Sitcom Humour As Ventriloquism Thomas C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matthew Rolston.Pages

!1 Talking Heads "by Matthew Rolston If masks are, as Spanish philosopher and poet George Santayana wrote in the early 1920s, “arrested expressions and admirable echoes of feeling” then the Vent Haven Museum in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, must contain one of the world’s more unique and evocative collections. It is a place like no other. After discovering Vent Haven through an article by Edward Rothstein that appeared in the New York Times in June 2009, I became deeply intrigued by its inhabitants. I knew nothing of ventriloquism then, and still know very little, but I have learned of the poetry of these figures and the ways in which they were brought to life as an expression of their creators— the figure-makers and ventriloquists. " I began by approaching my subjects because of how they look, not necessarily because of their historic or cultural value.The faces that spoke to me most had expressions that I found enigmatic, pleading, Sphinx-like, hilarious, and disturbing—all at once. To me, the greatest portraits are mostly about finding a connection with the subject’s eyes. There’s an expression of yearning and desire in these eyes that I find disturbing. Matthew Rolston, Joe Flip, from the series “Talking Heads.” !2 Ventriloquism has ancient roots. Long before the music hall era, before vaudeville, radio, or television even existed, there was shamanism and there was ritual. When the shaman spoke to the tribe, channeling the voices of spirits—sometimes animist, sometimes divine —no doubt he or she used the same techniques as those used by modern ventriloquists. -

Middle Comedy: Not Only Mythology and Food

Acta Ant. Hung. 56, 2016, 421–433 DOI: 10.1556/068.2016.56.4.2 VIRGINIA MASTELLARI MIDDLE COMEDY: NOT ONLY MYTHOLOGY AND FOOD View metadata, citation and similar papersTHE at core.ac.ukPOLITICAL AND CONTEMPORARY DIMENSION brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Summary: The disappearance of the political and contemporary dimension in the production after Aris- tophanes is a false belief that has been shared for a long time, together with the assumption that Middle Comedy – the transitional period between archaia and nea – was only about mythological burlesque and food. The misleading idea has surely risen because of the main source of the comic fragments: Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters. However, the contemporary and political aspect emerges again in the 4th c. BC in the creations of a small group of dramatists, among whom Timocles, Mnesimachus and Heniochus stand out (significantly, most of them are concentrated in the time of the Macedonian expansion). Firstly Timocles, in whose fragments the personal mockery, the onomasti komodein, is still present and sharp, often against contemporary political leaders (cf. frr. 17, 19, 27 K.–A.). Then, Mnesimachus (Φίλιππος, frr. 7–10 K.–A.) and Heniochus (fr. 5 K.–A.), who show an anti- and a pro-Macedonian attitude, respec- tively. The present paper analyses the use of the political and contemporary element in Middle Comedy and the main differences between the poets named and Aristophanes, trying to sketch the evolution of the genre, the points of contact and the new tendencies. Key words: Middle Comedy, Politics, Onomasti komodein For many years, what is known as the “food fallacy”1 has been widespread among scholars of Comedy. -

SATIRE, COMEDY and MENTAL HEALTH Coping with the Limits of Critique

SATIRE, COMEDY AND MENTAL HEALTH This page intentionally left blank SATIRE, COMEDY AND MENTAL HEALTH Coping with the Limits of Critique DIETER DECLERCQ University of Kent, UK United Kingdom – North America – Japan – India Malaysia – China Emerald Publishing Limited Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley BD16 1WA, UK First edition 2021 © 2021 Dieter Declercq. Published under an exclusive licence by Emerald Publishing Limited. Reprints and permissions service Contact: [email protected] No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. No responsibility is accepted for the accuracy of information contained in the text, illustrations or advertisements. The opinions expressed in these chapters are not necessarily those of the Author or the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-83909-667-9 (Print) ISBN: 978-1-83909-666-2 (Online) ISBN: 978-1-83909-668-6 (Epub) For my parents and Georgia. This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS About the Author ix Acknowledgements xi Abstract xiii Introduction 1 Aims 1 Method 3 Chapter outline 7 1. What Is Satire? 9 Introduction 9 Variety 9 Genre 10 Critique 13 Entertainment 17 Ambiguity 21 Conclusion 24 2. Satire as Therapy: Curing a Sick World? 25 Introduction 25 Heroic therapy 25 Political impact 28 Satire as magic 30 Satire and Trump 32 Journalism 37 Conclusion 39 3. -

Stand-Up Comedy and the Clash of Gendered Cultural Norms

Stand-up Comedy and the Clash of Gendered Cultural Norms The Honors Program Honors Thesis Student’s Name: Marlee O’Keefe Faculty Advisor: Amber Day April 2019 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 1 LITERATURE REVIEW.......................................................................................................... 2 COMEDY THEORY LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................. 2 GENDER THEORY LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................... 7 GENDERED CULTURAL NORMS ...................................................................................... 13 COMEDY THEORY BACKGROUND ................................................................................. 13 COMEDIANS ......................................................................................................................... 16 STEREOTYPES ..................................................................................................................... 20 STAND-UP SPECIALS/TYPES OF JOKES ......................................................................... 25 ROLE REVERSAL ............................................................................................................. 25 SARCASAM ....................................................................................................................... 27 CULTURAL COMPARISON: EXPECTATION VERSUS REALITY ........................... -

Stand-Up Comedy in Theory, Or, Abjection in America John Limon 6030 Limon / STAND up COMEDY / Sheet 1 of 160

Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America John Limon Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 1 of 160 Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 2 of 160 New Americanists A series edited by Donald E. Pease Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 3 of 160 John Limon Duke University Press Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America Durham and London 2000 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 4 of 160 The chapter ‘‘Analytic of the Ridiculous’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in Raritan: A Quarterly Review 14, no. 3 (winter 1997). The chapter ‘‘Journey to the End of the Night’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in Jx: A Journal in Culture and Criticism 1, no. 1 (autumn 1996). The chapter ‘‘Nectarines’’ is based on an essay that first appeared in the Yale Journal of Criticism 10, no. 1 (spring 1997). © 2000 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ! Typeset in Melior by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Tseng 2000.4.3 18:27 6030 Limon / STAND UP COMEDY / sheet 5 of 160 Contents Introduction. Approximations, Apologies, Acknowledgments 1 1. Inrage: A Lenny Bruce Joke and the Topography of Stand-Up 11 2. Nectarines: Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks 28 3. -

Monstrous Aunties: the Rabelaisian Older Asian Woman in British Cinema and Television Comedy

Monstrous Aunties: The Rabelaisian older Asian woman in British cinema and television comedy Estella Tincknell, University of the West of England Introduction Representations of older women of South Asian heritage in British cinema and television are limited in number and frequently confined to non-prestigious genres such as soap opera. Too often, such depictions do little more than reiterate familiar stereotypes of the subordinate ‘Asian wife’ or stage the discursive tensions around female submission and male tyranny supposedly characteristic of subcontinent identities. Such marginalisation is compounded in the relative neglect of screen representations of Asian identities generally, and of female and older Asian experiences specifically, within the fields of Film and Media analysis. These representations have only recently begun to be explored in more nuanced ways that acknowledge the complexity of colonial and post-colonial discoursesi. The decoupling of the relationship between Asian and Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi heritage, together with the foregrounding of religious rather than national-colonial identities, has further rendered the topic more complex. Yet there is an exception to this tendency. In the 1990s, British comedy films and TV shows began to carve out a space in which transgressive representations of aging Asian women appeared. From the subversively mischievous Pushpa (Zohra Segal) in Gurinder Chadha’s debut feature, Bhaji on the Beach (1993), to the bickering ‘competitive mothers’ of the ground-breaking sketch show, Goodness, Gracious Me (BBC 1998 – 2001, 2015), together 1 with the sexually-fixated grandmother, Ummi (Meera Syal), in The Kumars at Number 42 (BBC, 2001-6; Sky, 2014), a range of comic older female figures have overturned conventional discourses. -

Laughing at Power, Fascism, and Authoritarianism: Satire, Humor, Irony, and Interrogating Their Political Efficacy

Laughing at Power, Fascism, and Authoritarianism: Satire, Humor, Irony, and Interrogating Their Political Efficacy April 8-10, 2018 Center for Jewish History New York City Abstract deadline: September 1, 2017 Response by: October 1, 2017 Projects to be workshopped deadline: March 1, 2018 Satire, humor, and irony have served as powerful weapons against totalitarianism and other forms of authoritarianism and authoritarian leaders. Before Hitler was scary, he was considered a joke, someone to be laughed at. During World War II, journalists, artists, writers and film-makers around the globe, used their golden pens, cameras, and paintbrushes to create powerful weapons against fascism. Some of them lived in the relative safety of United States or China, others were in the midst of it all, in Polish ghettos, occupied parts of the Soviet Union, or hiding in French villages. Today we understand these works both as effective forms of resistance and powerful means of making sense of the incomprehensive historical events. Studying satirical films, cabarets, comedy routines, music, cartoons, caricatures, and jokes as historical sources reveals details of the zeitgeist of the time, simply unavailable from other sources. At the same time, humor is limited in its ability to effect politics. While someone could laugh at Hitler, Hitler could not be stopped only through laughter. The workshop, jointly hosted by the journal East European Jewish Affairs and the Center for Jewish History and sponsored by the University of Colorado’s Singer Fund for Jewish Studies, proposes a new way of thinking about humor and resistance by bringing together scholars, artists, musicians, and comedians, and use both scholarly methods of textual analysis and artistic imagination to work on uncovering how fascism was fought not with the sword, but with laughter, satire, and irony and a healthy dose of political organizing. -

Comedy of Manners

Compiled and designed by Milan Mondal, Assistant Professor in English, Narajole Raj College Background Reading Comedy of Manners ENGLISH(CC); SEM-II;PAPER-C3T; COMEDY OF MANNERS (BACKGROUND READING) Compiled and designed by Milan Mondal, Assistant Professor in English, Narajole Raj College Overview • A comedy of Manners is a play concerned with satirising the society’s manners. A manner is the method in which everyday duties are performed, conditions of society, or way of speaking. It implies a polite and well-bred behaviour. • The Comedy of manners, also called anti-sentimental comedy, is a form of comedy that satirizes the manners and affections of contemporary society and questions social standards. Social class stereotypes are often represented through stock characters(a stereotypical fictional person or type of person in a literary work). • A Comedy of Manners often sacrifices the plot, which usually centres on some scandal, to witty dialogues ans sharp social commentary . ENGLISH(CC); SEM-II;PAPER-C3T;RESTORATIION COMEDY OF MANNERS (BACKGROUND READING) Compiled and designed by Milan Mondal, Assistant Professor in English, Narajole Raj College • Satirizes the manners and affections of a social class • Often represented by stereotypical stock characters • Restoration Comedy is the highpoint of Comedy of Manners • It deals with the relations and intrigues of men and women living in sophisticated upper class society • It is light, deft and vivacious in tone • Unlike satire, Comedy of Manners tends to reward its cleverly unscrupulous characters rather than punish their immorality. • The plot of the comedy is often concerned with scandal • A middle-class reaction against the courtly Restoration comedy resulted in the sentimental comedy of the 18th Century . -

Introduction in FOCUS: Revoicing the Screen

IN FOCUS: Revoicing the Screen Introduction by TESSA DWYER and JENNIFER o’mEARA, editors he paradoxes engendered by voice on-screen are manifold. Screen voices both leverage and disrupt associations with agency, presence, immediacy, and intimacy. Concurrently, they institute artifice and distance, otherness and uncanniness. Screen voices are always, to an extent, disembodied, partial, and Tunstable, their technological mediation facilitating manipulation, remix, and even subterfuge. The audiovisual nature of screen media places voice in relation to— yet separate from—the image, creating gaps and connections between different sensory modes, techniques, and technologies, allowing for further disjunction and mismatch. These elusive dynamics of screen voices—whether on-screen or off-screen, in dialogue or voice-over, as soundtrack or audioscape— have already been much commented on and theorized by such no- tables as Rick Altman, Michel Chion, Rey Chow, Mary Ann Doane, Kaja Silverman, and Mikhail Yampolsky, among others.1 Focusing primarily on cinema, these scholars have made seminal contribu- tions to the very ways that film and screen media are conceptual- ized through their focus on voice, voice recording and mixing, and postsynchronization as fundamental filmmaking processes. Altman 1 Rick Altman, “Moving Lips: Cinema as Ventriloquism,” Yale French Studies 60 (1980): 67–79; Rick Altman, Silent Film Sound (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004); Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia Univer- sity -

UPSTATERS Comedy Show Flier

the Comedy Show UPSTATERS Former SUNY BROOME students and area locals are ready to showcase their comedic talents in an hour-long - virtual - comedy show. Coming off their successful comedy show last fall and featured on News Channel 34 -- COMEDIANS STUMBLING HOME players Wendy Wilkins (’89) and Damon Millard (’99) are joined by local Taury Seward and former upstater Catherine “POVs” Povinelli. WENDY WILKINS Originally from Vestal, NY, Wendy has performed all over California, the Mid West and New York. Her brash, blatantly truthful style is hilarious, captivating and delicious. Wendy regularly performs at the IMPROV, ICE HOUSE and FLAPPERS in Los Angeles and on the road, opens for Ian Bagg, Eddie Pepitone and Laura Hayden. This month, Wendy’s in the Burbank Comedy Festival, has been a finalist for the 2009 Funniest Female in So. Cal and won Uncle Clyde’s Comedy Competition in 1998. DAMON MILLARD Damon Millard is a sharp, thought provoking stand-up comic who mixes story-telling, quick wit, and bizarre observations of everyday situations into a laugh riot performance. Dripping with charisma he’s an unapologetic white-trash persona. Damon has two albums, “Shame, Pain, And Love” on the Comedy Dynamics label, and “Unicycle” released by Advanced Ham. Damon’s jokes are featured on SiriusXM, Laughs, and streaming digitally on Apple Music, Pandora, and Spotify. He’s spent the last 10 years zig-zagging the country playing all kinds of gigs. He has performed in the Milwaukee Comedy Festival, The Flyover Comedy Festival, The New York City Free Comedy Festival and many more. He hosts the Low-Budget Show and produces one of New York City’s best indy-comedy show, The Punching Bag. -

(Museum of Ventriloquial Objects): Reconfiguring Voice Agency in the Liminality of the Verbal and the Vocal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery MUVE (Museum of Ventriloquial Objects) Reconfiguring Voice Agency in the Liminality of the Verbal and the Vocal Laura Malacart UCL PhD in Fine Art I, Laura Malacart confirm that the work presented in the thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Laura Malacart ABSTRACT MUVE (Museum of Ventriloquial Objects) Reconfiguring Voice Agency in the Liminality of the Verbal and the Vocal This project aims at reconfiguring power and agency in voice representation using the metaphor of ventriloquism. The analysis departs from ‘ventriloquial objects’, mostly moving image, housed in a fictional museum, MUVE. The museum’s architecture is metaphoric and reflects a critical approach couched in liminality. A ‘pseudo-fictional’ voice precedes and complements the ‘theoretical’ voice in the main body of work. After the Fiction, an introductory chapter defines the specific role that the trope of ventriloquism is going to fulfill in context. If the voice is already defined by liminality, between inside and outside the body, equally, a liminal trajectory can be found in the functional distinction between the verbal (emphasis on a semantic message) and the vocal (emphasis on sonorous properties) in the utterance. This liminal trajectory is harnessed along three specific moments corresponding to the three main chapters. They also represent the themes that define the museum rooms journeyed by the fictional visitor. Her encounters with the objects provide a context for the analysis and my practice is fully integrated in the analysis with two films (Voicings, Mi Piace). -

David Pendleton

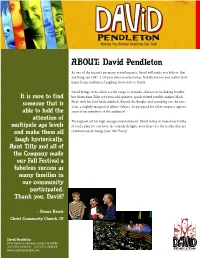

ABOUT: David Pendleton As one of the nation’s premiere ventriloquists, David will make you believe that anything can talk! A 20-year veteran entertainer, David’s humor and stellar tech- nique keeps audiences laughing from start to finish. David brings to his show a wide range of comedic characters including lovable, It is rare to find but blunt Aunt Tilly, a 94 year-old spinster; quick-witted trouble-maker, Mack someone that is Elroy with his laid-back sidekick; Buford the Beagle; and rounding out the cast, Vern, a slightly misguided albino Vulture. Be prepared for a few surprise appear- able to hold the ances from members of the audience! attention of Throughout all his high-energy entertainment, David mixes in humorous truths multipule age levels of God’s plan for our lives. As comedy delights your heart, let the truths that are and make them all communicated change your life! Enjoy! laugh hysterically. Aunt Tilly and all of the Company made our Fall Festival a fabulous success as many families in our community participated. Thank you, David! - Donna Harris Christ Community Church, IN David Pendleton 8750 Harrison Parkway, Fishers IN 46038 [317] 915-0192 PH [317] 571-2078 FX www.anythingcantalk.com - Dave & Charile, 1970 HOW I GOT STARTED A lot of people ask me how I got started in ventriloquism. Actually, my story is not unlike many of the professional ventriloquists that I know working in the business today. I was fascinated by puppets of all kinds as a youngster and loved television shows that featured them.