Concentration and Consolidation: How Chain Ownership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL NEWS IS a PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21St Century

LOCAL NEWS IS A PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21st Century INTRODUCTION A free and independent press was so fundamental to the founding vision of “Congress shall make no law democratic engagement and government accountability in the United States that it is called out in the First Amendment to the Constitution alongside individual respecting an establishment of freedoms of speech, religion, and assembly. Yet today, local newsrooms and religion, or prohibiting the free their ability to fulfill that lofty responsibility have never been more imperiled. At exercise thereof; or abridging the very moment when most Americans feel overwhelmed and polarized by a the freedom of speech, or of the barrage of national news, sensationalism, and social media, Colorado’s local news outlets – which are still overwhelmingly trusted and respected by local residents – press; or the right of the people are losing the battle for the public’s attention, time, and discretionary dollars.1 peaceably to assemble, and to What do Colorado communities lose when independent local newsrooms shutter, petition the Government for a cut staff, merge, or sell to national chains or investors? Why should concerned redress of grievances.” citizens and residents, as well as state and local officials, care about what’s happening in Colorado’s local journalism industry? What new models might First Amendment, U.S. Constitution transform and sustain the most vital functions of a free and independent Fourth Estate: to inform, equip, and engage communities in making democratic decisions? 1 81% of Denver-area adults say the local news media do very well to fairly well at keeping them informed of the important news stories of the day, 74% say local media report the news accurately, and 65% say local media cover stories thoroughly and provide news they use daily. -

Conference Attendees

CONFERENCE ATTENDEES Michelle Ackerman, CRM Product Manager, Brainworks, Sayville, NY Mark Adams, CEO, Adams Publishing Group, Coon Rapids, MN Mark Adams, Audience Acquisition/Retention Manager, The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC Mindy Aguon, CEO, The Guam Daily Post, Tamuning, GU Mickie Anderson, Local News Editor, The Gainesville Sun, Gainesville, FL Sara April, Vice President, Dirks, Van Essen, Murray & April, Santa Fe, NM Lloyd Armbrust, Chief Executive Officer, OwnLocal, Austin, TX Barry Arthur, Asst. Managing Editor Photo/Electronic Media, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock, AR Gordon Atkinson, Sr. Director, Marketing, Newspapers.com, Lehi, UT Donna Barrett, President/CEO, CNHI, Montgomery, AL Dana Bascom, Senior Sales Executive, Newzware ICANON, Hatfield, PA Mike Beatty, President, Florida, Adams Publishing Group, Venice, FL Ben Beaver, Account Representative, Second Street, St. Louis, MO Bob Behringer, President, Presteligence, North Canton, OH Julie Bergman, Vice President, Newspaper Group, Grimes, McGovern & Associates, East Grand Forks, MN Eddie Blakeley, COO, Journal Publishing, Tupelo, MS Gary Blakeley, CEO, PAGE Cooperative, King of Prussia, PA Deb Blanchard, Marketing, Our Hometown, Inc., Clifton Springs, NY Mike Blinder, Publisher, Editor & Publisher, Lutz, FL Robin Block-Taylor, EVP, Client Services, NTVB MEDIA, Troy, MI Cory Bollinger (Elizabeth), The Villages Media, Bloomington, IN Devlyn Brooks, President, Modulist, Fargo, ND Eileen Brown, Vice President/Director of Strategic Marketing and Innovation, Daily Herald, Arlington Heights, IL PJ Browning, President/Publisher, The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC Wright Bryan, Partner Manager, LaterPay, New York, NY John Bussian, Attorney, Bussian Law Firm, Raleigh, NC Scott Campbell, Publisher, The Columbian Publishing Company, Vancouver, WA Brent Carter, Senior Director, Newspapers.com, Lehi, UT Lloyd Case (Ellen), Fargo, ND Scott Champion, CEO, Champion Media, Mooresville, NC Jim Clarke, Director - West, The Associated Press, Denver, CO Matt Coen, President, Second Street, St. -

Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (75Th, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, August 5-8, 1992)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 349 622 CS 507 969 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (75th, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, August 5-8, 1992). Part XV: The Newspaper Business. INSTITUTION Seneca Nation Educational Foundation, Salamanca, N.Y. PUB DATE Aug 92 NOTE 324p.; For other sections of these proceedings, see CS 507 955-970. For 1991 Proceedings, see ED 340 045. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Business Administration; *Economic Factors; *Employer Employee Relationship; Foreign Countries; Journalism History; Marketing; *Mass Media Role; Media Research; *Newspapers; Ownership; *Publishing Industry; Trend Analysis IDENTIFIERS *Business Media Relationship; Indiana; Newspaper Circulation ABSTRACT The Newspaper Business section of the proceedings contains the following 13 papers: "Daily Newspaper Market Structure, Concentration and Competition" (Stephen Lacy and Lucinda Davenport); "Who's Making the News? Changing Demographics of Newspaper Newsrooms" (Ted Pease); "Race, Gender and White Male Backlash in Newspaper Newsrooms" (Ted Pease); "Race and the Politics of Promotion in Newspaper Newsrooms" (Ted Pease); "Future of Daily Newspapers: A Q-Study of Indiana Newspeople and Subscribers" (Mark Popovich and Deborah Reed); "The Relationship between Daily and Weekly Newspaper Penetration in Non-Metropolitan Areas" (Stephen Lacy and Shikha Dalmia); "Employee Ownership at Milwaukee and Cincinnati: A Study in Success and -

UA68/13/5 the Fourth Estate, Vol. 8, No. 1

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Student Organizations WKU Archives Records Fall 1983 UA68/13/5 The ourF th Estate, Vol. 8, No. 1 Sigma Delta Chi Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_org Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Public Relations and Advertising Commons Recommended Citation Sigma Delta Chi, "UA68/13/5 The ourF th Estate, Vol. 8, No. 1" (1983). Student Organizations. Paper 141. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_org/141 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Organizations by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The ~~ARCH1Vj.~ Fou rth Estaf1!'-' - k .- Vol. a No.1 FJII,1983 l'ubllaIMd by the Western Kentu,ky Unlyer~ty chapter of The Society of Profenionlol J ou rnlollJu, Slim", Deltl Chi 80,..lInl Green, Ky. 42101 Photojournalists document Mor~~ By JAN WI11IERSPOON MORGANTOWN - Back in side the former H and R Block building, behind. tax fonns and carpeting, behind the unassuming facade of U.S. tax bureaucracy, lurks paranoia. The pressure is waiting, hovering arOlmd students as they come into the empty bulldlng and begin a .....end of intense learning and work. Western's Sixth Annual PhototIraphy Workshop began here. Jack Com, workshop diJ"ec. tor, assembled the faculty, which included: -C. Thomas Hardin, chief photo editor and director of photography for The Courier -. Journal and The Louisv:ille Gary Halrlson, a Henderson senior, shoots his subject at Logansport grocery. Times. - Jay Dickman, 1983 - Michael Morse, Western formerly with the Dallas Prophoto of Nashville. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950. -

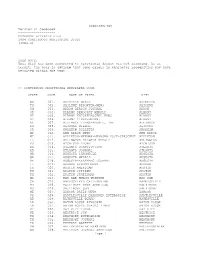

Appendix File 1984 Continuous Monitoring Study (1984.S)

appcontm.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1984 CONTINUOUS MONITORING STUDY (1984.S) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> CONTINUOUS MONITORING NEWSPAPER CODE STATE CODE NAME OF PAPER CITY WA 001. ABERDEEN WORLD ABERDEEN TX 002. ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS ABILENE OH 003. AKRON BEACON JOURNAL AKRON OR 004. ALBANY DEMOCRAT-HERALD ALBANY NY 005. ALBANY KNICKERBOCKER NEWS ALBANY NY 006. ALBANY TIMES-UNION, ALBANY NE 007. ALLIANCE TIMES-HERALD, THE ALLIANCE PA 008. ALTOONA MIRROR ALTOONA CA 009. ANAHEIM BULLETIN ANAHEIM MI 010. ANN ARBOR NEWS ANN ARBOR WI 011. APPLETON-NEENAH-MENASHA POST-CRESCENT APPLETON IL 012. ARLINGTON HEIGHTS HERALD ARLINGTON KS 013. ATCHISON GLOBE ATCHISON GA 014. ATLANTA CONSTITUTION ATLANTA GA 015. ATLANTA JOURNAL ATLANTA GA 016. AUGUSTA CHRONICLE AUGUSTA GA 017. AUGUSTA HERALD AUGUSTA ME 018. AUGUSTA-KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA IL 019. AURORA BEACON NEWS AURORA TX 020. AUSTIN AMERICAN AUSTIN TX 021. AUSTIN CITIZEN AUSTIN TX 022. AUSTIN STATESMAN AUSTIN MI 023. BAD AXE HURON TRIBUNE BAD AXE CA 024. BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIAN BAKERSFIELD MD 025. BALTIMORE NEWS AMERICAN BALTIMORE MD 026. BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE ME 027. BANGOR DAILY NEWS BANGOR OK 028. BARTLESVILLE EXAMINER-ENTERPRISE BARTLESVILLE AR 029. BATESVILLE GUARD BATESVILLE LA 030. BATON ROUGE ADVOCATE BATON ROUGE LA 031. BATON ROUGE STATES TIMES BATON ROUGE MI 032. BAY CITY TIMES BAY CITY NE 033. BEATRICE SUN BEATRICE TX 034. BEAUMONT ENTERPRISE BEAUMONT TX 035. BEAUMONT JOURNAL BEAUMONT PA 036. -

George Chaplin: W. Sprague Holden: Newbold Noyes: Howard 1(. Smith

Ieman• orts June 1971 George Chaplin: Jefferson and The Press W. Sprague Holden: The Big Ones of Australian Journalism Newbold Noyes: Ethics-What ASNE Is All About Howard 1(. Smith: The Challenge of Reporting a Changing World NEW CLASS OF NIEMAN FELLOWS APPOINTED NiemanReports VOL. XXV, No. 2 Louis M. Lyons, Editor Emeritus June 1971 -Dwight E. Sargent, Editor- -Tenney K. Lehman, Executive Editor- Editorial Board of the Society of Nieman Fellows Jack Bass Sylvan Meyer Roy M. Fisher Ray Jenkins The Charlotte Observer Miami News University of Missouri Alabama Journal George E. Amick, Jr. Robert Lasch Robert B. Frazier John Strohmeyer Trenton Times St. Louis Post-Dispatch Eugene Register-Guard Bethlehem Globe-Times William J. Woestendiek Robert Giles John J. Zakarian E. J. Paxton, Jr. Colorado Springs Sun Knight Newspapers Boston Herald Traveler Paducah Sun-Democrat Eduardo D. Lachica Smith Hempstone, Jr. Rebecca Gross Harry T. Montgomery The Philippines Herald Washington Star Lock Haven Express Associated Press James N. Standard George Chaplin Alan Barth David Kraslow The Daily Oklahoman Honolulu Advertiser Washington Post Los Angeles Times Published quarterly by the Society of Nieman Fellows from 48 Trowbridge Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138. Subscription $5 a year. Third class postage paid at Boston, Mass. "Liberty will have died a little" By Archibald Cox "Liberty will have died a little," said Harvard Law allowed to speak at Harvard-Fidel Castro, the late Mal School Prof. Archibald Cox, in pleading from the stage colm X, George Wallace, William Kunstler, and others. of Sanders Theater, Mar. 26, that radical students and Last year, in this very building, speeches were made for ex-students of Harvard permit a teach-in sponsored by physical obstruction of University activities. -

The New York Times 2014 Innovation Report

Innovation March 24, 2014 Executive Summary Innovation March 24, 2014 2 Executive Summary Introduction and Flipboard often get more traffic from Times journalism than we do. The New York Times is winning at journalism. Of all In contrast, over the last year The Times has the challenges facing a media company in the digi- watched readership fall significantly. Not only is the tal age, producing great journalism is the hardest. audience on our website shrinking but our audience Our daily report is deep, broad, smart and engaging on our smartphone apps has dipped, an extremely — and we’ve got a huge lead over the competition. worrying sign on a growing platform. At the same time, we are falling behind in a sec- Our core mission remains producing the world’s ond critical area: the art and science of getting our best journalism. But with the endless upheaval journalism to readers. We have always cared about in technology, reader habits and the entire busi- the reach and impact of our work, but we haven’t ness model, The Times needs to pursue smart new done enough to crack that code in the digital era. strategies for growing our audience. The urgency is This is where our competitors are pushing ahead only growing because digital media is getting more of us. The Washington Post and The Wall Street crowded, better funded and far more innovative. Journal have announced aggressive moves in re- The first section of this report explores in detail cent months to remake themselves for this age. First the need for the newsroom to take the lead in get- Look Media and Vox Media are creating newsrooms ting more readers to spend more time reading more custom-built for digital. -

THE NEWSGUILD – CWA 501 3Rd Street, NW, 6Th Floor, Washington, DC 20001 (202) 434-7177 Fax (202) 434-1472 Newsguild.Org

THE NEWSGUILD – CWA 501 3rd Street, NW, 6th floor, Washington, DC 20001 (202) 434-7177 Fax (202) 434-1472 newsguild.org April 30, 2020 The Honorable Dick Durbin The Honorable Tammy Duckworth United States Senate United States Senate 711 Hart Senate Office Building 524 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 Re: March 27, 2020 Letter from Heath Freeman, Alden Global Capital LLC Dear Senators Durbin and Duckworth: The NewsGuild-CWA would like to comment on the letter that Mr. Freeman wrote in response to your March 12, 2020 letter. Publicly available documents and news stories refute nearly every major claim in Freeman’s letter, which contains numerous distortions, misrepresentations, and patently false claims. Independent Journalism Mr. Freeman writes (¶ 2) that MNG Enterprises is “committed to ensuring communities across the country are served by robust, independently minded local journalism.” The fact that layoffs at MNG are twice the average in the news industry is a strange take on robust journalism and does not offer much comfort to those communities. Layoffs and furloughs have continued into the pandemic.1 NewsGuild-CWA takes issue with Freeman’s assertions of “independently minded local journalism” (¶ 3). One Colorado editor, Dave Krieger, was fired after publishing a column critical of Alden Global Capital on his own blog. At The Denver Post, opinion page editor Chuck Plunkett said he resigned because management wouldn’t let him keep publishing editorials critical of Alden’s impact on local news. Meanwhile, reporters in Kingston, NY, have been warned not to write about Alden.2 Mr.