Do Buddhists Pray?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Practitioner Bibliography

Buddhist Practitioner Bibliography 1) Lineage a) The Awakened One: A Life of the Buddha. Sherab Chödzin. (Boulder CO: Shambhala Publications, 2009) b) The Great Kagyu Masters: The Golden Lineage Treasury. Khenpo Könchog Gyaltsen. ed. Victoria Huckenphaler (Ithaca New York: Snow Lion Publications, 1990) 2) Sutras a) Dhammapada: The Path of Perfection. trans. Juan Mascaró (Baltimore MD: Penguin Books Ltd., 1973) b) Early Buddhist Discourse. Ed. and trans. by John J. Holder (Indianapolis IN: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2006) c) The Holy Teaching of Vimalakirti: A Mahayana Scripture. Robert A. F. Thurman (Penn State University Press, 2003) 3) Philosophy a) Fundamentals: i) On the Four Noble Truths. Yeshe Gyamtso. (KTD Publications, 2013) b) Overview: i) The Essence of Buddhism: An Introduction to Its Philosophy and Practice. Traleg Kyabgon. (Boston MA: Shambala Publications, 2001) c) Abhidharma and Fundamentals: i) The Buddhist Psychology of Awakening: An In-depth Guide to Abhidharma. Steven D. Goodman (Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, 2020) ii) Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism. Reginald A. Ray. (Boston MA: Shambhala Publications Inc., 2000) d) Mahayana Systems: i) Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism. Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki. (London, UK: Luzac, 1907) ii) Living Yogācāra: An Introduction to Consciousness-Only Buddhism. Tagawa Shun’ei. trans. Charles Miller. (Somerville MA: Wisdom Publications, 2009) iii) Entry into the Inconceivable: An Introduction to Hua-Yen Buddhism. Thomas Cleary. e) Emptiness: i) Progressive Stages of Meditation on Emptiness: Experiential Training in Meditation Reflection and Insight. Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamsto Rinpoche. trans. Lama Shenpen Hookham. (UK: Shrimala Trust, 2016) ii) Introduction to Emptiness: As Taught in Tsong-kha-pa’s Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path. -

MBS Course Outline 11-12 (Updated on September 9, 11)

MBS Course Outline 11-12 (Updated on September 9, 11) Centre of Buddhist Studies The University of Hong Kong Master of Buddhist Studies Course Outline 2011-2012 (Course details laid out in this course outline is only for reference. Please refer to the version provided by the teachers in class for confirmation.) BSTC6079 Early Buddhism: a doctrinal exposition (Foundation Course) Lecturer Prof. Y. Karunadasa Tel: 2241-5019 Email: [email protected] Schedule: 1st Semester; Monday 6:30 – 9:30 p.m. Class Venue: P4, Chong Yuet Ming Physics Building Course Description This course will be mainly based on the early Buddhist discourses (Pali Suttas) and is designed to provide an insight into the fundamental doctrines of what is generally known as Early Buddhism. It will begin with a description of the religious and philosophical milieu in which Buddhism arose in order to show how the polarization of intellectual thought into spiritualist and materialist ideologies gave rise to Buddhism. The following themes will be an integral part of this study: analysis of the empiric individuality into khandha, ayatana, and dhatu; the three marks of sentient existence; doctrine of non-self and the problem of Over-Self; doctrine of dependent origination and its centrality to other Buddhist doctrines; diagnosis of the human condition and definition of suffering as conditioned experience; theory and practice of moral life; psychology and its relevance to Buddhism as a religion; undetermined questions and why were they left undetermined; epistemological standpoint and the Buddhist psychology of ideologies; Buddhism and the God-idea and the nature of Buddhism as a non-theistic religion; Nibbana as the Buddhist ideal of final emancipation. -

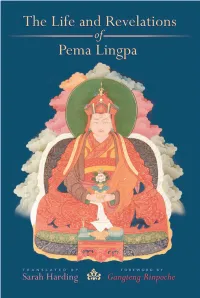

The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa Translated by Sarah Harding, Forward by Gangteng Rinpoche; Reviewed by D

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 26 Number 1 People and Environment: Conservation and Management of Natural Article 22 Resources across the Himalaya No. 1 & 2 2006 The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa translated by Sarah Harding, forward by Gangteng Rinpoche; reviewed by D. Phillip Stanley D. Phillip Stanley Naropa University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Stanley, D. Phillip. 2006. The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa translated by Sarah Harding, forward by Gangteng Rinpoche; reviewed by D. Phillip Stanley. HIMALAYA 26(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol26/iss1/22 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. of its large alluvial plains, extensive irrigation institutional integrity that they have managed to networks, and relatively egalitarian land-ownership negotiate with successive governments in Kangra patterns, like other Himalayan communities it is also to stay self-organized and independent, and to undergOing tremendous socio-economic changes get support from the state for the rehabilitation of due to the growing influence of the wider market damaged kuhls. economy. Kuhl regimes are experiencing declining Among the half dozen studies of farmer-managed interest in farming, decreasing participation, irrigation systems of the Himalaya, this book stands increased conflict, and the declining legitimacy out for its skillful integration of theory, historically of customary rules and authority structures. -

MBS Course Outline 20-21 (Updated on August 13, 2020) 1

MBS Course Outline 20-21 (Updated on August 13, 2020) Centre of Buddhist Studies The University of Hong Kong Master of Buddhist Studies Course Outline 2020-2021 (Course details laid out in this course outline is only for reference. Please refer to the version provided by the teachers in class for confirmation.) Total Foundation Course Elective Course Capstone Programme requirements Credits (9 credits each) (6 credits each) experience Students admitted in 2019 or after 60 2 courses 5 courses 12 credits Students admitted in 2018 or before 63 2 courses 6 courses 9 credits Contents Part I Foundation Courses ....................................................................................... 2 BSTC6079 Early Buddhism: a doctrinal exposition .............................................. 2 BSTC6002 Mahayana Buddhism .......................................................................... 12 Part II Elective Courses .......................................................................................... 14 BSTC6006 Counselling and pastoral practice ...................................................... 14 BSTC6011 Buddhist mediation ............................................................................ 16 BSTC6012 Japanese Buddhism: history and doctrines ........................................ 19 BSTC6013 Buddhism in Tibetan contexts: history and doctrines ....................... 21 BSTC6032 History of Indian Buddhism: a general survey ................................. 27 BSTC6044 History of Chinese Buddhism ........................................................... -

Generate an Increasingly Nuanced Understanding of Its Teachings

H-Buddhism Sorensen on Labdrön, 'Machik's Complete Explanation: Clarifying the Meaning of Chöd: A Complete Explanation of Casting Out the Body as Food' Review published on Friday, September 1, 2006 Machig Labdrön. Machik's Complete Explanation: Clarifying the Meaning of Chöd: A Complete Explanation of Casting Out the Body as Food. Ithaca: Snow Lion, 2003. 365 pp. $29.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-55939-182-5. Reviewed by Michelle Sorensen (Center for Buddhist Studies, Columbia University Department of Religion) Published on H-Buddhism (September, 2006) An Offering of Chöd Machik Labdrön (Ma gcig Lab kyi sgron ma, ca. 1055-1153 C.E.) is revered by Tibetan Buddhists as an exemplary female philosopher-adept, a yogini, a dakini, and even as an embodiment of Prajñ?par?mit?, the Great Mother Perfection of Wisdom. Machik is primarily known for her role in developing and disseminating the "Chöd yul" teachings, one of the "Eight Chariots of the Practice Lineage" in Tibetan Buddhism.[1] Western interest in Chöd began with sensational representations of the practice as a macabre Tibetan Buddhist ritual in ethnographic travel narratives of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.[2] Such myopic representations have been ameliorated through later translations of Machik's biography and various ritual manuals, particularly those describing the "banquet offerings."[3] Since Western translators have privileged the genres of biographical and ritual texts, the richness of indigenous materials on Chöd (both in terms of quantity and quality) has been obscured.[4] This problem has been redressed by Sarah Harding's translation of Machik's Complete Explanation [Phung po gzan skyur gyi rnam bshad gcod kyi don gsal byed], one of the most comprehensive written texts extant within the Chöd tradition. -

Pema Lingpa.Pdf

Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page i The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page ii Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page iii The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa ሓ Translated by Sarah Harding Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york ✦ boulder, colorado Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page iv Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 www.snowlionpub.com Copyright © 2003 Sarah Harding All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. isbn 1-55939-194-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page v Contents Foreword by Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche vii Translator’s Preface ix Introduction by Holly Gayley 1 1. Flowers of Faith: A Short Clarification of the Story of the Incarnations of Pema Lingpa by the Eighth Sungtrul Rinpoche 29 2. Refined Gold: The Dialogue of Princess Pemasal and the Guru, from Lama Jewel Ocean 51 3. The Dialogue of Princess Trompa Gyen and the Guru, from Lama Jewel Ocean 87 4. The Dialogue of Master Namkhai Nyingpo and Princess Dorje Tso, from Lama Jewel Ocean 99 5. The Heart of the Matter: The Guru’s Red Instructions to Mutik Tsenpo, from Lama Jewel Ocean 115 6. A Strand of Jewels: The History and Summary of Lama Jewel Ocean 121 Appendix A: Incarnations of the Pema Lingpa Tradition 137 Appendix B: Contents of Pema Lingpa’s Collection of Treasures 142 Notes 145 Bibliography 175 Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page vi Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page vii Foreword by Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche his book is an important introduction to Buddhism and to the Tteachings of Guru Padmasambhava. -

The Mirror 108 January-February 2011

No. 108 January, February 2011 Upcoming Retreats with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu Photo: M. Almici 2011 This is an approximate program subject to change Australia March 18–23 Namgyalgar Retreat Photo: G. Horner Singapore March 31–April 4 Singapore Retreat Taiwan Taipei Caloundra Retreat April 8–11 Taipei Teaching Retreat February 2011 Japan Pamela Oldmeadow April 15–19 Tokyo Teaching Retreat eople had gathered from all over As we sweltered in the heat and humid- joined in evening Chöd practices, as well The teaching is Australia from Perth to Cairns, and ity and cultivated compassion towards the as Xitro for a recently deceased Vajra broth- sPyod pa ro snyoms gyi man ngag Palso New Zealand, Japan, Europe large, lumbering, stinging march fl ies, our er, Steve. Russia and the Americas for this moment. We energy harmonized with the teachings and April 25–May 1 were so profoundly relieved, overjoyed an atmosphere of lightness and delight People browsed in the bookshop and ac- Moscow Retreat and grateful to see Rinpoche there ready to prevailed. quired thigle-colored t-shirts bearing the teach us. gold longsal symbol. They went kayaking May 2–6 Mornings saw Nicki Elliot teach the Dance on the dam, or swam in the patchily warm Kunsangar North Rinpoche talked to us over the next few of the Three Vajras under the supervi- and cool water. Some went to the beach. The teaching of Medicine Srothig, days about different paths, about vows and sion of Adriana Dal Borgo, and develop- Others played bagchen. Gentle enjoyment. the root terma text of initiation and guruyoga. -

Buddhist Nuns' Ordination in the Tibetan Canon

Buddhist Nuns’ Ordination in the Tibetan Canon Online Bibliography in Connection with the DFG Project compiled by Carola Roloff and Birte Plutat Part I: Author List February 2021 gefördert durch Gleichstellungsfonds des Asien-Afrika-Instituts der Universität Hamburg Nuns‘ Ordination in Buddhism – Bibliography. Part 1: Author / Title list February 2021 Abeysekara, Ananda (1999): Politics of Higher Ordination, Buddhist Monastic Identity, and Leadership in Sri Lanka. In Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 22 (2), pp. 255–280. Abeysekara, Ananda (2002): Colors of the Robe. Religion, Identity, and Difference. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. Adams, Vincanne; Dovchin, Dashima (2000): Women's Health in Tibetan Medicine and Tibet's "First" Female Doctor. In Ellison Banks Findly (Ed.): Women’s Buddhism, Buddhism’s Women. Tradition, Revision, Renewal. Boston: Wisdom Publications, pp. 433–450. Agrawala, V. S. (1966): Some Obscure Words in the Divyāvadāna. In Journal of the American Oriental Society 86 (2), pp. 67–75. Alatekara, Anata Sadāśiva; Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (Eds.) (1957): Felicitation Volume Presented to Professor Sripad Krishna Belvalkar. Banaras: Motilal Banarsidass. Ali, Daud (1998): Technologies of the Self. Courtly Artifice and Monastic Discipline in Early India. In Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (Journal d'Histoire Economique et Sociale de l'Orient) 41 (2), pp. 159–184. Ali, Daud (2000): From Nāyikā to Bhakta. A Genealogy of Female Subjectivity in Early Medieval India. In Julia Leslie, Mary McGee (Eds.): Invented Identities. The Interplay of Gender, Religion, and Politics in India. New Delhi, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 157–180. Ali, Daud (2003): Gardens in Early Indian Court Life. -

Heart of India

Heart of India Plus optional extensions in Bhutan: The Hidden Kingdom or The South of India: Kerala & Cochin or Kathmandu, Nepal 2016 Overseas Adventure Travel Heart of India Handbook Table of Contents 1. TRAVEL DOCUMENTS & ENTRY REQUIREMENTS ................................................................. 3 YOUR PASSPORT ....................................................................................................................................... 3 VISAS REQUIRED ...................................................................................................................................... 4 EMERGENCY PHOTOCOPIES ...................................................................................................................... 5 AIRPORT TRANSFERS ................................................................................................................................ 5 2. HEALTH ................................................................................................................................................. 6 IS THIS ADVENTURE RIGHT FOR YOU ? .................................................................................................... 6 STEPS TO TAKE BEFORE YOUR TRIP ........................................................................................................ 7 JET LAG PRECAUTIONS ............................................................................................................................. 8 STAYING HEALTHY ON YOUR TRIP ......................................................................................................... -

A Recent View of Tibet

■ V "5 ♦,* * * *■♦.♦ ♦••♦'•♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦♦' Bulk Rate m U.S. Postage Paid Ithaca, NY 14851 Permit No. 746 V Address Correction RequestedRequ SoNEWSLETTER AND CATALOG WINTER SUPPLEMENT 1995 Snow Lion Publications, PO Box 6483, Ithaca, NY 14851 607-273-8519 ISSN 1059-3691 Volume 10. Number 1 W News from the roof: A recent view of Tibet by Dr. Nick Ribush they are nowhere to be seen. More- helped make the right decision. over, Tibetan members of the Com- Finally, if even group discussion It's official: the Dalai Lama is an munist party or those simply em- didn't work, officials would "help" enemy of the people. Since Bill ployed by the Chinese are not al- them realize the truth. Freedom of Clinton reneged on all his promises lowed to display pictures of the thought, Chinese style. to care about Tibet, renewed MFN Dalai Lama in their homes. Worse, Why the big deal about pictures for China, and de-linked future they are not even allowed to main- of the Dalai Lama? Ask anyone trade considerations from human tain a Buddhist altar. Furthermore, who has been to Tibet. About the rights abuses, a brave new policy those who have sent their children only thing Tibetans ask foreign towards Tibet seems to have to India, which is the only place tourists for are pictures of His Ho- emerged. they can get a decent Tibetan edu- liness. And if you go to Tibet, they We are now witnessing the cation, have to bring them back to are the best thing you can bring. fourth Chinese view of Tibet's true Tibet soon, or they will never be To Tibetans in Tibet, pictures of the His Holiness. -

Introduction to Dzogchen

WISDOM ACADEMY Introduction to Dzogchen B. ALAN WALLACE Lesson 1: Introduction to Düdjom Lingpa and the Text Reading: Heart of the Great Perfection: Düdjom Lingpa’s Visions of the Great Perfection, Vol. 1 Introduction, pages 1–21 Wisdom Publications, Inc.—Not for Distribution Heart of the Great Perfection --9-- düdjom lingpa’s visions of the great perfection, volume 1 Foreword by Sogyal Rinpoche Translated by B. Alan Wallace Edited by Dion Blundell Wisdom Publications, Inc.—Not for Distribution Wisdom Publications 199 Elm Street Somerville, MA 02144 USA wisdompubs.org © 2016 B. Alan Wallace Foreword © 2016 Tertön Sogyal Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bdud-’joms-glin-pa, Gter-ston, 1835–1904. [Works. Selections. English] Düdjom Lingpa’s visions of the Great Perfection / Translated by B. Alan Wallace ; Edited by Dion Blundell. volumes cm Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: Volume 1. Heart of the Great Perfection — volume 2. Buddhahood without meditation — volume 3. TheV ajra essence. ISBN 1-61429-260-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Rdzogs-chen. I. Wallace, B. Alan. II. Title. BQ942.D777A25 2016 294.3’420423—dc23 2014048350 ISBN 978-1-61429-348-4 ebook ISBN 978-1-61429-236-4 First paperback edition 20 19 18 17 16 5 4 3 2 1 Cover and interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. -

Sages of the Ages: a Buddhist Bibliography

TOP HITS OF THE SAGES OF THE AGES A BUDDHIST BIBLIOGRAPHY A) OVERVIEW 1) An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings History and Practice. Peter Harvey. (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1990‐2012) 2) The Foundations of Buddhism. Rupert Gethin. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1998) 3) The Small Golden Key: To the Treasure of the Various Essential Necessities of General and Extraordinary Buddhist Dharma. Thinley Norbu, trans. Lisa Anderson. (Boston MA: Shambhala Publication Inc., 1977‐1993) 4) Buddhism as Philosophy: An Introduction. Mark Siderits. (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2007) 5) Engaging Buddhism: Why It Matters to Philosophy. Jay L. Garfield. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015) 6) Indestructible Truth: The Living Spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism. Reginald A. Ray. (Boston MA: Shambhala Publications Inc., 2000) 7) Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. Paul Williams. (New York, NY: Routledge, 1989‐2009) 8) On the Path to Enlightenment: Heart Advice from the Great Tibetan Masters. Matthieu Ricard (Boston MA: Shambhala Publications Inc., 2013) 9) Studies in Buddhist Philosophy. Mark Siderits. ed Jan Westerhoff. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016) 10) The Essence of Buddhism: An Introduction to Its Philosophy and Practice. Traleg Kyabgon. (Boston MA: Shambala Publications, 2001) 11) What Makes You Not a Buddhist? Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse. (Boston MA: Shambhala Publications Inc., 2007) 12) The Art of Awakening: A User’s Guide to Tibetan Buddhist Art and Practice. Konchog Lhadrepa and Charlotte Davis. (Boulder, CO: Snow Lion, 2017) B) HISTORY OR DEVELOPMENT OF DHARMA 1) A Concise History of Buddhism. Andrew Skilton. (Birmingham UK: Windhorse Publications, 1994) 2) Buddhism and Asian History: Religion, History, and Culture: Selections from The Encyclopedia of Religion.