SATIRE, COMEDY and MENTAL HEALTH Coping with the Limits of Critique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Queer" Third Species": Tragicomedy in Contemporary

The Queer “Third Species”: Tragicomedy in Contemporary LGBTQ American Literature and Television A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Lindsey Kurz, B.A., M.A. March 2018 Committee Chair: Dr. Beth Ash Committee Members: Dr. Lisa Hogeland, Dr. Deborah Meem Abstract This dissertation focuses on the recent popularity of the tragicomedy as a genre for representing queer lives in late-twentieth and twenty-first century America. I argue that the tragicomedy allows for a nuanced portrayal of queer identity because it recognizes the systemic and personal “tragedies” faced by LGBTQ people (discrimination, inadequate legal protection, familial exile, the AIDS epidemic, et cetera), but also acknowledges that even in struggle, in real life and in art, there is humor and comedy. I contend that the contemporary tragicomedy works to depart from the dominant late-nineteenth and twentieth-century trope of queer people as either tragic figures (sick, suicidal, self-loathing) or comedic relief characters by showing complex characters that experience both tragedy and comedy and are themselves both serious and humorous. Building off Verna A. Foster’s 2004 book The Name and Nature of Tragicomedy, I argue that contemporary examples of the tragicomedy share generic characteristics with tragicomedies from previous eras (most notably the Renaissance and modern period), but have also evolved in important ways to work for queer authors. The contemporary tragicomedy, as used by queer authors, mixes comedy and tragedy throughout the text but ultimately ends in “comedy” (meaning the characters survive the tragedies in the text and are optimistic for the future). -

Middle Comedy: Not Only Mythology and Food

Acta Ant. Hung. 56, 2016, 421–433 DOI: 10.1556/068.2016.56.4.2 VIRGINIA MASTELLARI MIDDLE COMEDY: NOT ONLY MYTHOLOGY AND FOOD View metadata, citation and similar papersTHE at core.ac.ukPOLITICAL AND CONTEMPORARY DIMENSION brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Summary: The disappearance of the political and contemporary dimension in the production after Aris- tophanes is a false belief that has been shared for a long time, together with the assumption that Middle Comedy – the transitional period between archaia and nea – was only about mythological burlesque and food. The misleading idea has surely risen because of the main source of the comic fragments: Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters. However, the contemporary and political aspect emerges again in the 4th c. BC in the creations of a small group of dramatists, among whom Timocles, Mnesimachus and Heniochus stand out (significantly, most of them are concentrated in the time of the Macedonian expansion). Firstly Timocles, in whose fragments the personal mockery, the onomasti komodein, is still present and sharp, often against contemporary political leaders (cf. frr. 17, 19, 27 K.–A.). Then, Mnesimachus (Φίλιππος, frr. 7–10 K.–A.) and Heniochus (fr. 5 K.–A.), who show an anti- and a pro-Macedonian attitude, respec- tively. The present paper analyses the use of the political and contemporary element in Middle Comedy and the main differences between the poets named and Aristophanes, trying to sketch the evolution of the genre, the points of contact and the new tendencies. Key words: Middle Comedy, Politics, Onomasti komodein For many years, what is known as the “food fallacy”1 has been widespread among scholars of Comedy. -

Stand-Up Comedy and the Clash of Gendered Cultural Norms

Stand-up Comedy and the Clash of Gendered Cultural Norms The Honors Program Honors Thesis Student’s Name: Marlee O’Keefe Faculty Advisor: Amber Day April 2019 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 1 LITERATURE REVIEW.......................................................................................................... 2 COMEDY THEORY LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................. 2 GENDER THEORY LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................... 7 GENDERED CULTURAL NORMS ...................................................................................... 13 COMEDY THEORY BACKGROUND ................................................................................. 13 COMEDIANS ......................................................................................................................... 16 STEREOTYPES ..................................................................................................................... 20 STAND-UP SPECIALS/TYPES OF JOKES ......................................................................... 25 ROLE REVERSAL ............................................................................................................. 25 SARCASAM ....................................................................................................................... 27 CULTURAL COMPARISON: EXPECTATION VERSUS REALITY ........................... -

Stand-Up Comedy in Theory, Or, Abjection in America John Limon 6030 Limon / STAND up COMEDY / Sheet 1 of 160

Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America John Limon Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 1 of 160 Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 2 of 160 New Americanists A series edited by Donald E. Pease Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 3 of 160 John Limon Duke University Press Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America Durham and London 2000 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 4 of 160 The chapter ‘‘Analytic of the Ridiculous’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in Raritan: A Quarterly Review 14, no. 3 (winter 1997). The chapter ‘‘Journey to the End of the Night’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in Jx: A Journal in Culture and Criticism 1, no. 1 (autumn 1996). The chapter ‘‘Nectarines’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in the Yale Journal of Criticism 10, no. 1 (spring 1997). © 2000 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ! Typeset in Melior by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 5 of 160 Contents Introduction. Approximations, Apologies, Acknowledgments 1 1. Inrage: A Lenny Bruce Joke and the Topography of Stand-Up 11 2. Nectarines: Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks 28 3. -

Laughing at Power, Fascism, and Authoritarianism: Satire, Humor, Irony, and Interrogating Their Political Efficacy

Laughing at Power, Fascism, and Authoritarianism: Satire, Humor, Irony, and Interrogating Their Political Efficacy April 8-10, 2018 Center for Jewish History New York City Abstract deadline: September 1, 2017 Response by: October 1, 2017 Projects to be workshopped deadline: March 1, 2018 Satire, humor, and irony have served as powerful weapons against totalitarianism and other forms of authoritarianism and authoritarian leaders. Before Hitler was scary, he was considered a joke, someone to be laughed at. During World War II, journalists, artists, writers and film-makers around the globe, used their golden pens, cameras, and paintbrushes to create powerful weapons against fascism. Some of them lived in the relative safety of United States or China, others were in the midst of it all, in Polish ghettos, occupied parts of the Soviet Union, or hiding in French villages. Today we understand these works both as effective forms of resistance and powerful means of making sense of the incomprehensive historical events. Studying satirical films, cabarets, comedy routines, music, cartoons, caricatures, and jokes as historical sources reveals details of the zeitgeist of the time, simply unavailable from other sources. At the same time, humor is limited in its ability to effect politics. While someone could laugh at Hitler, Hitler could not be stopped only through laughter. The workshop, jointly hosted by the journal East European Jewish Affairs and the Center for Jewish History and sponsored by the University of Colorado’s Singer Fund for Jewish Studies, proposes a new way of thinking about humor and resistance by bringing together scholars, artists, musicians, and comedians, and use both scholarly methods of textual analysis and artistic imagination to work on uncovering how fascism was fought not with the sword, but with laughter, satire, and irony and a healthy dose of political organizing. -

THEATRE, DRAMA, HUMOR, and COMEDY: by Don L. F. Nilsen English Department Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-0302 ( Don.Ni

THEATRE, DRAMA, HUMOR, AND COMEDY: by Don L. F. Nilsen English Department Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287-0302 ( [email protected] ) Alexander, D. "Political Satire in the Israeli Theatre: Another Outlook on Zionism." Jewish Humor. Ed. Avner Ziv. Tel Aviv, Israel: Papyrus, 1986, 165-74. Appell, Virginia. "Acts of the Comedic Art: The Frantics on Stage." Play and Culture 1.3 (August, 1988): 239- 46. Apte, Mahadev L. Humor and Communication in Contemporary Marathi Theater: A Sociolinguistic Perspective. India: Linguistic Society of India, 1992. Apte, Mahadev L. "Parody and Comment: Comedy in Contemporary Marathi Theater." The World and I (June, 1992): 671-681. Auden, W. H. " Notes on the Comic." Comedy: Meaning and Form. Ed. Robert W. Corrigan, San Francisco, CA: Chandler, 1965, 61-72. Baddely-Clinton, V. C. The Burlesque Tradition in the English Theatre after 1660. 1952. Balordi, A. Emma Sopena. "Dos Traducciones (Frances y Espanol) de Algunos Rasgos de Humor en La Locandiera. Carlo Goldoni: Una Vida Para El Teatro. Eds Inez Rodriguez Gomez, and Juli Leal Duart. Valencia, Spain: Universitat de Valencia Departament de Filologia Francesa i Italiana, 1996, 119-127. Barber, C. L. "The Saturnalian Pattern in Shakespeare's Comedy." Comedy: Meaning and Form. Ed. Robert W. Corrigan, San Francisco, CA: Chandler, 1965, 363-377. Baudelaire, Charles. "On the Essence of Laughter." Comedy: Meaning and Form. Ed. Robert W. Corrigan, San Francisco, CA: Chandler, 1965, 449=465. Belkin, Ahuva. "`Here's My Coxcomb': Some Notes on the Fool's Dress." Assaph: Studies in the Theatre 1.1 (1984): 40-54. Bentley, Eric. "Farce." Comedy: Meaning and Form. -

History of Greek Theatre

HISTORY OF GREEK THEATRE Several hundred years before the birth of Christ, a theatre flourished, which to you and I would seem strange, but, had it not been for this Grecian Theatre, we would not have our tradition-rich, living theatre today. The ancient Greek theatre marks the First Golden Age of Theatre. GREEK AMPHITHEATRE- carved from a hillside, and seating thousands, it faced a circle, called orchestra (acting area) marked out on the ground. In the center of the circle was an altar (thymele), on which a ritualistic goat was sacrificed (tragos- where the word tragedy comes from), signifying the start of the Dionysian festival. - across the circle from the audience was a changing house called a skene. From this comes our present day term, scene. This skene can also be used to represent a temple or home of a ruler. (sometime in the middle of the 5th century BC) DIONYSIAN FESTIVAL- (named after Dionysis, god of wine and fertility) This festival, held in the Spring, was a procession of singers and musicians performing a combination of worship and musical revue inside the circle. **Women were not allowed to act. Men played these parts wearing masks. **There was also no set scenery. A- In time, the tradition was refined as poets and other Greek states composed plays recounting the deeds of the gods or heroes. B- As the form and content of the drama became more elaborate, so did the physical theatre itself. 1- The skene grow in size- actors could change costumes and robes to assume new roles or indicate a change in the same character’s mood. -

Comedy of Manners

Compiled and designed by Milan Mondal, Assistant Professor in English, Narajole Raj College Background Reading Comedy of Manners ENGLISH(CC); SEM-II;PAPER-C3T; COMEDY OF MANNERS (BACKGROUND READING) Compiled and designed by Milan Mondal, Assistant Professor in English, Narajole Raj College Overview • A comedy of Manners is a play concerned with satirising the society’s manners. A manner is the method in which everyday duties are performed, conditions of society, or way of speaking. It implies a polite and well-bred behaviour. • The Comedy of manners, also called anti-sentimental comedy, is a form of comedy that satirizes the manners and affections of contemporary society and questions social standards. Social class stereotypes are often represented through stock characters(a stereotypical fictional person or type of person in a literary work). • A Comedy of Manners often sacrifices the plot, which usually centres on some scandal, to witty dialogues ans sharp social commentary . ENGLISH(CC); SEM-II;PAPER-C3T;RESTORATIION COMEDY OF MANNERS (BACKGROUND READING) Compiled and designed by Milan Mondal, Assistant Professor in English, Narajole Raj College • Satirizes the manners and affections of a social class • Often represented by stereotypical stock characters • Restoration Comedy is the highpoint of Comedy of Manners • It deals with the relations and intrigues of men and women living in sophisticated upper class society • It is light, deft and vivacious in tone • Unlike satire, Comedy of Manners tends to reward its cleverly unscrupulous characters rather than punish their immorality. • The plot of the comedy is often concerned with scandal • A middle-class reaction against the courtly Restoration comedy resulted in the sentimental comedy of the 18th Century . -

Stand-Up Comedy and Caste in India

IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 7 – Issue 1 – Summer 2020 Humour and the Margins: Stand-Up Comedy and Caste in India Madhavi Shivaprasad, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India Abstract Stand-up comedy as an art form has been known as one of the most powerful forms of expression to speak truth to power. In India, political satire as stand-up is highly popular. However, there is a serious gap in recognising and critiquing social hierarchies, particularly the Indian caste system. Most comedians, including the women who are known as strong critics of patriarchal structures within Indian society and the comedy industry in India, do not see the lack of representation of a Dalit voice in the industry as a structural problem. When caste is specifically named in the routines performed by them, all of them incidentally are a reference to their upper-caste identities in a non-ironical manner. Through critical discourse analysis, the article analyses stand-up comedy videos by these comedians online videos, as well as other non-humorous critiques they have offered on other platforms such as social media in order to understand the implications of these references. The article argues that these narratives reflect the general dominant caste discourse that the upper-caste comedians are a part of and also reconstitute the same by reiterating their own locations within the caste system. Finally it reflects on the significance of humour and particularly stand-up comedy to effect change. Recognising that humour and laughter are social activities also means to acknowledge that they hold potential to break existing stereotypes. -

UPSTATERS Comedy Show Flier

the Comedy Show UPSTATERS Former SUNY BROOME students and area locals are ready to showcase their comedic talents in an hour-long - virtual - comedy show. Coming off their successful comedy show last fall and featured on News Channel 34 -- COMEDIANS STUMBLING HOME players Wendy Wilkins (’89) and Damon Millard (’99) are joined by local Taury Seward and former upstater Catherine “POVs” Povinelli. WENDY WILKINS Originally from Vestal, NY, Wendy has performed all over California, the Mid West and New York. Her brash, blatantly truthful style is hilarious, captivating and delicious. Wendy regularly performs at the IMPROV, ICE HOUSE and FLAPPERS in Los Angeles and on the road, opens for Ian Bagg, Eddie Pepitone and Laura Hayden. This month, Wendy’s in the Burbank Comedy Festival, has been a finalist for the 2009 Funniest Female in So. Cal and won Uncle Clyde’s Comedy Competition in 1998. DAMON MILLARD Damon Millard is a sharp, thought provoking stand-up comic who mixes story-telling, quick wit, and bizarre observations of everyday situations into a laugh riot performance. Dripping with charisma he’s an unapologetic white-trash persona. Damon has two albums, “Shame, Pain, And Love” on the Comedy Dynamics label, and “Unicycle” released by Advanced Ham. Damon’s jokes are featured on SiriusXM, Laughs, and streaming digitally on Apple Music, Pandora, and Spotify. He’s spent the last 10 years zig-zagging the country playing all kinds of gigs. He has performed in the Milwaukee Comedy Festival, The Flyover Comedy Festival, The New York City Free Comedy Festival and many more. He hosts the Low-Budget Show and produces one of New York City’s best indy-comedy show, The Punching Bag. -

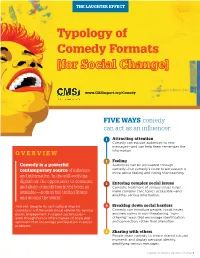

Typology of Comedy Formats

THE LAUGHTER EFFECT Typology of Comedy Formats www.CMSimpact.org/Comedy FIVE WAYS comedy can act as an influencer: 1 Attracting attention Comedy can expose audiences to new messages—and can help them remember the information. OVERVIEW 2 Feeling Comedy is a powerful Audiences can be persuaded through comedy—but comedy’s route to persuasion is contemporary source of influence more about feeling and caring than learning. and information. In the still-evolving digital era, the opportunity to consume 3 Entering complex social issues and share comedy has never been as Comedic treatment of serious issues helps available—both in the United States make complex civic topics accessible—and amplifies serious information. and around the world. And yet, despite its vast cultural imprint, 4 Breaking down social barriers comedy is a little-understood vehicle for serious Comedy can introduce people, social issues public engagement in urgent social issues— and new norms in non-threatening, “non- even though humor offers frames of hope and othering” ways that encourage identification optimism that encourage participation in social and connection, rather than alienation. problems. 5 Sharing with others People share comedy to create shared cultural moments and display personal identity, amplifying serious messages. Typology of Comedy [for Social Change] 1 THE LAUGHTER EFFECT Typology Of Comedy Formats From satirical faux news programs to comedic public service announcements, mediated comedy that deals with complex social and civic issues is produced, distributed and experienced in distinctive ways. Across available research about mediated comedy’s intersection with social issues—on the route to social change—four primary comedy formats are vital. -

Class, Language, and American Film Comedy

CLASS, LANGUAGE, AND AMERICAN FILM COMEDY CHRISTOPHER BEACH The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Christopher Beach 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Adobe Garamond 11/14 pt. System QuarkXPress [] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beach, Christopher. Class, language, and American film comedy / Christopher Beach. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0521 80749 2 – ISBN 0 521 00209 (pb.) 1. Comedy films – United States – History and criticism. 2. Speech and social status – United States. I. Title. PN1995.9.C55 B43 2001 791.43 617 – dc21 2001025935 ISBN 0 521 80749 2 hardback ISBN 0 521 00209 5 paperback CONTENTS Acknowledgments page vii Introduction 1 1 A Troubled Paradise: Utopia and Transgression in Comedies of the Early 1930s 17 2 Working Ladies and Forgotten Men: Class Divisions in Romantic Comedy, 1934–1937 47 3 “The Split-Pea