Chapter 18. Razor Fish and Scallops

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D 6785 (L) Diary of Gilbert Mcdougall Recording His Observations of the Flora and Fauna Around Yorke Peninsula from 2 January 1886 to 16 October 1887 with an Index

_______________________________________________________________________________________ D 6785 (L) Diary of Gilbert McDougall recording his observations of the flora and fauna around Yorke Peninsula from 2 January 1886 to 16 October 1887 with an index. Transcribed by Judy Fander, Volunteer at the State Library of South Australia, 2012. Dropped out of manuscript: two watercolour drawings of two different unnamed insects on small cards. Now housed separately with the diary. Also one small drawing of a seed found between p173 and 174. On the fly leaf: J C McDougall, c/o National Bank, Adelaide Natural History Notes. 1886 Edithburgh, Y.P. Jan.2. Hunting on the rocks down at Gottschalck’s Jetty, & found several varieties of Cominella,a number of which were feeding on a dead Chiton. Several Dromiae, strange brown hairy crabs having their backs covered by a closely-fitting but unattached zoophyte ore sponge; also a couple of Chitonellus Gunni ( ), a genus of Chitonidae in which the plates are very small & narrow & imbedded at intervals along the cartilaginous back of the mollusc. Received a letter from Pulleine to whom I had sent a specimen of the black-faced Artamus which was so abundant a couple of months ago. It is the Masked Wood Swallow (Artamus personatus), a species of periodical occurrence. I have 3 good skins, & 2 eggs. The nest is si placed in similar situations to those of A. sordidus & the construction is pretty much the same, loose twigs with no lining. The male bird has a rusty red breast & is very un- Page 3. Opposite page 4 Reference date Cyclodus gigas Jan 4. -

Chapter 21. Fauna of Jetty Piles, Artificial Reefs and Biogenic Surfaces

Chapter 21. Fauna of jetties and artificial reefs CHAPTER 21. FAUNA OF JETTY PILES, ARTIFICIAL REEFS AND BIOGENIC SURFACES ALAN BUTLER C.S.I.R.O. Marine Research, Hobart, Tasmania 7001. Email: [email protected] Figure 1. Piling of Edithburgh jetty showing sponges, ascidians and bryozoans. (CAS) Introduction This chapter is not a comprehensive description or natural history of the fauna of all jetties, artificial reefs and biogenic surfaces in Gulf St Vincent (GSV) and its approaches. It is about studies done on certain jetties, etc., in the Gulf, using them as experimental systems to increase our understanding of the larger ecosystem of which they are a part. I think of the fauna attached to pilings, artificial reefs and biogenic surfaces as a window on that larger system. Pilings have been convenient places to do experiments and make repeated observations. It has to be remembered, however, that the organisms we are studying on such surfaces are part of larger populations. They have dispersive larvae which may travel short to long distances with the currents; they have predators that move about; the assemblage on one jetty is thus connected to assemblages on other jetties and reefs. We can learn a great deal by observations and experiments at the small scale, but ultimately it only makes sense if we can successfully ‘scale up’—understand these habitats in the context of the system in which they are embedded. I say more, at the end, about this ‘scaling up’. Also, the jetties etc. are artificial—a type of substratum that was not present during the millions of years of evolution of these organisms—and are, in various respects, different from their ‘natural’ habitats. -

Satellite Monitoring of Coastal Marine Ecosystems a Case from the Dominican Republic

Satellite Monitoring of Coastal Marine Ecosystems: A Case from the Dominican Republic Item Type Report Authors Stoffle, Richard W.; Halmo, David Publisher University of Arizona Download date 04/10/2021 02:16:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/272833 SATELLITE MONITORING OF COASTAL MARINE ECOSYSTEMS A CASE FROM THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Edited By Richard W. Stoffle David B. Halmo Submitted To CIESIN Consortium for International Earth Science Information Network Saginaw, Michigan Submitted From University of Arizona Environmental Research Institute of Michigan (ERIM) University of Michigan East Carolina University December, 1991 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables vi List of Figures vii List of Viewgraphs viii Acknowledgments ix CHAPTER ONE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 The Human Dimensions of Global Change 1 Global Change Research 3 Global Change Theory 4 Application of Global Change Information 4 CIESIN And Pilot Research 5 The Dominican Republic Pilot Project 5 The Site 5 The Research Team 7 Key Findings 7 CAPÍTULO UNO RESUMEN GENERAL 9 Las Dimensiones Humanas en el Cambio Global 9 La Investigación del Cambio Global 11 Teoría del Cambio Global 12 Aplicaciones de la Información del Cambio Global 13 CIESIN y la Investigación Piloto 13 El Proyecto Piloto en la República Dominicana 14 El Lugar 14 El Equipo de Investigación 15 Principales Resultados 15 CHAPTER TWO REMOTE SENSING APPLICATIONS IN THE COASTAL ZONE 17 Coastal Surveys with Remote Sensing 17 A Human Analogy 18 Remote Sensing Data 19 Aerial Photography 19 Landsat Data 20 GPS Data 22 Sonar -

16. Jetties, Shipwrecks and Other Artificial Reefs

Jetties, shipwrecks and other artificial reefs. Chapter 16 in: Baker, J.L. (2015) Marine Assets of Yorke Peninsula. Report for Natural Resources - Northern and Yorke / NY NRM Board, South Australia. 16. Jetties, Shipwrecks and Other Artificial Reefs Edithburgh Kleins Point © D. Kinasz © J. Zhang Asset Jetties, Shipwrecks and other Artificial Reefs Description Structures of wood, iron, steel, and other materials, throughout the NY NRM region, ranging from oceanographically exposed through to sheltered locations. Jetties and shipwrecks function as surfaces for attachment of marine plants and attached invertebrates; sheltering and feeding areas for fishes, sharks, rays and invertebrates; and as “fish-attracting” devices, periodically visited by schooling fishes which are attracted to vertical structure. Surrounding sea floor varies according to the location of the jetty or wreck, and includes reef, seagrass, sand, and rubble. There are also two purpose-built artificial reefs in the NY NRM region, constructed of tetrahedon module units, made up vehicle tyres. Main Species Sponges sponges (numerous species, in genera Dysidea, Euryspongia, Darwinella, Aplysilla, Dendrilla, Clathrina and many others) Ascidians / Sea Squirts Red-mouthed Ascidian, Obese Ascidian, and other solitary ascidians / sea squirts Brain Ascidian, and other colonial ascidians Spongy Compound, Leach’s Compound & other compound ascidians Corals gorgonian corals such as Mopsella zimmeri (on current-exposed jetties) soft corals, such as Carijoa (also Drifa sp. on current-exposed jetties) solitary coral Scolymia Bryozoans various species, including various species in Cellaporaria (such as Orange Plate Bryozoan and Nipple Bryozoan) and species in Triphyllozoon (Lace Bryozoans) Gastropod Shells Cowries, Cartrut shell, Triton shells Bivalve Shells Doughboy Scallop, Razorfish Shell, juvenile Native Oyster Jetties, shipwrecks and other artificial reefs. -

Mike Makatron

MIKE MAKATRON Mike Maka was born in the Yorke Peninsula to the large Moloney clan of 12 siblings. Their farm for over 80 years in Arthurton still runs in the family to this day, with two of Mikes Uncles working the land. With a close connection to the Yorke Peninsula, Mike proposes the following concept for Edithburgh. Edithburgh Concept: The Edithburgh concept begins with a wide array of coral sourced from underwater photography of the local jetty, as well as a Striped Pyjama Squid, a Cuttlefish and the magnificent Leafy Sea Dragon. Contrasting the deep blue of the surf in the bottom section, the top of the work features a radiant sunrise backgrounding the White Bellied Sea Eagle and the endangered Far Eastern Curlew in dynamic stages of flight as well as the Troubridge Island lighthouse darting up from the swell. Adorned with a subtle reference to 1856 establishment at the base. Edithburgh Design Concept: (to scale/flat) EDITHBURGH RESPONSE: For the Edithburgh water tower I have chosen to propose a design that celebrates the magnificent marine life beneath Edithburgh Jetty. Rich and buzzing natural hubs like the underwater garden at Edithburgh Jetty are increasingly rare and more essential than ever. Not only is this a bold, colourful and iconic landmark, it’s also one that demonstrates importance for the visibility and appreciation of Yorke Peninsula’s lively sea environment. Not only will the mural locate and reference a unique natural wonder of Edithburgh, the curved surface of the tower itself will also be utilised in visually imitating the cylindrical Edithburgh Jetty pylons that harbour the colourful sea sponges and marine life. -

Nacre Tablet Thickness Records Formation Temperature in Modern and Fossil Shells

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title Nacre tablet thickness records formation temperature in modern and fossil shells Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1rf2g647 Authors Gilbert, PUPA Bergmann, KD Myers, CE et al. Publication Date 2017-02-15 DOI 10.1016/j.epsl.2016.11.012 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bivalve nacre preserves a physical indicator of paleotemperature Pupa U.P.A Gilbert1,2*, Kristin D. Bergmann3,4, Corinne E. Myers5,6, Ross T. DeVol1, Chang-Yu Sun1, A.Z. Blonsky1, Jessica Zhao2, Elizabeth A. Karan2, Erik Tamre2, Nobumichi Tamura7, Matthew A. Marcus7, Anthony J. Giuffre1, Sarah Lemer5, Gonzalo Giribet5, John M. Eiler8, Andrew H. Knoll3,5 1 University of Wisconsin–Madison, Department of Physics, Madison WI 53706 USA. 2 Harvard University, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Fellowship Program, Cambridge, MA 02138. 3 Harvard University, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Cambridge, MA 02138. 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Cambridge, MA 02138. 5 Harvard University, Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Cambridge, MA 02138. 6 University of New Mexico, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Albuquerque, NM 87131. 7 Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, 94720, USA. 8 California Institute of Technology, Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, Pasadena, CA 91125 * [email protected], previously publishing as Gelsomina De Stasio Abstract: Biomineralizing organisms record chemical information as they build structure, but to date chemical and structural data have been linked in only the most rudimentary of ways. In paleoclimate studies, physical structure is commonly evaluated for evidence of alteration, constraining geochemical interpretation. -

2003 109.Pdf

No. 109 4031 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE www.governmentgazette.sa.gov.au PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 13 NOVEMBER 2003 CONTENTS Page Page Acts Assented To.....................................................................4032 Proclamations.......................................................................... 4048 Appointments, Resignations, Etc.............................................4032 Public Trustee Office—Administration of Estates .................. 4060 Aquaculture Act 2001—Notices .............................................4033 Corporations and District Councils—Notices .........................4059 REGULATIONS Development Act 1993—Notices............................................4034 Aquaculture (Fees) Variation Regulations 2003 Electricity Act 1996—Notice..................................................4035 (No. 226 of 2003) ............................................................ 4053 Fisheries Act 1982—Notices...................................................4036 Native Vegetation Variation Regulations 2003 Food Act 2001—Notice ..........................................................4037 (No. 227 of 2003) ............................................................ 4055 Land and Business (Sale and Conveyancing) Act 1994 Roads (Opening and Closing) Act 1991—Notices.................. 4044 Notice ..................................................................................4037 Sale of -

Revision of the Monacanthid Fish Genus Brachaluteres

Rec. West. Aust. Mus. 1985, 12 (1): 57-78 Revision of the Monacanthid Fish Genus Brachaluteres J. Barry llutchins* and Roger Swainston* Abstract Four species of the monacanthid genus Brachaluteres are recognised: B. jack sonianus (Quoy and Gaimard) from southern Australia; B. taylori Woods from Queensland, Lord Howe Island, New Guinea and the Marshall Islands; B. ulvarum Jordan and Snyder from Japan; and B. fahaqa Clark and Gohar from the Red Sea. The long accepted name of B. baueri (Richardson) is shown to be ajunior synonym of B. jacksonianus. A key to the species is provided, as well as diagnostic illus trations. Introduction The monacanthid genus Brachaluteres consists of small fishes which are known from shallow inshore waters of several areas in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. They are reasonably common in Australia and Japan, but records for the Marshall Islands, Papua New Guinea, the Maldives and the Red Sea are each based on one to three specimens only. Being poor swimmers, they are usually found on shel tered reefs, in sea grasses or around jetty piles. All members of the genus can greatly inflate their abdomens when in danger, an adaptation which serves to noticeably increase their body size (Figure 1). This feature, together with their cryptic coloration, probably decreases the chances of predation, and therefore compensates for their relatively poor swimming ability. The genus has not been reviewed previously, although species lists and/or species accounts were presented by Gunther (1870), MacIeay (1881), McCulloch, (1929), Fraser-Brunner (1941), Clark and Gohar (1953), Whitley (1964), Woods (1966) and Scott (1969). -

Zootaxa, Mollusca, Vetigastropoda

ZOOTAXA 714 New species of Australian Scissurellidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda) with remarks on Australian and Indo-Malayan species DANIEL L. GEIGER & PATTY JANSEN Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand DANIEL L. GEIGER & PATTY JANSEN New species of Australian Scissurellidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda) with remarks on Australian and Indo-Malayan species (Zootaxa 714) 72 pp.; 30 cm. 4 November 2004 ISBN 1-877354-66-X (Paperback) ISBN 1-877354-67-8 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2004 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2004 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 714: 1–72 (2004) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 714 Copyright © 2004 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) New species of Australian Scissurellidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda) with remarks on Australian and Indo-Malayan species DANIEL L. GEIGER1 & PATTY JANSEN2 1 Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, 2559 Puesta del Sol Road, Santa Barbara, CA 93105, USA. E- mail: [email protected] 2 P. O. Box 345, Lindfield, NSW 2070, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] Table of contents Abstract . -

Distinción Taxonómica De Los Moluscos De Fondos Blandos Del Golfo De Batabanó, Cuba

Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res., 43(5): 856-872, 2015Distinción taxonómica de los moluscos del Golfo de Batabanó, Cuba 856 1 DOI: 10.3856/vol43-issue5-fulltext-6 Research Article Distinción taxonómica de los moluscos de fondos blandos del Golfo de Batabanó, Cuba Norberto Capetillo-Piñar1, Marcial Trinidad Villalejo-Fuerte1 & Arturo Tripp-Quezada1 1Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional P.O. Box 592, La Paz, 23096 Baja California Sur, México Corresponding author: Arturo Tripp-Quezada ([email protected]) RESUMEN. La distinción taxonómica es una medida de diversidad que presenta una serie de ventajas que dan connotación relevante a la ecología teórica y aplicada. La utilidad de este tipo de medida como otro método para evaluar la biodiversidad de los ecosistemas marinos bentónicos de fondos blandos del Golfo de Batabanó (Cuba) se comprobó mediante el uso de los índices de distinción taxonómica promedio (Delta+) y la variación en la distinción taxonómica (Lambda+) de las comunidades de moluscos. Para este propósito, se utilizaron los inventarios de especies de moluscos bentónicos de fondos blandos obtenidos en el periodo 1981-1985 y en los años 2004 y 2007. Ambos listados de especies fueron analizados y comparados a escala espacial y temporal. La composición taxonómica entre el periodo y años estudiados se conformó de 3 clases, 20 órdenes, 60 familias, 137 géneros y 182 especies, observándose, excepto en el nivel de clase, una disminución no significativa de esta composición en 2004 y 2007. A escala espacial se detectó una disminución significativa en la riqueza taxonómica en el 2004. No se detectaron diferencias significativas en Delta+ y Lambda+ a escala temporal, pero si a escala espacial, hecho que se puede atribuir al efecto combinado del incremento de las actividades antropogénicas en la región con los efectos inducidos por los huracanes. -

A Revision of the Australian Pinnidae

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Hedley, Charles, 1924. A revision of the Australian Pinnidae. Records of the Australian Museum 14(3): 141–153, plates xix–xxi. [26 June 1924]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.14.1924.838 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney nature culture discover Australian Museum science is freely accessible online at http://publications.australianmuseum.net.au 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia A REVISION OF THE AUSTRALIAN PINNIDJE. By CHARLES HEDLEY. (Plates xix-xxi.) The Pinnidm are a small family of marine bivalves including many fossil and about fifty recent species which occur throughout the warmer seas of the world. Though thin and brittle these shells are notable for their length, being exceeded in this respect only by the Giant Clams. They live planted point downwards with the tips of the broad ends projecting above the surface of zostera flats. An ugly wound may be inflicted on the bare feet of those who tread on their sharp blades, from this the shells are called in Australia "Razorbacks." The doings of a commensal crab, Pinnotheres, frequently a guest in the Pinna mansion, is related by classic legends either as the behaviour of a rascal or of a grateful attendant. The first attempt at classification of the Pinnidm was by Chemnitz, who in 1785 drew attention to a feature separating various species of Pinna,. In some, for instance P. ineurv1ata., the apical muscle scar has a ridge running lengthwise down the centre; in others, as in P. atrata, this ridge is absent. Apparently prompted by this observa tion, Gray proposed' the genus Atrina for the second group, with P. -

Wfdwa-Rsl-181112

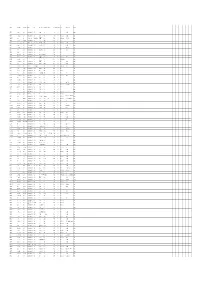

SURNAME FIRST NAMES RANK at Death REGIMENT UNIT WHERE BORN BORN STATE HONOURS DOD (DD MMM) YOD (YYYY) COD PLACE OF DEATH COUNTRY A'HEARN Edward John Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Wilcannia NSW 4 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium AARONS John Fullarton Private Australian Infantry, AIF 16th Bn Hillston NSW 11 Jul 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France Manchester, ABBERTON Edmund Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Div Signal Coy England 6 Nov 1918 DOI (Illness, acute) 1 AAH, Harefield England Lancashire ABBOTT Charles Edgar Lance Corporal Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Avoca Victoria 30 May 1916 KIA - France ABBOTT Charles Henry Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Tunnelling Coy Maryborough Victoria 26 May 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France ABBOTT Henry Edgar Private Australian Army Medical Corp10th AFA Burra or Hoylton SA 12 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium ABBOTT Oliver Oswald Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Hoyleton SA 22 Aug 1916 KIA Mouquet Farm France ABBOTT Robert Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Malton, Yorkshire England 25 Jul 1916 KIA France France ABOLIN Martin Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Riga Russia 10 Jun 1917 KIA - Belgium ABRAHAM William Strong Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Mepunga, WarnnamboVictoria 25 Jul 1916 KIA - France Southport, ABRAM Richard Private Australian Infantry, AIF 28th Bn England 29 Jul 1916 Declared KIA Pozieres France Lancashire ACKLAND George Henry Private Royal Warwickshireshire Reg14th Bn N/A N/A 8 Feb 1919 DOI (Illness, acute) - England Manchester, ACKROYD