2019, Volume 28, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Practitioner Bibliography

Buddhist Practitioner Bibliography 1) Lineage a) The Awakened One: A Life of the Buddha. Sherab Chödzin. (Boulder CO: Shambhala Publications, 2009) b) The Great Kagyu Masters: The Golden Lineage Treasury. Khenpo Könchog Gyaltsen. ed. Victoria Huckenphaler (Ithaca New York: Snow Lion Publications, 1990) 2) Sutras a) Dhammapada: The Path of Perfection. trans. Juan Mascaró (Baltimore MD: Penguin Books Ltd., 1973) b) Early Buddhist Discourse. Ed. and trans. by John J. Holder (Indianapolis IN: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2006) c) The Holy Teaching of Vimalakirti: A Mahayana Scripture. Robert A. F. Thurman (Penn State University Press, 2003) 3) Philosophy a) Fundamentals: i) On the Four Noble Truths. Yeshe Gyamtso. (KTD Publications, 2013) b) Overview: i) The Essence of Buddhism: An Introduction to Its Philosophy and Practice. Traleg Kyabgon. (Boston MA: Shambala Publications, 2001) c) Abhidharma and Fundamentals: i) The Buddhist Psychology of Awakening: An In-depth Guide to Abhidharma. Steven D. Goodman (Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, 2020) ii) Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism. Reginald A. Ray. (Boston MA: Shambhala Publications Inc., 2000) d) Mahayana Systems: i) Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism. Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki. (London, UK: Luzac, 1907) ii) Living Yogācāra: An Introduction to Consciousness-Only Buddhism. Tagawa Shun’ei. trans. Charles Miller. (Somerville MA: Wisdom Publications, 2009) iii) Entry into the Inconceivable: An Introduction to Hua-Yen Buddhism. Thomas Cleary. e) Emptiness: i) Progressive Stages of Meditation on Emptiness: Experiential Training in Meditation Reflection and Insight. Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamsto Rinpoche. trans. Lama Shenpen Hookham. (UK: Shrimala Trust, 2016) ii) Introduction to Emptiness: As Taught in Tsong-kha-pa’s Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path. -

MBS Course Outline 11-12 (Updated on September 9, 11)

MBS Course Outline 11-12 (Updated on September 9, 11) Centre of Buddhist Studies The University of Hong Kong Master of Buddhist Studies Course Outline 2011-2012 (Course details laid out in this course outline is only for reference. Please refer to the version provided by the teachers in class for confirmation.) BSTC6079 Early Buddhism: a doctrinal exposition (Foundation Course) Lecturer Prof. Y. Karunadasa Tel: 2241-5019 Email: [email protected] Schedule: 1st Semester; Monday 6:30 – 9:30 p.m. Class Venue: P4, Chong Yuet Ming Physics Building Course Description This course will be mainly based on the early Buddhist discourses (Pali Suttas) and is designed to provide an insight into the fundamental doctrines of what is generally known as Early Buddhism. It will begin with a description of the religious and philosophical milieu in which Buddhism arose in order to show how the polarization of intellectual thought into spiritualist and materialist ideologies gave rise to Buddhism. The following themes will be an integral part of this study: analysis of the empiric individuality into khandha, ayatana, and dhatu; the three marks of sentient existence; doctrine of non-self and the problem of Over-Self; doctrine of dependent origination and its centrality to other Buddhist doctrines; diagnosis of the human condition and definition of suffering as conditioned experience; theory and practice of moral life; psychology and its relevance to Buddhism as a religion; undetermined questions and why were they left undetermined; epistemological standpoint and the Buddhist psychology of ideologies; Buddhism and the God-idea and the nature of Buddhism as a non-theistic religion; Nibbana as the Buddhist ideal of final emancipation. -

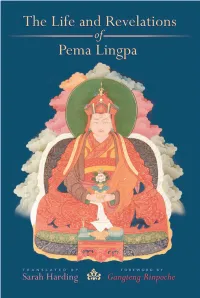

The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa Translated by Sarah Harding, Forward by Gangteng Rinpoche; Reviewed by D

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 26 Number 1 People and Environment: Conservation and Management of Natural Article 22 Resources across the Himalaya No. 1 & 2 2006 The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa translated by Sarah Harding, forward by Gangteng Rinpoche; reviewed by D. Phillip Stanley D. Phillip Stanley Naropa University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Stanley, D. Phillip. 2006. The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa translated by Sarah Harding, forward by Gangteng Rinpoche; reviewed by D. Phillip Stanley. HIMALAYA 26(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol26/iss1/22 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. of its large alluvial plains, extensive irrigation institutional integrity that they have managed to networks, and relatively egalitarian land-ownership negotiate with successive governments in Kangra patterns, like other Himalayan communities it is also to stay self-organized and independent, and to undergOing tremendous socio-economic changes get support from the state for the rehabilitation of due to the growing influence of the wider market damaged kuhls. economy. Kuhl regimes are experiencing declining Among the half dozen studies of farmer-managed interest in farming, decreasing participation, irrigation systems of the Himalaya, this book stands increased conflict, and the declining legitimacy out for its skillful integration of theory, historically of customary rules and authority structures. -

Eight Manifestations of Padmasambhava Essay

Mirrors of the Heart-Mind - Eight Manifestations of Padmasam... http://huntingtonarchive.osu.edu/Exhibitions/sama/Essays/AM9... Back to Exhibition Index Eight Manifestations of Padmasambhava (Image) Thangka, painting Cotton support with opaque mineral pigments in waterbased (collagen) binder exterior 27.5 x 49.75 inches interior 23.5 x 34.25 inches Ca. 19th century Folk tradition Museum #: 93.011 By Ariana P. Maki 2 June, 1998 Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, Padmakara, or Tsokey Dorje, was the guru predicted by the Buddha Shakyamuni to bring the Buddhist Dharma to Tibet. In the land of Uddiyana, King Indrabhuti had undergone many trials, including the loss of his young son and a widespread famine in his kingdom. The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara felt compassion for the king, and entreated the Buddha Amitabha, pictured directly above Padmasambhava, to help him. From his tongue, Amitabha emanated a light ray into the lake of Kosha, and a lotus grew, upon which sat an eight year old boy. The boy was taken into the kingdom of Uddiyana as the son of King Indrabhuti and named Padmasambhava, or Lotus Born One. Padmasambhava grew up to make realizations about the unsatisfactory nature of existence, which led to his renunciation of both kingdom and family in order to teach the Dharma to those entangled in samsara. Over the years, as he taught, other names were bestowed upon him in specific circumstances to represent his realization of a particular aspect of Buddhism. This thangka depicts Padmasambhava, in a form also called Tsokey Dorje, as a great guru and Buddha in the land of Tibet. -

MBS Course Outline 20-21 (Updated on August 13, 2020) 1

MBS Course Outline 20-21 (Updated on August 13, 2020) Centre of Buddhist Studies The University of Hong Kong Master of Buddhist Studies Course Outline 2020-2021 (Course details laid out in this course outline is only for reference. Please refer to the version provided by the teachers in class for confirmation.) Total Foundation Course Elective Course Capstone Programme requirements Credits (9 credits each) (6 credits each) experience Students admitted in 2019 or after 60 2 courses 5 courses 12 credits Students admitted in 2018 or before 63 2 courses 6 courses 9 credits Contents Part I Foundation Courses ....................................................................................... 2 BSTC6079 Early Buddhism: a doctrinal exposition .............................................. 2 BSTC6002 Mahayana Buddhism .......................................................................... 12 Part II Elective Courses .......................................................................................... 14 BSTC6006 Counselling and pastoral practice ...................................................... 14 BSTC6011 Buddhist mediation ............................................................................ 16 BSTC6012 Japanese Buddhism: history and doctrines ........................................ 19 BSTC6013 Buddhism in Tibetan contexts: history and doctrines ....................... 21 BSTC6032 History of Indian Buddhism: a general survey ................................. 27 BSTC6044 History of Chinese Buddhism ........................................................... -

Guru Padmasambhava and His Five Main Consorts Distinct Identity of Christianity and Islam

Journal of Acharaya Narendra Dev Research Institute l ISSN : 0976-3287 l Vol-27 (Jan 2019-Jun 2019) Guru Padmasambhava and his five main Consorts distinct identity of Christianity and Islam. According to them salvation is possible only if you accept the Guru Padmasambhava and his five main Consorts authority of their prophet and holy book. Conversely, Hinduism does not have a prophet or a holy book and does not claim that one can achieve self-realisation through only the Hindu way. Open-mindedness and simultaneous existence of various schools Heena Thakur*, Dr. Konchok Tashi** have been the hall mark of Indian thought. -------------Hindi----cultural ties with these countries. We are so influenced by western thought that we created religions where none existed. Today Abstract Hinduism, Buddhism and Jaininism are treated as Separate religions when they are actually different ways to achieve self-realisation. We need to disengage ourselves with the western world. We shall not let our culture to This work is based on the selected biographies of Guru Padmasambhava, a well known Indian Tantric stand like an accused in an alien court to be tried under alien law. We shall not compare ourselves point by point master who played a very important role in spreading Buddhism in Tibet and the Himalayan regions. He is with some western ideal, in order to feel either shame or pride ---we do not wish to have to prove to any one regarded as a Second Buddha in the Himalayan region, especially in Tibet. He was the one who revealed whether we are good or bad, civilised or savage (world ----- that we are ourselves is all we wish to feel it for all Vajrayana teachings to the world. -

The Mirror 77 November-December 2005

THE MIRROR Newspaper of the International Dzogchen Community November/December 2005 • Issue No. 77 Schedule Chögyal Namkhai Norbu 2006 2006 Jan. 27 - Feb. 5 Santi Maha Sangha Base Teaching and Practice Retreat Open Web Cast Margarita Gonpa during Tregchod Retreat & Web cast N ZEITZ Feb. 17 - 26 Longsal Saltong Lung teaching and Practice Retreat Restricted Web Cast Chögyal Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche March 10 -19 From the fifth volume of Longsal Retreat of Dzogchen Semlung Namkhache: Teaching and Practice Namkhache. THE UPADESHA ON THE TREGCHÖD Open Web Cast OF PRIMORDIAL PURITY RETREAT April 14 – 23 ka dag khregs chod kyi man ngag Tibetan Moxabustion Teaching and Application retreat May 5 -14 November 4 – 8 2005, Ati Lam-ngon Nasjyong A Retreat of Longsal teaching Preliminaries of the Path of Ati about Tashigar Norte, Margarita Island, Venezuela the Purification of the Six Lokas, Teaching and Practice. Open Web Cast by Agathe Steinhilber FRANCE e were about one hun- to sacrifice one’ s life, that life is Three Jewels, traditionally under- May 18 -22 dred-eighty nine stu- short and time is precious. stood as: 1. Taking refuge in the Paris Retreat dents, gathered in the Rinpoche expressed his delight Buddha and the teacher, 2. Taking Wbeautiful, airy Gonpa at Tashigar about the web cast. Thanks to refuge in the Dharma, the teach- May 26-28 Norte, attending the Longsal new technology , many people ings, and 3. Taking refuge in the Karmaling Retreat Tregchöd Retreat with Chögyal who otherwise do not have the Sangha, the spiritual community Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche. The possibility to attend the teachings of the fellow traveler , that sup - ITALY Gonpa was bustling with activity. -

Generate an Increasingly Nuanced Understanding of Its Teachings

H-Buddhism Sorensen on Labdrön, 'Machik's Complete Explanation: Clarifying the Meaning of Chöd: A Complete Explanation of Casting Out the Body as Food' Review published on Friday, September 1, 2006 Machig Labdrön. Machik's Complete Explanation: Clarifying the Meaning of Chöd: A Complete Explanation of Casting Out the Body as Food. Ithaca: Snow Lion, 2003. 365 pp. $29.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-55939-182-5. Reviewed by Michelle Sorensen (Center for Buddhist Studies, Columbia University Department of Religion) Published on H-Buddhism (September, 2006) An Offering of Chöd Machik Labdrön (Ma gcig Lab kyi sgron ma, ca. 1055-1153 C.E.) is revered by Tibetan Buddhists as an exemplary female philosopher-adept, a yogini, a dakini, and even as an embodiment of Prajñ?par?mit?, the Great Mother Perfection of Wisdom. Machik is primarily known for her role in developing and disseminating the "Chöd yul" teachings, one of the "Eight Chariots of the Practice Lineage" in Tibetan Buddhism.[1] Western interest in Chöd began with sensational representations of the practice as a macabre Tibetan Buddhist ritual in ethnographic travel narratives of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.[2] Such myopic representations have been ameliorated through later translations of Machik's biography and various ritual manuals, particularly those describing the "banquet offerings."[3] Since Western translators have privileged the genres of biographical and ritual texts, the richness of indigenous materials on Chöd (both in terms of quantity and quality) has been obscured.[4] This problem has been redressed by Sarah Harding's translation of Machik's Complete Explanation [Phung po gzan skyur gyi rnam bshad gcod kyi don gsal byed], one of the most comprehensive written texts extant within the Chöd tradition. -

Preparing-For-Ordination.Pdf

Preparing for Ordination: Reflections for Westerners Considering Monastic Ordination in the Western Buddhist Tradition Edited by Ven. Thubten Chodron Originally published by: Life as a Western Buddhist Nun For free distribution. Write to Sravasti Abbey, 692 Country Lane, Newport Wa 99156, USA. The decision to take monastic ordination is an important one, and to make it wisely, one needs information. In addition, one needs to reflect over a period of time on many diverse aspects of one's life, habits, aspirations, and expectations. The better prepared one is before ordaining, the easier the transition from lay to monastic life will be, and the more comfortable and joyous one will be as a monastic. This booklet, with articles by Asian and Western monastics, is designed to inform and to spark that reflection in non-Tibetans who are considering monastic ordination in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Thich Nhat Hanh's article and materials in this booklet have been edited and reprinted with his kind permission. Gendun Rinpoche's article first appeared in "Karme Gendun," the newsletter of Kundreul Ling, and has been reprinted here with his kind permission. This booklet as a whole is copyright by Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron. For permission to reprint the entire booklet, please contact her. For permission to reprint any of the articles separately, please contact the individual author. Addresses may be found with the biographies of the contributors. Contents Foreword His Holiness the Dalai Lama Introduction Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron The Benefits and Motivation for Monastic Ordination Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron and Bhikshuni Tenzin Kacho Being a Monastic in the West Bhikshu Thich Nhat Hanh If We Want to Work for the Good of All Beings, What Should We Do? Bhikshu Gendun Rinpoche H. -

Pema Lingpa.Pdf

Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page i The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page ii Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page iii The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa ሓ Translated by Sarah Harding Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york ✦ boulder, colorado Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page iv Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 www.snowlionpub.com Copyright © 2003 Sarah Harding All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. isbn 1-55939-194-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page v Contents Foreword by Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche vii Translator’s Preface ix Introduction by Holly Gayley 1 1. Flowers of Faith: A Short Clarification of the Story of the Incarnations of Pema Lingpa by the Eighth Sungtrul Rinpoche 29 2. Refined Gold: The Dialogue of Princess Pemasal and the Guru, from Lama Jewel Ocean 51 3. The Dialogue of Princess Trompa Gyen and the Guru, from Lama Jewel Ocean 87 4. The Dialogue of Master Namkhai Nyingpo and Princess Dorje Tso, from Lama Jewel Ocean 99 5. The Heart of the Matter: The Guru’s Red Instructions to Mutik Tsenpo, from Lama Jewel Ocean 115 6. A Strand of Jewels: The History and Summary of Lama Jewel Ocean 121 Appendix A: Incarnations of the Pema Lingpa Tradition 137 Appendix B: Contents of Pema Lingpa’s Collection of Treasures 142 Notes 145 Bibliography 175 Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page vi Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page vii Foreword by Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche his book is an important introduction to Buddhism and to the Tteachings of Guru Padmasambhava. -

Do Buddhists Pray?

Do Buddhists Pray? A panel discussion with Mark Unno, Rev. Shohaku Okumura, Sarah Harding and Bhante Madawala Seelawimala Sarah Harding is a Tibetan translator and lama in the Kagyü school of Vajrayana Buddhism and editor of Creation and Completion: Essential Points of Tantric Meditation (Wisdom). Rev. Shohaku Okumura is director of the Soto Zen Buddhism International Center in San Francisco. Mark Unno is ordained in the Shin Buddhist tradition and is an assistant professor of East Asian religions at the University of Oregon. The Venerable Wadawala Seelawimala is a Theravadin monk from Sri Lanka and professor at the Institute for Buddhist Studies and the Graduate Theological Seminary in Berkeley. Buddhadharma: Perhaps we could begin our discussion of the role of prayer in Buddhism by considering the Pure Land tradition, which is renowned for supplicating or invoking what it calls “other power.” Mark Unno: One of the primary practices of the Pure Land tradition is intoning the name of Amida Buddha. In the Shin school, we say Namu Amida Butsu, which roughly translates as “I take refuge in Amida Buddha,” or “I entrust myself to Amida Buddha.” Saying this name is understood as an act of taking refuge, or entrusting. This concept of entrusting, known in Japanese as shinjin, is widely regarded as a key to the Shin religious experience. Shinjin is often rendered in English as “true entrusting.” Understanding true entrusting can be helpful for understanding the nature of supplication or devotion in this tradition. On the one hand, shinjin means trusting oneself to the Buddha Amida, through saying the name. -

1 My Literature My Teachings Have Become Available in Your World As

My Literature My teachings have become available in your world as my treasure writings have been discovered and translated. Here are a few English works. Autobiographies: Mother of Knowledge,1983 Lady of the Lotus-Born, 1999 The Life and Visions of Yeshe Tsogyal: The Autobiography of the Great Wisdom Queen, 2017 My Treasure Writings: The Life and Liberation of Padmasambhava, 1978 The Lotus-Born: The Life Story of Padmasambhava, 1999 Treasures from Juniper Ridge: The Profound Instructions of Padmasambhava to the Dakini Yeshe Tsogyal, 2008 Dakini Teachings: Padmasambhava’s Advice to Yeshe Tsogyal, 1999 From the Depths of the Heart: Advice from Padmasambhava, 2004 Secondary Literature on the Enlightened Feminine and my Emanations: Women of Wisdom, Tsultrim Allione, 2000 Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism, Judith Simmer- Brown, 2001 Machik's Complete Explanation: Clarifying the Meaning of Chod, Sarah Harding, 2003 Women in Tibet, Janet Gyatso, 2005 Meeting the Great Bliss Queen: Buddhists, Feminists, and the Art of the Self, Anne Carolyn Klein, 1995 When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty: The Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet, Hildegard Diemberger, 2014 Love and Liberation: Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary Sera Khandro, Sarah Jacoby, 2015 1 Love Letters from Golok: A Tantric Couple in Modern Tibet, Holly Gayley, 2017 Inseparable cross Lifetimes: The Lives and Love Letters of the Tibetan Visionaries Namtrul Rinpoche and Khandro Tare Lhamo, Holly Gayley, 2019 A Few Meditation Liturgies: Yumkha Dechen Gyalmo, Queen of Great Bliss from the Longchen Nyingthik, Heart- Essence of the Infinite Expanse, Jigme Lingpa Khandro Thukthik, Dakini Heart Essence, Collected Works of Dudjom, volume MA, pgs.