UnitsUnits ofof AtmosphericAtmospheric PressurePressure Pascal (Pa): a SI (Systeme Internationale) unit for air pressure. 1 Pa = force of 1 newton acting on a surface of one square meter 1 hectopascal (hPa) = 1 millibar (mb) [hecto = one hundred =100] Bar: a more popular unit for air pressure. 1 bar = 1000 hPa = 1000 mb One atmospheric pressure = standard value of atmospheric pressure at lea level = 1013.25 mb = 1013.25 hPa. ESS5 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu MeasurementMeasurement ofof AtmosAtmos.. PressurePressure Mercury Barometers – Height of mercury indicates downward force of air pressure – Three barometric corrections must be made to ensure homogeneity of pressure readings – First corrects for elevation, the second for air temperature (affects density of mercury), and the third involves a slight correction for gravity with latitude Aneroid Barometers – Use a collapsible chamber which compresses proportionally to air pressure – Requires only an initial adjustment for ESS5 elevation Prof. Jin-Yi Yu PressurePressure CorrectionCorrection forfor ElevationElevation Pressure decreases with height. Recording actual pressures may be misleading as a result. -

Anticyclones

Anticyclones Background Information for Teachers “High and Dry” A high pressure system, also known as an anticyclone, occurs when the weather is dominated by stable conditions. Under an anticyclone air is descending, maybe linked to the large scale pattern of ascent and descent associated with the Global Atmospheric Circulation, or because of a more localized pattern of ascent and descent. As shown in the diagram below, when air is sinking, more air is drawn in at the top of the troposphere to take its place and the sinking air diverges at the surface. The diverging air is slowed down by friction, but the air converging at the top isn’t – so the total amount of air in the area increases and the pressure rises. More for Teachers – Anticyclones Sinking air gets warmer as it sinks, the rate of evaporation increases and cloud formation is inhibited, so the weather is usually clear with only small amounts of cloud cover. In winter the clear, settled conditions and light winds associated with anticyclones can lead to frost. The clear skies allow heat to be lost from the surface of the Earth by radiation, allowing temperatures to fall steadily overnight, leading to air or ground frosts. In 2013, persistent High pressure led to cold temperatures which caused particular problems for hill sheep farmers, with sheep lambing into snow. In summer the clear settled conditions associated with anticyclones can bring long sunny days and warm temperatures. The weather is normally dry, although occasionally, localized patches of very hot ground temperatures can trigger thunderstorms. An anticyclone situated over the UK or near continent usually brings warm, fine weather. -

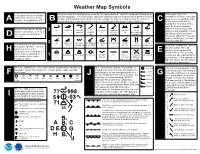

Print Key. (Pdf)

Weather Map Symbols Along the center, the cloud types are indicated. The top symbol is the high-level cloud type followed by the At the upper right is the In the upper left, the temperature mid-level cloud type. The lowest symbol represents low-level cloud over a number which tells the height of atmospheric pressure reduced to is plotted in Fahrenheit. In this the base of that cloud (in hundreds of feet) In this example, the high level cloud is Cirrus, the mid-level mean sea level in millibars (mb) A example, the temperature is 77°F. B C C to the nearest tenth with the cloud is Altocumulus and the low-level clouds is a cumulonimbus with a base height of 2000 feet. leading 9 or 10 omitted. In this case the pressure would be 999.8 mb. If the pressure was On the second row, the far-left Ci Dense Ci Ci 3 Dense Ci Cs below Cs above Overcast Cs not Cc plotted as 024 it would be 1002.4 number is the visibility in miles. In from Cb invading 45° 45°; not Cs ovcercast; not this example, the visibility is sky overcast increasing mb. When trying to determine D whether to add a 9 or 10 use the five miles. number that will give you a value closest to 1000 mb. 2 As Dense As Ac; semi- Ac Standing Ac invading Ac from Cu Ac with Ac Ac of The number at the lower left is the a/o Ns transparent Lenticularis sky As / Ns congestus chaotic sky Next to the visibility is the present dew point temperature. -

Eye-Tracking Evaluation of Weather Web Maps

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Eye-tracking Evaluation of Weather Web Maps Stanislav Popelka , Alena Vondrakova * and Petra Hujnakova Department of Geoinformatics, Faculty of Science, Palacký University Olomouc, 17. listopadu 50, 77146 Olomouc, Czech Republic; [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (P.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420585634517 Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 28 May 2019; Published: 30 May 2019 Abstract: Weather is one of the things that interest almost everyone. Weather maps are therefore widely used and many users use them in everyday life. To identify the potential usability problems of weather web maps, the presented research was conducted. Five weather maps were selected for an eye-tracking experiment based on the results of an online questionnaire: DarkSky, In-Poˇcasí, Windy, YR.no, and Wundermap. The experiment was conducted with 34 respondents and consisted of introductory, dynamic, and static sections. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of recorded data was performed together with a think-aloud protocol. The main part of the paper describes the results of the eye-tracking experiment and the implemented research, which identify the strengths and weaknesses of the evaluated weather web maps and point out the differences between strategies in using maps by the respondents. The results include findings such as the following: users worked with web maps in the simplest form and they did not look for hidden functions in the menu or attempt to find any advanced functionality; if expandable control panels were available, the respondents only looked at them after they had examined other elements; map interactivity was not an obstacle unless it contained too much information or options to choose from; searching was quicker in static menus that respondents did not have to switch on or off; the graphic design significantly influenced respondents and their work with the web maps. -

Anticyclones – High Pressure Task 11 A: Read the Notes on High Pressure

Anticyclones – High pressure Task 11 A: Read the notes on high pressure. B: Watch the video clip on Anticyclones and sing along! C: Write out the information and fill in the blanks. D: Print/ sketch the diagram and add the labels. E: Using the information on summer and winter anticyclones, fill in the table to identify how they are similar and different in summer and winter F: Write a paragraph describing the hazards for people that are created by summer and winter anticyclones. G: Watch the two video clips on the 2003 European heatwave and write down 10 facts you have learned. H: Quiz, is it an anticyclone or a depression? I: Complete the grid comparing anticyclones and depressions. A WHAT CAUSES HIGH PRESSURE? • When air high in the atmosphere is cold, it falls towards the earth’s surface. • Falling air increases the weight of air pressing down on the Earth’s surface. • This means that air pressure is high • Because the air is falling, not rising there is no clouds forming • A high pressure system is called an ANTICYCLONE. B https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCz8J_mxswg C Anticyclones • Anticyclones are areas of high pressure in the atmosphere, where the air is sinking. • High pressure brings settled weather with clear,, bright skies. • As the air is sinking, not rising, no clouds or rain can form. • Winds may be very light . • In summer anticyclones bring dry, hot weather. • High pressure systems are slow moving and can persist over an area for a long period of time, such as days or weeks.