Gazette Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

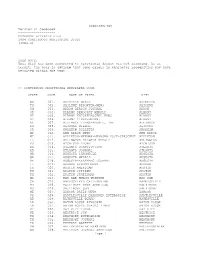

Appendix File 1984 Continuous Monitoring Study (1984.S)

appcontm.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1984 CONTINUOUS MONITORING STUDY (1984.S) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> CONTINUOUS MONITORING NEWSPAPER CODE STATE CODE NAME OF PAPER CITY WA 001. ABERDEEN WORLD ABERDEEN TX 002. ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS ABILENE OH 003. AKRON BEACON JOURNAL AKRON OR 004. ALBANY DEMOCRAT-HERALD ALBANY NY 005. ALBANY KNICKERBOCKER NEWS ALBANY NY 006. ALBANY TIMES-UNION, ALBANY NE 007. ALLIANCE TIMES-HERALD, THE ALLIANCE PA 008. ALTOONA MIRROR ALTOONA CA 009. ANAHEIM BULLETIN ANAHEIM MI 010. ANN ARBOR NEWS ANN ARBOR WI 011. APPLETON-NEENAH-MENASHA POST-CRESCENT APPLETON IL 012. ARLINGTON HEIGHTS HERALD ARLINGTON KS 013. ATCHISON GLOBE ATCHISON GA 014. ATLANTA CONSTITUTION ATLANTA GA 015. ATLANTA JOURNAL ATLANTA GA 016. AUGUSTA CHRONICLE AUGUSTA GA 017. AUGUSTA HERALD AUGUSTA ME 018. AUGUSTA-KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA IL 019. AURORA BEACON NEWS AURORA TX 020. AUSTIN AMERICAN AUSTIN TX 021. AUSTIN CITIZEN AUSTIN TX 022. AUSTIN STATESMAN AUSTIN MI 023. BAD AXE HURON TRIBUNE BAD AXE CA 024. BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIAN BAKERSFIELD MD 025. BALTIMORE NEWS AMERICAN BALTIMORE MD 026. BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE ME 027. BANGOR DAILY NEWS BANGOR OK 028. BARTLESVILLE EXAMINER-ENTERPRISE BARTLESVILLE AR 029. BATESVILLE GUARD BATESVILLE LA 030. BATON ROUGE ADVOCATE BATON ROUGE LA 031. BATON ROUGE STATES TIMES BATON ROUGE MI 032. BAY CITY TIMES BAY CITY NE 033. BEATRICE SUN BEATRICE TX 034. BEAUMONT ENTERPRISE BEAUMONT TX 035. BEAUMONT JOURNAL BEAUMONT PA 036. -

George Chaplin: W. Sprague Holden: Newbold Noyes: Howard 1(. Smith

Ieman• orts June 1971 George Chaplin: Jefferson and The Press W. Sprague Holden: The Big Ones of Australian Journalism Newbold Noyes: Ethics-What ASNE Is All About Howard 1(. Smith: The Challenge of Reporting a Changing World NEW CLASS OF NIEMAN FELLOWS APPOINTED NiemanReports VOL. XXV, No. 2 Louis M. Lyons, Editor Emeritus June 1971 -Dwight E. Sargent, Editor- -Tenney K. Lehman, Executive Editor- Editorial Board of the Society of Nieman Fellows Jack Bass Sylvan Meyer Roy M. Fisher Ray Jenkins The Charlotte Observer Miami News University of Missouri Alabama Journal George E. Amick, Jr. Robert Lasch Robert B. Frazier John Strohmeyer Trenton Times St. Louis Post-Dispatch Eugene Register-Guard Bethlehem Globe-Times William J. Woestendiek Robert Giles John J. Zakarian E. J. Paxton, Jr. Colorado Springs Sun Knight Newspapers Boston Herald Traveler Paducah Sun-Democrat Eduardo D. Lachica Smith Hempstone, Jr. Rebecca Gross Harry T. Montgomery The Philippines Herald Washington Star Lock Haven Express Associated Press James N. Standard George Chaplin Alan Barth David Kraslow The Daily Oklahoman Honolulu Advertiser Washington Post Los Angeles Times Published quarterly by the Society of Nieman Fellows from 48 Trowbridge Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138. Subscription $5 a year. Third class postage paid at Boston, Mass. "Liberty will have died a little" By Archibald Cox "Liberty will have died a little," said Harvard Law allowed to speak at Harvard-Fidel Castro, the late Mal School Prof. Archibald Cox, in pleading from the stage colm X, George Wallace, William Kunstler, and others. of Sanders Theater, Mar. 26, that radical students and Last year, in this very building, speeches were made for ex-students of Harvard permit a teach-in sponsored by physical obstruction of University activities. -

United States Newspapers Index (PDF)

U.S. Newspapers Briscoe Center for American History The Briscoe Center for American History's newspaper collections also contain titles from around the United States. These titles are limited to the few dates listed or an incomplete, brief date run. A significant part of this collection consists of several hundred linear feet of newspapers published in every state of the Confederacy from the 1790s through the early 1900s. Holdings include extensive runs of early newspapers in hard copy from Charleston, South Carolina (1795-1942), Augusta, Georgia (1806-1885), New Orleans, Louisiana (1837-1914), and Little Rock, Arkansas (1819-1863). Many issues are scarce or extremely rare, including the only known copies of several important antebellum Louisiana and Mississippi newspapers. Many of these newspapers are in Original Format (OR), and cannot be photocopied. Patrons have the option of photographing these newspapers themselves with no additional lighting and under the direct supervision of the Reading Room staff. Patrons must complete an Items Photographed by Patrons form. The resulting images are for research only and may not be published. Frequency: d=daily, w=weekly, tw=tri-weekly, sw=semi-weekly, m=monthly, sm=semi-monthly, u=unknown Format: OR=Original newspaper, MF=Microfilm, RP=Reproduction *an asterisk indicates all or part of the newspaper is stored offsite and requires advance notice for retrieval ALABAMA Alabama, Birmingham Sunday Morning Chronicle (w) Dec 9, 1883 OR (oversize) Alabama, Carrollton West Alabamian (w) Jan 1870-Dec -

Arkansas Democrat Memories

The David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History University of Arkansas 365 N. McIlroy Ave. Fayetteville, AR 72701 (479) 575-6829 This oral history interview is based on the memories and opinions of the subject being interviewed. As such, it is subject to the innate fallibility of memory and is susceptible to inaccuracy. All researchers using this interview should be aware of this reality and are encouraged to seek corroborating documentation when using any oral history interview. Arkansas Democrat Memories By Jerry McConnell Greenwood, Arkansas 11 September 2008 Working for the Arkansas Democrat in the middle of the twentieth century was a test of anyone’s dedication to journalism. Poor wages, six-day weeks, lack of fringe benefits, lack of air conditioning and other amenities made it eventually a frustrating experience. I wouldn’t have missed it for anything. It was a good place to learn, there were some great people with whom to share your suffering, and we had some fun. We sometimes did a good job of reporting the news, some of which might not have been reported without us. I went to work for the Arkansas Democrat in June 1951, two days after graduating from the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville with a Bachelor of Science degree in journalism. My starting salary was $45.12 a week for a six-day week. I did not figure out until years later that I was making less than a dollar an hour and was probably making just a few cents an hour over the federal minimum wage of 75 cents an hour. -

Gazette Project Interview with James O. Powell, Little Rock

Gazette Project Interview with James O. Powell, Little Rock, Arkansas, 3 February 2000 Interviewer: Ernie Dumas Ernie Dumas: This is February 3rd. James Powell: Right. ED: And I’m Ernie Dumas. And we’re talking to James O. Powell, Jim Powell, who was the editor of the editorial page of the Arkansas Gazette, from 1960 until 198 . JP: Well, actually, it was 1985. ED: 1985. And subsequent senior editor and columnist for the Arkansas Gazette. JP: Couple of years . ED: Jim, first I have to explain to you briefly that this is for the Arkansas Center for Oral and Visual History. And we need your permission to tape this interview with the understanding that your remarks can be used for research and whatever other purposes. It becomes a kind of a public document. JP: Okay. ED: You consent to that. JP: All right. ED: All right. Let’s start with your war record, I guess. You were born in Andalusia, Alabama. 1 JP: Right. ED: And, went to University of Florida. JP: I went to the public schools in Andalusia. And went to and graduated from the University of Florida, although there were two lapses. My sophomore year I transferred to the University of Alabama for one year, then returned to Florida for my junior year. Then, before my senior year, I laid out and worked for a year, first on the Alabama Journal in Montgomery and then on the old Columbus, Georgia, Free Press. I returned to Florida for my senior year and graduated with a B.A. J., one jump ahead of the draft board. -

Newspaper Guide CUSICK EDITS 2017

The Newberry Library Newspaper Collection U.S. Newspapers Date Year Newspaper Call # (if not full year) Alabama - Blakely 1818 12 Dec - 29 Dec Blakely Sun, and Alabama Advertiser Microfilm 850 1819 8 Jan - 2 Jun Blakely Sun, and Alabama Advertiser Microfilm 850 Alabama - Cahawba Cahawba Press and Alabama 10 Jul - Dec Microfilm 1115, No. 3 1819 Intelligencer 1820 8 Aug - 15 Dec Alabama Watchman Microfilm 1115, No. 4 Cahawba Press and Alabama Microfilm 1115, No. 3 1820 Intelligencer Alabama - Clairborne 1819 19 Mar - 15 Oct Alabama Courier Microfilm 1115, No. 2 Alabama - Huntsville 1816 21 Dec Huntsville Gazette Microfilm 1115, No. 1 Alabama - Mobile 1863 21 Jul Mobile Evening Telegraph Case FA6 .007 Alabama - Selma 1859 26 Jul Daily Selma Reporter Case fA6. 007 1859 26 Jul - 27 Jul Daily State Sentinel Case fA6. 007 1862 17 Jun Daily Selma Reporter Case fA6. 007 1862 16 Aug; 30 Dec Daily Selma Reporter Case fA6. 007 Notes: Also see Historical Newspaper Collection at ancestry.com Compiled by JECahill Scattered issues may be missing Feb 2005 U.S. Newspapers Date Year Newspaper Call # (if not full year) 1863 28 Jun Chattanooga Daily Rebel Case F834.004 1864 9 Mar; 19 Mar Daily Selma Reporter Case fA6. 007 1864 25 May Selma Morning Dispatch Case fA6. 007 1865 19 Apr Chattanooga Daily Rebel Case FA6 .007 1865 7 Jun; 22 Jun Federal Union Case fA6. 007 1865 12 Mar Selma Morning Dispatch Case fA6. 007 Alaska 1868 Mar - 15 Apr Alaska Herald Ayer f1 A32 1868 1967 1868 May Free Press and Alaska Herald Ayer f1 A32 1868 1967 1868 Jun - Dec Alaska Herald -

Nov/Dec 2019

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com November/December 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Raised from the dead: The Bigfork Eagle lives! u BY MARC WILSON SPECIAL TO NEWS & TECH Editor’s Note: The Bigfork, Montana, half that in the winter. The town Eagle resumed publication on Oct. 30. — some call it a village — sits on What’s the big deal with the rebirth of a small-town weekly newspaper? Our Marc the shores of Flathead Lake near Wilson tells you the back story. the confluence of the Swan and Flathead rivers. The snow-capped The most difficult — and re- Swan Mountains rise over the warding — job I ever had was edi- town to the west. Bigfork is used tor/publisher/janitor of the Bigfork by many as a gateway to Glacier Eagle, a small weekly newspaper National Park and the Bob Mar- in rural northwest Montana. shall Wilderness. Gourmet restau- My wife and I ran and co- rants serve a clientele that lives or owned the Eagle for 14 years be- camps on the edge of wilderness. fore selling it in 1997 so I could Visitors are reminded that grizzly devote fulltime to building Town- bears are first on the food chain in News, which we’d started in the Montana. No joke. back shop of the Eagle in 1989. It’s a beautiful place to live or Lee Enterprises bought the visit, but a very difficult place to Eagle from us before selling it to make a living or run a business, Hagadone Newspapers in the including a weekly newspaper. -

1960-1969 U.S. Newspapers

Chronological Indexes of United States Newspapers Available at the Library of Congress: 1960 - 1969 State City Title Audience MF # 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 AL Birmingham Birmingham news General 0934 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AL Mobile Mobile register General 0936 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AL Montgomery Montgomery advertiser General 0937 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AK Anchorage Anchorage daily news General 2414 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AK Anchorage Anchorage daily times General 0946 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - [Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec.] Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AK Cordova Cordova times General 0947 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AK Fairbanks Fairbanks news-miner General 0949 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AK Fairbanks Jessen's weekly (see Exception General 0948 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - none Report) Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Aug. 25 AK Fairbanks Tundra times General 0950 none none Oct. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. -

Southern Whites Respond to Brown V. Board of Education Gareth D

Volume 5 Article 6 2006 Voices of Moderation: Southern Whites Respond to Brown v. Board of Education Gareth D. Pahowka Gettysburg College Class of 2006 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Pahowka, Gareth D. (2006) "Voices of Moderation: Southern Whites Respond to Brown v. Board of Education," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 5 , Article 6. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol5/iss1/6 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Voices of Moderation: Southern Whites Respond to Brown v. Board of Education Abstract At the shining apex of racial reform in the civil rights era stands the historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision. Recently passing its fiftieth anniversary, the ruling struck down legal school segregation which had been upheld by the same court some fifty-eight years earlier in the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. Brown is highly revered today as a sacred document and cornerstone of American race-relations, but the ruling initially garnered widespread shock, outrage, and defiance in the bedrock of segregation, the deep South. At least that is what we have been told. A closer analysis of southern public opinion regarding Brown reveals a multitude of views ranging from pure racist condemnation to praised acceptance and affirmation of racial equality. -

Maidens of Miletos and Newspaper Coverage of Suicide: Examining Late Nineteenth and Late Twentieth Century Practice

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 270 826 CS 209 951 AUTHOR Olasky, Marvin N. TITLE Maidens of Miletos and Newspaper Coverage of Suicide: Examining Late Nineteenth and Late Twentieth Century Practice. PUB DATE Aug 86 NOTE 19p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (69th, Norman, OK, August 3-6, 1986). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Content Analysis; Death; Journalism; Media Research; *Newspapers; *News Reporting; *News Writing; *Press Opinion; Religion; *Social Change; Social History; Social Values; *Suicide; Value Judgment IDENTIFIERS Journalism History; Nineteenth Century; Twentieth Century ABSTRACT Recognizing that writing suicide stories iv hard for reporters, a study examined 1,010 suicide stories from the 1879-1900 era published in 12 newspapers from around the United States to determine how American journalists at other times carriedout similar assignments. The newspapers examined were the Atlanta "Constitution," Arkansas "Gazette," Chicago "Tribune," Dallas "Herald," Dallas "News," Los Angeles "Times," New York "Journal," New York "Times," New York "Tribune," San Antonio "Express," San Francisco "Examiner," and "Washington Post." The most surprising finding was th, explicitness of many suicide stories. All of thenewspapers surveyed, with the occasional exception of the Arkansas "Gazette,"gave prominent display to suicide stories, and included mention of base motive and/or bloody detail. The message provided by suicide stories was straightforward: suicide was wrong, socially and theologically. Today, greater concern for invasion of privacy andawareness of potential lawsuits sometimes keeps journalists from being explicit in their judgment of suicide's rightness or wrongness, regardless of their personal feelings. -

1980-1989 U.S. Newspapers

Chronological Indexes of United States Newspapers Available at the Library of Congress: 1980 - 1989 State City Title Audience MF # 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 AL Birmingham Birmingham news General 0934 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AL Mobile Mobile register General 0936 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AL Montgomery Montgomery advertiser General 0937 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AK Anchorage Anchorage daily news General 2414 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Jun. 15 / Jul. - Dec. AK Anchorage Anchorage daily times General 0946 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - none Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. July / Aug. 16 - Dec. AK Anchorage Tundra times General 3038 none none none Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. AK Cordova Cordova times General 0947 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. 7 none Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. - Jun. 23 AK Fairbanks Daily news-miner (see General 0949 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Exception Report) Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. Dec. 30 AK Juneau Juneau empire (see Exception General 0951 Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan. - Jan.