University of Southampton Research Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undergraduate Admission Guidebook for 2021/2022 Academic Year (For Holders of Ordinary Diploma Or Equivalent Qualifications)

Tanzania Commission for Universities (TCU) Undergraduate Admission Guidebook for 2021/2022 Academic Year (For Holders of Ordinary Diploma or Equivalent Qualifications) May, 2021 © Tanzania Commission for Universities (TCU), 2020 P.O. Box 6562, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Tel.: +255-22-2113694; Fax +255-22-2113692 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Website: www.tcu.go.tz Hotline Numbers: +255 765 027 990; +255 674 656 237; +255 683 921 928 Physical Address: 7 Magogoni Street, 11479 Dar es Salaam ISBN: 978 -9976 – 9353 – 1 - 4 ii Undergraduate Admission Guidebook for 2021/2022 Academic Year (For Holders of Ordinary Diploma or Equivalent Qualifications) Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................................. iii Preface ................................................................................................................................................................................. vii 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Entry Schemes into Degree Programmes ................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Admission Procedure .......................................................................................................................................... 1 2.3 Higher -

Tuma Prospectus

TUMAINI UNIVERSITY MAKUMIRA PROSPECTUS 2018 – 2021 University Training for Service and Leadership TumainiUniversityMakumira P.O. Box 55, Usa - River Arumeru District Arusha, Tanzania Tel +255-27-2541034/36 Fax +255-27-2541030 E-mail: [email protected] Registrar: [email protected] Website: www.makumira.ac.tz This prospectus is intended to provide information to any party interested in the Tumaini University Makumira. It does not constitute a contract of any kind between the Tumaini University Makumira and the interested party. It was compiled on the basis of available information at the time of its preparation and is therefore, subject to change at any time without notice or obligation. © TUMAINI UNIVERSITY MAKUMIRA 2018 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE VICE CHANCELLOR...............1 VISION, MISSION, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES OF TUMAINI UNIVERSITY MAKUMIRA.........................2 The Vision of the University..............................................2 The Mission of the University...........................................2 The Objectives of the University......................................2 Strategies of the University..............................................3 Core Values of the University...........................................3 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND..................................4 STUDENT LIFE.....................................................5 Students’ Government.....................................................5 University Hostels............................................................5 Family -

Downloaded and Processed to Produce Bouguer Anomaly

TANZANIA GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY (TGS) 2018 ANNUAL MEETING AND WORKSHOP BOOK OF ABSTRACTS DODOMA th nd 27 September to 2 October 2018 Front cover photos: Top Left: Dodoma City - the national capital of the United Republic of Tanzania (Picture source: https://www.tripindigo.com/blog/things-to-do-in-dodoma/). The name Dodoma literally means "It has sunk" in Gogo, one of the languages spoken in Dodoma; Top Right: Mtera Dam – hydroelectric dam located midway between Iringa and Dodoma regions on the border between the Iringa Region and the Dodoma Region. It measures 660 square kilometers and is feed by the Great Ruaha River and the Kisigo River; Bottom left: Mwl. Julius Kambarage Nyerere's statue in Nyerere Square Dodoma; and Bottom right: The Kondoa Irangi Rock Paintings one of the series of ancient paintings on rock shelter walls in central Tanzania, recognized as one of the UNESCO World Heritage sites. Message to Participants of the TGS 2018 Workshop Dear Participants, Welcome to the Tanzania Geological Society (TGS) 2018 annual geoscientific workshop and meeting to be held here in the Dodoma city from 27th of September 2018 to 2nd of October 2018. The event is anticipated to provide a timely opportunity to bring together geoscience stakeholders including members of the industry, academia, policy makers and related agencies from all over the country and beyond. For this TGS colloquium, we received over 50 Abstracts, all converging to this year’s main theme “The role of geoscientists in the Tanzania Industrial Development”. The received abstracts are subdivided into 8 sub-themes as narrated below: 1. -

Prospectus 2016/2017

MINERAL RESOURCES INSTITUTE (MRI) P. O. Box 1696, Dodoma, Tanzania Telephone/Fax: +255 (0) 26 23 00 472 / +255 (0) 26 23 03 159 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Website: www.mri.ac.tz PROSPECTUS 2016/2017 August, 2016 Prospectus 2016/2017 i FORWORD We are very pleased to welcome you to undertake tertiary studies at The Mineral Resources Institute (MRI). This Prospectus will provide you with a flavour of academic life in our Institution. The Mineral Resources Institute (MRI) is an institution of Earth Sciences Education which was established by the former Ministry of Minerals in Dodoma in August, 1982. It is fully accredited by the National Council for Technical Education (NACTE) to offer Geology and Mineral Exploration, mining engineering, Petroleum Geoscience, Mineral Processing Engineering and Environmental Engineering and Management in Mines programmes leading to the qualifications of National Technical Awards (NTA) level 4 – 6. NTA level 4 programmes lead to Basic Technician Certificate, NTA level 5 programme lead to Technician Certificate and NTA level 6 programme lead to Ordinary Diploma Certificate. Along with the introduction of the new curricula, the previous curricula leading to Mineral Resources Technology Certificate and Full Technician Certificate in Earth Sciences have already been phased out. With the cooperation of main stakeholders under the auspices of the Ministry of Energy and Minerals (MEM), the Institute is still undergoing transformation to match with the envisaged expectations and aspirations of the Tanzania. Our ultimate goal is to transform our institution to be the best academic institution in Africa in 25 years from 2012 in areas of quality training in mining sector including gemology and petroleum sciences; quality research in geological sciences and mining related sciences and quality consultancy and provisional of sound short courses. -

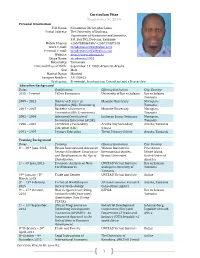

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae September 9, 2016 Personal Information Full Name: Nicodemas Christopher Lema Postal Address: The University of Dodoma, Department of Economics and Statistics, P.O. Box 395, Dodoma, Tanzania Mobile Phones: +255753836430/ +255719337243 Work E-mail: [email protected] Personal E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.udom.ac.tz Skype Name: nicodemasc2002 Nationality: Tanzanian Date and Place of Birth: September 11, 1983; Arumeru, Arusha. Sex: Male Marital Status: Married Passport Number: AB 180422 Profession: Economist, Academician, Consultant and a Researcher Education Background Dates Qualification Offering Institution City, Country 2015 – Present PhD in Economics University of Dar es Salaam Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 2009 – 2011 Master of Science in Mzumbe University Morogoro, Economics (MSc. Economics) Tanzania 2004 – 2007 Bachelor of Science in Mzumbe University Morogoro, Economics (BSc. Economics) Tanzania 2002 – 2004 Advanced Certificate of Lutheran Junior Seminary Morogoro, Secondary Education (ACSE) Tanzania 1998 – 2001 Certificate of Secondary Arusha Day Secondary Arusha, Tanzania Education (CSE) School 1991 – 1997 Primary Education Themi Primary School Arusha, Tanzania Training Background Dates Training Offering Institution City, Country 6th – 20 th June, 2015 Brown International Advanced Watson Institute for Providence – Research Institute: Governance International Studies, Rhode Island, and Development in the Age of Brown University United States of Globalization. America 1st – 4th June, 2015 -

Engineers' Accreditation and Mobility in Tanzania and East Africa

Engineers’ Accreditation and Mobility in Tanzania and East Africa A paper presented at the High Level Policy Forum on Engineering Accreditation and Mobility in Africa, July 18, 2016, Abuja, Nigeria By Eng. Benedict Mukama Assistant Registrar-Professional Development Affairs Engineers Registration Board - Tanzania Abstract Pursuant Sect.7(1)-(6) of the Act, the Engineers Registration Board ( ERB) is mandated in collaboration with the Tanzania Commission for Universities to accredit engineering programmes. The Mutual Recognition Agreement for EAC countries also recognizes engineering programmes accredited by Competent Authorities (engineering regulatory bodies) of the partner states. This paper narrates the accreditation process in Tanzania and the mutual recognition of engineering programmes and qualifications which is a gateway for facilitating the mobility of engineers in the East African partner states. 1. Introduction The East African Community (EAC) is made of 6 countries namely Tanzania, Kenya , Uganda, Rwanda , Burundi and Southern Sudan with a poulation of about 170,000,000 and a total of about 30,000 engineers. The Southern Sudan joined the community recently on 2nd March 2016 In Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda the accreditation of engineering programmes falls under the jurisdiction of the respective competent authorities of the East African countries namely the Engineers Registration Board, the Engineers Board of Kenya, and the Engineers Registration Board of Uganda and respectively the . The three EAC countries namely Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda signed the Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) on 7th December 2012 in order to facilitate free movement of engineers in the region. Rwanda signed on 1st March 2016 whereas Burundi is yet to sign the agreement after putting in placeall professional regulatory requirements as recommended by the regional body. -

Tanzania Commission for Universities

Tanzania Commission for Universities List of Approved University Institutions in Tanzania as of 4th February, 2019 Tanzania Commission for Universities List of Approved University Institutions in Tanzania as of 4th February, 2019 1: FULLY FLEDGED UNIVERSITIES 1A: Public Universities Approved SN Name of the University Head Office Current Status Acronym 1. University of Dar es Salaam UDSM Dar es Salaam Accredited and Chartered 2. Sokoine University of Agriculture SUA Morogoro Accredited and Chartered 3. Open University of Tanzania OUT Dar es Salaam Accredited and Chartered 4. Ardhi University ARU Dar es Salaam Accredited and Chartered Certificate of Full 5. State University of Zanzibar SUZA Zanzibar Registration (CFR) 6. Mzumbe University MU Morogoro Accredited and Chartered Muhimbili University of Health & 7. MUHAS Dar es Salaam Accredited and Chartered Allied Sciences Certificate of Full Nelson Mandela African Institute of 8. NMAIST Arusha Registration (CFR) and Science and Technology Chartered Certificate of Full 9. University of Dodoma UDOM Dodoma Registration (CFR) and Chartered Certificate of Full Mbeya University of Science and 10. MUST Mbeya Registration (CFR) and Technology Chartered Certificate of Full 11. Moshi Cooperative University MoCU Moshi Registration (CFR) and Chartered Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere University 12. MJNUAT Musoma Provisional Licence1 of Agriculture and Technology 1 1B: Private Universities Approved SN Name of the University Head Office Current Status Acronym 1. Hubert Kairuki Memorial University HKMU Dar es Salaam Accredited and Chartered International Medical and Certificate of Full Registration 2. Technological University and IMTU Dar es Salaam (CFR) and Chartered Chartered 3. Tumaini University Makumira TUMA Arusha Accredited and Chartered 4. St. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Higher Education for Economic Transformation Project (P166415) Public Disclosure Authorized For Official Use Only Public Disclosure Authorized Concept Environmental and Social Review Summary Concept Stage (ESRS Concept Stage) Date Prepared/Updated: 12/07/2020 | Report No: ESRSC01662 Public Disclosure Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Dec 07, 2020 Page 1 of 17 The World Bank Higher Education for Economic Transformation Project (P166415) BASIC INFORMATION A. Basic Project Data Country Region Project ID Parent Project ID (if any) Tanzania AFRICA EAST P166415 Project Name Higher Education for Economic Transformation Project Practice Area (Lead) Financing Instrument Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Education Investment Project 1/4/2021 2/24/2021 Financing For Official Use Only Borrower(s) Implementing Agency(ies) Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Education, Planning Science and Technology Proposed Development Objective To strengthen the learning environments and labor market alignment of programs in priority areas and the management of the higher education system. Financing (in USD Million) Amount Public Disclosure Total Project Cost 300.00 B. Is the project being prepared in a Situation of Urgent Need of Assistance or Capacity Constraints, as per Bank IPF Policy, para. 12? No C. Summary Description of Proposed Project [including overview of Country, Sectoral & Institutional Contexts and Relationship to CPF] The project will help strengthen: (i) the capacity and quality of select universities to prepare faculty, researchers, graduates, and to build a strong and flexible, high skilled workforce that can address Tanzania’s development challenges; and (ii) the capacity of supervising agencies to oversee the entire higher education system (both, public and private) in a fiscally sustainable and quality-improving manner. -

Impact of Higher Learning Institutions Expansion on The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Library of Open University of Tanzania IMPACT OF HIGHER LEARNING INSTITUTIONS EXPANSION ON THE ADEQUACY OF NETWORK INFRASTRUCTURE IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: A CASE OF ICT PLANNING AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DODOMA AHMED SALIM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT OF THE OPEN UNIVERSITY OF TANZANIA 2016 ii CERTIFICATION The undersigned certifies that he has read and hereby recommends for acceptance by the Open University of Tanzania a dissertation entitled “Impact of Higher Learning Institutions Expansion on the Adequacy of Network Infrastructure in Developing Countries: A Case of ICT Planning at the University of Dodoma” in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Project Management (MPM) of the Open University of Tanzania. .................................................……… Dr. Cosmas B.M. Haule Supervisor ............................................................ Date iii COPYRIGHT No part of this dissertation maybe submitted or reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the author or The Open University of Tanzania in that behalf. iv DECLARATION I, Ahmed Salim, do hereby declare that this dissertation is my own original work and that it has not been presented and will not be presented to any university for similar or any other degree award. ………………………………………… Signature ………………………………………… Date v COPYRIGHT No part of the dissertation may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the author or the Open University of Tanzania in that behalf. -

Country Fact Sheet Tanzania

Country Fact Sheet Tanzania Table of contents Foreword 4 List of abbreviations 5 Statistics 7 Country Map 8 1. Country Profile 9 1.1 Geographical Presentation 9 1.2 Socio-demographic Analysis 10 1.3 Political Context 12 1.4 Economic Performance – synthesis 12 1.5 Development challenges 13 2. Education 15 2.1 Structure 15 2.1.1 The structure of Tanzania’s education system 15 2.1.2 Management and Administration of Education 16 2.2 Data and Policy focus in terms of higher education 16 3. Development Aid Analysis 19 3.1 Development strategy with focus on poverty reduction 19 3.2 Actors 20 3.3 Donor Aid 20 4. University Development Cooperation 23 4.1 VLIR-UOS Activity in/with the Country 23 4.2 Focus of other university development cooperation donors 24 List of Resources and interesting Links 27 ANNEXES 28 A. PRSP 28 B. Strategy Papers of the Ministry of Higher Education 28 Country Fact Sheet Tanzania 2 C. List of HE Institutes (private <-> public) and their focal points 28 Country Fact Sheet Tanzania 3 Foreword The Country Sheet Tanzania is a compilation of information from related documents with factual country information, economic, social and development priorities, with also information on higher education and university cooperation in Tanzania. The information included is extracted from policy documents, websites and strategy papers from EU, UNDP, worldbank and other organisations. Contextual information from the 2008 end term evaluation of the IUC with Sokoine Agricultural University (SUA) , performed by S. Mantell and O. Abagi (international consultants) was also included. -

Undergraduate Admission Guidebook for Higher Education Institutions in Tanzania

Undergraduate Admission Guidebook for Higher Education Institutions in Tanzania Tanzania Commission for Universities Undergraduate Students Admission Guidebook for Higher Education Institutions in Tanzania 2015/2016 i Undergraduate Admission Guidebook for Higher Education Institutions in Tanzania Tanzania Commission for Universities (TCU) P.O. Box 6562, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Tel. +255-22-2772657; Fax +255-22-2772891 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected]; Website: www.tcu.go.tz Hotline Numbers: +255 765 027 990, +255 674 656 237 and +255 683 921 928 Physical Address: Garden Road, Mikocheni (near TPDC Estate), Dar es Salaam ISBN: 978 -9976 – 9353 – 1 - 4 ii Undergraduate Admission Guidebook for Higher Education Institutions in Tanzania Abbreviations ACSEE Advanced Certificate of Secondary Education Examination CAS Central Admission System CSEE Certificate of Secondary Education Examination FTC Full Technician Certificate HESLB Higher Education Students’ Loans Board NACTE National Council for Technical Education NBAA National Board of Accountants and Auditors NBC National Bank of Commerce NBMM National Board for Materials Management NECTA National Examinations Council of Tanzania NTA National Technical Award NVA National Vocational Award UQF University Qualifications Framework ODL Open and Distance Learning PSPTB Procurement and Supplies Professionals and Technicians Board RPL Recognition of Prior Learning SMS Short Message Service TCU Tanzania Commission for Universities VETA Vocational Education and Training Authority iii Undergraduate Admission Guidebook for Higher Education Institutions in Tanzania Table of Contents Content Page Preface 1 1. Introduction 2 2. Important dates 2 3. Admission into Higher Education Institutions and mode of payment 3 4. Types of higher education delivery modes. 5 5. -

Research4life Academic Institutions

Research4Life Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University HERAT HERAT UNIVERSITY Herat Institute of Health Sciences Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Alfalah University Kabul Afghan Medical College Kabul 20-Apr-2018 9:40 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 174 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul JUNIPER MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGE Government Medical College Kabul University. Faculty of Veterinary Science Aga Khan University Programs in Afghanistan (AKU-PA) Kabul Dental College, Kabul Kabul University. Central Library American University of Afghanistan Agricultural University of Afghanistan Kabul Polytechnic University Kabul Education University Kabul Medical University, Public Health Faculty Cheragh Medical Institute Kateb University Prof. Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences Khatam al Nabieen University Kabul Medical University Kandahar Kandahar University Malalay Institute of Higher Education Kapisa Alberoni University khost,city Shaikh Zayed University, Khost 20-Apr-2018 9:40 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 174 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Lashkar Gah Helmand University Logar province Logar University Maidan Shar Community Midwifery School Makassar Hasanuddin University Mazar-e-Sharif Aria Institute of Higher Education, Faculty of Medicine Balkh Medical Faculty Pol-e-Khumri Baghlan University Samangan Samanagan University Sheberghan Jawzjan university Albania Elbasan University "Aleksander Xhuvani" (Elbasan), Faculty of Technical Medical Sciences Korca Fan S. Noli University, School of Nursing Tirana University of Tirana Agricultural University of Tirana 20-Apr-2018 9:40 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 3 of 174 Country City Institution Name Albania Tirana University of Tirana.